(Thread) What is a computer? Definitions are contentious precisely because there is so much at stake (culturally, financially, infrastructurally) in the symbols and narratives we construct around the "computer".

Defining computers is a political act.

Defining computers is a political act.

Sometimes the computer is presented as the prototypical non-agent, confined to simple and brute deterministic operations over which it has no control. "Algorithmic" means "entirely predictable" and therefore devoid of the spark of creativity supposed to characterize humankind.

Other times, the computer is presented as an all-seeing, all-knowing data wizard, pulling obscure information from the ethercloud on demand. Or it& #39;s an economic panacea. Or it& #39;s a consumer gadget, something you can buy at a store and take home and give to your kid to play with.

The obvious conflict between these narratives is most clear in cases where that supposedly exclusive "human spark of creativity" is somehow replicated in our machines.

For those who see computers as nonagents, this possibility is an offense of the highest order.

For those who see computers as nonagents, this possibility is an offense of the highest order.

So these views squabble among themselves, each clinging to narratives from pessimistic and cynical to optimistic and utopic.

What these views share is the wish to fit the computer to some narrative trajectory of history: building to a climax or going down the tubes.

What these views share is the wish to fit the computer to some narrative trajectory of history: building to a climax or going down the tubes.

The centrist impulse is to find some reassuring middle ground: some form of cautious optimism, or perhaps the aesthetics of cyberpunk activism. But ultimately these are modes of avoiding the central challenge, which is to understand what the computer *is*.

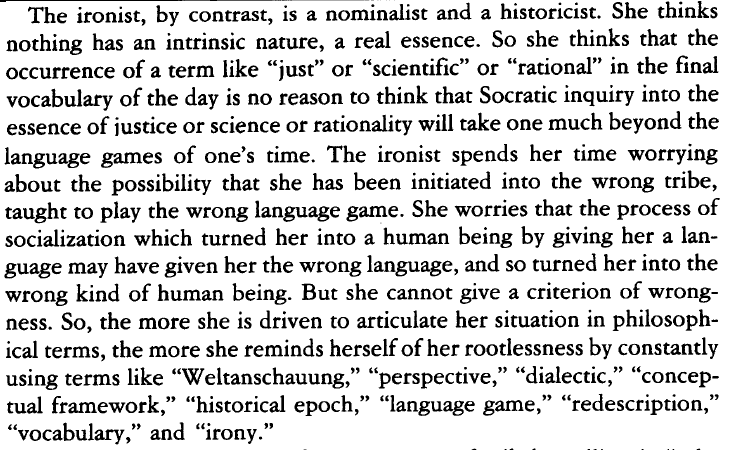

Rorty says we engage such questions in two ways: as a "metaphysician" who takes questions of intrinsic natures at face value, or as an "ironist" who rejects the idea of intrinsic natures entirely.

If we are to take the multifaceted politics of the computer seriously, then we must approach the question as an ironist, always worried about the language games we have adopted, always curious about the norms and practices available in alternative framings.

By offering a definition of a "computer" an ironist is not speaking as a metaphysican hoping to capture an absolute essence, the ultimate truth about computers.

Instead, the ironist is offering a potential language game that others might find useful for their own purposes.

Instead, the ironist is offering a potential language game that others might find useful for their own purposes.

An ironist might prefer not to define "computers" at all, lest the definition be mistaken for an essentialist metaphysical claim.

Even in computer science there are many different models of computation, each of which characterize "computers" in different ways.

Even in computer science there are many different models of computation, each of which characterize "computers" in different ways.

But at the heart of computer science is a universality claim, the Church-Turing thesis, which says that two models of computation (Turing& #39;s machines and the lambda calculus) are equivalent with each other and with any other model of effective computation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church%E2%80%93Turing_thesis">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chur...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church%E2%80%93Turing_thesis">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chur...

We don& #39;t have to adopt the computer scientist& #39;s jargon! But it& #39;s at least worth considering how they use the term, and what benefits it might have.

The universality of the Church-Turing thesis implies that we can talk about "computation" independent of specific computing models.

The universality of the Church-Turing thesis implies that we can talk about "computation" independent of specific computing models.

At least for the computer scientist, the fact of different models of computation is not a barrier to the study of computation abstractly.

Note a subtle shift to thinking about "computation", an abstract process, rather than "a computer", a definite object.

Note a subtle shift to thinking about "computation", an abstract process, rather than "a computer", a definite object.

We can (and should, and will!) continue thinking about computation. But this threatens to distract us from our goal of defining a computer, until we have some clarity on how things (like computers) relate to processes (like computation).

Is anything that computes a computer?

Is anything that computes a computer?

Here the ironist can finally say something substantive and useful, for they can encourage us to treat terms like "computer" and "computation" as an *interpretive stance* we take towards certain systems, in order to explain, predict, and model their behavior.

For the ironist, nothing "is" a computer essentially because nothing has such essences.

Nevertheless it can be useful (scientifically, narratively, politically) to treat certain systems as computers. What does that mean? It means to treat their processes as computations.

Nevertheless it can be useful (scientifically, narratively, politically) to treat certain systems as computers. What does that mean? It means to treat their processes as computations.

Lest this be read as vacuously circular, it will be useful to give a specific model of computation (which again, computer scientists assure us are formally equivalent).

I like thinking about computations as operations of an abstract state machine.

I like thinking about computations as operations of an abstract state machine.

Imagine a system with a set of states, and which moves from one state to the next (an "operation") in regular ways. This is *almost* a sufficient model of computation. All it needs is "memory": the capacity to bring information from previous states into the next state.

It takes a little more work to make this rigorous, but that& #39;s really all you need for computation: a state machine with memory. From this perspective, any system that can be described as a state machine with memory can be described as a computer.

It& #39;s worth pausing here to consider how many different kinds of things can be described as a state machine with memory. You& #39;d be hard-pressed to think of some system that cannot be described in this way.

This definition does not restrict the discussion to laptops and cell phones. For instance, an elevator that remembers which direction it is going can be described as a "computer" on this definition. Each move between floors is a "computation".

To say that "the elevator is a computer" is just to say that we can model its relevant behavior as a state machine with memory. This abstract machine doesn& #39;t capture everything about some physical elevator, but it captures something important about how it operates.

Q: Does that mean everything is a computer? Water can change state from liquid to ice. Is that a computation?

A: Well, maybe! Just because we can describe a process in some way doesn& #39;t mean we should. What are we using the description for?

A: Well, maybe! Just because we can describe a process in some way doesn& #39;t mean we should. What are we using the description for?

There are reasons to treat phase changes in computational terms! There& #39;s a whole branch of materials science that looks at "phase change materials" and their applications to memory storage. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41578-018-0076-x">https://www.nature.com/articles/...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter