One of the most iconic First World War photographs - Ivor Castle’s & #39;Over the Top& #39; - turns 104 years old this month. Let’s explore the history of this extremely famous (yet misunderstood) photograph #thread #warphotos

(This #thread is derived from a talk I gave last year for Remembrance Day, but as we all know, this year looks a little different. Alas, the magic of the internet).

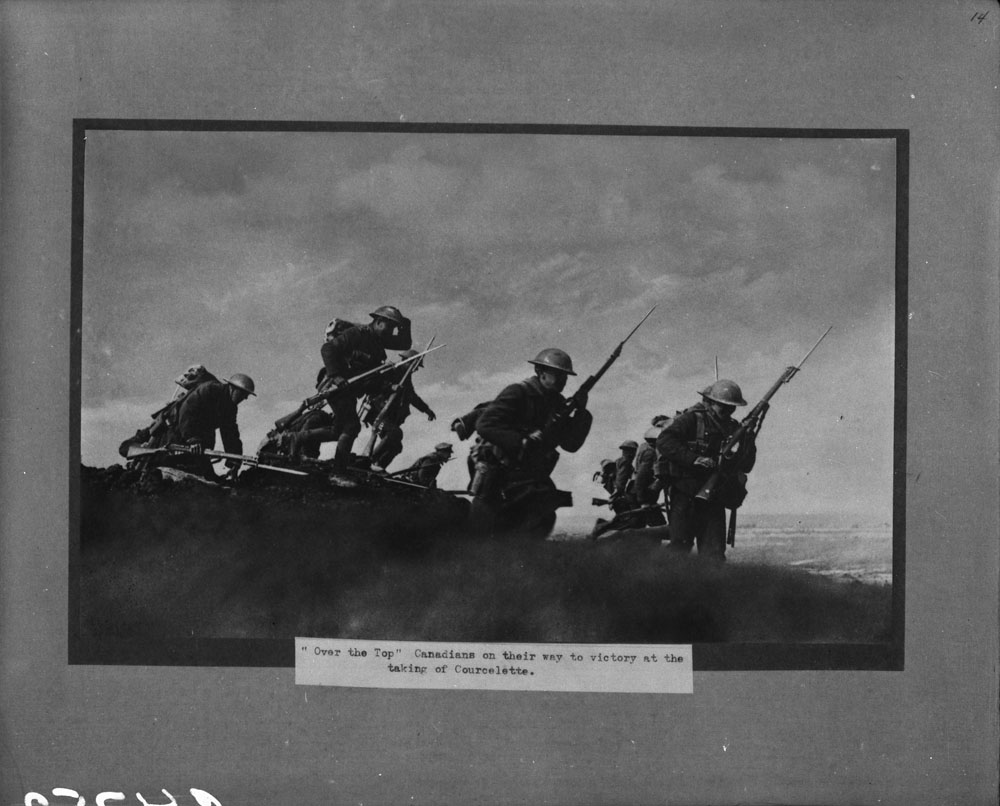

Over the Top, taken in October 1916, is actually a series of 4 photographs, and I’ve posted them all for you here (not sure why O-876, the final photograph in the series is digitized from a print, unlike O-873-875). These four belong to Library and Archives Canada.

O-874 is used most often (this is usually what I mean by “Over the Top,” but really the title (to me) stands for any of the 4 images). O-873 (soldiers fixing bayonets) gets its share of use too. These photos are on the cover of SEVERAL #FWW books, incl. on non-Canadian subjects.

What’s sometimes less known is the fact that although Over the Top was meant to portray soldiers going into action at Courcelette, the photographs were actually taken during training. Some items were cropped out (ie. a breech cover) and some shell bursts were added in.

You’ll still see one or two men wearing soft caps instead of helmets. And obviously to get photographs from this angle would put Castle’s back to the enemy. The position of the photographer tends to be a telltale sign for staged photographs.

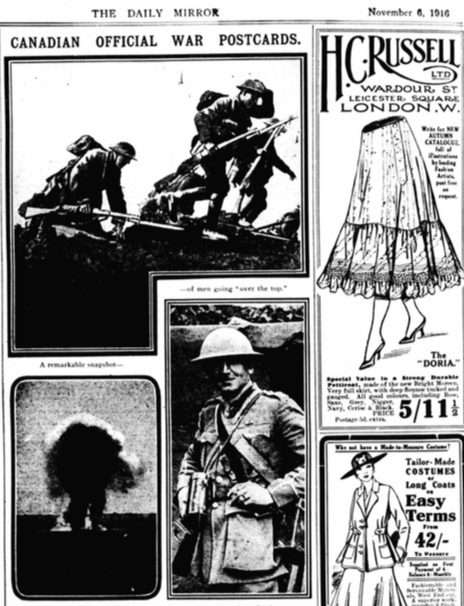

Over the Top was first published on the cover of the Daily Mirror on October 16, 1916 (this is a really poor reproduction, but you get the idea!)

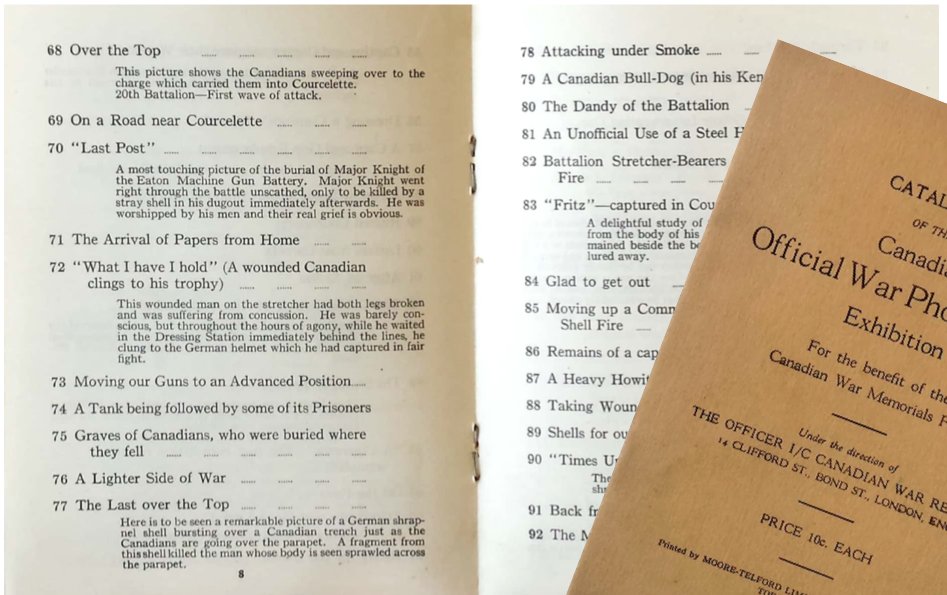

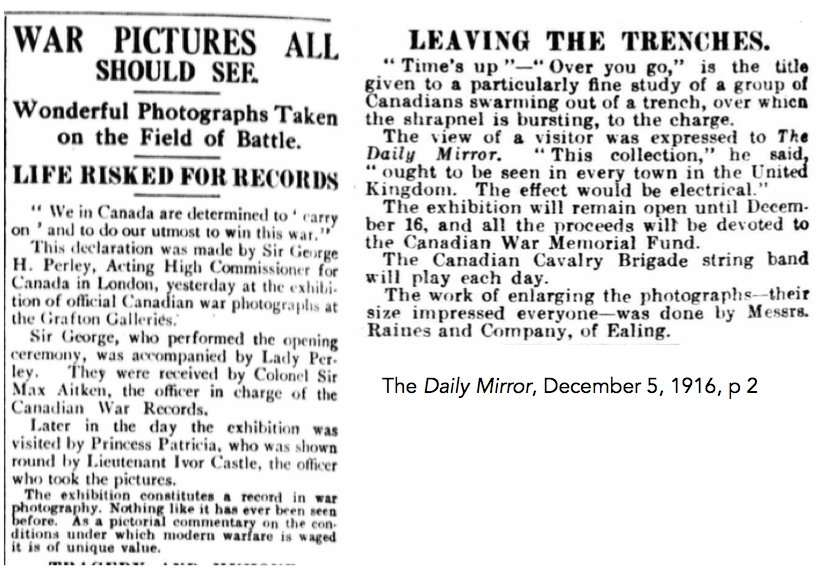

Over the Top was then put on exhibition in December 1916 at London’s Grafton Galleries. It was lauded in the press as an example of Castle’s bravado as Canada’s official war photographer.

Here is some press coverage of Over the Top, in the Daily Mirror and the Times, published in late 1916.

The photographs were also published in the Canadian War Pictorial, with a little handy editing. Funny enough, the number previous to this issue promised readers that the pages of the CWP would never show faked photographs  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙂" title="Leicht lächelndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Leicht lächelndes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙂" title="Leicht lächelndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Leicht lächelndes Gesicht">

In late 1916, as Over the Top brought Castle a good deal of notoriety, British official photog Ernest Brooks complained to the War Office that Castle had been faking.

Brooks was probably a little peeved that he had been asked not to fake photographs, when Castle’s boss Lord Beaverbrook gave him relatively free reign. Brooks had different rules to follow.

I’ve had a lot of people tell me that Castle was chastised for his fakery, but I’ve never found documentary evidence of this (so if you have anything solid, feel free to get in touch). The archival record tends to show the opposite.

The photographs continued to be published in 1917. This includes in the Glasgow Daily Record and the Daily Mirror - both accompanied other stories of Canadian battles, as though these 4 images could stand in for any fight.

Castle was also promoted from temporary Lieutenant to temporary Captain in February 1917 (ie. the opposite of getting a reprimand, he got a pat on the back).

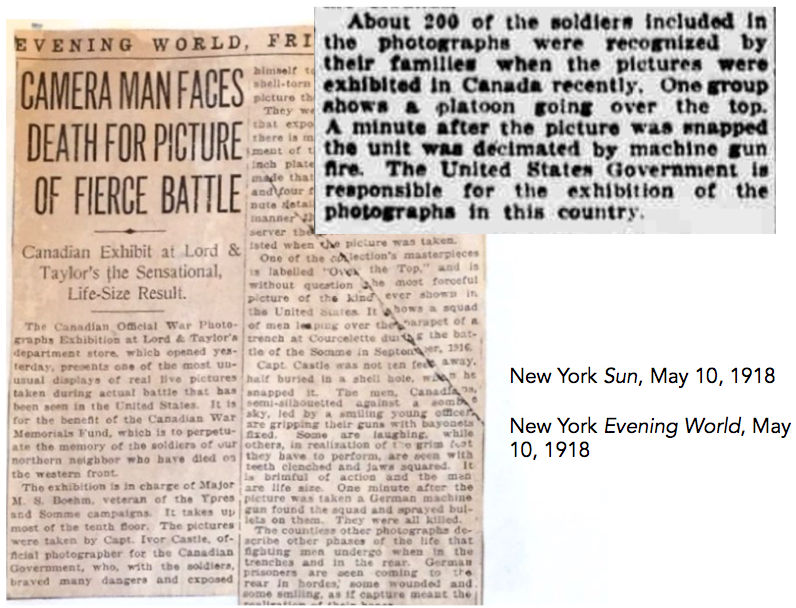

That December 1916 Grafton Galleries exhibition later travelled throughout North America. The press coverage of its arrival in New York shows us that the mythology around this “battle” photograph got pretty weird.

Not only were the photographs meant to show soldiers going into battle (ok), but now it included men just seconds before their deaths (um, what?). These photographs are fascinating because they represent one of the weird games of “telephone” that we see in FWW imagery.

So when did the myth begin to unravel? As far as I can tell, it wasn’t really until the 1970s that historians were a) talking about Canadian war photography at all, and B) talking about how Over the Top is a series of fakes.

This came about when Castle’s successor, William Rider-Rider, gave an interview with historian/archivist Peter Robertson. R-R says he wants to “set the record straight” (meaning in 1970s there was still a common misconception) about Over the Top.

This information was then picked up by subsequent historians: Jane Carmichael, Martyn Jolly, Laura Brandon, Hilary Roberts, Maureen Magerman, and yours truly. The myth continued to unravel as historians learned more about Castle’s other faked photographs.

Sound like a super dope subject? Don’t forget to keep an eye out for my forthcoming book on the subject, it’ll be out someday in the near-ish future.

And yet, Over the Top is STILL used to this day for online commemoration campaigns, book covers, getting tossed around social media without context, etc.

I’ve argued a lot that digging into a photographer’s entire wartime oeuvre is going to a) teach us more about that photographer’s approach and b) give us a richer corpus of imagery to draw upon. Let’s all do that, OK?

So, to conclude, Over the Top represents the gradual building of a myth, and the gradual unraveling. This is just one of the inherent possibilities that photography (an endlessly reproducible medium) presents to us. / fin Happy Canadian Thanksgiving, please wear your mask  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦃" title="Truthahn" aria-label="Emoji: Truthahn">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦃" title="Truthahn" aria-label="Emoji: Truthahn">

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="The photographs were also published in the Canadian War Pictorial, with a little handy editing. Funny enough, the number previous to this issue promised readers that the pages of the CWP would never show faked photographs https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙂" title="Leicht lächelndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Leicht lächelndes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="The photographs were also published in the Canadian War Pictorial, with a little handy editing. Funny enough, the number previous to this issue promised readers that the pages of the CWP would never show faked photographs https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙂" title="Leicht lächelndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Leicht lächelndes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>