The best aircraft names are of course those that tell you exactly what they& #39;re going to do.

Spitfire? Excellent!

Avenger? Yeah, let& #39;s go avenge!

Fireball? Sorry sir. Washing my hair that day, sir.

Spitfire? Excellent!

Avenger? Yeah, let& #39;s go avenge!

Fireball? Sorry sir. Washing my hair that day, sir.

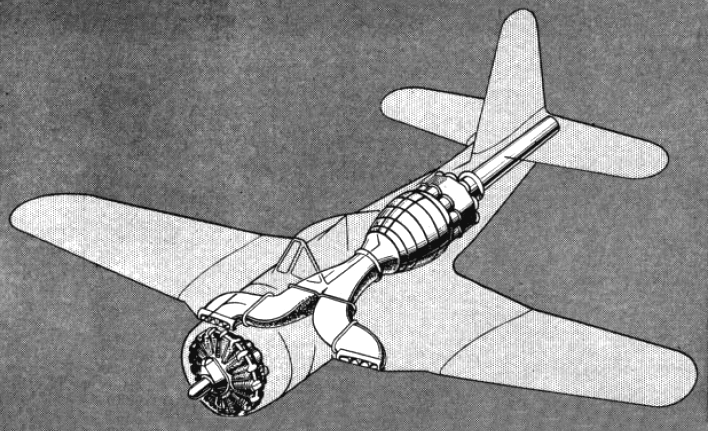

Yes, it& #39;s time to talk about the Ryan Fireball - essentially a conventional late-WW2 piston fighter with a jet engine shoved up its arse like the onion in an oven-ready chicken.

It& #39;s important to note that this strange turn of affairs came about through an entirely logical train of thought.

Logic only take you so far, of course. It& #39;s why Zeno stopped being such an insufferable smartarse when his fellow philosophers pulled out a bow and arrow and suggested he start running very quickly.

In the case of the Fireball, the US Navy were aware that early turbojets needed extremely long runways and powered up slowly.

Given the Navy& #39;s distinct lack of carriers two miles long this was a drawback for naval operations.

Given the Navy& #39;s distinct lack of carriers two miles long this was a drawback for naval operations.

However jets offered a massive advance in speed and altitude. Ideally the Navy wanted a plane with the advantages of piston and jet engines. The easiest way to obtain this, logically enough, was to fit a plane with both.

The Fireball was born.

The Fireball was born.

In this image of the jet installation the tail section looks disturbingly like the Stipa-Caproni Flying Barrel, and you have no idea how frustrated I am that nobody followed up on that hint...

One thread would not be enough.

One thread would not be enough.

Having settled upon this unholy union of mismatched powerplants, Ryan now had the relatively simple task of designing an aircraft to squeeze them into. It& #39;s at this point things started to go wrong.

Ryan& #39;s main experience was in building sports aircraft and light trainers. This is somewhat less demanding than building high performance fighters with the cutting edge of technology in their bum.

Following wind tunnel trials that suggested the plane had an issue with longitudinal stability, Ryan decided to style it out and see what the test flights revealed.

To great surprise the test flights revealed a horrifying issue with longitudinal stability.

To great surprise the test flights revealed a horrifying issue with longitudinal stability.

The ability to unexpectedly land backwards not being part of the Navy& #39;s original brief, larger stabilisers were hastily fitted and Ryan set about finding new and even more exciting problems.

It didn& #39;t take long for them to emerge. Ryan& #39;s experience with trainers hadn& #39;t prepared them for the challenges of flight at high speed.

The result was the disintegration of the first prototype& #39;s wings in a manner offensive to basic aerodynamics.

The result was the disintegration of the first prototype& #39;s wings in a manner offensive to basic aerodynamics.

Doubling up on the number of rivets seemed to cure things, but a second prototype was lost in a dive. Compressibility issues - aviation speak for air being a right bugger at high speed - were again suspected.

The third prototype, to everyone& #39;s relief, had wings that didn& #39;t appear to fall off at the slightest provocation. This was possibly because they& #39;d barely had the chance to fail when the canopy ripped off and the pilot lost control.

At this point it& #39;s a surprise that the whole project wasn& #39;t cancelled. Carrier operations are notoriously hard on aircraft and the Fireball wasn& #39;t exactly looking robust.

The Navy desperately wanted their new toy though, and carrier trials began.

The Navy desperately wanted their new toy though, and carrier trials began.

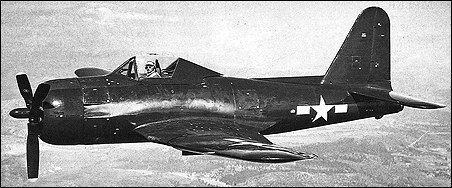

Despite the trials finding a few issues a production order was placed, and soon the first squadron was attempting to qualify for carrier operations. It was... not a success. Unsurprisingly the issue was the Fireball& #39;s fragility.

Attempts to qualify squadrons for carrier operations was regularly cut short by a lack of planes. The problem was usually the nose gear collapsing, but in the course of investigating this Ryan noticed the wings were showing signs of falling off again on several planes.

By 1947 the gig was up. One plane literally split in two during a hard landing and the Fireball was belatedly withdrawn from a service it perhaps should have never entered.

It did so having clocked up an important first. In its normal routine of falling apart one Fireball had the radial engine conk out. The pilot relit the jet and barely staggered into the crash barrier.

Unintentionally, this was the first carrier landing of a jet-powered plane.

Unintentionally, this was the first carrier landing of a jet-powered plane.

It would also be wrong not to mention the Fireball& #39;s party trick. Pilots delighted in pulling alongside other planes with the prop feathered and keeping pace with them, apparently against all laws of physics.

They& #39;d then accelerate and disappear...

They& #39;d then accelerate and disappear...

The ability to troll other prop pilots being of limited military usefulness compared to, say, the wings not falling off, this was hardly enough to justify the Fireball.

But I imagine it at least gave the pilots some compensation for having to fly the sodding thing.

But I imagine it at least gave the pilots some compensation for having to fly the sodding thing.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter