During the 1800s , the reign of Queen Victoria influenced many aspects of daily life. Her intense grieving after the 1861 death of her husband, Prince Albert, was felt long after he was gone.

Following Victoria’s example, it became customary for families to go through elaborate rituals to commemorate their dead.

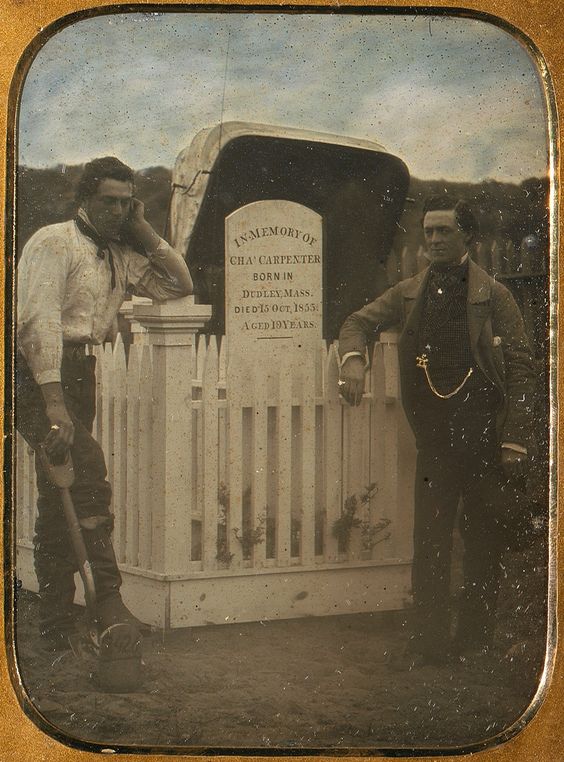

This included wearing mourning clothes, having a lavish (and expensive) funeral, curtailing social behavior for a set period of time, and erecting an ornate monument on the grave.

While we don’t follow all these rules today, these practices still influence how we think of death and funerals.

Victorian England was driven by the idea of a "good death," an elaborate and strict set of Victorian practices requiring painstaking detail and a small fortune. Failing to properly mourn on a grand scale was considered a societal and moral failure.

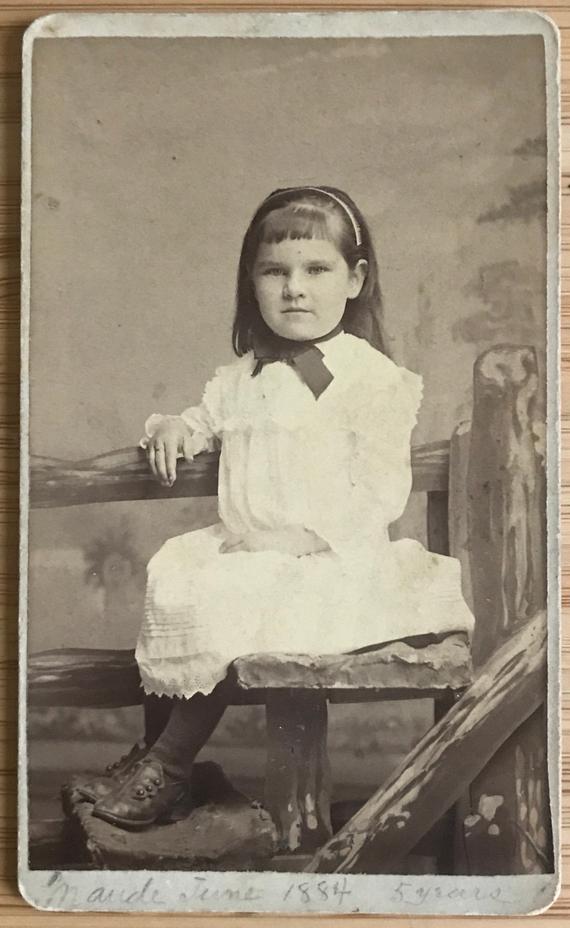

Considering that there was a high mortality rate at the dawn of the 19th century, especially among children (at around 50%), families found themselves perpetually ensconced in this macabre business during the Victorian era.

When someone of the middle or upper classes died, the funeral was the last chance for the individual and for the family to show the world how much they were loved.

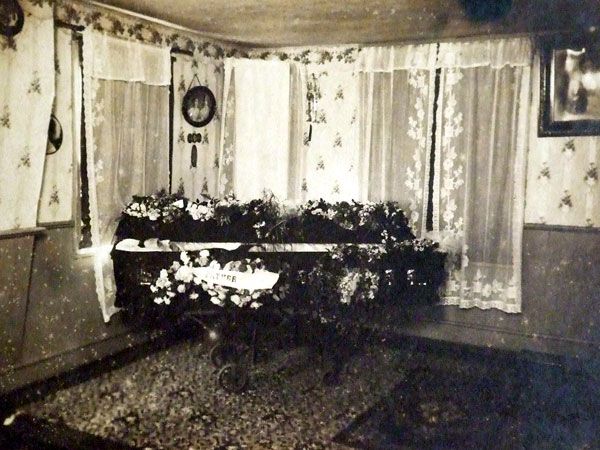

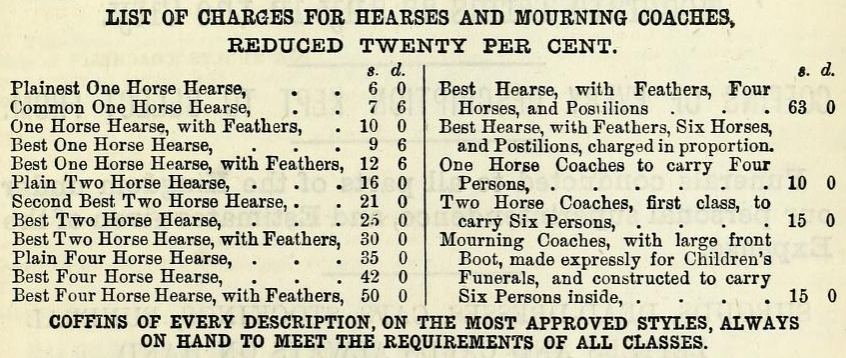

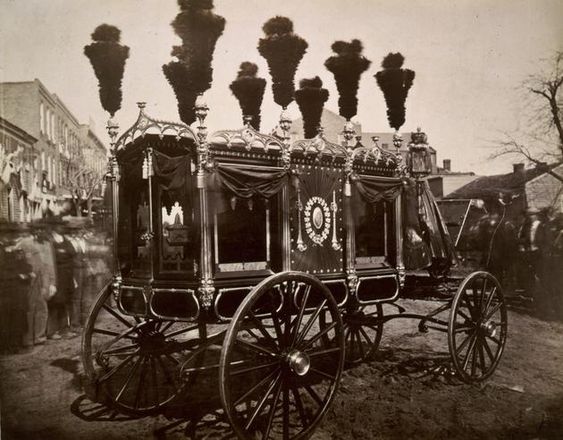

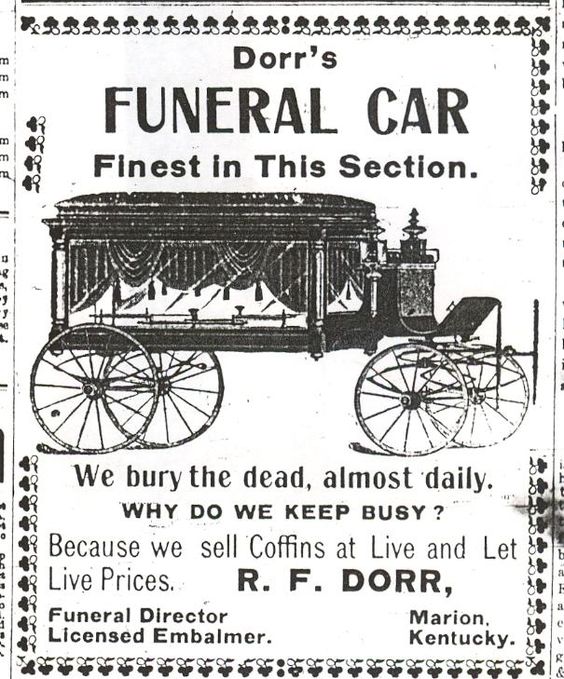

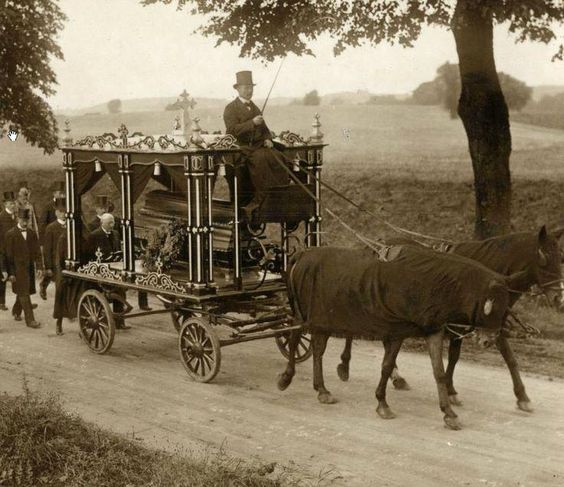

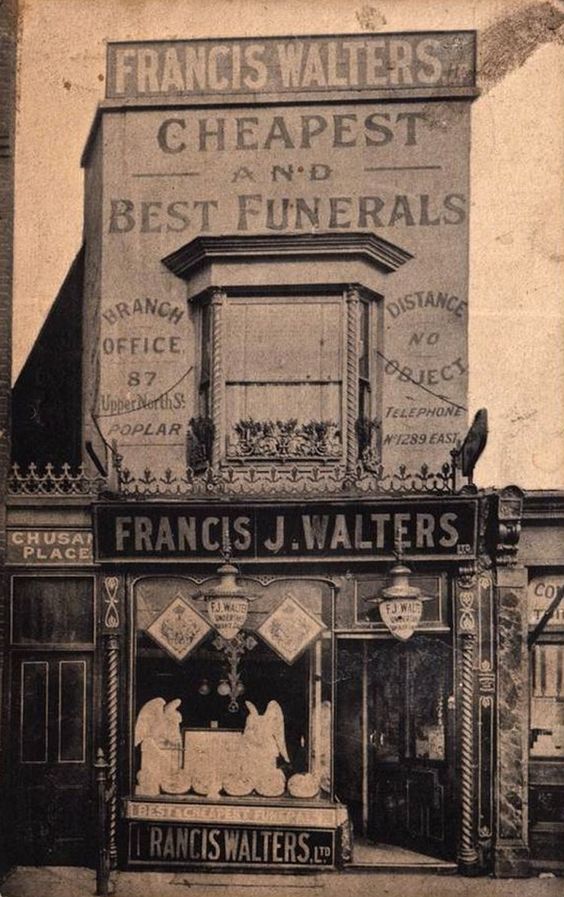

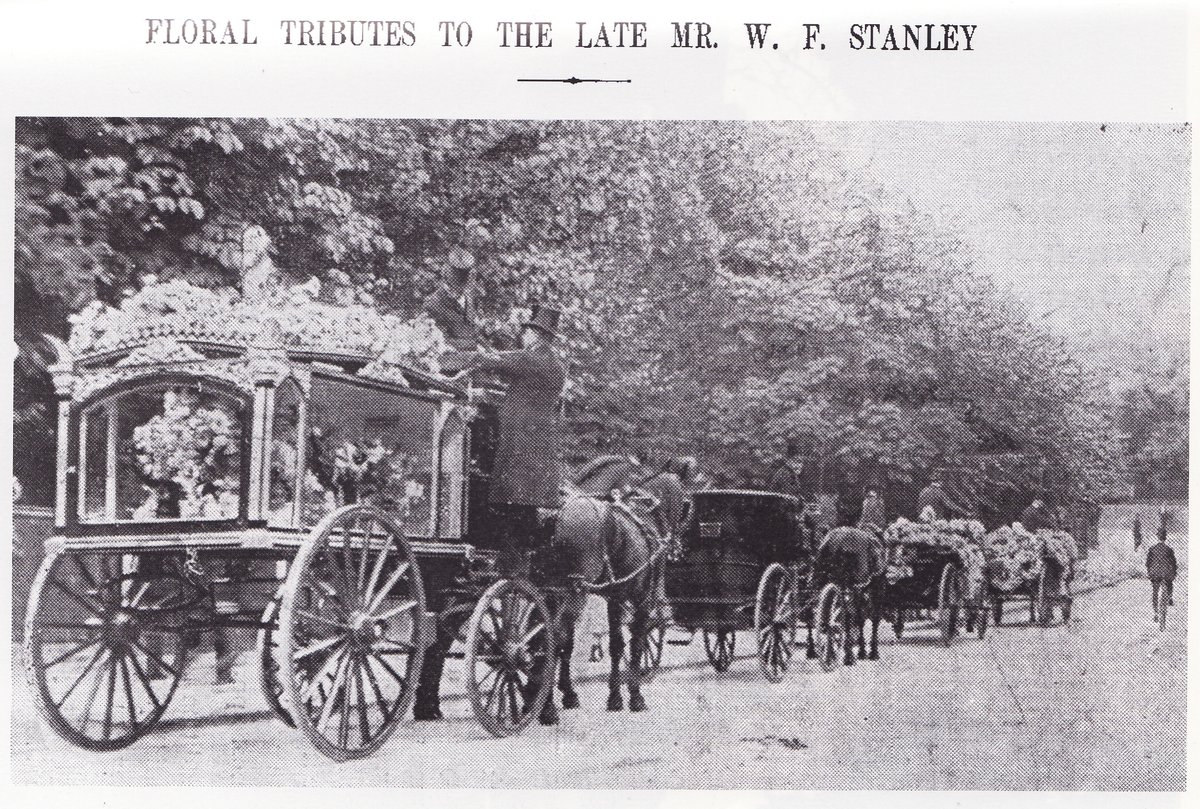

The more ostentatious the whole affair was the more it showed your wealth and status to the world. The finest caskets, carriages, and funerary clothes that a family could afford were purchased and displayed prominently.

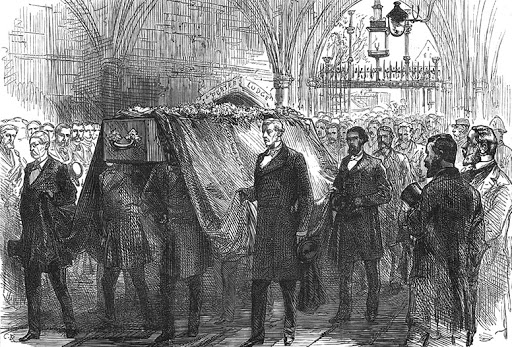

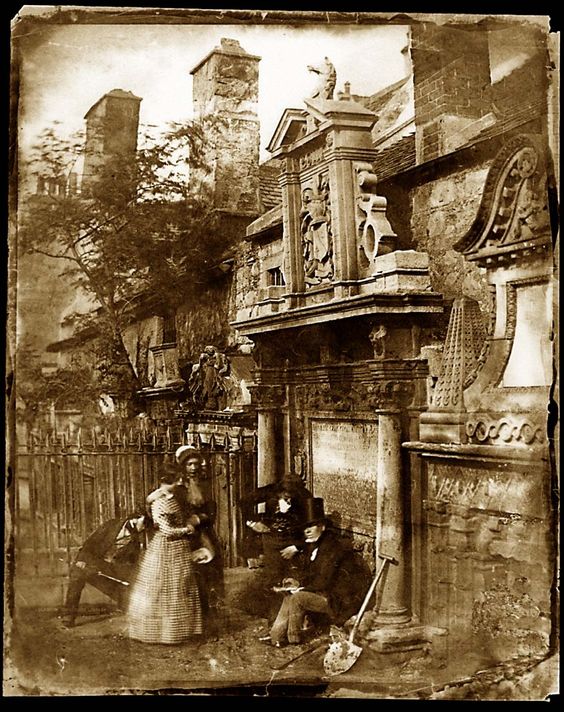

In the Victorian age, a burial ceremony was expected to be a long, elaborate, and public process - requiring a director, hired black horses for the hearse, elaborate floral displays, invitations, crêpe, pallbearers, photographs, and a large feast for mourners.

This is not an uncommon practice in other parts of the world – a stranger may be called in either out of compassion, ritual, or payment, to grieve for the recently deceased as if they were their own flesh and blood.

Poor families often scrimped and saved to make sure they afford a decent burial, as a nice funeral was seen as a mark of self-respect and standing in the community.

Some even went so far as to starve their living children to make sure they could properly bury their dead child. Families, particularly among the lower classes, began to set aside funds for an impending passing and the subsequently required pageantry.

By the mid-1850s, there were roughly 50,000 deaths a year in London. Townships were running out of room to bury the deceased, causing sanitation issues and health concerns.

While large beautiful cemeteries were built to hold the wealthy deceased, the poor faced a grisly fate. They relied upon the Poor Union to bury their loved one in a pauper& #39;s grave, without a headstone and with little to no ceremony.

Burial clubs were created to help families of the lower classes pay for services, much the same way modern insurance policies function.

Member paid weekly fees to cover expenses, no matter how long the person had been a member, with fees being based on age and type of ceremony.

During the declining period, the family sat with beloved members until they passed. Then it was customary for friends who were not members of the family to sit beside the deceased in order to spare the immediate family that added grief.

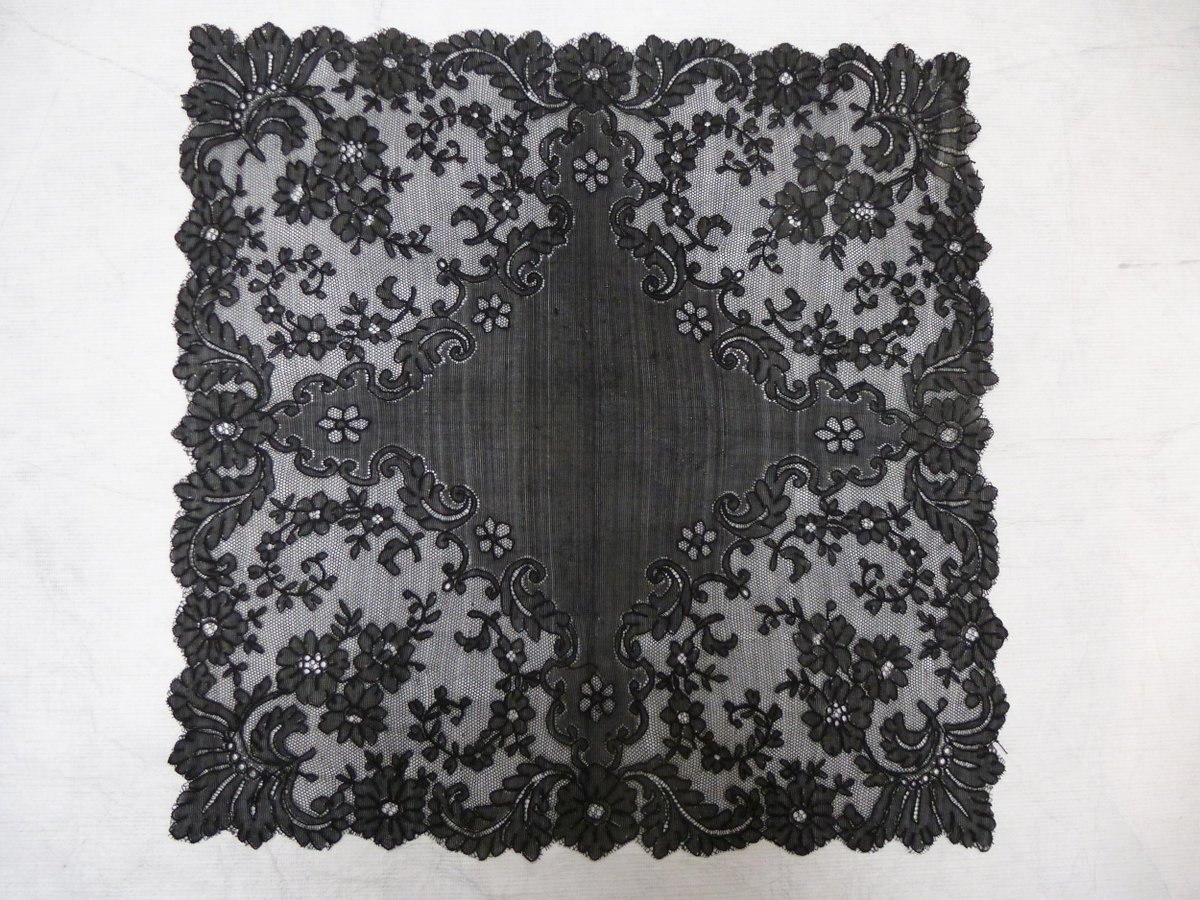

Black crêpe, a kind of expensive silk known as the fabric of mourning, was tied to doorknobs to let people know that the Dark Angel had taken something precious from the household and a knock or ringing doorbell would be a jarring reminder of life.

White crêpe was used if the deceased person was young or unmarried, signifying an additional loss of innocence.

One such tradition even dictated how the deceased was to be removed from the residence. The body was always taken out of the house feet first.

It was believed that if carried out head first, the deceased could see where the house was and return to haunt it. Additionally, the spirit that has not yet been laid to rest would be able to beckon other spirits or lure the living to their own demises.

If several or all members of a single household passed, anyone entering the home was required to wear a black ribbon, including dogs and chickens. The ribbon was believed to prevent death from being spread outside the house.

In the event that a beloved family pet passed, people of the era also held elaborate ceremonies for the deceased animals, particularly dogs. Despite class and wealth, families conducted dog funerals in the honor of their lost canine friends.

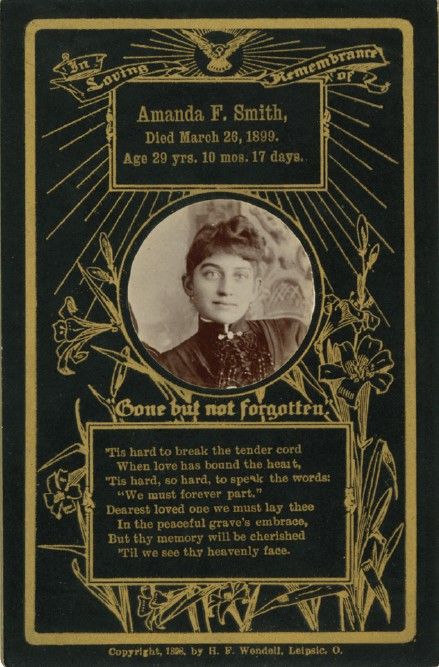

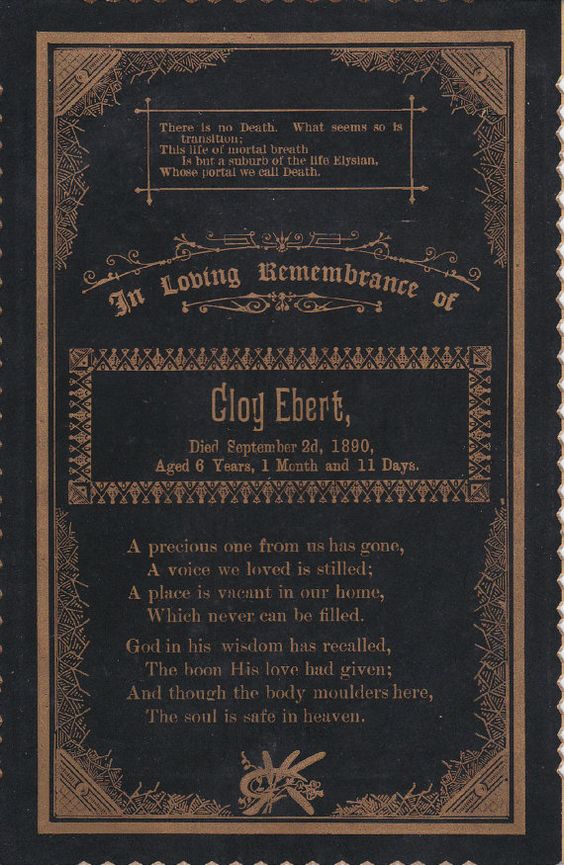

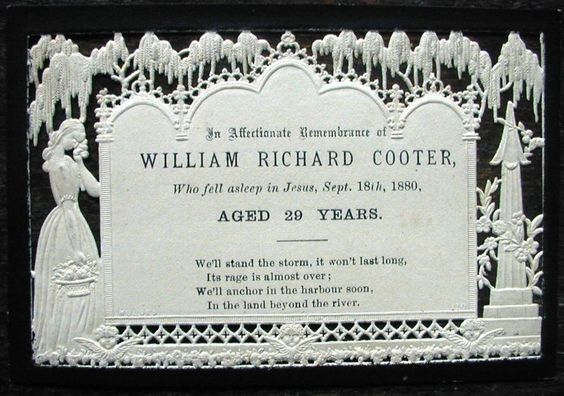

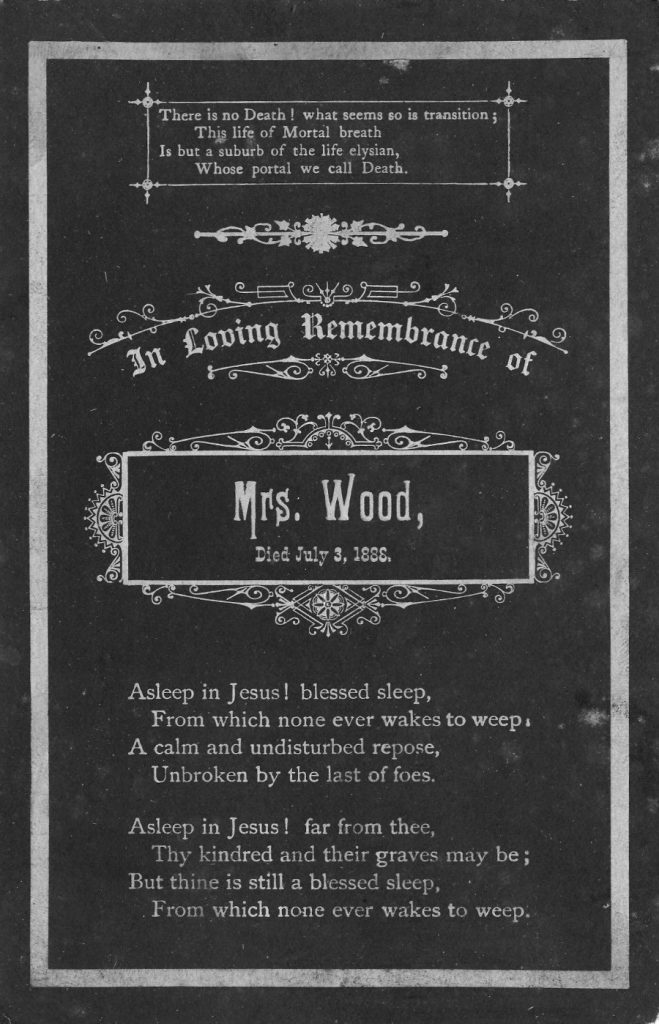

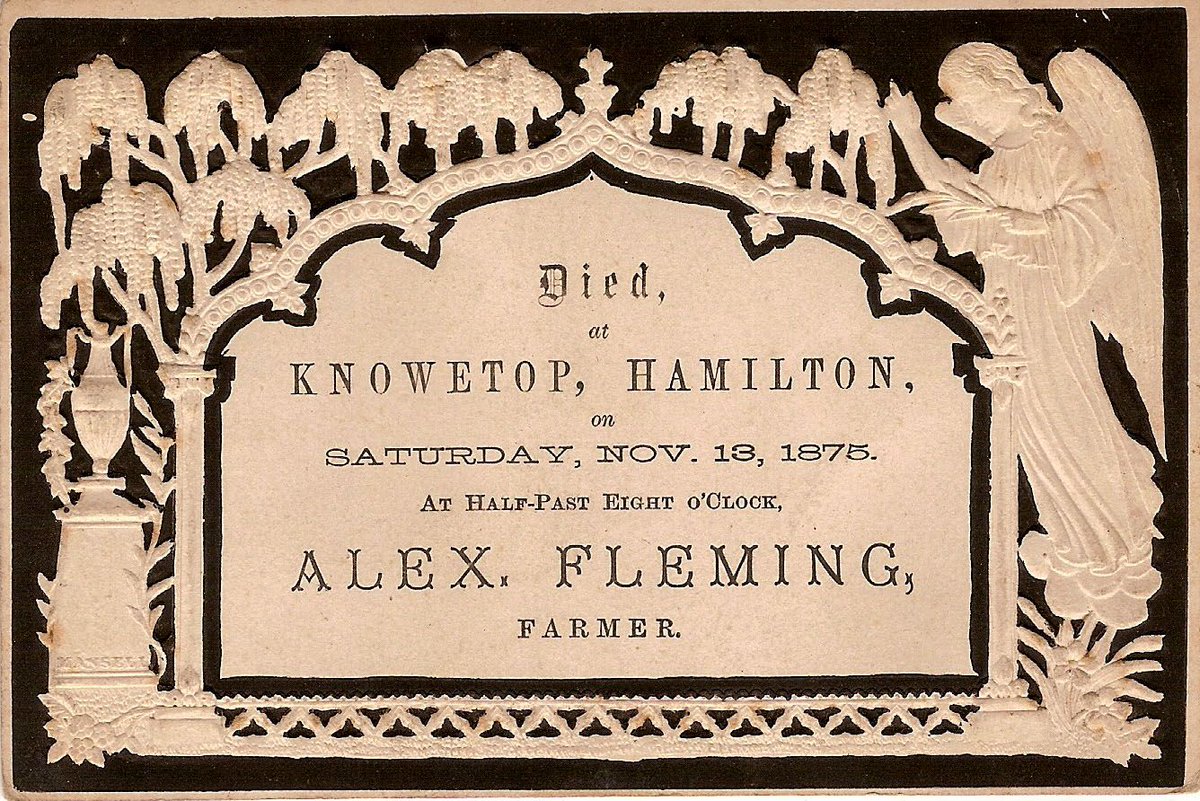

Mourning cards (also called funeral or memorial cards) were printed in classy designs, and later even had the departed’s photograph on the back. Cards could be embossed in gold, or they could be elegantly cut out in shapes like a Valentine’s card.

A mourning card was a sort of ticket to a high profile funeral. It was proof that you were invited and were close to the family of the recently dead. For large funerals of high status, the general public would certainly not have been allowed to attend.

For those of much more average social stature, the cards were printed as part of the funerary arrangements. Then after the funeral was over, the card served as a memento of the person and of the occasion, with the date and place recorded neatly in print.

The Victorian funerary procession was usually guided by a black carriage, which black or white horses pulled.

In the case of a child, a decorated yet small white carriage was used, and mourners walked behind the hearse instead of riding in carriages. White horses were also employed when the deceased was unwed.

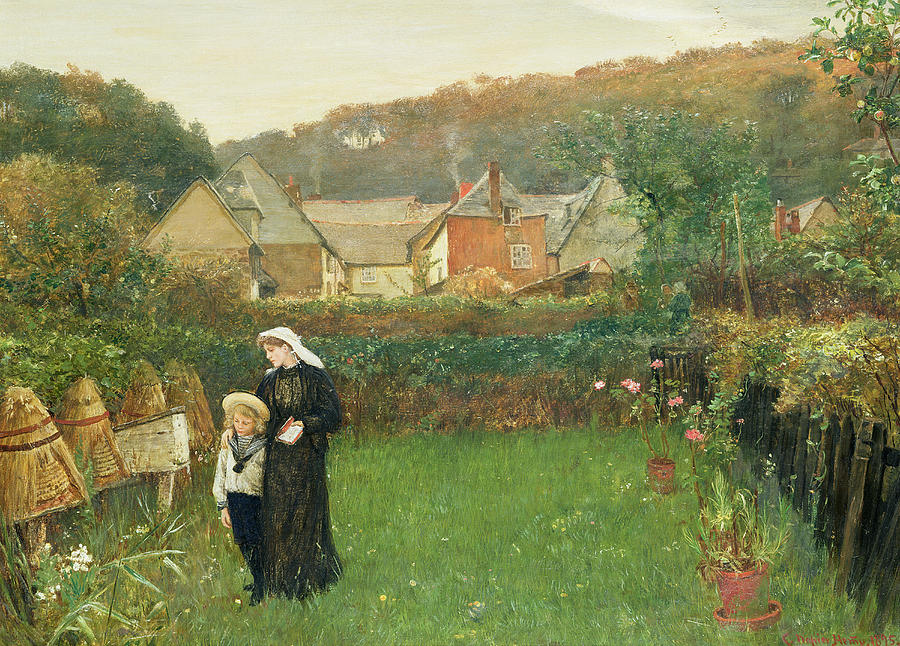

Victorian women in particular were hardest hit when their husbands died. At the time most women were dependent on men for financial stability, status, and even for social events. The customs of Victorian society dictated that widows acted differently than married women.

For a young woman who had recently lost her husband the heartbreak was overwhelming, but could also be debilitating.

For older women, being widow had some advantages in the end, as older widows could be much more independent, even if it often meant negative changes in status and income.

Servants were also expected to grieve, as Queen Victoria’s household knew all too well. She made the male servants staff wear black armbands for 8 years following Prince Albert’s death.

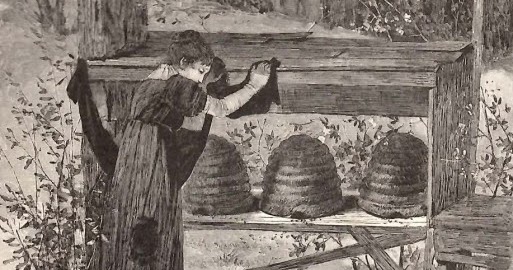

A symbol of mourning was to “tell the bees” about the loved one’s passing. Someone from the house would have the chore of informing the bees kept on the property of the death and sometimes the hives were even draped with black to show their mourning.

To forget the bees would be tantamount to sabotaging the hive, as the lack of mourning was said to hurt the bees.

While the traditions varied from country to country, “telling the bees” always involved notifying the insects of a death in the family—so that the bees could share in the mourning.

This generally entailed draping each hive with black crepe or some other “shred of black.” It was required that the sad news be delivered to each hive individually, by knocking once and then verbally relaying the tale of sorrow.

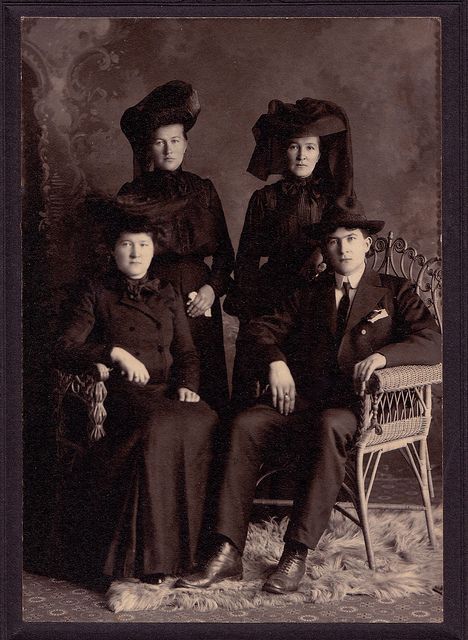

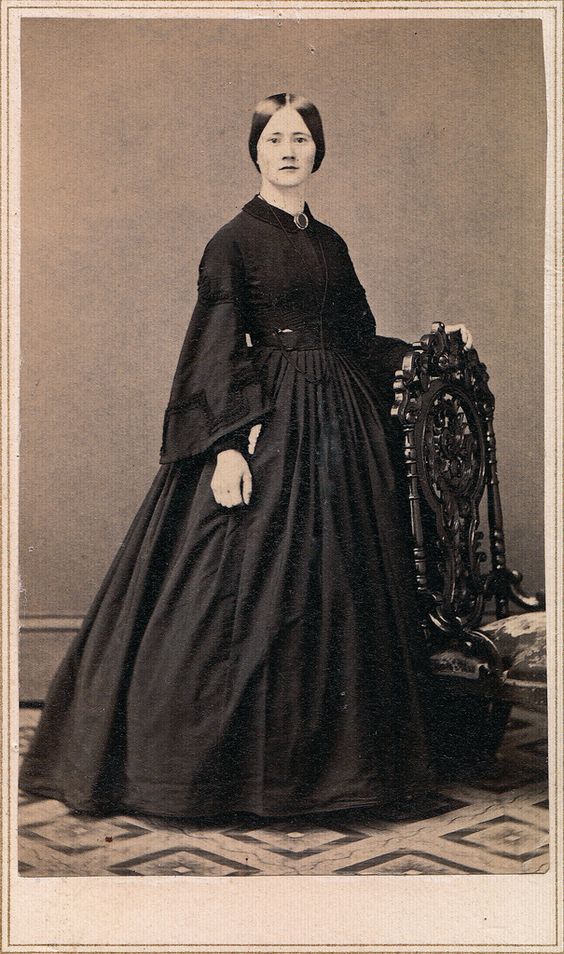

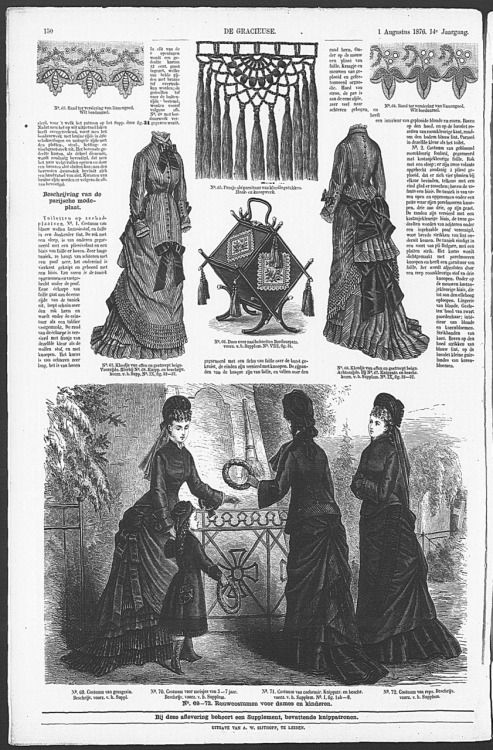

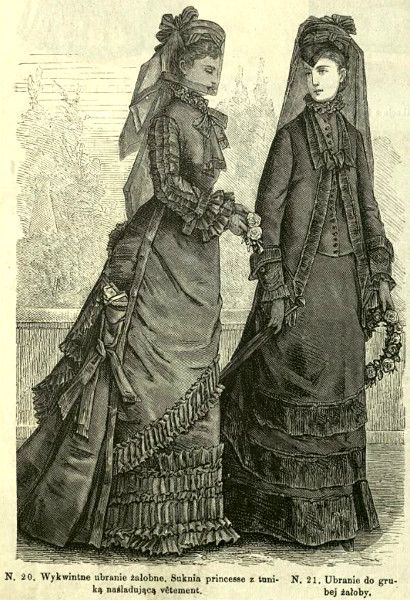

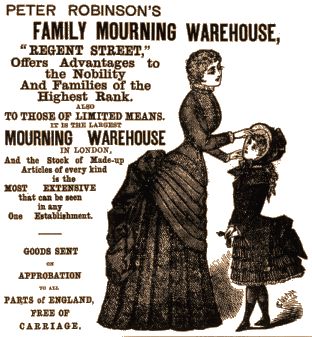

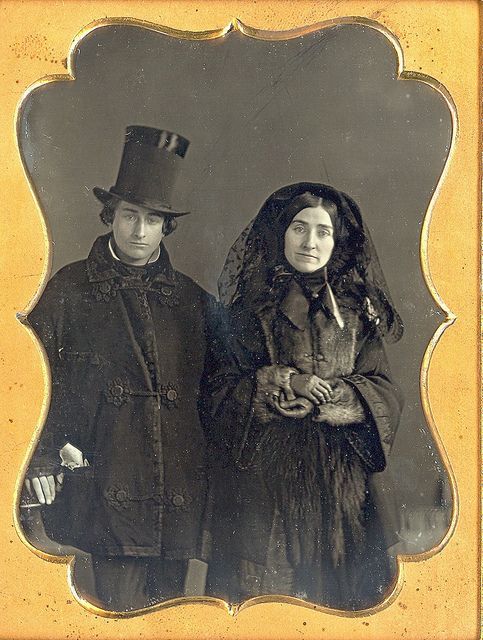

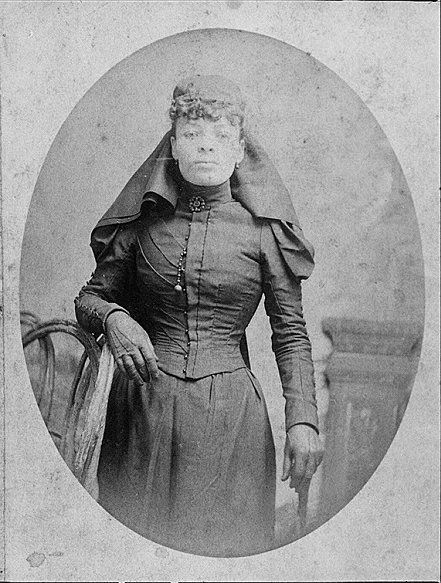

Mourning clothes were a family’s outward display of their inner feelings. The rules for who wore what and for how long were complicated, and were outlined in popular journals or household manuals such as

The Queen and Cassell’s – both very popular among Victorian housewives. They gave copious instructions about appropriate mourning etiquette.

If your second cousin died and you wanted to know what sort of mourning clothes you should wear and for how long, you consulted The Queen or Cassell’s or other manuals.

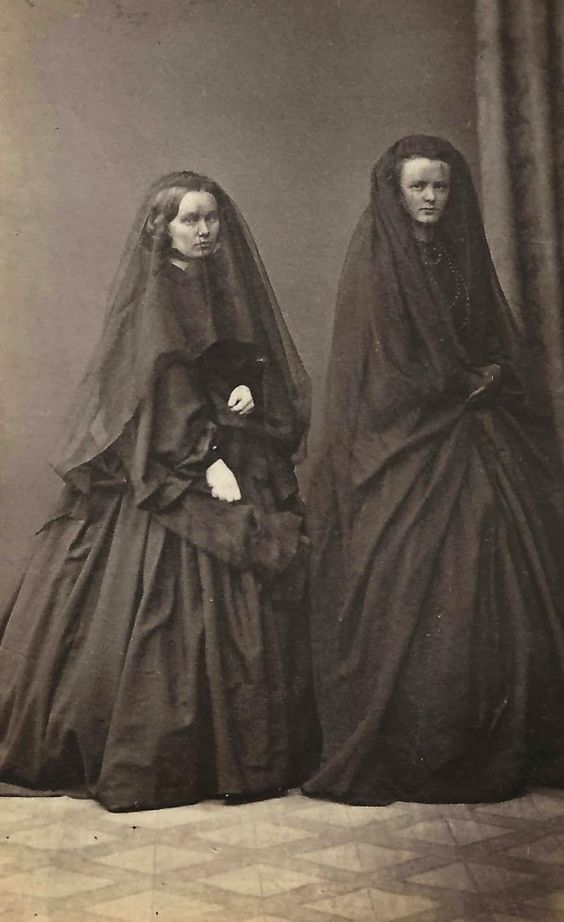

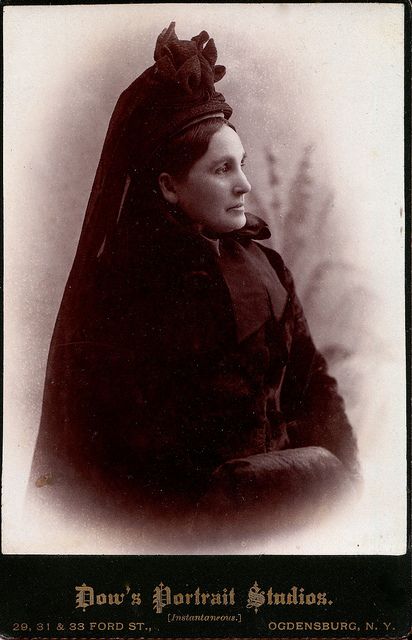

For deepest mourning clothes were to be black, symbolic of spiritual darkness. Dresses for deepest mourning were usually made of non-reflective paramatta silk or the cheaper bombazine – many of the widows in Dickens’ novels wore bombazine.

Dresses were trimmed with crape, a hard, scratchy silk with a peculiar crimped appearance produced by heat. Crape is particularly associated with mourning because it doesn’t combine well with any other clothing – you can’t wear velvet or satin or lace or embroidery with it.

The entire ensemble was colloquially known as “widow’s weeds” (from the Old English waed, meaning “garment”).

There were three distinct mourning periods: deep mourning or full mourning, second mourning, and half-mourning.

The first stage in the death of a loved one was the Full Mourning period, and the most dramatic. Full Mourning lasted for at least a year and changing out of full mourning dress early was a sign of disrespect.

Second mourning was of nine months and the veil was lifted and worn back over the head. The widow could wear minor jewellery. After the crepe was removed, secondary mourning colors like grey and lavender, or mauve could be introduced as trim on the black garments.

Half mourning lasted for three months and the widow was allowed to wear some color fabrics like grey, purple.

Exact time varies by region, but the move from full mourning to half mourning was gradual and happened in stages.

To change the costume earlier was considered disrespectful to the deceased and, if the widow was still young and attractive, suggestive of potential sexual promiscuity.

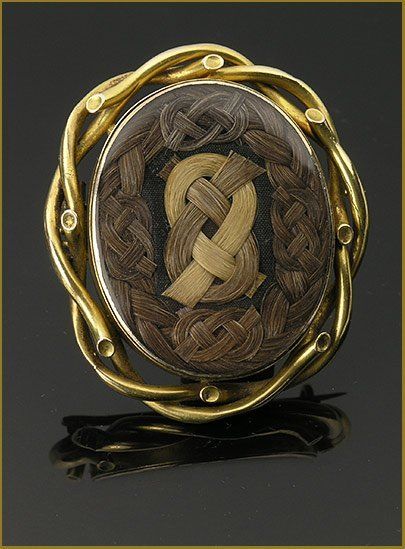

The latter part of the 1800s saw a market erupt for black glass mourning jewelry for the middle classes who could not afford the precious jet beads.

It is said that Queen Victoria started this trend by always wearing a locket of Prince Albert’s hair.

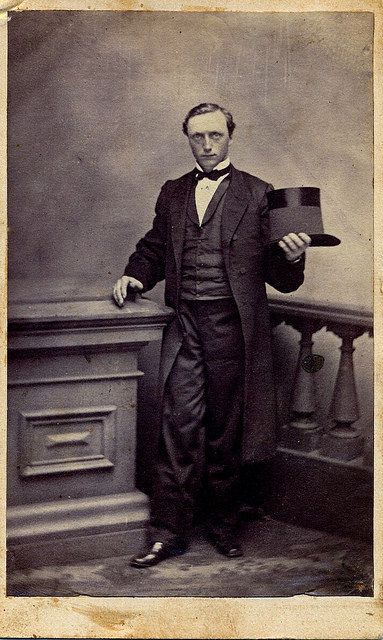

Men had it easy – they simply wore their usual dark suits along with black gloves and cravats. They also wore black bands on their top hat to show their mourning, and sometimes a black boutonnière was worn instead.

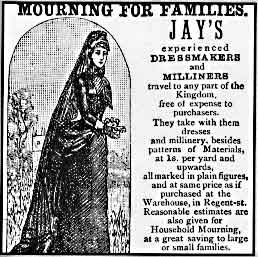

Someone had to provide the clothes quickly to mourners. Many shops catered to the trade; the largest and best known of them in London was Jay’s of Regent Street.

Opened in 1841 as a kind of warehouse for mourners, Jay’s provided every conceivable item of clothing you and your family could need.

And you were bound to be repeat customers: it was considered bad luck to keep mourning clothes – particularly crape – in the house after mourning ended. That meant buying clothes all over again when the next loved one passed. Mourning was a lucrative business.

The length of mourning depended on your relationship to the deceased. The different periods of mourning dictated by society were expected to reflect your natural period of grief.

While Queen Victoria’s move to remain in mourning to decades certainly influenced society, most women did not go this route. Widows were expected to wear full mourning for two years.

While women of little means sometimes did remarry quite quickly out of necessity, widows of wealth (like Queen Victoria) could afford to languish in mourning for much longer.

After two years and a day, the widow could come out of mourning entirely. She would send out cards to her friends and relatives, inviting them to come see her. She would invite them to fill her home up with life again.

The mourning of a parent was recommended for one year, as was the mourning of a mother for her child.

The loss of a sibling warranted only six months, and the loss of a wife mandated a measly 3 months of mourning.

A child was expected to grieve a lost parent for nine months (deep mourning) and then three months (half mourning).

Clocks were stopped at the time of the passing to honor the moment the soul left this mortal coil, and mirrors were covered in black or brown cloth up until the the funeral was over, usually about one week.

The stopping of the clock symbolized stopping time so that dead could move on. If the clocks were not stopped, then time would continue, thus allowing the spirits to remain in the present to haunt or endless roam in-between states of existence.

After the deceased was laid to rest in the ground, then the clock could be uncovered and restarted. However, if the head of the house passed, the clock would never tick again.

The mirrors were covered so that the dead would not get distracted and stay in this realm unwillingly. Family portraits and photos were covered or flipped to prevent the person& #39;s spirit from possessing the living.

It was considered bad luck to fail to do any of these death rituals after someone in your house died.

In the Victorian era, no one would ever think of telling a mourner that they had grieved long enough or that they should hurry up and get over it. Indeed it would have been a most egregious breach of protocol to do so.

Victorians were also very superstitious when it comes to death and mourning period. So they have assembled a bunch of superstitious rules such as:

-It is bad luck to meet a funeral procession head on. If you see one approaching, turn around. If this is unavoidable, hold on to a button until the funeral cortege passes.

-If you hear a clap of thunder following a burial it indicates that the soul of the departed has reached Heaven.

-If the deceased has lived a good life, flowers would bloom on his grave; but if he has been evil, only weeds would grow.

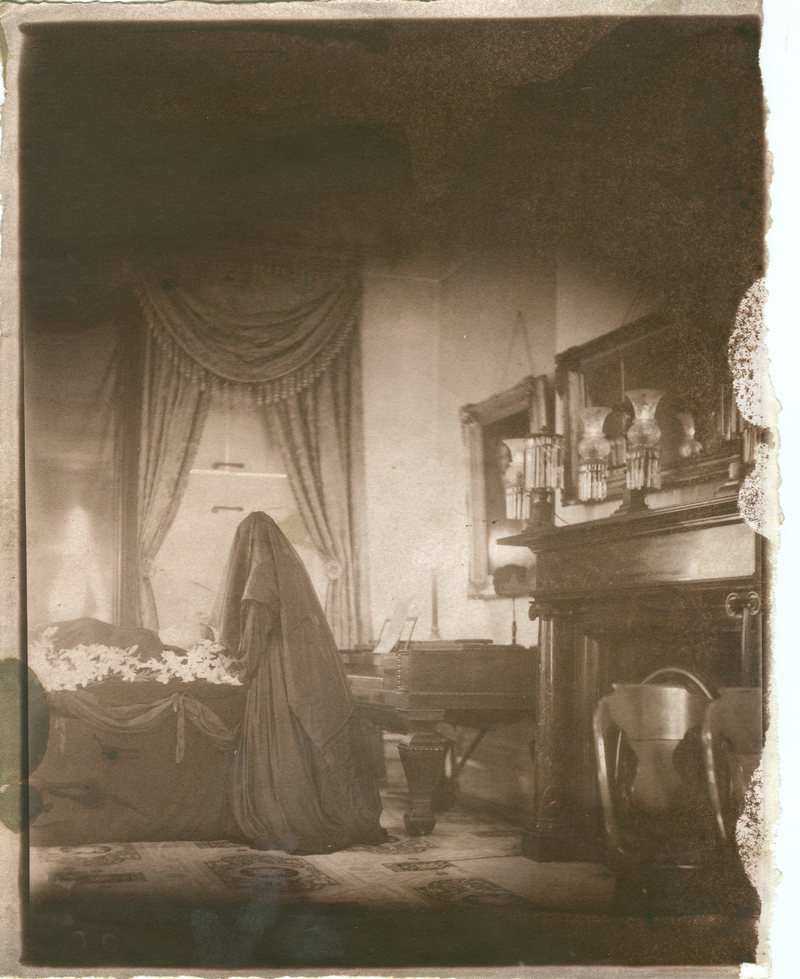

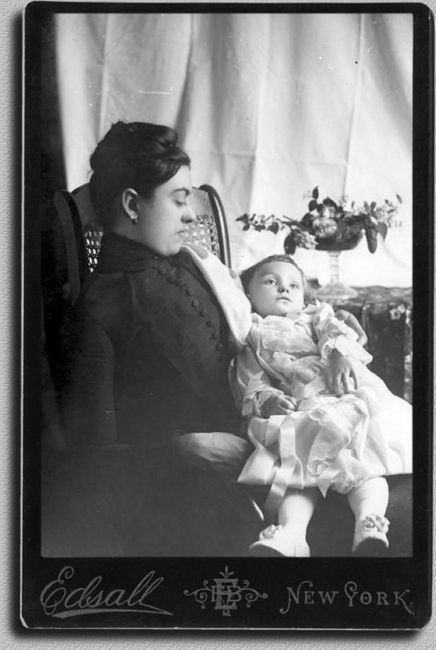

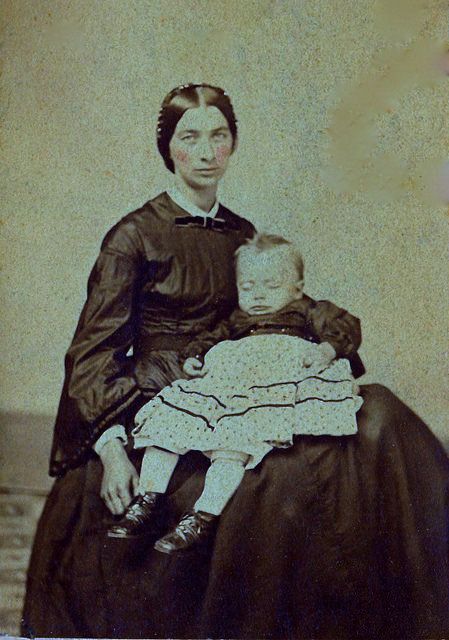

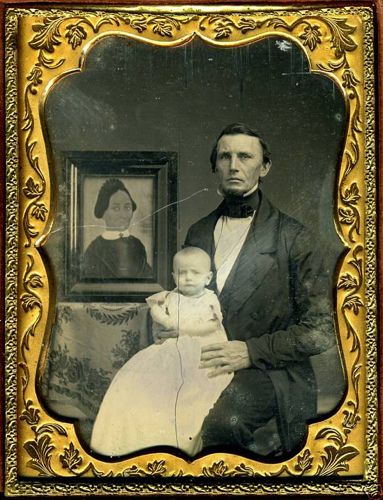

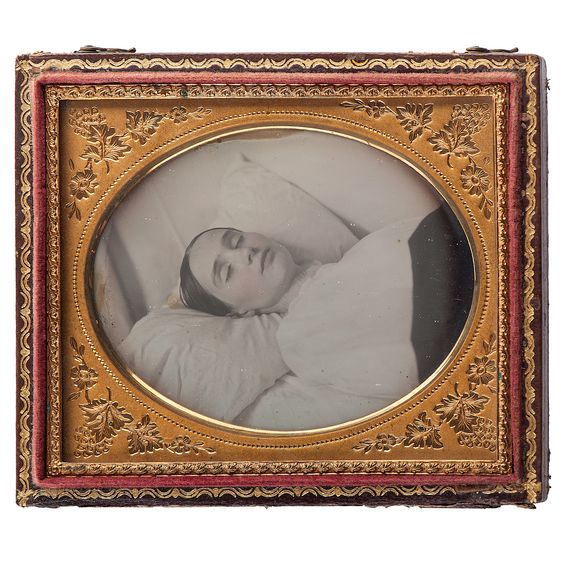

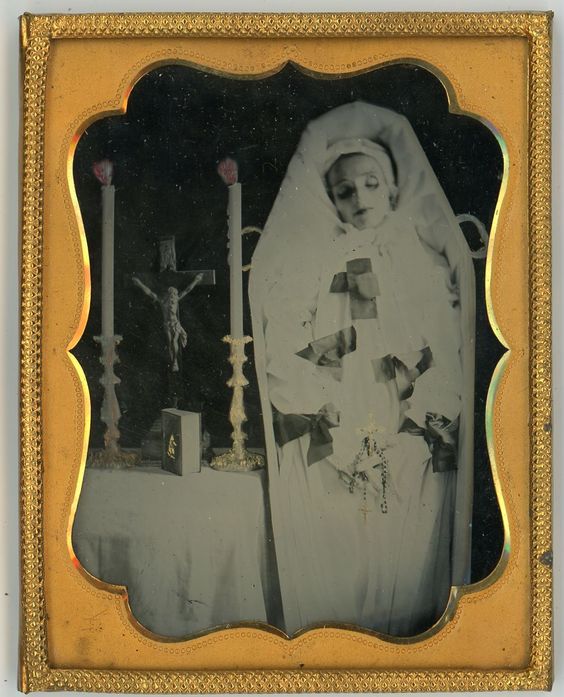

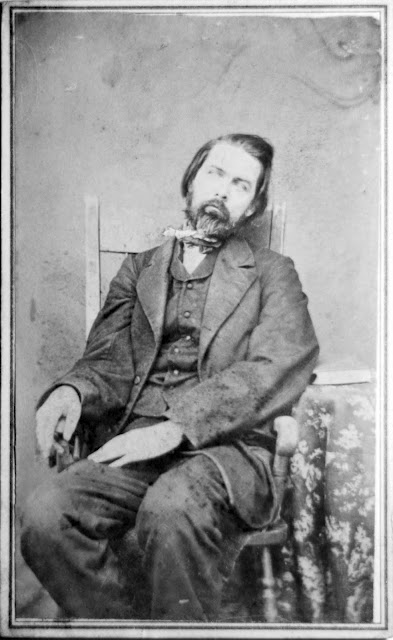

The invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre gave rise to post-mortem photographs. A common practice would be to pose the deceased in a realistic domestic setting.

Adults were posed in a setting in a posture as naturally as possible. Children were posed with family members, sometimes with a toy or sitting with a sibling, often times as though they were sleeping.

The deceased were sometimes posed standing, with the aid of hidden clamps and stands. In rare cases, "open" eyes would be painted on top of closed eyelids.

Since photography was expensive, a post-life photo might be the only photo the family had of the deceased. And due to the new affordability of memorial portraits, even the poor could commemorate their loved ones.

It was very important for mourners to be photographed in their deep state of grief. Photographs of the grieving, funerary flowers, the deceased, and other elements were placed in photo albums as a remembrance, as one would do with wedding albums.

Following the passing of babies and young children, families would sometimes commission mourning or grave dolls.

These were usually realistic wax effigies that would be dressed in the deceased child& #39;s clothing and sometimes even incorporate the deceased child& #39;s own hair.

The dolls had soft cloth bodies filled with sand that had a lifelike weight and feel, and flat backs so that they would lie neatly in their coffins

The dolls were usually left at the child& #39;s grave site, but some families would keep them in the home as a memento - in a small glass coffin, a frame, or even a crib.

During the Victorian era, women were tasked with the complicated business of mourning. According to the Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society, it& #39;s not surprising that these macabre customs greatly influenced even children:

By the 1870s, death kits were available for dolls, complete with coffins and mourning clothes, as a means of helping to train girls for participating in, even guiding, death rituals and their attendant grief.

In addition, many books and pictures geared towards children emphasized the duties of families in times of grief.

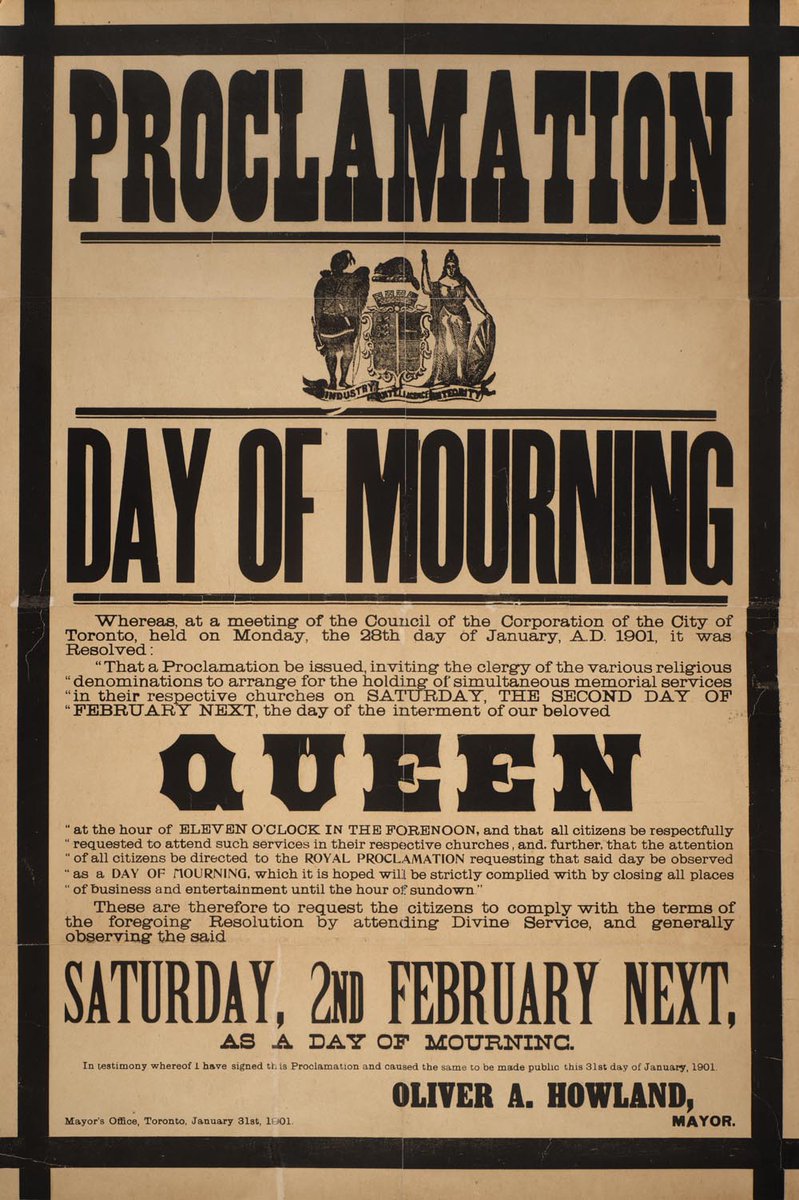

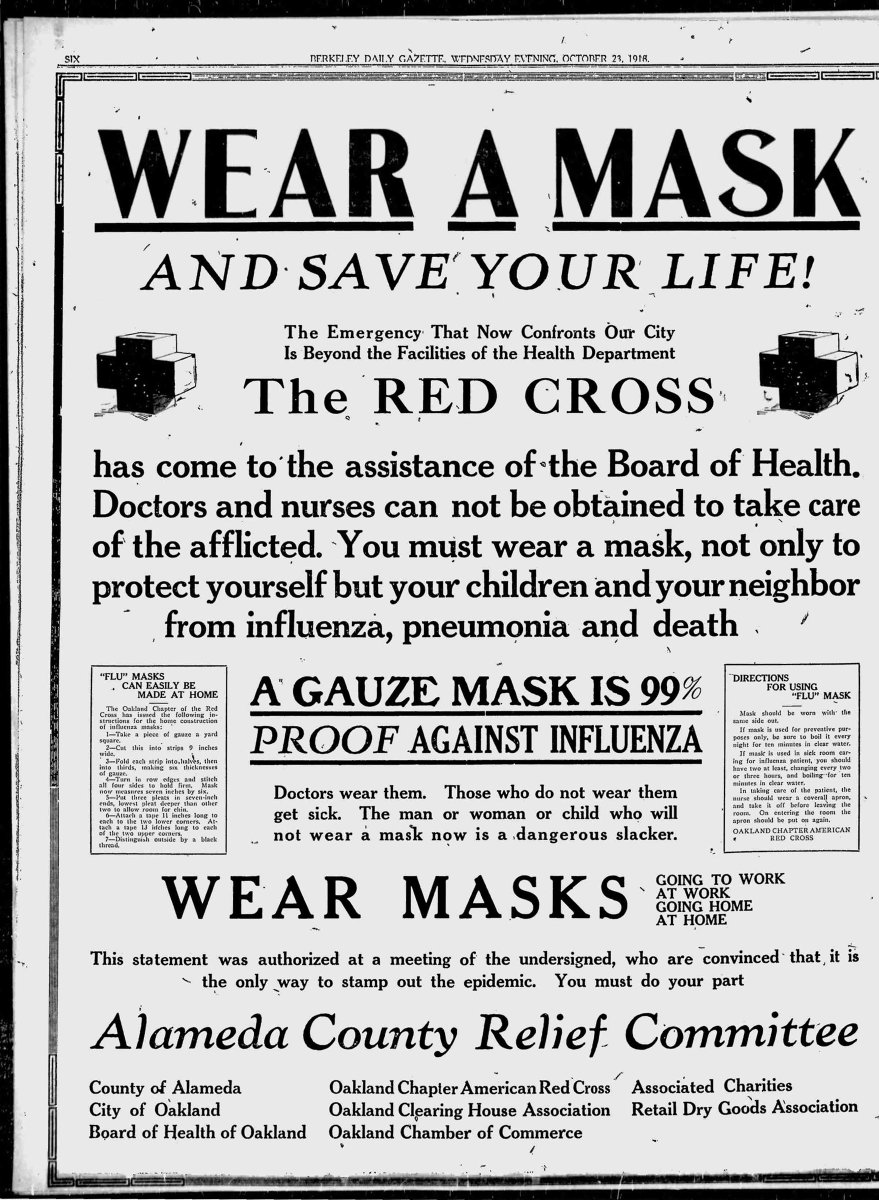

The stringent Victorian traditions waned with Queen Victoria& #39;s passing, the Great War, the flu pandemic, and an increased interest in cremation.

Thank you for reading until the end

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">

Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone"> Victorian mourning: A THREAD https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪦" title="Headstone" aria-label="Emoji: Headstone">">