Got waylaid yesterday, but, actually, I& #39;ma talk about this here, as I go. Because this thesis examines the ways we COLLECTIVELY (in current, anglophone YA) frame disability... #CripLit #PhDLife #DisabilityInKidLit

I want us all to think about it, to have these conversations and work to do better. I& #39;m not exempt. No book (whatever good it also brings to the table) is exempt, and we can ALL do better.

The thesis looks at all the major disability narratives I could find in YA from 2014-2018, some 328 titles, it looks at what rep there is, langauge, imagery & tropes, & how those are deployed. It& #39;s big picture stuff. It& #39;s critical.

This thread, however, looks at one example.Mine.

This thread, however, looks at one example.Mine.

Am I proud of TLLF and what it tries to do? Yes. Is it important? I think so... And I worked hard to make sure the rep was good and nuanced and valuable (as many, many authors do) Am I aware of some ways it contributes to some harmful ideas? Yes. And I& #39;m sure I missed some, too.

So. Some notes. I& #39;m sharing findings as I go: this thread& #39;s gonna be full of think-points, but MESSY. That& #39;s okay, the subject is messy, as is retraining ourselves.(But if you wanna use any of this anywhere, please come talk to me for clarified, eloquent versions:my DMs are open)

I& #39;m also STILL likely to miss things, or find things too small or scattered for the thread: doesn& #39;t mean they& #39;re unimportant, and I& #39;m absolutely up for hearing your opinions on representation, but, please don& #39;t use this thread for your own critiques unless they& #39;re invited.

This is SUPER SUBJECTIVE. It& #39;s hard to unpick language, wider context, intent and when that matters/ doesn& #39;t, and mesh it with your own knowledge of rep so far. It& #39;s harder when it& #39;s your own work. Someone else reading the same exact text will pick up on wildly different things

And let& #39;s recognise my privilege here: while I& #39;m a trans, queer, neurodiverse, chronically ill/physically disabled author, I am also VERY WHITE, and educated, and being paid to study. And, here, I was writing outside of (or adjacent to) my experience in a handful of ways...

Let us, too, recognise the work done by those before me: disability scholars & publishing folks alike, working across multiple fields & multiple intersections to help us do better for readers. (Too many incredible people for THIS thread, but, I& #39;ll tweet another in due course.)

And, finally (I think), before I get started, if I reference other titles for wider contextual purposes, it is expressly for that purpose. I& #39;m not picking on anyone here, merely looking at the representation we, as an industry, as a whole, are offering disabled people.

Heeeere we go, a critique of my own past work, in regards to disability representation.

Of note: I’m looking at the UK text, markedly different to the US text, in that there’s an extra suicide-club plot thread.

(This is, uh, Many Tweets. Bring snacks and buckle up, I guess?)

Of note: I’m looking at the UK text, markedly different to the US text, in that there’s an extra suicide-club plot thread.

(This is, uh, Many Tweets. Bring snacks and buckle up, I guess?)

This book explores autonomy, dignity, end of life care and assisted suicide. I tried to leave space for readers to think about hard questions, rather than provide a view one way or another.

It necessarily, then, explores reasons one might want to end life on one’s own terms and THIS means confronting both some hard physical truths about some experiences of disability, and some harder ableist social structures and opinions.

Does that make the book inherently ableist and awful? I don’t think so. But it DOES mean there are multiple words, images, interactions which ARE ableist to some degree.

There’s a lot to unpack in the text. Some bigger, more important things than others (for this text, rather than more important overall). Some areas are related to others/ interweave, some are standalone.

I’m going to talk about: language; what makes a life ‘worth’ having; disability as burden; lack of agency, disability as shameful; as horrific; as undesirable; how his wheelchair is discussed; cure as the ultimate goal; disability as inspiration porn.

First! Instances of language. I’m tracking slurs and other key words across every title I critique. I worked consciously when drafting NOT to use ableist language, but a) it is pervasive, and b) my understanding of what that constitutes has radically changed since 2012/2013.

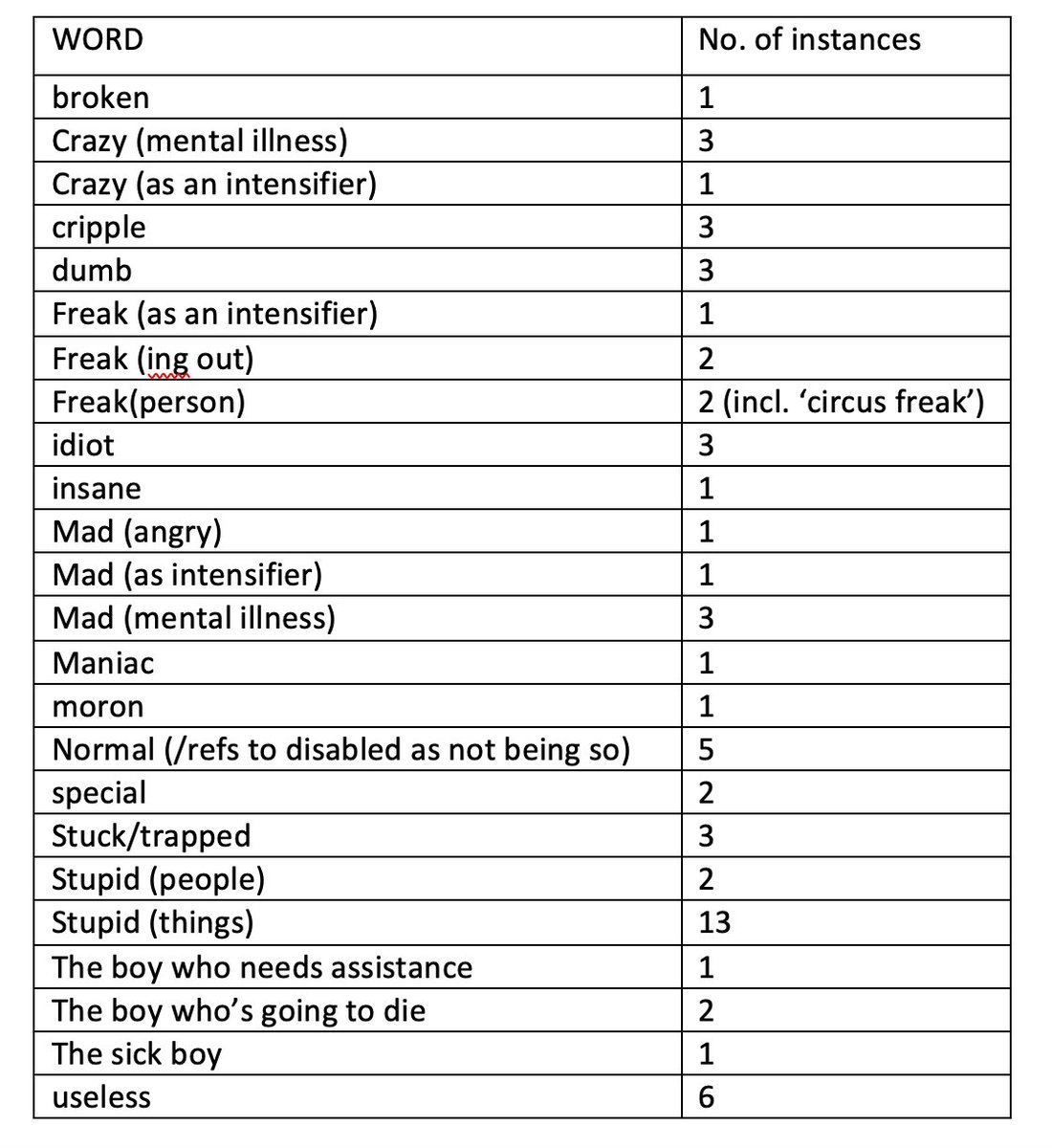

In TLLF, you& #39;ll find:

You’ll also find 2 instances of the word ‘pity’, one of ‘revulsion’, one ‘unfortunate’, and 27 instances (out of 34) where the word ‘sad’ refers to Sora and/or his situation.

This is casual language stuff: the words we by and large use without thinking. like ‘crazy’ and ‘stupid’, and ‘normal’ which might not seem particularly bad. But they do lay the groundwork for our (/society’s) notions of normal, good, productive lives...

...of intelligence and success (things largely accessible to those who fit the system). They underpin everything that follows.

If you, too, would like to search for all the terms I log (there are more which TLLF doesn’t use) in YOUR work, and to replace or at least interrogate your usage, HMU for a list (I& #39;m tracking 54 terms & some cultural refs, and noting patterns elsewhere): we can all do better :)

Next up: Life’s worth.

There’s a thing that a LOT of acquired-disability narratives do where they focus on the things a character loses, physically, academically, socially… TLLF is not immune to that trap.

There’s a thing that a LOT of acquired-disability narratives do where they focus on the things a character loses, physically, academically, socially… TLLF is not immune to that trap.

Indeed, while sports was not a large part of Sora’s life, his ALS first makes an appearance when “out on the baseball field, I fell.” (2) This wasn’t conscious writing, but it increases readers’ sense of that physical loss.

He wants to go to school, to learn, to become a professor. Mainstream school is not equipped to handle him physically accessing the classroom, and though his mother argues for him (“he’s such a bright boy. He studies hard. It would be such a waste.” (35)) he ends up at home.

There’s a special school, but he has feelings about it: “I am NOT a special student.” (11) and about the quality of education there/ society’s perception of that education: “Even if I am around…no one graduating from a special school will get a place at university.” (11).

And out of school, he loses his sense of self. “All I am now is a failing body. A boy…who will not achieve.” (23)/ “Once, we talked of grades and universities…now all I have to report is the latest shaking muscle, and we don’t say much at all.: (48)

His ableism is showing, and while it doesn& #39;t lean heavily into it, the narrative doesn& #39;t really unpack or dismantle notions that our academic/career potential might be our worth, or explore the potential and value of education outside of mainstream tracks.

The prevailing notions here are those of education (and where it leads) as capital-I-Important, and of his (/ others’) success within the education as a measure of their worth.

This is…genuinely not what I believe, though society mirrors and compounds those ideas, and yet, somehow, here it is in my work, plain as anything.

There is a notion that needing support (to access inadequate, ableist systems and environments) makes us burdens. Indeed, ‘burden’ is a key part of Sora’s thought process and experience, and factor in his ultimate decision.

His mother is referenced as ‘tired’ 9 times, as she has been ‘ever since his diagnosis’ (3). He sees her sadness, talks about all the extra care he’ll need, the extra shifts she’ll have to pull to afford equipment to manage; how he’s going to break her heart.

He talks about being a burden to his grandparents, not being the grandson they deserve.

And (from a different angle) because he cannot do it by himself, he finds himself placing the ‘will you help me die on my own terms?’ burden upon his friends.

And (from a different angle) because he cannot do it by himself, he finds himself placing the ‘will you help me die on my own terms?’ burden upon his friends.

Assisted dying is controversial. It’s not an easy topic. Activists have much to say on both sides, and I think – I hope – I was careful to allow readers the space to think about it for themselves.

Further to agency and control, though: Sora is losing his in pieces. His body is gradually responding less. He finds himself needing increasing help to handle self care, and to move around...

...He does not know how long it will take, or what function he’ll lose next, only that it’s going to happen and he cannot stop it.

And his mother sometimes takes his independence from him before it’s strictly necessary, offering help with tasks before he’s ready to stop doing something for himself, managing his medications rather than trusting him. Once, he starts cooking while she’s out, as a surprise...

He finds he& #39;s missed it, revels in the task even while it& #39;s physically taxing. But when she gets home, she is angry, and stops him because “you might fall, or cut yourself…I will not risk it. (93)

Next: Disability is shameful, right? “It’s…difficult. Embarrassing. No one wants to be around us any more.” And “Every time I hear the door, the telephone, a stranger’s voice, I wonder, who else is going to know my shame?” (4)

Sora thinks of his disability and the ways others will see him A LOT. He does not tell his friends (online) that he’s in a wheelchair until they show up to meet him IRL. He’s worried about appearing a mess.

Worried about and ashamed of the human body and all its failings and fallibilities and messiness. When he cannot make it to the bathroom, he’s ashamed (71). He worries about shaky hands making him spill food and embarrass his friends, about not being able to do things.

And he’s certain that at the end “I don’t want to end in a puddle of my own waste, gasping for breath like a foul stinking fish.”(82)

When he encounters men in palliative care, you get HORROR imagery: skeletons, unnatural, glassy eyed stare, already dead, feed, turn unsuspecting victims… “and I just saw my future.” His inevitable end is set up here as a horror story.

(And again, I did not consciously pick this language, though I knew the emotions he would feel. The language sunk in, I think, from decades of exposure to the ways we discuss disability and death.)

(Conversely, TLLF handles ‘noble’ death of the Samurai with almost the opposite: peaceful, calm, natural language - mountain air, cherry blossoms, steel, honour, sing, free, kiss, laughing, rest...

... He reads these after moments of laborious effort and stress, and notes “many of the poets talk of death, the act, as the thing which sets them free.” (78))

All of this, and is it any wonder that we see disability – and the disabled – framed as undesirable? Many books in my corpus have the ‘disabled character as ugly, unsexy, unlovable’ narrative at the forefront.

It isn’t a major narrative here, but you still get one line, “what girl would ever want a boy who cannot feed himself? That’s where you’re heading.” (67)

It’s a throwaway line, it has no bearing on the plot. It still upholds those same views being offered to readers elsewhere.

It’s a throwaway line, it has no bearing on the plot. It still upholds those same views being offered to readers elsewhere.

(And uh, I’m a disabled guy, with a disabled partner. I ABSOLUTELY do not believe that nonsense. But it’s so prevalent that it sneaks into our consciousness, and the more we express or consider or give it space in public, the more we perpetuate it.)

Let’s talk about Sora’s chair. Wheelchairs are ubiquitous with disabled imagery, right? Familiar symbols/ what many people think of at the word ‘disabled’.

(In fact, Sora uses that to find out what his peers’ reaction to his own situation might be, asking them for their first thoughts on an image of a boy in a wheelchair)

His chair is mentioned 61 times in the text: 44 times, neutrally, describing, eg, placement or how he’s getting around. Twice, he mentions it in positive terms, as a thing which offers him freedom and comfort.

Fifteen times, Sora expresses some pretty negative feelings towards his chair – or, toward his own lack of mobility and independence.

(it is worth noting that the neutral also includes him getting to go out with his friends and to maintain some independent movement long after he otherwise would...

...that the negative is in line with his general mood trajectory and his physical decline, not specifically an issue that he has with his chair. But that doesn’t DISCOUNT those negative moments.)

Finally (on chairs), when his friend creates him an escapist comic series, his character, Professor Crane, is sad, until his animal friends make him robot wings, allowing him to leave his chair and fly...

...The characters’ subsequent adventures bring Sora comfort/distraction/time with friends in later stages of his illness. But if I were to write this book again, I’d have them do that differently, without framing the wheelchair as a static, unhelpful thing to be overcome.

Cure as goal: this one is hard to discuss in relation to TLLF, since NOT having a cure means certain, imminent and uncomfortable death (as opposed to narratives where long, fulfilling, joyful lives with disability are absolutely possible, and even the norm).

However: Sora wishes for a cure x3. And while there is plenty of joy and friendship and love, this book ultimately focuses on his decline, and all the ways he will not get to live beyond the pages of the book.

(the cure-as-goal narrative is problematic, and often used in ways that undermine disabled lives and experiences, but there are folks who would take a cure - for any number of disabilities - without a second thought, and that is absolutely valid.)

And then there’s inspiration porn. At the beginning, Sora is asked if he’ll make a speech at the last baseball game of the season ‘to motivate the others’. He declines, because he does not want to be an inspiration.

He’s angry at the offer of a sick kid’s Wish (the kind that allows for holidays and meeting heroes and such), and the professional who offered seems confused by his refusal, “As if it were a personal snub, as if her offer isn’t good enough.” (58)...

...Wishes, here, are set up as a do-good thing, in line with an able-saviour narrative, wherein ‘helping’ a disabled person is more about making the abled person feel good than about what that person actually wants or needs.

Sora does not want to be an inspiration. But he inspires his friends to pursue futures that they want.

And they, in turn, combat an awful ‘life isn’t worth living’ chain letter/ suicide pact (subthread throughout the book) with a wishing tree website, encouraging more people to strive for things, and make the most of time they have.

Their website shares his story, and he does, ultimately, become that inspiration to others. And to readers. Part of the (US) marketing campaign for TLLF was the production of that website. And I’ve had readers send me ‘Sora made me realise how good/ important life is’ letters.

TLLF is a sad book, and a hopeful book, it meditates on some hard, complicated grey-area issues. And I hope – I think – it does a good job of portraying Sora’s journey fairly and with care and nuance.

I hope it demonstrates how a disabled boy in all his intelligent, thoughtful, caring, flawed-and-messy glory, handles an impossible situation, and makes it clear that his path is - absolutely - not the only one.

There are good, positive, loving relationships, fun and laughter. agency where he can get it, and confronting some of the systems where he can’t.

But it still sits within a wider corpus, wider media portrayals and wider cultural understandings of disability, and it still echoes some of that, and falls into pitfalls that I didn’t notice at the time.

And that’s why I’m doing this PhD. Because we aren’t all aware of every trope, or origin/ use of language, or nuance of experience. Nobody can witness or live through or know everything…

Because we don’t spend enough time questioning the cultural truisms and assumptions which underpin society and get hashed out in a thousand ways across our media – we are comsumers of those stories, and it shows.

And we can ALL do better. And we must, because right now, even our relatively good rep, when it is amassed, does not allow disabled people (characters, readers, neighbours etc) all the hope, grace, and opportunity that able bodied folks get repeatedly and automatically.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter