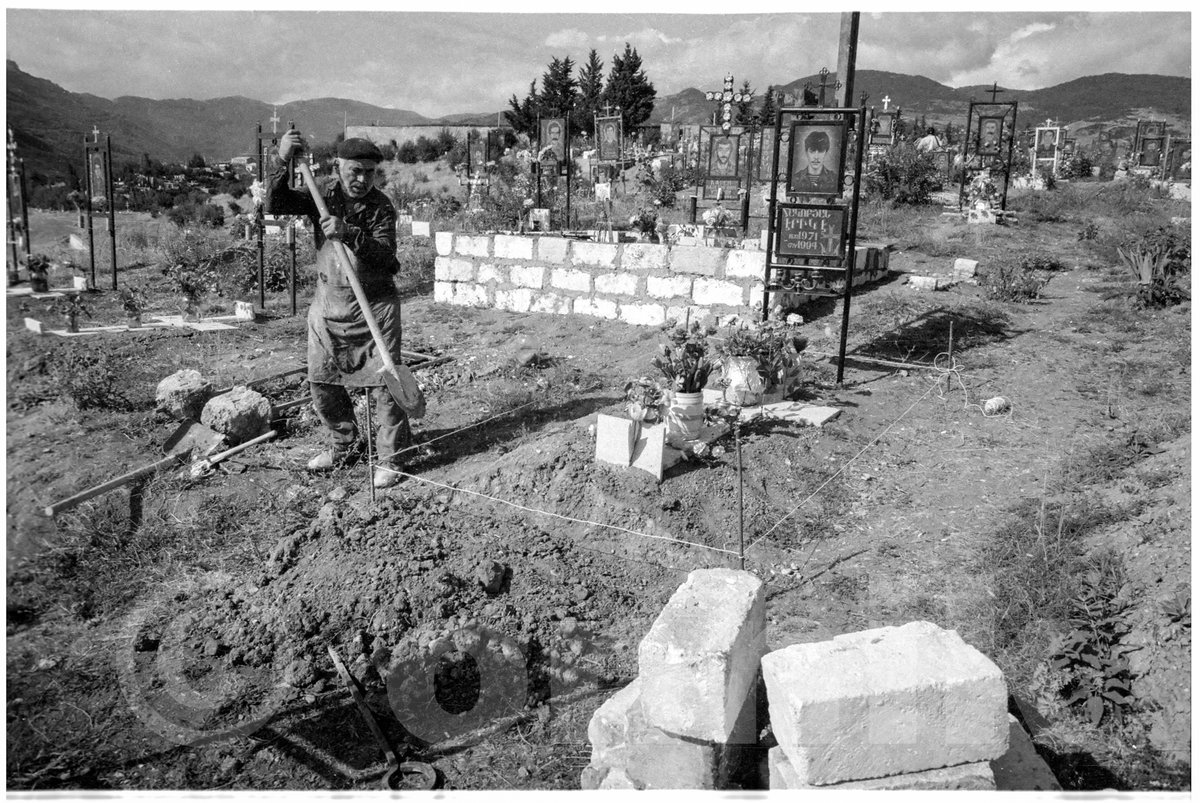

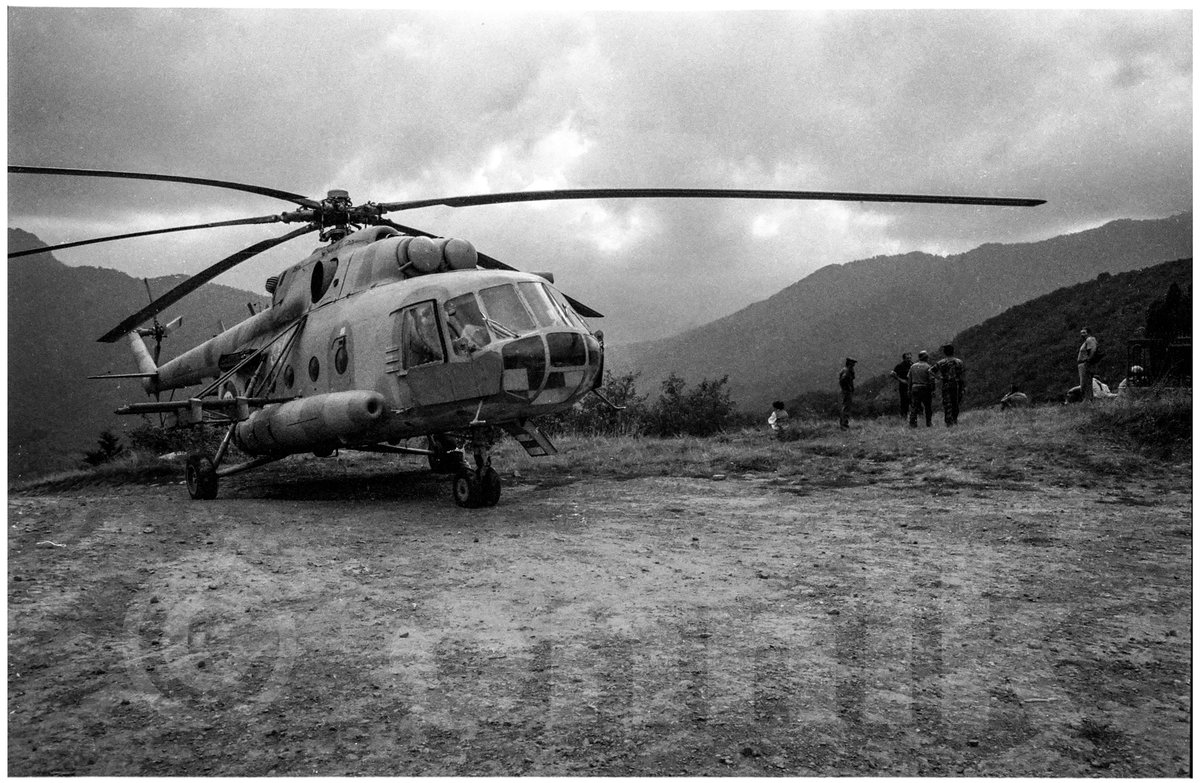

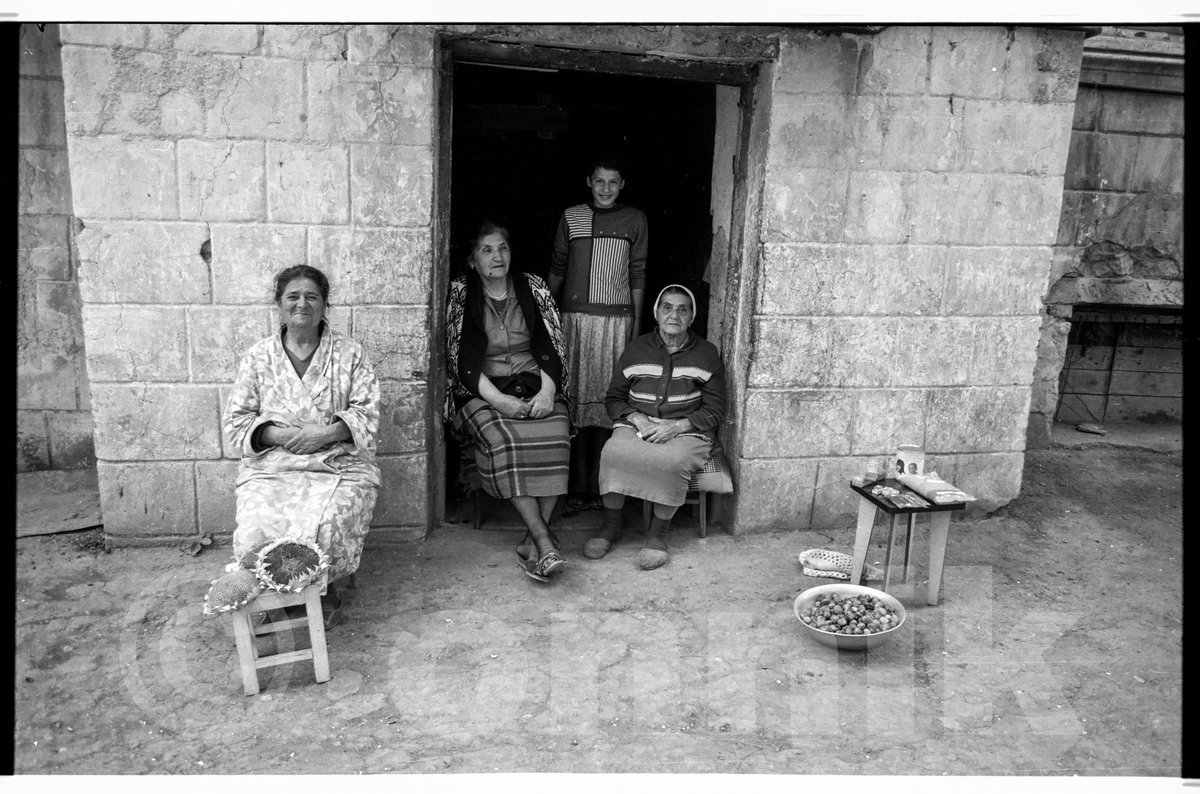

In 1994 I visited Nagorno Karabakh for UK media. On my return to London, some analysts I interviewed said a peace deal would not be signed for 20 years. 26 years later and it still hasn& #39;t. The lack of that deal has led to a resumption of hostilities today. #Armenia #Azerbaijan

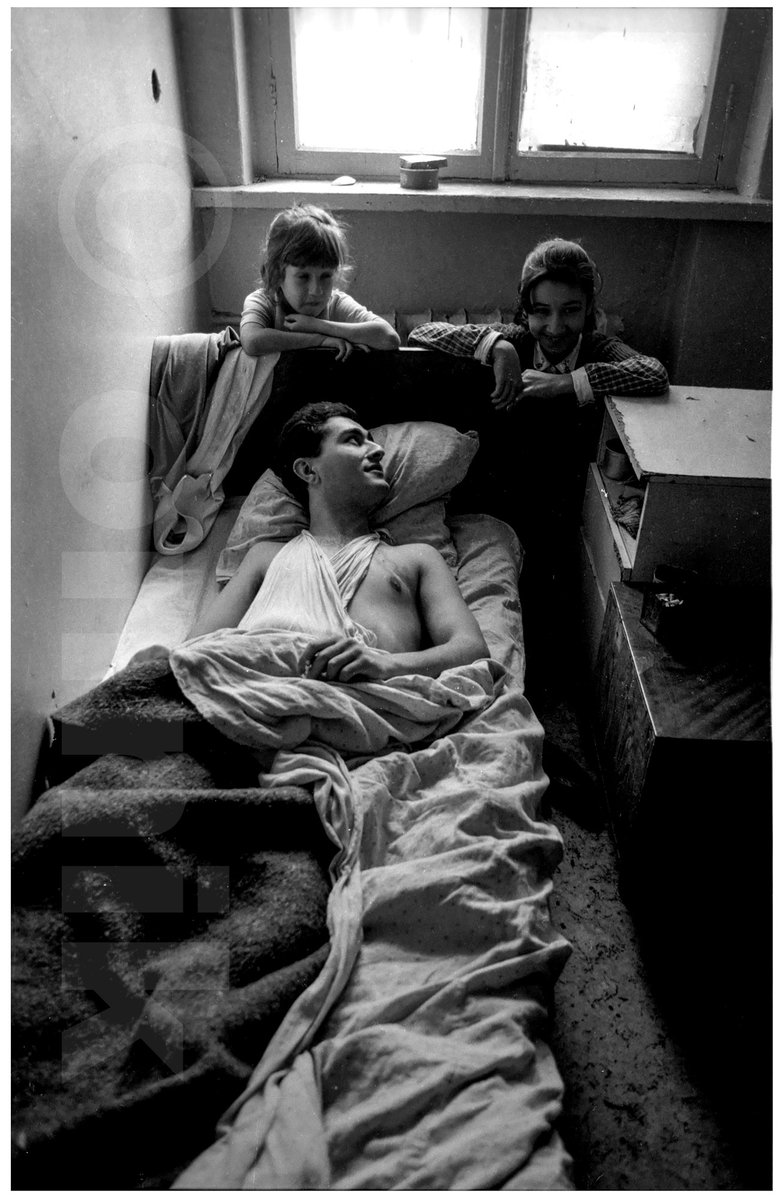

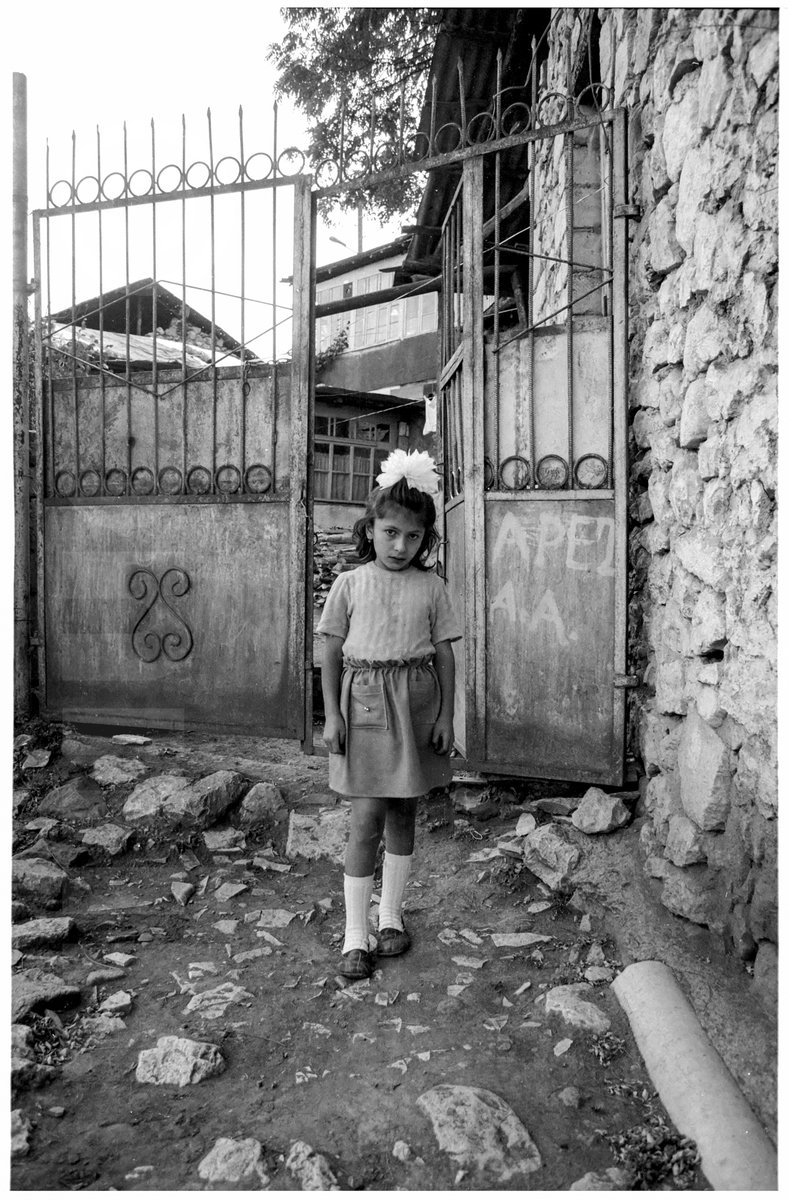

Back then, as I& #39;ve tweeted before, I remember visiting Azerbaijani PoWs and civilian hostages held captive in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh. I remember that the ethnic Armenian and Azeri kids were playing together where they were held. Peace felt closer then than it does now.

Yet, the terms of the 1994 ceasefire, as outlined in the Bishkek Protocol were clear.

– Cessation of hostilities

– Withdrawal of forces in occupied territories

– Restoring communication

– Return of IDPs and Refugees

– Creating peacekeeping force

None of this happened.

– Cessation of hostilities

– Withdrawal of forces in occupied territories

– Restoring communication

– Return of IDPs and Refugees

– Creating peacekeeping force

None of this happened.

Since then, those details form the basis for most peace negotiations, with the addition of elaborating a mechanism to determine the final status of Nagorno Karabakh through a new referendum. But at various times, either Armenia or Azerbaijan have prevented this from happening.

As a result, thousands have died since & #39;94 and incidents between Armenia and Azerbaijan intensify to the situation today. Many point to a lack of political will to resolve the Karabakh conflict but what about civil society? In this thread over the course of today, some comments…

First off, in 1998, when I was offered a contract with an international organisation and moved from London to Yerevan, nobody cared about Karabakh. Poverty and corruption were the main concerns. Kocharian used the conflict to attack the opposition. Civil society was nowhere.

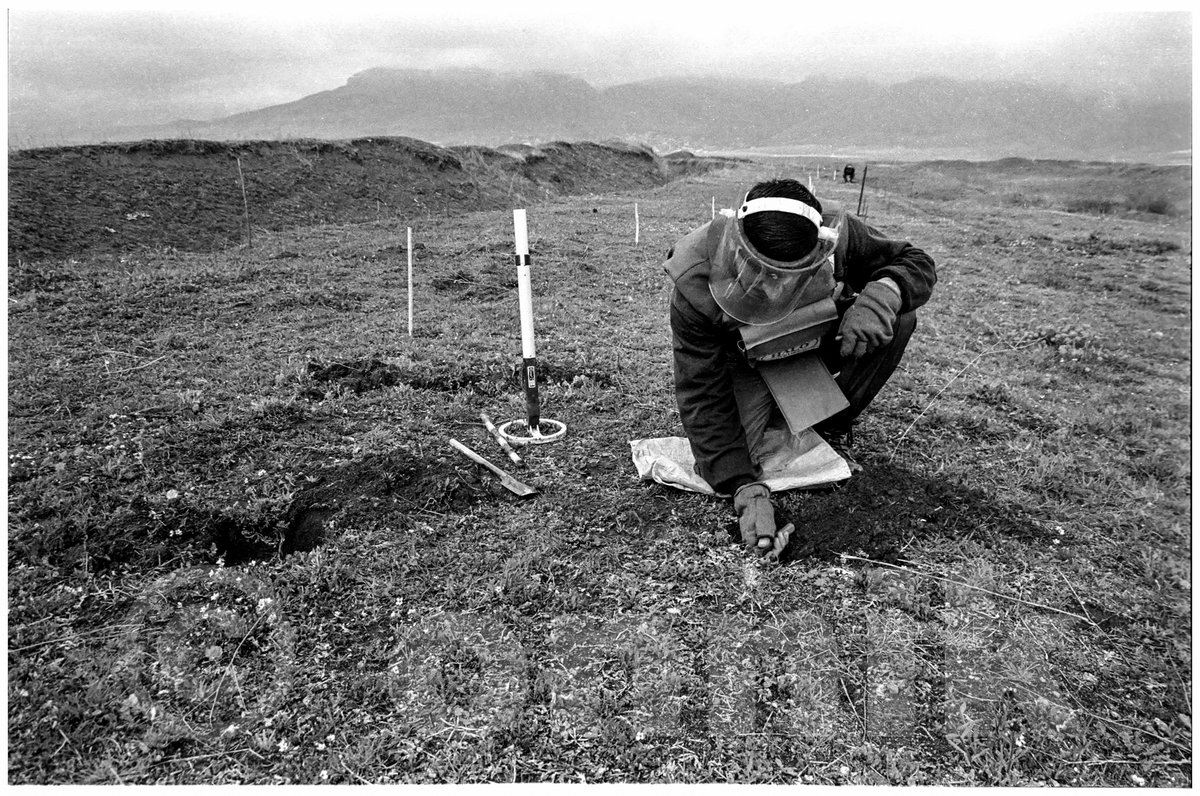

There was exchange of journalists and civil society actors between the two, but it wasn& #39;t very visible. International NGOs, however, were. Minefields were cleared and refugees and Displaced Persons were rehoused. Wasn& #39;t until later that local NGOs became more visible on Karabakh.

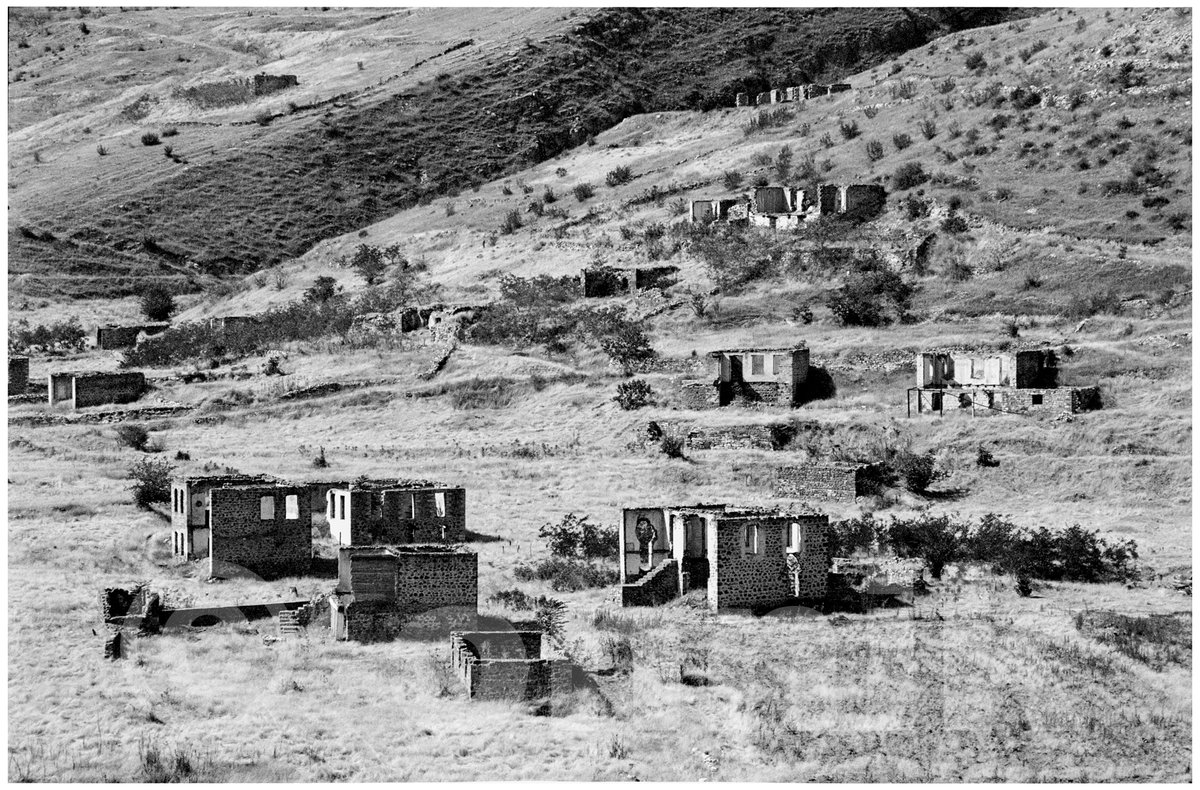

Meanwhile, it became evident that a policy to move Armenian settlers into the regions surrounding Karabakh started to pick up pace. By 2005, the & #39;military buffer zone& #39; was slowly being sold as & #39;liberated.& #39; Many of the new emerging & #39;peace builders& #39; privately held the same view.

Of course, the situation with civil society likely just as bad if not worse in Azerbaijan at that time. Neither side seemed happy with how cross-border meet-ups were. That would change later, but I can only comment on Armenia. For Azerbaijan, follow @HamidaGiyas for commentary.

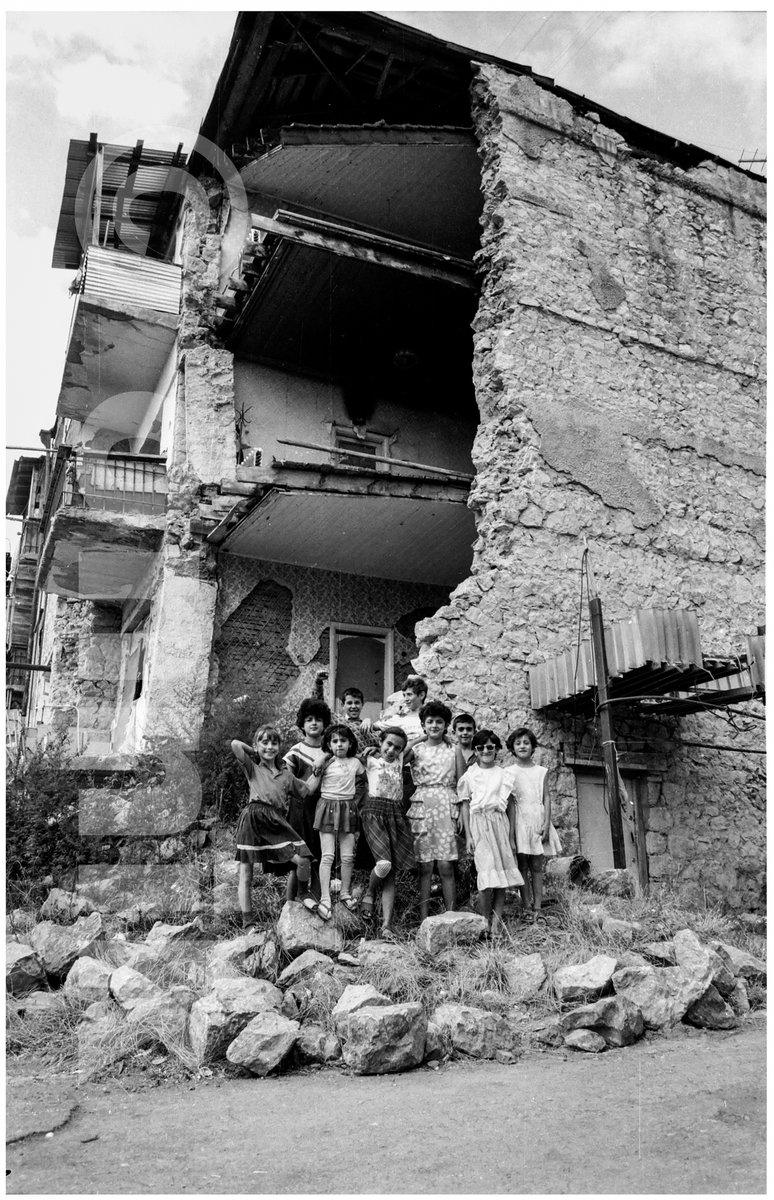

10. Need to number these tweets as the thread will be updated throughout the day so a filler pic in this break.

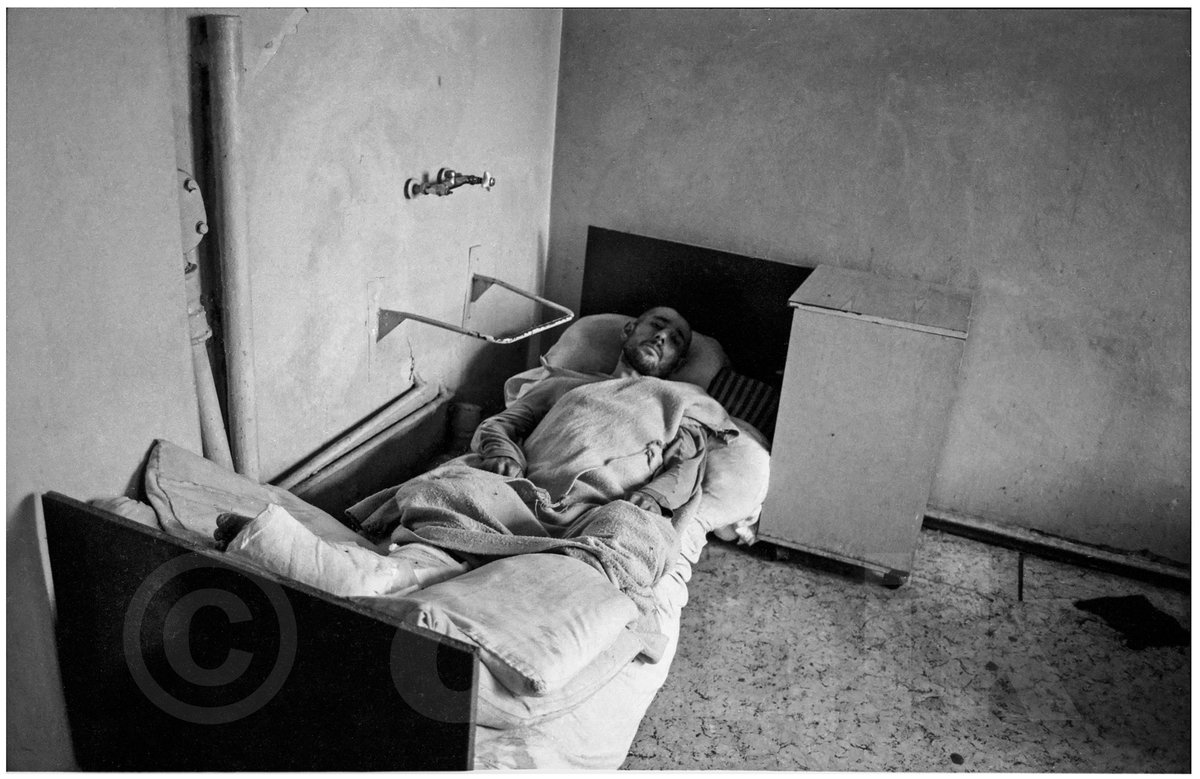

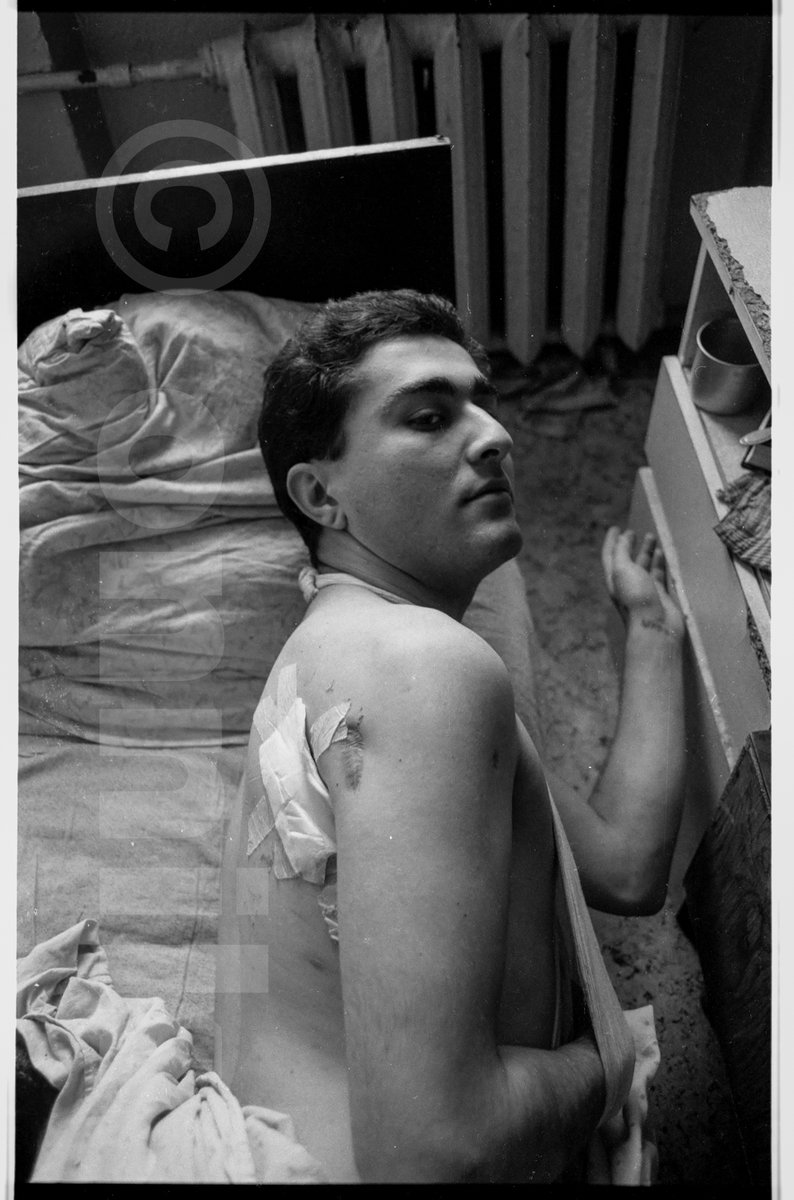

Wounded Azerbaijani PoW in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh 1994. On my return to London I followed up with @AmnestyUK on their fate. Exchanged for Armenian PoWs in 1995

Wounded Azerbaijani PoW in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh 1994. On my return to London I followed up with @AmnestyUK on their fate. Exchanged for Armenian PoWs in 1995

11. Back to civil society. Around 2005 there was another push for peace, but NGOs in Armenia were most open in opposing it, despite the sizeable amount of conflict resolution funding they received from international donors. It seemed they were part of the problem, not a solution

12. Same happened with momentum towards the Armenia-Turkey protocols. Many Armenian NGOs privately opposed it and any attempts to recognise that AM-TR & AM-AZ relations were inexorably linked. Turkey closed its border in 1993 because of the seizure of seven regions outside NKAO.

13. They needn& #39;t have bothered. In the end it was Azerbaijan that prevented the ratification of the protocols, highlighting how Baku considered good Ankara-Yerevan relations to be against its own interest. It also highlighted the nationalism that exists in Armenian civil society.

14. That nationalism was most evident in 2016 when many NGOs supported the & #39;Daredevils of Sassun,& #39; an ultra-nationalist group opposed to Karabakh peace. Prior to this, while Azerbaijan could be considered very aggressive in its tone, Armenia was still actually passive-aggressive.

15. In 2008, working for @globalvoices and frustrated by NGO peace-building initiatives, I journeyed to Tbilisi to reach out to Azerbaijani bloggers at a cross-border event. I remember that Armenian bloggers stood more than 10 meters away from them. I went to speak to them.

16. Went well and we connected on FB. Back in Yerevan, the FB feeds of Armenian and Azerbaijani youth were so similar. Fears, concerns were same, and the emerging youth movement in Baku, now silenced, was impressive. My AZ network multiplied. Why hadn& #39;t Armenian NGOs done this?

17. But Armenian NGOs did notice and asked me for the contacts of these & #39;good Azerbaijanis,& #39; and I think I now know what they meant by that. They didn& #39;t want to find mutual ground. They wanted to persuade the & #39;other& #39; of why the Armenian position was correct and theirs was wrong.

18. Perhaps the same was true for the Azerbaijani side too, but they didn& #39;t so openly articulate it as their Armenian counterparts. Despite the official rhetoric from Baku I found them eager to meet Armenians. True, most were opposition youth, but so too were the Armenian side.

19. I also started to date someone from Azerbaijan (meeting up in Tbilisi) which, while it didn& #39;t result in any attacks on me in Yerevan, was used by & #39;peace builders& #39; to discredit my work on conflict-resolution. In 2012 we respectively left Yerevan and Baku for Tbilisi.

20. To clarify, this was my experience with the Armenian NGO sector. Similar criticisms can be made of its equivalent in Azerbaijan too. Again, I point you in the direction of an Azerbaijani tweep. More to say on what civil society needs to do, but later. https://twitter.com/HamidaGiyas/status/1313409316179726337">https://twitter.com/HamidaGiy...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter