Robert Gordon& #39;s *The Rise and Fall of American Growth* is one of the key texts that established the “stagnation” hypothesis. It& #39;s also a tome, weighing in at over 800 pages.

I read the whole thing so you don& #39;t have to: https://twitter.com/rootsofprogress/status/1313230296360259584">https://twitter.com/rootsofpr...

I read the whole thing so you don& #39;t have to: https://twitter.com/rootsofprogress/status/1313230296360259584">https://twitter.com/rootsofpr...

Most of the book is a survey of American living standards and how they have changed over the last ~150 years. Gordon argues that the period 1870–1970 was a “special century” of growth, not to be repeated.

First, he shows that life was utterly transformed for the better 1870–1940, across the board, with improvements continuing at a slower pace until 1970.

Since 1970, information & communication technology has been similarly transformed, but other areas of life have not been.

Since 1970, information & communication technology has been similarly transformed, but other areas of life have not been.

Examples:

• Food: monotonous diet of easily-preserved foods such as pork & cornmeal → more varied diet thanks to refrigerators & premade foods

• Clothing: women making clothes at home → buying outfits in department stores

• Food: monotonous diet of easily-preserved foods such as pork & cornmeal → more varied diet thanks to refrigerators & premade foods

• Clothing: women making clothes at home → buying outfits in department stores

Examples (2):

• Retail: a single town general store → department stores & mail-order

• The home: isolated, cold & dirty → “networked” with water, sewage, gas, electricity & telephone

• Transportation: horses & trains → automobiles & electric streetcars, then planes

• Retail: a single town general store → department stores & mail-order

• The home: isolated, cold & dirty → “networked” with water, sewage, gas, electricity & telephone

• Transportation: horses & trains → automobiles & electric streetcars, then planes

Examples (3):

• Communications: mail & telegrams → telephone, radio & TV

• Health: disease common → water treatment, pasteurization, safety & purity standards for food & drug

• Work: dangerous & uncomfortable manual labor on farms → better jobs in factories & offices

• Communications: mail & telegrams → telephone, radio & TV

• Health: disease common → water treatment, pasteurization, safety & purity standards for food & drug

• Work: dangerous & uncomfortable manual labor on farms → better jobs in factories & offices

But all of the above was in place by 1970, and most of it by 1940. Other than information/computing, there has been only minor and incremental progress in most of these areas (the biggest inventions have been microwaves and air conditioning).

Information & communication technology is the exception: the one area where revolutionary progress has been made since 1970, with major advances in electronic devices, and of course computers and the Internet.

But this is only one industry. 1870–1970 revolutionized *everything*.

But this is only one industry. 1870–1970 revolutionized *everything*.

Gordon doesn& #39;t deny that electronics, computers and the Internet were a revolution in their own right with transformative benefits.

But the 1870–1970 period saw *multiple* such revolutions, not only one.

But the 1870–1970 period saw *multiple* such revolutions, not only one.

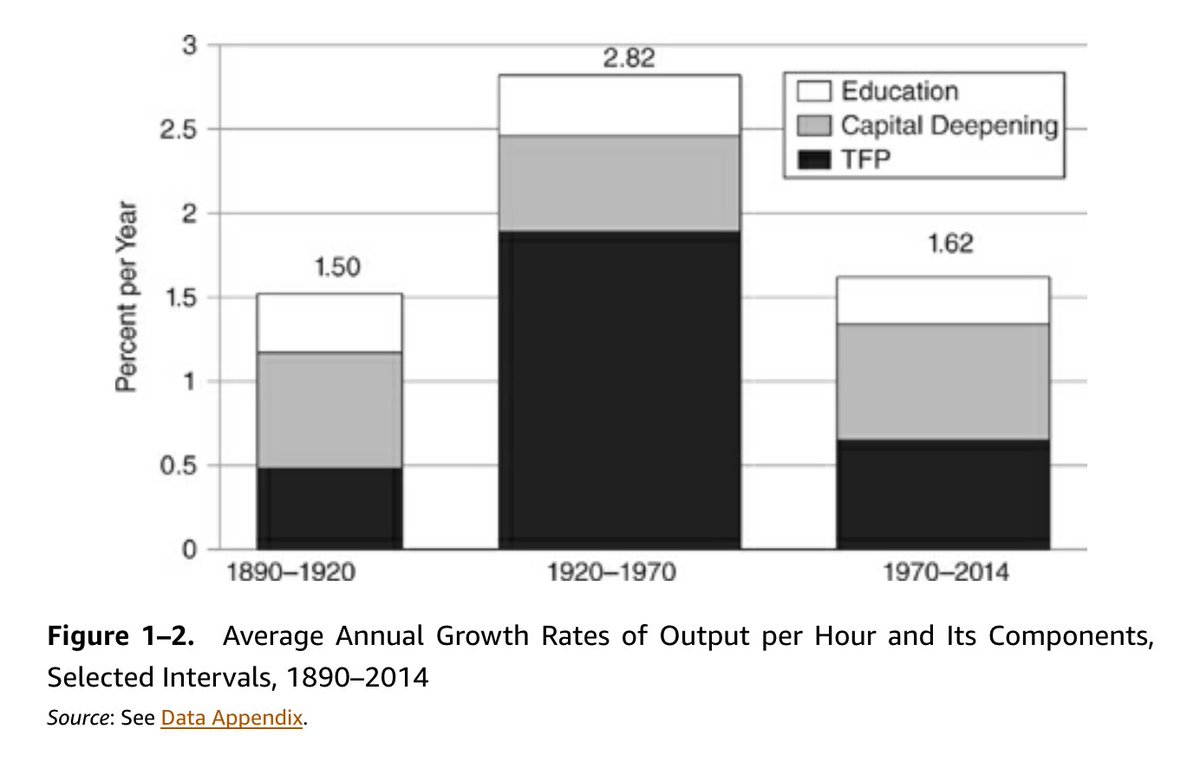

All of this narrative is backed up with data. Here are GDP growth rates, split into three periods. The 1920–70 period stands out as having significantly higher growth than either before or after:

Many critics of Gordon argue that GDP doesn& #39;t capture all of consumer welfare. Many technologies have vast consumer surplus: Google, Wikipedia & YouTube are free.

Gordon agrees, but argues that this has *always* been the case, so mismeasurement does not explain the trend.

Gordon agrees, but argues that this has *always* been the case, so mismeasurement does not explain the trend.

In fact, Gordon argues that GDP was perhaps *more* of an underestimate of consumer welfare in the past: think of the value of free radio and television programs, the liberation provided by the automobile, or the lives saved by penicillin.

So what about the future? Gordon is, to my mind, surprisingly pessimistic. He thinks that the 20th-century trends creating high growth have played out, and now they& #39;re simply over. All the big inventions are already deployed. Everyone already has a car, a phone, and a toilet.

He also sees positive demographic trends as played out: high school graduation rates, the urban migration, entry of women into the workforce. These gave the 20th century a boost, but they& #39;re not going much further.

To add to this, he lists “headwinds” working against growth: the boomers are retiring, debt is rising (both student debt and government debt), inequality is growing (and thus gains in GDP per capita will translate to smaller gains in median income).

His forecast: 0.3% annual growth in real median disposable income per person over the period 2015–2040, compared to 2.25% growth 1920–70 and 1.46% 1970–2014.

Can we do anything about it? He lists several prescriptions, including tax reform, regulatory reform, more immigration, drug legalization, and more public school from preschool through university.

However, these are only palliative.

However, these are only palliative.

Fundamentally, he sees the slowdown as so natural/inevitable that it is not even to be lamented: “American growth slowed down after 1970 not because inventors had lost their spark… but because the basic elements of a modern standard of living had by then already been achieved.”

I think the book is very valuable and any serious student of progress should read it. It& #39;s a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative survey of 150 years of American innovation. It really illustrates the dramatic improvement in living standards.

But I find Gordon’s vision for the future strangely lacking in imagination, and his complacent acceptance of low growth disappointing.

Contrast this with Peter Thiel, whose view seems to be that we dropped the ball, and that we should have had flying cars by now.

Contrast this with Peter Thiel, whose view seems to be that we dropped the ball, and that we should have had flying cars by now.

It& #39;s bizarre to me that after almost 700 pages of describing breakthrough innovations, Gordon thinks that there are no more breakthroughs left! Even the scant few he considers, he assesses only based on their current state, not future potential.

But I still find value in his prediction if taken, not as a prophecy, but as a warning. A 0.3% growth rate *is* the future—*if* we have no more breakthroughs.

We have, in some ways, been coasting on the achievements of the past. Restoring high growth will require new fundamental inventions and possibly entire new fields of science. I’m becoming increasingly convinced that this is where progress studies should focus.

More detail and charts in the full review: https://rootsofprogress.org/summary-the-rise-and-fall-of-american-growth">https://rootsofprogress.org/summary-t...

And subscribe to @rootsofprogress for more like this: https://rootsofprogress.org/subscribe ">https://rootsofprogress.org/subscribe...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter