A lazy Sunday morning, so a thread on one of my favorite pre-Islamic poems, the famous poem of praise by al-Nābigha to the Ghassānid king ʿAmr. 1/

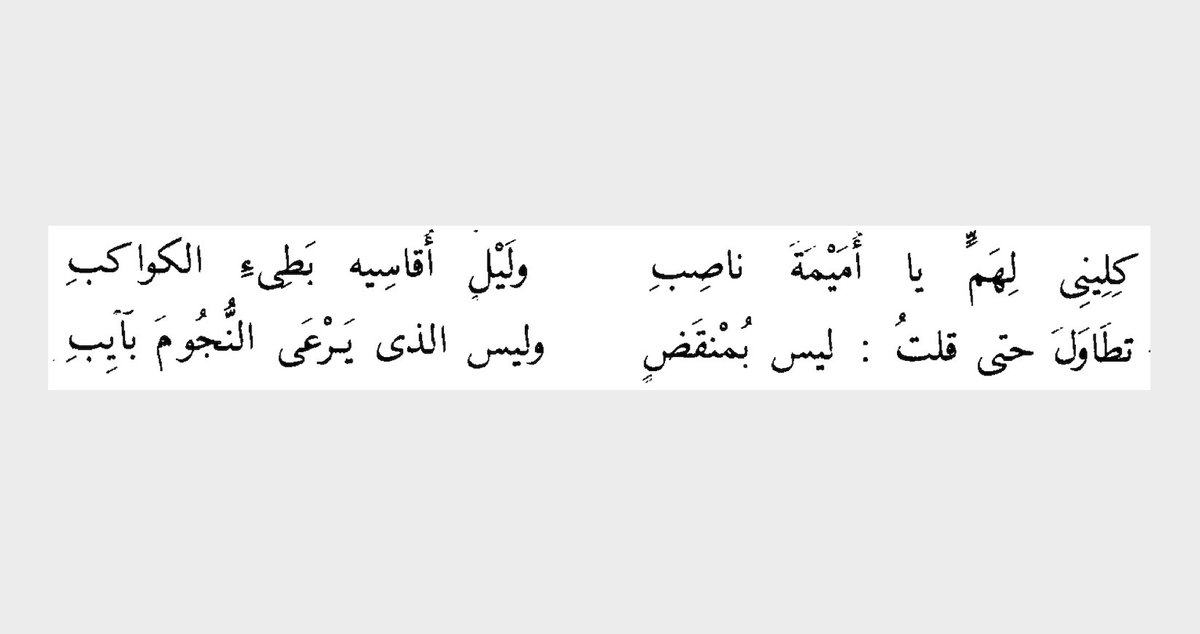

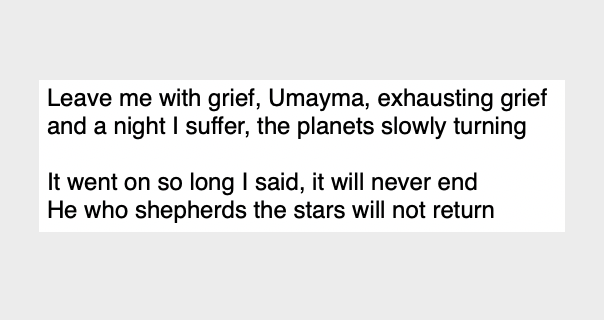

The opening evokes forlorn love with the wonderful image of the speaker sitting under the stars, contemplating their endless orbit. (my translation) 2/

The second line, typically elliptical, conjures the isolation of a shepherd charged with looking after the stars - he, unlike a shepherd with a traditional flock, cannot return to the comforts of home at night. 3/

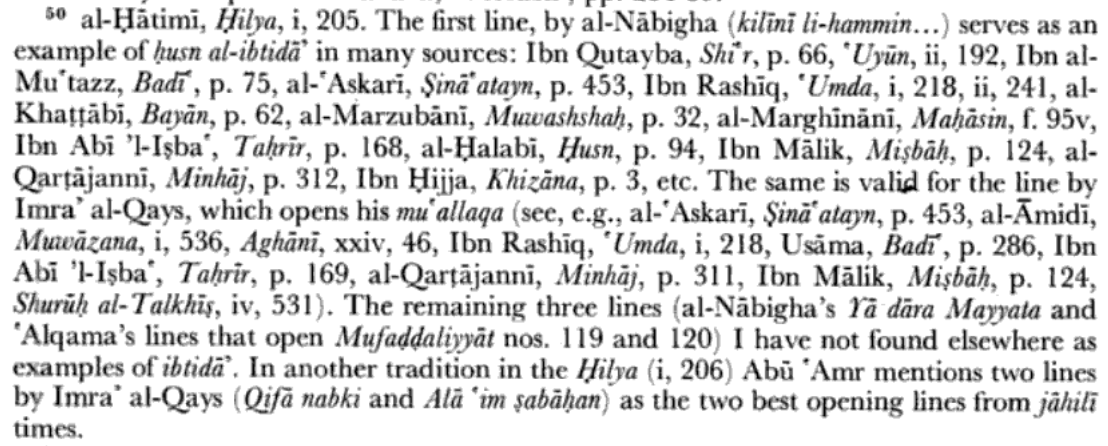

I& #39;m not alone in finding these lines captivating; the medieval literary critics frequently cited them for their skill in opening the poem (below from van Gelder& #39;s Beyond the Line) 4/

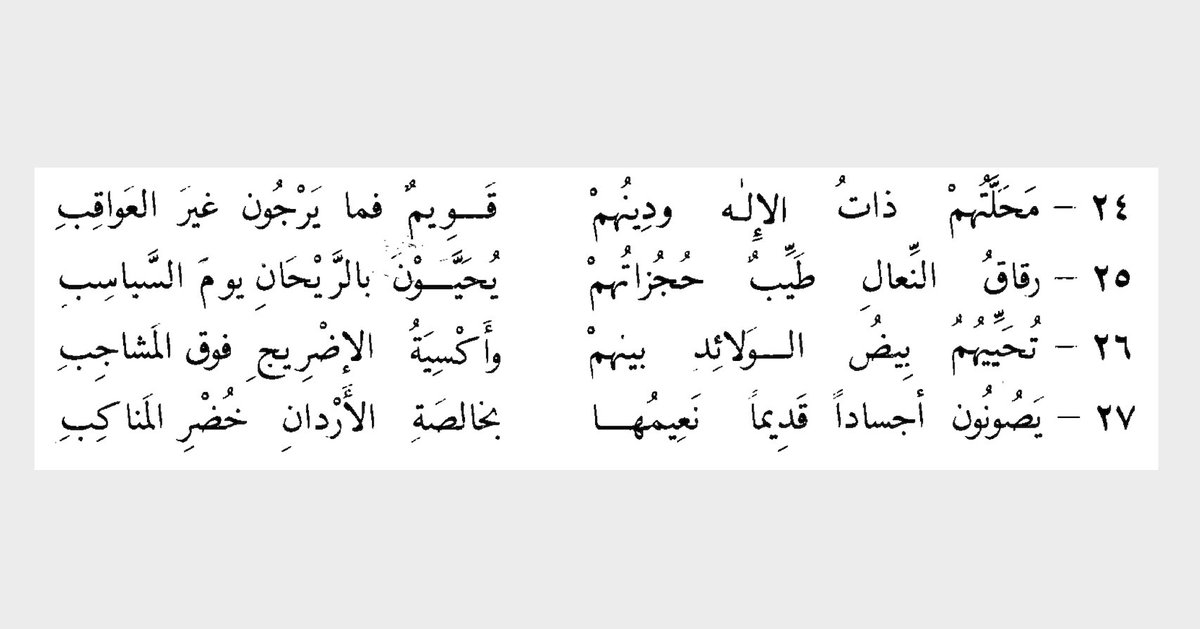

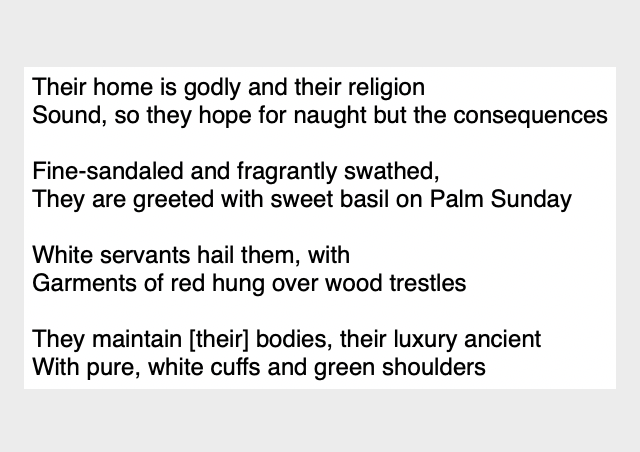

The poem is also famous for its references to religion, specifically to the faith of the Ghassānids, and to clothing. 5/

The Arabic of the first line (محلّتهم ذات الإله) has been interpreted a number of different ways, including as an oblique reference to Jerusalem (بيت المقدس) - elsewhere the poem refers to a Syrian setting) 6/

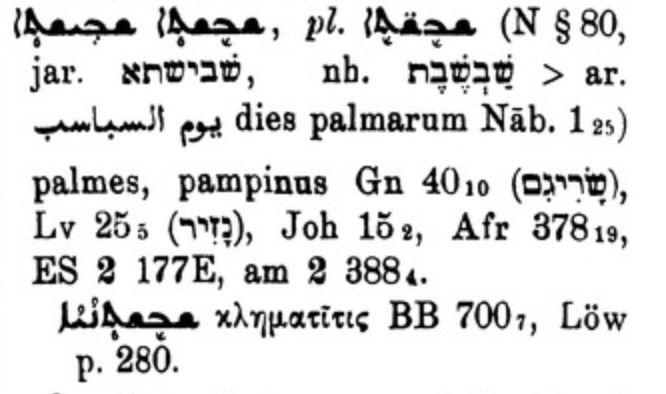

The words for Palm Sunday, يوم السباسب, have their echo in Syriac (below from Brockelmann& #39;s Lexicon Syriacum) 8/

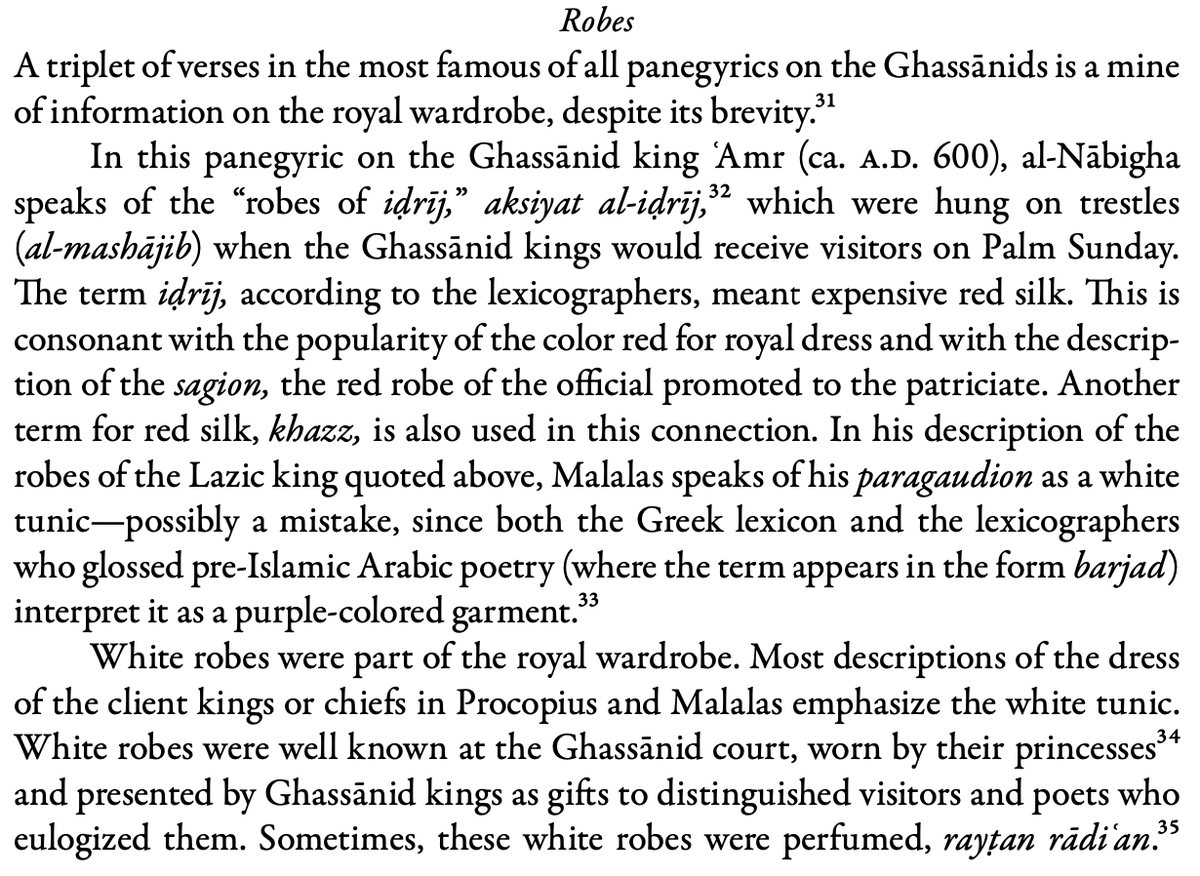

The issue of the references to textiles have been discussed by Irfan Shahid in Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century 9/

A possibility mentioned by some commentators is that the & #39;green& #39; (خضر) referred to in the poem is not green but black, and that rather than shoulders we should translate & #39;flanks,& #39; as a reference to the stains left by the royals& #39; weapons. 10/

A final thought for the morning: an eternal question about the corpus of pre-Islamic poetry is about its authenticity. Often references to Christian ceremonies or Qurʾānic echoes are taken to indicate anachronism. 11/

And that is certainly possible! But the problem is difficult to settle: are such references a confirmation of the cultural milieu of the Qurʾān or back projections? 12/

Two lines (at least!) stand out to me from this poem for their echoes into later culture. The first, already translated, is فما يرجون غير العواقب. One can also take رجو in the sense of & #39;to fear& #39; 13/

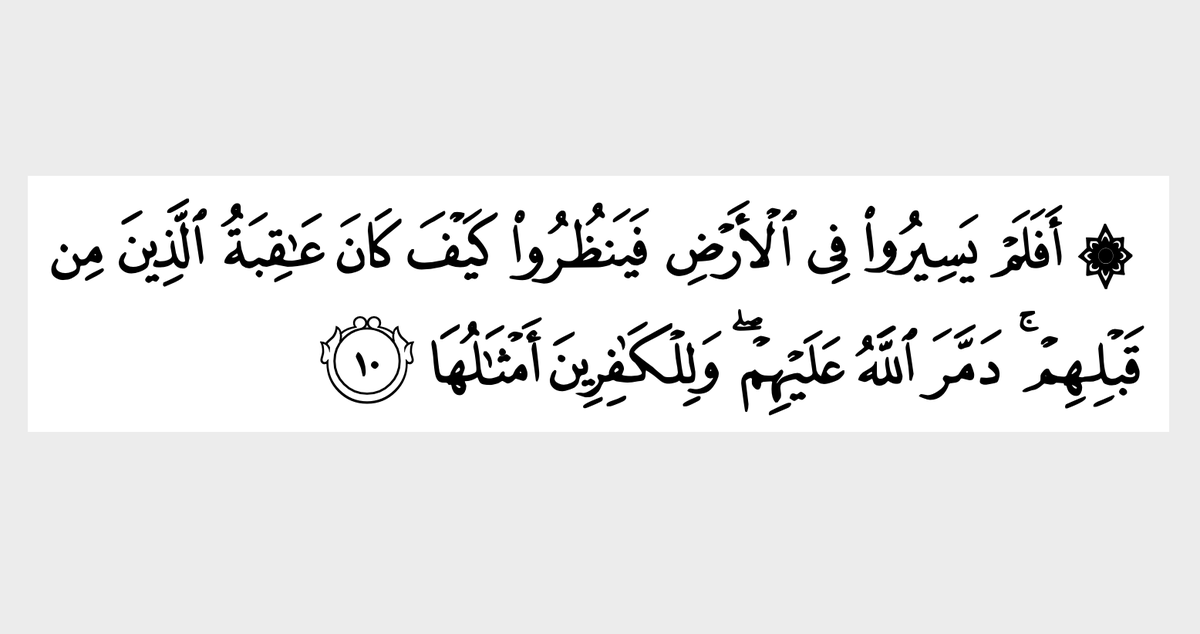

I.e., & #39;they fear only the consequences / [final] outcome.& #39; The noun here, in the singular عاقبة, appears 32 times in the Qurʾān, typically in reference to eschatological fate. 14/

For example, Q Muḥammad 47:10: "Have they not travelled the earth to see the عاقبة of those before them? God destroyed them, and the unbelievers will have the same." 15/

The second line we might translate as & #39;I swore an oath without exception / Knowing nothing beyond [my] good opinion of [my] companion& #39; 16/

This is interesting, because of the importance of the concept of & #39;good opinion& #39; (ḥusn al-ẓann) in the later Arabo-Islamic tradition. 17/

I do not know the complete early history of ḥusn al-ẓann; we do know that it - or rather, ḥusn al-ẓann bi-Llāh - was the topic of a ḥadīth collection by Ibn Abī al-Dunyā (d. 281/894). 18/

How to take these resonances, as historians? I don& #39;t have a firm answer, although I think it is clear that the extremes of pre-Islamic poetry being entirely fabricated, or it being entirely authentic, are equally unsustainable. 19/

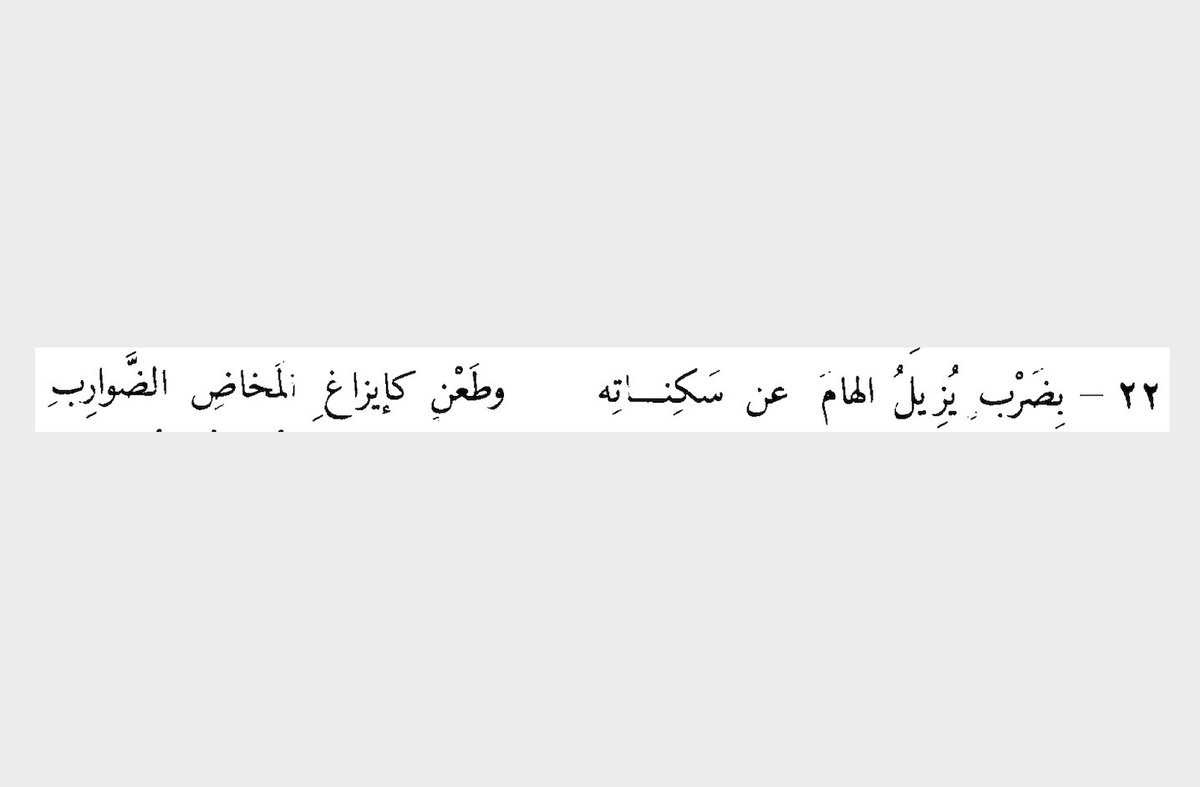

Lastly, and in homage to @tafsirdoctor& #39;s translation challenge, I& #39;ll end with the below for anyone who thinks they can render it as accurately, and elegantly, as possible! (It& #39;s a good demonstration of the, well, unique ethic of pre-Islamic poetry.) 20/end

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![The second line we might translate as & #39;I swore an oath without exception / Knowing nothing beyond [my] good opinion of [my] companion& #39; 16/ The second line we might translate as & #39;I swore an oath without exception / Knowing nothing beyond [my] good opinion of [my] companion& #39; 16/](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EjfggKCXcAQirTO.jpg)