Day 2! Today we& #39;ll be talking about Pilot Officer Johnny Smythe (RAF Volunteer Reserve). Born in 1915, Smythe joined the RAF in 1940. After Navigation Training he joined No.623 Squadron in 1943.

In the 18th November he took part in a Diversionary raid over Mannheim as one of Seven Short Stirling& #39;s Assigned from the Squadron. Symthes Stirling was hit and he was forced to bale out.

Smythe landed safely and hid in a barn until he captured - his own account of this is far better than I can tell it.

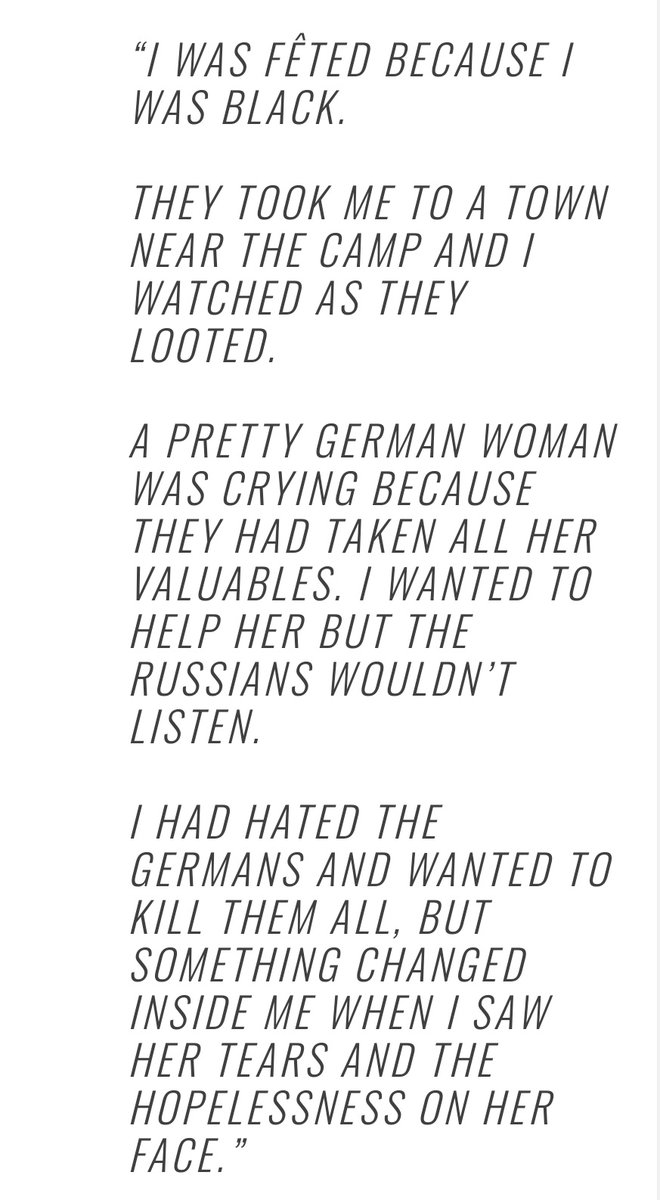

Smythe was sent to Stalag Luft I. He became a member of the escape committee, even though he admitted "a 6ft4 black man wouldn& #39;t get far in Pomerania". he said of it,"We were all just prisoners together. It wasn& #39;t until I looked in the mirror that I remembered that I was black."

One day in 1945 they woke up to discover all the German guards had dissapeared. The Russians soon arrived, and he was free. He then got to see the devastation the Russians inflicted on the German population.

After the War, Smythe (along with many other Servicemen, including Trinidadian Ulric Cross) were consulted by Whitehall over whether West Indian workers who returned to their homes should be allowed to come back to the UK. He said yes, and so the Empire Windrush sailed.

Smythe trained as a Lawyer after the war and rose to become the Attorney General of Sierra Leone. In this capacity he attended a party at the British Ambassador& #39;s house, and ended up discussing his war experience with the German Ambassador, who had also been a pilot.

"When told about the date and place that Johnny was shot down, the ambassador turned pale: ‘My god Johnny, I got my first kill on that day, I shot down a British bomber.’ They put their arms around each other and were almost in tears" - quoted from Eddy Smythe

Sources https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/sierra-leone-stalag-luft-i-remembering-johnny-smythe">https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/...

Day 3 of #BlackHistoryMonth  https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> Military History posts! Today we& #39;re going to jump back from 1943 to 1776 to talk about the Black Loyalists in the American War of Independence

https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> Military History posts! Today we& #39;re going to jump back from 1943 to 1776 to talk about the Black Loyalists in the American War of Independence

#blackhistorymonthuk https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt="">

https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt="">

#BlackLivesMatterUK

#blackhistorymonthuk

#BlackLivesMatterUK

As tensions began to heat up between the colonists and the crown in the 1770s, many American slaves began to believe that supporting George III would be their key to freedom. Slaveowners began to fear that the crown would organise a slave revolt in their backyard

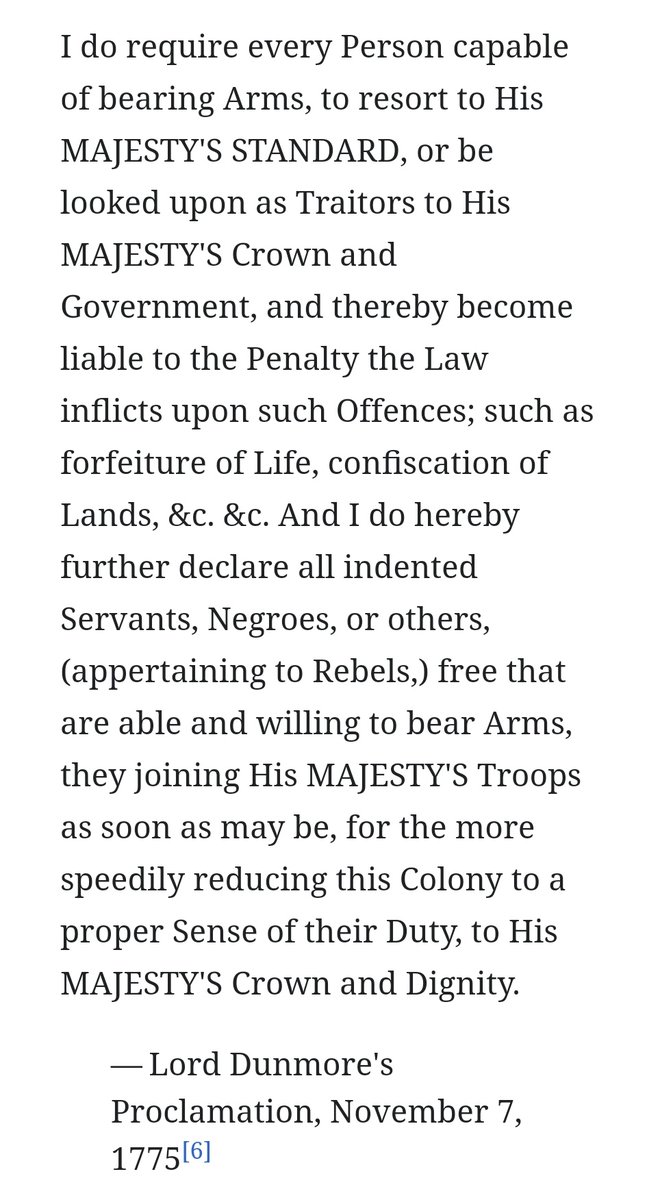

This was something that lord Dunmore (last governor general of Virginia) took advantage of. In November 1775, he issued this statement promising freedom for service in the British Army.

Within weeks over 800 slaves had fled their owners and joined Dunmore in Norfolk, Virginia, despite their masters telling them the British would simply sell them into slavery in the West Indies

Once the war began in earnest, British leaders made serious movements towards mass emancipation for enlistment in order to bolster the ranks of the beleaguered British Forces in America. However, the arrival of 30,000 Hessian Mercenaries meant many plans were shelved.

While free coloured men were no longer needed to fill the ranks, the economic value of runaways was still important. In 1779 Sir Henry Clinton (CinC North America) issued the Phillipsburg proclamation, promising freedom to any slave who left their Patriot Master.

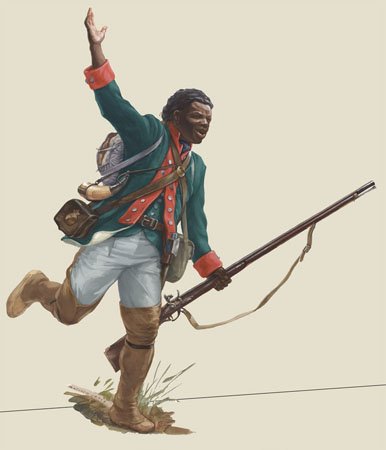

Several Black Regiments (really only about company sized) were formed during the war, such as the Ethiopian Regiment, the Black Company of Pioneers, The Jersey Shore Rangers, the Mosquito Shore Rangers, and the Black Dragoons of the South Carolina Royalists.

The common battlefield role of black soldiers (as it would be in western, depressingly right up until the end of ww2) was labour and pioneer work, but many also served as local scouts and irregulars, guiding British Troops through unfamiliar territory

When the war ended, the issue of Black troops was a soft spot for both Loyalist and Patriots (who both wanted their slaves back). Slavers trawled through towns in the chaos of the Loyalist evacuation, taking escaped slaves and free blacks into bondage without punishment

Washington himself ordered all runaway slaves to be returned under the the Terms of the Treaty of Paris, but the British put their foot down.

A compromise was made where the British paid owners compensation, and thus 3,000 black loyalists were transported to Nova Scotia.

A compromise was made where the British paid owners compensation, and thus 3,000 black loyalists were transported to Nova Scotia.

They settled on (very marginal) land given to them by the British Government - the largest settlement, Birchtown, was for a while the largest free black Community in North America. There were difficulties - in 1784, they suffered the first race riot in Canadian History

And in 1792, when offered the opportunity to settle in Sierra Leone, 1200 Loyalist took the offer and founded Freetown, starting a new chapter in their history.

There is still a significant black population in Nova Scotia descended from free blacks and runaways who arrived there throughout the 18th and 19th century. They had to fight for their rights, their land and their dignity. But that is a different story.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

Military History posts! Today we& #39;re going to jump back from 1943 to 1776 to talk about the Black Loyalists in the American War of Independence #blackhistorymonthuk https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> #BlackLivesMatterUK" title="Day 3 of #BlackHistoryMonth https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> Military History posts! Today we& #39;re going to jump back from 1943 to 1776 to talk about the Black Loyalists in the American War of Independence #blackhistorymonthuk https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> #BlackLivesMatterUK" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

Military History posts! Today we& #39;re going to jump back from 1943 to 1776 to talk about the Black Loyalists in the American War of Independence #blackhistorymonthuk https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> #BlackLivesMatterUK" title="Day 3 of #BlackHistoryMonth https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> Military History posts! Today we& #39;re going to jump back from 1943 to 1776 to talk about the Black Loyalists in the American War of Independence #blackhistorymonthuk https://abs.twimg.com/hashflags... draggable="false" alt=""> #BlackLivesMatterUK" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>