BLACK HISTORY MONTH - 1 MONTH, 31 STORIES

Black History Month means many things to different people. For some, it’s a celebration that marks the many accomplishments Black people have made in Britain. For others, it’s a reminder that Black history *is* history, and

(1/3)

Black History Month means many things to different people. For some, it’s a celebration that marks the many accomplishments Black people have made in Britain. For others, it’s a reminder that Black history *is* history, and

(1/3)

one that cannot be viewed in isolation to wider social, political and cultural movements happened at any given time.

Truth be told, it’s all of these things which is why we have decided to mark Black History Month by focusing on 31 stories

(2/3)

Truth be told, it’s all of these things which is why we have decided to mark Black History Month by focusing on 31 stories

(2/3)

that covers the broad nature of the Black British experience.

We’ll be covering stories of Black abolitionists, the Mangrove Nine to groups who campaigned against institutional racism.

(3/3)

We’ll be covering stories of Black abolitionists, the Mangrove Nine to groups who campaigned against institutional racism.

(3/3)

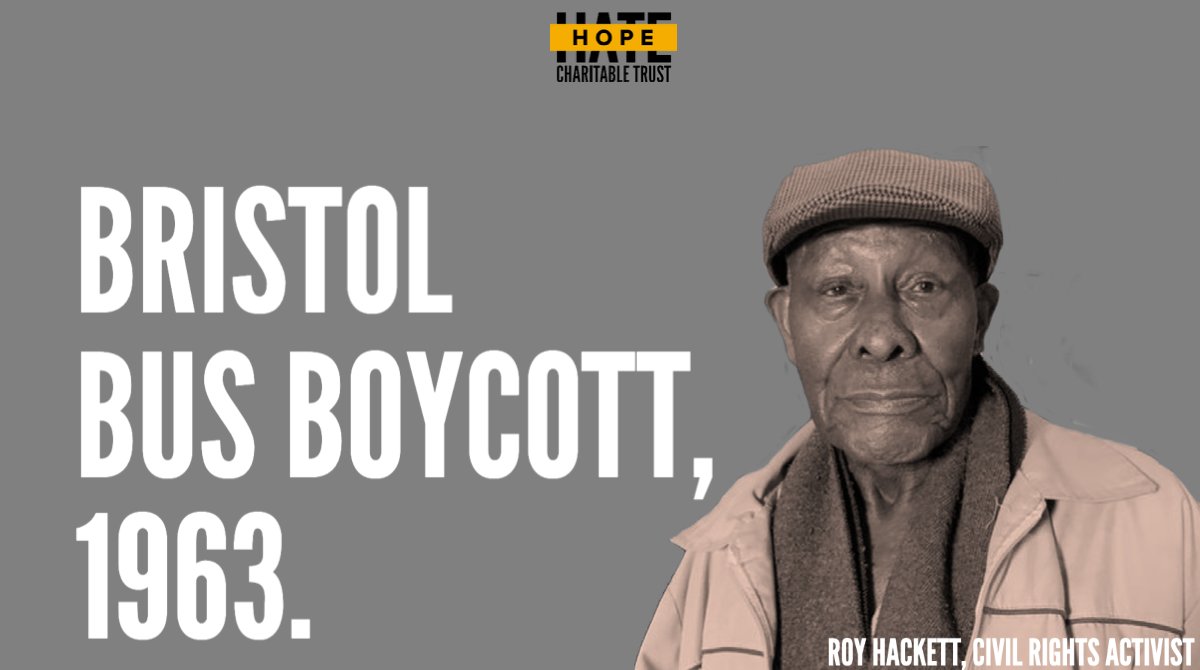

DAY 2: We’ve all heard of the Montgomery Bus Boycott that was sparked by Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat to a white man, but did you know a similar boycott took place on British soil?

The Bristol Bus Boycott (1963) was the result of Paul Stephenson, Roy Hackett and the West Indian Development Council protesting against Bristol Omnibus Company’s refusal to employ Black people as bus drivers.

Black people were turned down en masse despite a reported shortage of bus drivers at the time.

The boycott consisted of a series of protests that involved marching through the streets of Bristol. Black people across Bristol took part in the march, alongside their children...

The boycott consisted of a series of protests that involved marching through the streets of Bristol. Black people across Bristol took part in the march, alongside their children...

university students and some allies who sympathised with their cause.

The campaign soon garnered the attention of the nation where people across the UK saw images of people standing in front of buses and blockading bus stations.

The campaign soon garnered the attention of the nation where people across the UK saw images of people standing in front of buses and blockading bus stations.

It took 4 months for the Bristol Omnibus Company to lift the ban, finally announcing that Black people can work as bus drivers for the organisation.

INTERESTING FACT: The Bristol Bus Boycott took place on the same day Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” speech.

INTERESTING FACT: The Bristol Bus Boycott took place on the same day Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” speech.

DAY 3: Olive Morris (1952-1979) doesn’t get enough credit for her community activism work, and her role in campaigning for racial, gender and squatters’ rights.

You can read about her politics and legacies on our IG page

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⤵️" title="Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⤵️" title="Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten">

https://www.instagram.com/hopenothatecommunity/">https://www.instagram.com/hopenotha...

You can read about her politics and legacies on our IG page

https://www.instagram.com/hopenothatecommunity/">https://www.instagram.com/hopenotha...

DAY 4: We need to talk about people who are making history and cementing their legacies now, and @MunroeBergdorf is one of those people.

Berfdorf is an unapologetically Black Trans woman who uses her platform to advocate for inclusivity for marginalised & minoritised groups.

Berfdorf is an unapologetically Black Trans woman who uses her platform to advocate for inclusivity for marginalised & minoritised groups.

DAY 5: We need to celebrate another person who’s making history in our lifetime.

Lady Phyll is a prominent LGBTQIA+ rights activist and anti-racism campaigner who is actively seeking to dismantle the structures that upholds discrimination against LGBT individuals globally.

Lady Phyll is a prominent LGBTQIA+ rights activist and anti-racism campaigner who is actively seeking to dismantle the structures that upholds discrimination against LGBT individuals globally.

As one of the co-founders of UK Black Pride - Europe’s largest celebration for African, Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American and Caribbean-heritage LGBTQ people - Lady Phyll has created a safe environment for Black queer folks to be themselves. https://bit.ly/3jxecxT ">https://bit.ly/3jxecxT&q...

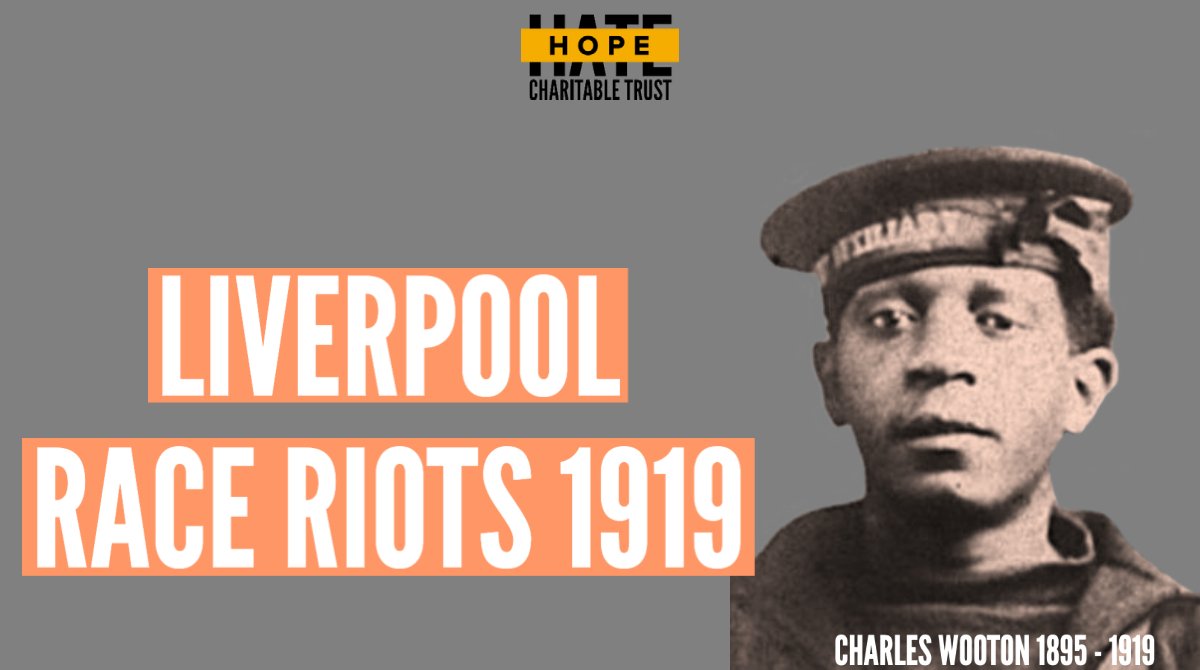

DAY 6: It’s easy to talk about individuals who have “broken barriers” as if they weren’t constructed to maintain oppressive systems of governance during BHM so today, we’ll be focusing on an event that is seldom taught or brought up when reflecting on race relations in Britain.

The 1919 Race Riots that took place in London, Liverpool, Cardiff, Hull and other port cities across the UK was the result of competition for jobs, and White Britons who resented the growing presence of Black labourers in the job market.

This was evident in Liverpool as the city’s Black population increased dramatically during WW1, where they filled the labour shortage. White Britons refused to work alongside Black people - a decision that was backed by trade unions.

The anti-Black hostility became violent.

The anti-Black hostility became violent.

The murder of Charles Wootton, a 24 year old Seafarer from Bermuda, marked the beginning of violent attacks against Black people in Liverpool. Wooton’s house was raided by the police on 5th June 1919 and this culminated in an angry mob chasing him into the River Mersey.

Wooton was pelted with stones until he drowned. Further attacks included houses occupied by Black people bring ransacked and set alight, whereas others were attacked on the streets.

It’s easy to draw parallels and say “If I was alive back then, I would have done this” but we have to learn from past mistakes to avoid similar occurrences from taking place in the future.

DAY 7: Yesterday, we focussed on the race riot that took place in Liverpool but it’s important to remember similar violent attacks also took place in London, South Shields and Salford. Today we’re going to touch upon the Newport race riots and why we should remember it.

As with Liverpool, the race riot that took place in Newport was a result of postwar job shortages, ongoing strikes with workers and rising unemployment. Resentment and anti-Black hostility resulted in violence inflicted against Black people and other minoritised ethnic groups.

Violent attacks were justified by those who carried them out, claiming Black, Asian and other minoritised groups were taking over and stealing jobs that were previously occupied by predominately White, working class Britons.

One of the more illuminating facts about the Newport Race Riots was the government’s decision to repatriate non-White individuals. Many refused to leave as they had established themselves Wales, whereas others were born and bred there and had no where else to go.

Also, more than half Black people who were arrested by the police during the riots won acquittal. This isn’t to say the courts sought to remedy racist policy. Black people who were persecuted after the riots received harsher sentencing than their white counterparts.

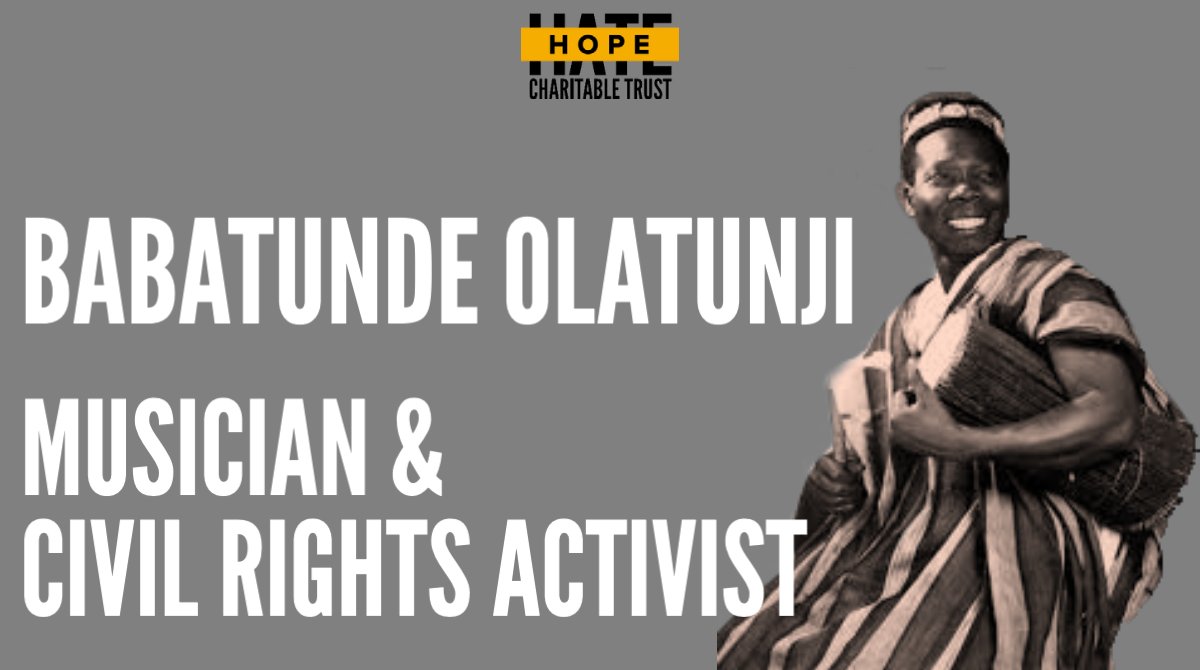

DAY 8: FROM LAGOS TO THE WORLD

We always talk about the Civil Rights movement as if it was solely an American movement but one thing that’s neglected is the role of international actors in campaigning for equal rights. One of these individuals was Babatunde Olatunji.

We always talk about the Civil Rights movement as if it was solely an American movement but one thing that’s neglected is the role of international actors in campaigning for equal rights. One of these individuals was Babatunde Olatunji.

Babatunde, a pioneering Nigerian drummer who came to United States in the 1950s, encountered ignorant comments about his culture alongside harmful stereotypes about Africa whilst studying at Morehouse college.

He sought to debunk these untruths by speaking openly about his culture, talking about the continent’s rich traditions and beliefs. Music became the medium for doing this, where he introduced traditional Yoruba drumming to American audiences.

He galvanised students to protest against the Jim Crows laws in the South, staging his own protest on public buses. He continued to challenge segregation, and his social activism led him to meet MLK Jr, Malcolm X and other prominent figures in the Civil Rights Movement.

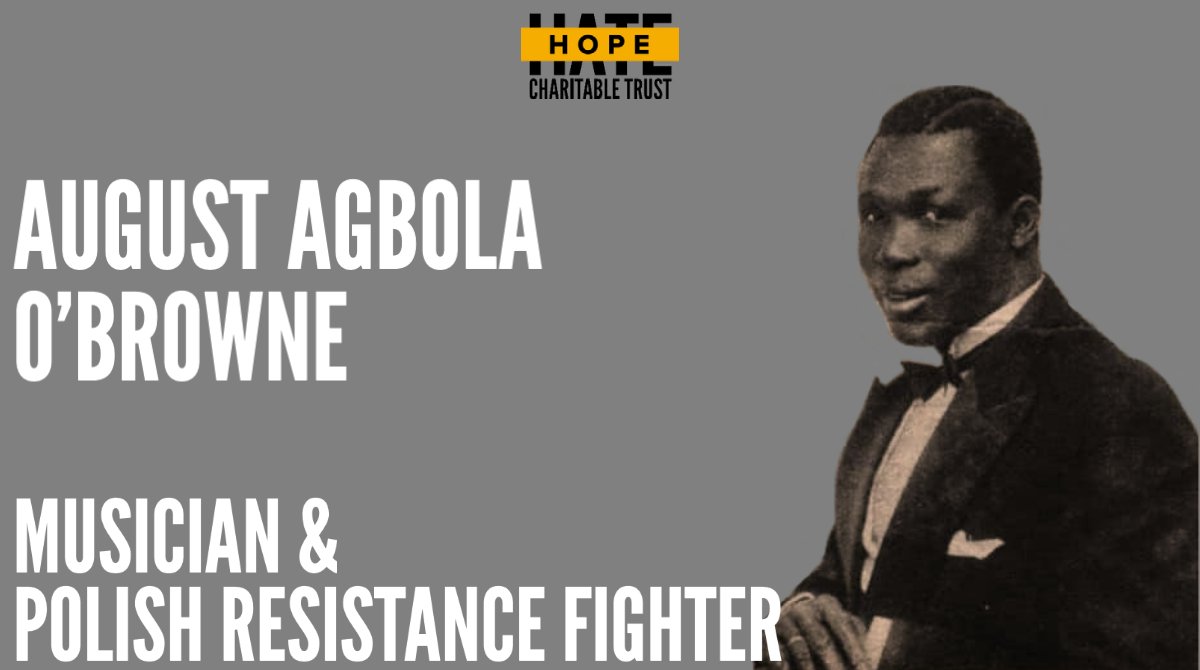

DAY 9: August Browne has gained a lot of attention recently but who was he, and what was his contribution to the polish resistance movement?

August Agbola Browne (or O’browne) was one of the many foreign-born volunteers who joined the Polish resistant movement during the Second World War. He had been living in Poland for 17 years by this point, and had married a Polish woman who bore him two sons.

Browne joined the resistance against Nazi-occupied Poland in 1939 under the code name “Ali”. He distributed underground newspapers & sheltered refugees from the ghetto before joining the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Here he fought in the Śródmieście Południowe district.

Browne also served in the communication centre as a phone operator until the Nazi’s brutally crushed the uprising, killing 200k people in total. Roughly 85% of the city was destroyed & an estimated 16k fighters were killed in the 63-day struggle. O’Browne survived the decimation

O’Browne continued to live in Poland before relocating to London where he died in 1976.

You can read more about his life here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-54337607">https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/worl...

You can read more about his life here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-54337607">https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/worl...

DAY 10: Let’s talk about Doris Morris. Information about Doris Morris and her work in local communities are hard to come by. However, she was known for campaigning to protect workers’ rights.

Born in Jamaica in 1921, Morris moved to Britain in 1956 and worked as a seamstress and then as a childminder. She joined the Decca Radar company in Battersea in 1971, before becoming a shop steward for the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Union.

Morris was a skilled orator and her talent for public speaker helped her rise through the trade union ranks, where she eventually became a convenor.

INTERESTING FACT: Doris& #39;s daughter was Olive Morris, a community activist who campaigned for racial, gender and squatters’ rights

INTERESTING FACT: Doris& #39;s daughter was Olive Morris, a community activist who campaigned for racial, gender and squatters’ rights

DAY 11: DAY 11: We know of William Wilberforce and his role in the abolitionist movement, but have you heard of Phyllis Wheatley (pictured), Mary Prince or Ottobah Cugoano?

All of the individuals mentioned (alongside many others) were noted for their ability to produce poignant and powerful anti-slavery texts, including petitions, poems and autobiographies.

Phyllis Wheatley published a collection of poems which captured the realities of slavery for the enslaved, before covering themes such as rebellion and revolution.

Cugoano published a book highlighting why slavery is inherently “UnChristian”, effectively attacking the Church’s role in supporting and enslaving Africans.

Mary Prince wrote about the pain she had suffered whilst enslaved as a way to spread anti-slavery messaging. Her work appealed to women mostly, and this lead to the establishment of anti-slavery societies across Britain.

One thing that’s worth mentioning is Wheatley, Prince and Cugoano were once enslaved. They could have used their freedom to build a new life but they dedicated their time to ending a condition that brutalised and dehumanised individuals for the sake of profit.

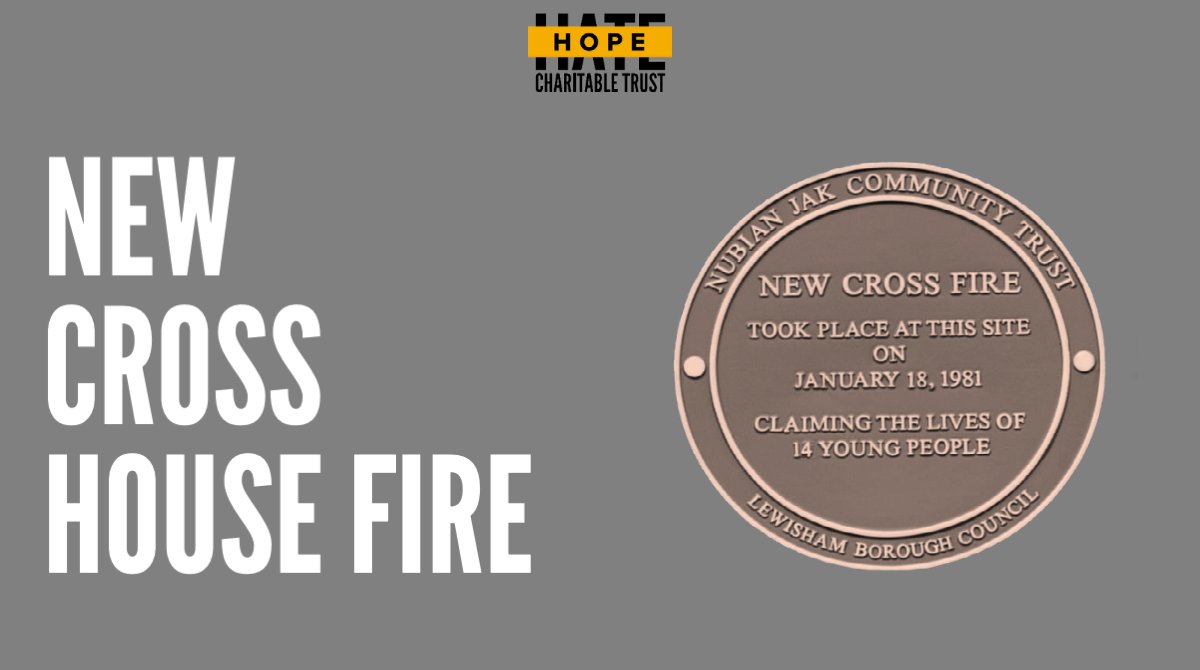

DAY 12: It started off as a birthday celebration to mark Yvonne Ruddock’s 16th birthday at her Deptford home. Many of her friends came over to mark this occasion, enjoying the music, the atmosphere and each other’s company.

Little did they know the night would end in tragedy.

Little did they know the night would end in tragedy.

A fire broke out in the early hours of the morning while many Yvonne’s friends were still in her house. 13 people had died and another 27 people were injured whilst escaping the two-story building.

Yvonne and her brother were one of the victims who had lost their lives.

Yvonne and her brother were one of the victims who had lost their lives.

One of the survivors committed suicide because he couldn’t deal with the the trauma of losing many of his friends in the fire.

The media’s insensitive depiction of the fire, public indifference compounded by alleged police mishandling of the case led to growing frustration...

The media’s insensitive depiction of the fire, public indifference compounded by alleged police mishandling of the case led to growing frustration...

and resentment amongst Lewisham residents and the wider Black community.

More than 10,000 people took part in a protest denouncing alleged police incompetence 6 weeks after the fire. Later that year, a string of riots took place across Britain, including the 1981 Brixton riots.

More than 10,000 people took part in a protest denouncing alleged police incompetence 6 weeks after the fire. Later that year, a string of riots took place across Britain, including the 1981 Brixton riots.

DAY 13: The 1981 Brixton Riots took place at a time where there was a global economic downturn, rising unemployment and crime in inner-city areas. People living in overcrowded places were housed in poor conditions with little support from their local councils.

The Met police sought to address rising crime rate by stopping and searching individuals. A disproportionate number of Black youths were stopped and search and in the five days leading to the riots, 943 stop and searches took place in Brixton alone.

Tension between the police and the Black community were already at a boiling point but it was a misinterpretation of events that led to racial tensions spilling over.

The riots took place over the course of 3 days.

Roughly 7000 police officers were deployed and they used dogs to stop the troubles but the heavy police presence on heightened the tensions.

Rioters threw missiles at the police and attacked commercial businesses.

Roughly 7000 police officers were deployed and they used dogs to stop the troubles but the heavy police presence on heightened the tensions.

Rioters threw missiles at the police and attacked commercial businesses.

282 people were arrested - most of whom where Black - and the British government announced an inquiry into the disturbances (to be covered later on this week).

DAY 14: Brixton wasn’t the only area where riots took place in England, 1981. Many other riots occurred in major cities across the UK where social deprivation, high employment and racial tension amongst the police and the Black community were prevalent.

The Toxteth riots came about after long-standing tensions between the police and the local Black community. Merseyside police were known for aggravating Black youths - particularly young Black men - using the ‘sus’ laws to target them.

Mass rioting took place over a 48-hour period in Moss side, Manchester, as well. Similar events occurred in Bristol, Chapeltown, Handsworth and small pockets in London also.

The riots culminated in the Scarman Report (to be covered tomorrow).

The riots culminated in the Scarman Report (to be covered tomorrow).

DAY 15: The Scarman report (1981) was the official inquiry that looked into the root causes of the Brixton riots. One area of concern was the issue of policing, and how their heavy-handed methods antagonised Black communities across the country.

Youth workers, campaign groups, Lambeth council and police commissioners gave evidence as part of the inquiry.

The report concluded the Met had become too remote from the communities they police, & their methods failed to recognise Britain’s changing cultural landscape.

The report concluded the Met had become too remote from the communities they police, & their methods failed to recognise Britain’s changing cultural landscape.

Also, the report touched upon the structural disadvantages Black people experienced in inner-city areas, in addition to highlighting the police disproportionately targeting Black people when it came to the use of stop and search.

In spite of these findings, the report concluded that “institutional racism” was non-existent and the police were not to blame for the riots.

Though the report was lauded by politicians, community leaders and police commissioners, the recommendations were seldom implemented.

Though the report was lauded by politicians, community leaders and police commissioners, the recommendations were seldom implemented.

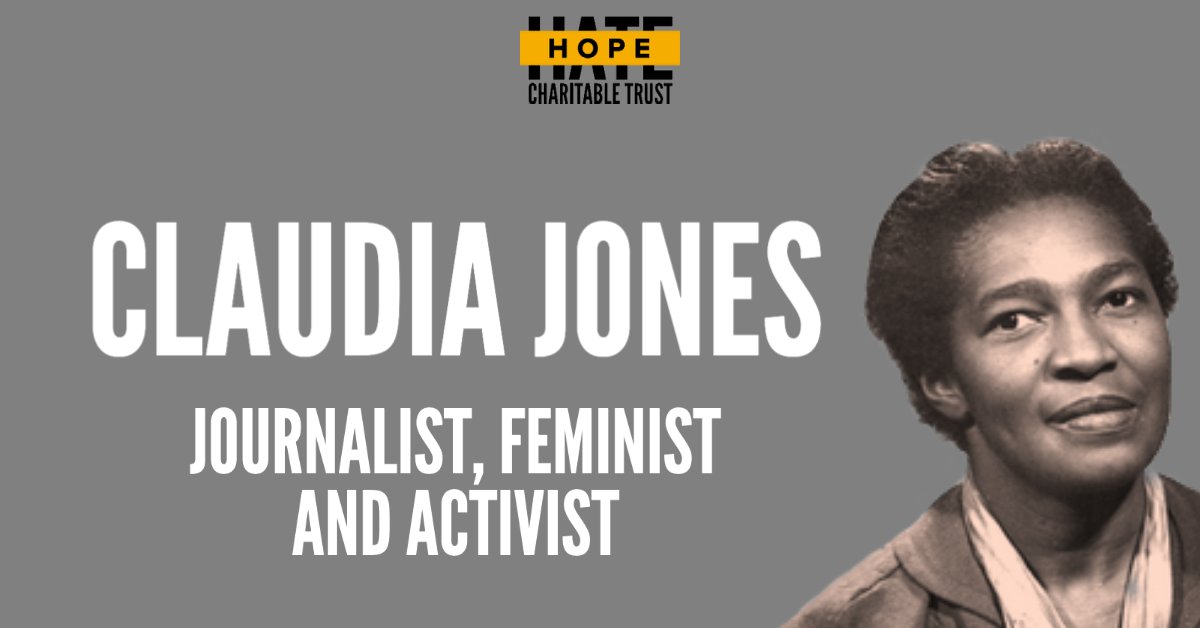

DAY 16: If you saw Google doodle’s feature of Claudia Vera Cumberbatch - better known as Claudia Jones - you would have discovered she was an absolute powerhouse. The Trinidad-born feminist was also a skilled orator, journalist, community activist and much more.

She founded and served as the editor-in-chief for the West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News—Britain’s first, major Black newspaper. Jones used this platform as a vehicle to unify Black people in the fight against discrimination globally.

Jones was deported from the US to the UK after being imprisoned for her political activities. She sought to tackle racial tensions by creating an annual Caribbean carnival, now known as the Notting hill Carnival.

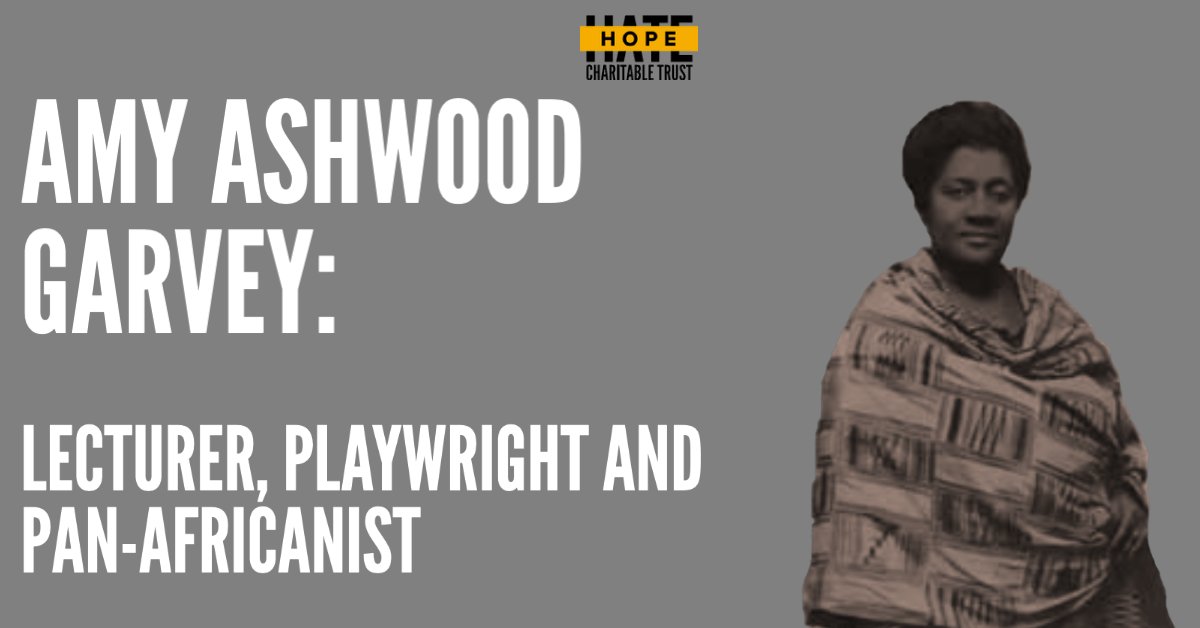

DAY 17: Amy Ashwood was an influential figure in the pan-Africanist movement who campaigned for the rights of African women. Born in Port Antonio, Jamaica, Ashwood was heavily involved in political activism and exchanged ideas with her soon-to-be husband, Marcus Garvey.

She travelled to the USA in 1918 where she became the first secretary and a board member of the newly formed Universal Negro Improvement Association - a pan-African organisation that called for economic self-sufficiency & the creation of an independent Black nation in Africa.

In this role, Ashwood established the UNIA’s newspaper "The Negro World". It detailed the need for self-determination and racial uplift. The Negro World had an extensive international reach, with its readership covering millions of people in Africa, Asia, the Americas & Europe.

After leaving the UNIA, Ashwood continued her work calling for African independence and unifying Black people across the diaspora. She set up a number of groups where Black people could collaborate, in addition to organising the 5th Pan-African Congress in Manchester (1946).

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

https://www.instagram.com/hopenotha..." title="DAY 3: Olive Morris (1952-1979) doesn’t get enough credit for her community activism work, and her role in campaigning for racial, gender and squatters’ rights. You can read about her politics and legacies on our IG pagehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⤵️" title="Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten"> https://www.instagram.com/hopenotha..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://www.instagram.com/hopenotha..." title="DAY 3: Olive Morris (1952-1979) doesn’t get enough credit for her community activism work, and her role in campaigning for racial, gender and squatters’ rights. You can read about her politics and legacies on our IG pagehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⤵️" title="Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Nach rechts zeigender Pfeil mit Krümmung nach unten"> https://www.instagram.com/hopenotha..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>