My new @JECRepublicans report.

The basics: saving often gets a bad rap from demand-side macroeconomists, especially during recessions. However, under the particular circumstances of COVID-19, it& #39;s doing some good stuff!

https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/analysis?ID=754B52C6-04CD-458B-8755-98D1219398F1">https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/in...

The basics: saving often gets a bad rap from demand-side macroeconomists, especially during recessions. However, under the particular circumstances of COVID-19, it& #39;s doing some good stuff!

https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/analysis?ID=754B52C6-04CD-458B-8755-98D1219398F1">https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/in...

Usually demand-side economists say saving is bad in recessions, because, by not spending, you are also not raising the income of others.

Why is COVID-19 different?

1. There are public health reasons to forgo some spending

2. Personal income has risen, mostly for policy reasons.

Why is COVID-19 different?

1. There are public health reasons to forgo some spending

2. Personal income has risen, mostly for policy reasons.

Americans saved a ridiculously huge amount of money in Q2 2020. Absolutely ridiculous. Biggest of all time, hands down, about as much as the next three biggest quarters for saving combined.

The worst case scenario for this saved money, from a demand-side economist& #39;s perspective, is that people hold it in cash or very-low-risk savings accounts. Then it doesn& #39;t do anything to return people to work now.

But even then, it can still be spent later.

But even then, it can still be spent later.

Say that COVID is vanquished sometime in 2021: then there& #39;s money ready to go and purchase Taylor Swift tickets or vacations or whatever else.

That pulls Americans back into the labor market to do the sound setup, take the tickets, run the customer support lines, and so on.

That pulls Americans back into the labor market to do the sound setup, take the tickets, run the customer support lines, and so on.

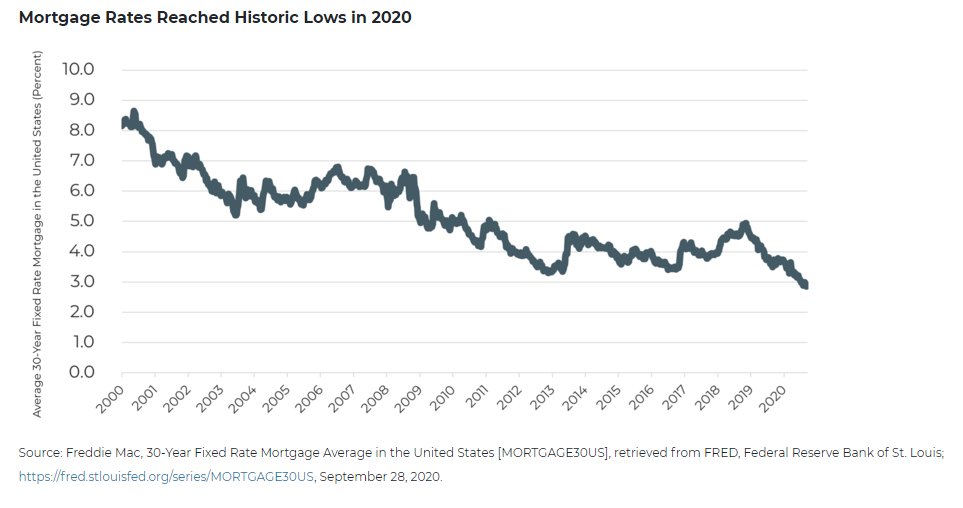

But I think the saved money is also helping us out in the meantime. One way it& #39;s doing that is through mortgages.

Mortgages have been bid up in price to the lender (or down in interest rate charged to the borrower.) This is helping people purchase homes, even in difficult times.

Mortgages have been bid up in price to the lender (or down in interest rate charged to the borrower.) This is helping people purchase homes, even in difficult times.

*I should note I am using "saving" in a sense that includes "invest in a financial product that enables spending by a firm or household." I don& #39;t mean it in the "hoard cash and don& #39;t enable spending, even on capital goods" sense. It& #39;s bad that econ has two definitions for "save."

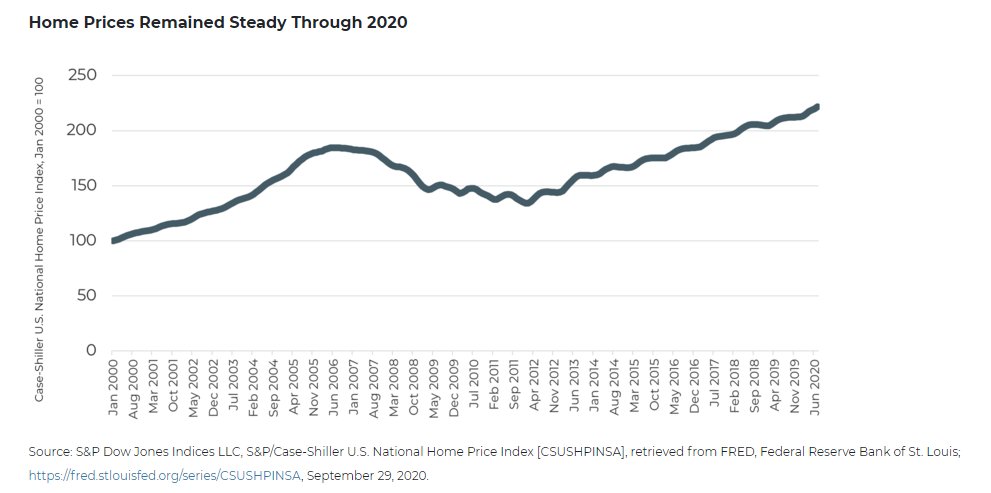

Here& #39;s what mortgage rates have allowed housing to do: prices have remained steady, rather than their frequent custom of dropping in price during recessions.

This is, on net, a good thing.

This is, on net, a good thing.

"But Alan: don& #39;t you like making houses cheaper or more affordable?"

Yes--but only on the supply side. I like making houses cheaper, e.g. by making them more plentiful.

I don& #39;t like making houses cheaper by making people poorer so they can& #39;t afford to spend.

Yes--but only on the supply side. I like making houses cheaper, e.g. by making them more plentiful.

I don& #39;t like making houses cheaper by making people poorer so they can& #39;t afford to spend.

Steady home prices have two benefits:

(1) fewer underwater mortgages (financial stability)

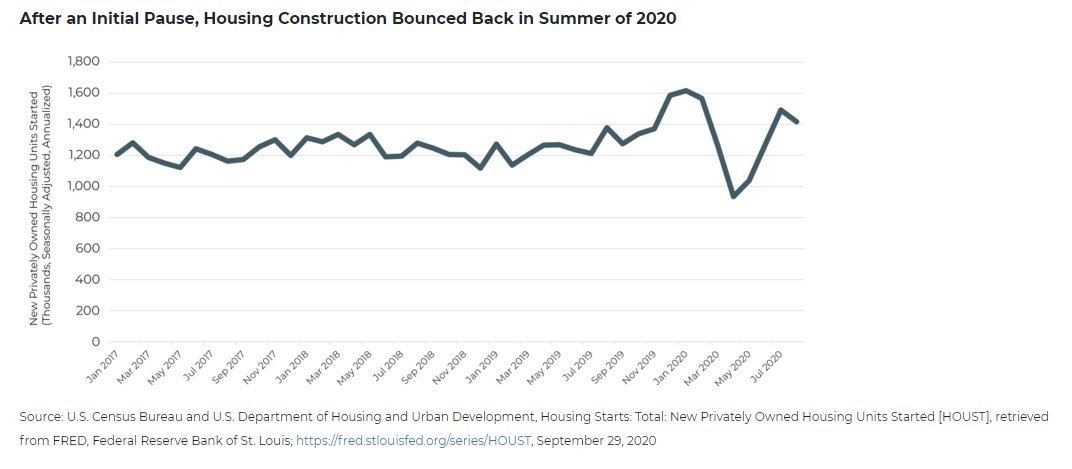

(2) the construction industry can go on paying normal wages and doing its thing

(1) fewer underwater mortgages (financial stability)

(2) the construction industry can go on paying normal wages and doing its thing

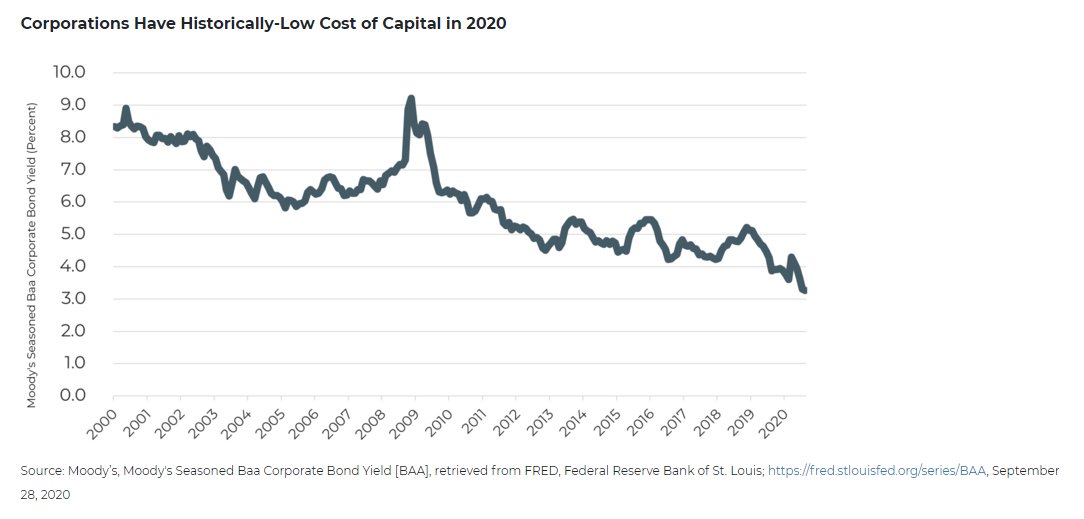

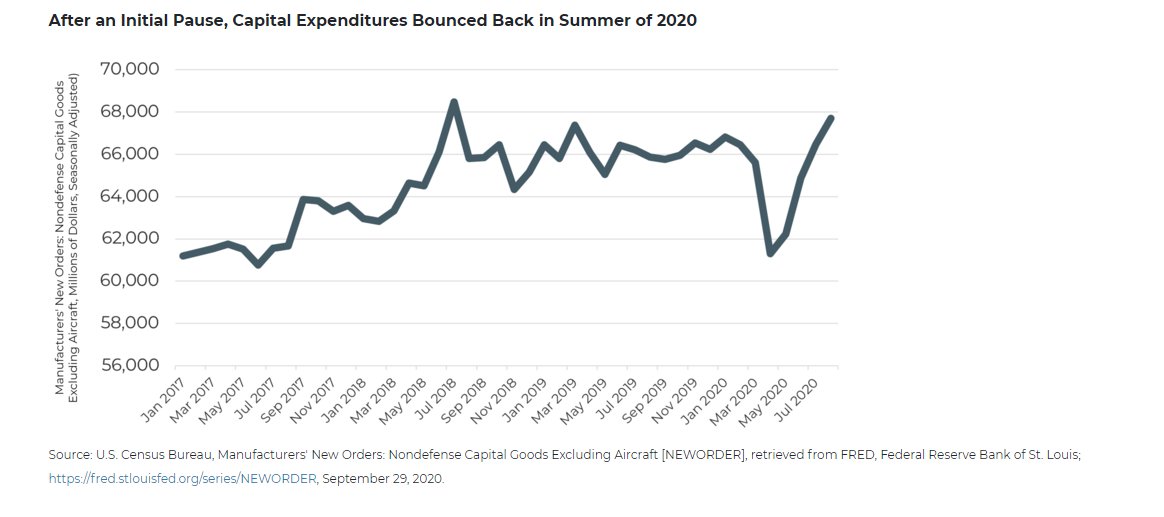

A similar kind of thing is going on with corporate projects. The big supply of saving rushed in and reduced the cost of capital to historic lows.

This is one type of bond, a sort of middle-tier-risk bond, but bonds all tend to move in the same direction most of the time.

This is one type of bond, a sort of middle-tier-risk bond, but bonds all tend to move in the same direction most of the time.

Stocks are also at low yields (or, if you invert the definition, high valuations.)

A lot of people have asked me "why is the stock market up if the future obviously got worse since November?" This is kind of the answer, here: expected future yields on assets are down.

A lot of people have asked me "why is the stock market up if the future obviously got worse since November?" This is kind of the answer, here: expected future yields on assets are down.

One could say the stocks and bonds have actually gotten worse (in terms of the future returns), and they are simply being transacted at higher prices.

This isn& #39;t actually a contradiction. You just have a lot of saving--a historical high--looking for stuff to invest in.

This isn& #39;t actually a contradiction. You just have a lot of saving--a historical high--looking for stuff to invest in.

This lower cost of capital signal is conveying a message to firms: "go ahead with your capital investment projects, still, even if they& #39;re not quite as good as before. It& #39;s fine, we& #39;re expecting lower returns, it& #39;s okay."

And so the firms returned to investing:

And so the firms returned to investing:

Yes, this situation is a little bit sad for savers--at least, those who are buying into the market now, with low expected returns in the future.

But better this than the alternative of laying off the people who build capital goods and putting them on unemployment.

But better this than the alternative of laying off the people who build capital goods and putting them on unemployment.

A few other things about "investment" and firms: you can expand your definition of investment a little bit to comprise any "negative cash flow in the short run, positive cash flow in the future" project--even if it doesn& #39;t look like a typical capital good.

One example might be retaining workers, even those who can& #39;t be used super-productively while COVID is still around.

Negative in the short run, but many employee/employer/coworker relationships are valuable and worth preserving in the longer run.

Negative in the short run, but many employee/employer/coworker relationships are valuable and worth preserving in the longer run.

I expect firms have a *lot* of things that are useful in the long run (that is, when COVID is over) but money-sinks for now.

That& #39;s exactly the situation where deep, generous capital markets are most able to help. That& #39;s their specialty.

That& #39;s exactly the situation where deep, generous capital markets are most able to help. That& #39;s their specialty.

Last point: people hate government lending programs--sometimes for legitimate reasons, like fairness or legal legitimacy--and sometimes because they confuse lending for cash grants.

Why not just let robust private markets full of saving do the lending where possible?

Why not just let robust private markets full of saving do the lending where possible?

I conclude this way: a counterpoint to some varieties of demand-side thinking.

The sort where people say "you want money in people& #39;s hands during recession, but not if it& #39;s saved." I take the first part as a given, but amend the second part to "*even if* it& #39;s saved."

The sort where people say "you want money in people& #39;s hands during recession, but not if it& #39;s saved." I take the first part as a given, but amend the second part to "*even if* it& #39;s saved."

This conclusion can take you some places that are interesting:

(1) There probably should be less worry about "bang for your buck" or "shovel ready" or any of that stuff. Money in people& #39;s hands is always a good remedy to low aggregate demand. (Yes this includes tax cuts.)

(1) There probably should be less worry about "bang for your buck" or "shovel ready" or any of that stuff. Money in people& #39;s hands is always a good remedy to low aggregate demand. (Yes this includes tax cuts.)

(2) Investors will always bear some of the burden of hard times, but it would be better for them to bear that burden a bit more on yields and a bit less on asset prices.

You want to take your recession damage in the lowest friction spot.

You want to take your recession damage in the lowest friction spot.

(3) COVID is a unique recession with all sorts of special rules and restrictions that forced us to go down different paths from usual. The huge individual saving rate was basically an accident.

But by playing a special case, we& #39;ve probably learned insights into the general case.

But by playing a special case, we& #39;ve probably learned insights into the general case.

Last thing: could we have inflation worries if the saving supply is too large and it all rushes back in at once?

Yeah--but if that happens the Fed can hike the federal funds rate, which will raise interest rates on a variety of assets and get many people to slow their spend.

Yeah--but if that happens the Fed can hike the federal funds rate, which will raise interest rates on a variety of assets and get many people to slow their spend.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter