People are still tweeting about the NYT& #39;s piece on the SPARC nuclear #fusionenergy release, so as a fusion PhD student I& #39;m going to explain what it is and isn& #39;t...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/climate/nuclear-fusion-reactor.html">https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/2...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/climate/nuclear-fusion-reactor.html">https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/2...

Commonwealth Fusion Systems is a spin-out from MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Centre. A few years ago they described an innovative design for a power plant called ARC, which proposed using recent advances in high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets to shrink the machine.

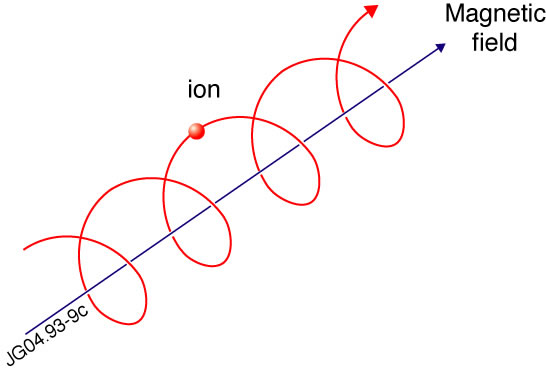

This works because the fusion plasma is held by the strong magnetic field, as each charged particle corkscrews tightly around the field lines.

The higher the field (denoted B), the tighter the corkscrew, effectively shrinking the whole plasma.

The higher the field (denoted B), the tighter the corkscrew, effectively shrinking the whole plasma.

They are not the only group or company pursuing HTS (see @TokamakEnergy ), but they have released the most detailed plan of their goal power plant design. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0920379615302337">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

But this press release isn& #39;t about ARC, it& #39;s about SPARC, their smaller precursor device.

ARC is meant to be a full reactor, with electricity production, tritium breeding, & high uptime.

SPARC is a crank-it-up-and-see experiment meant to demonstrate more power in than out (Q>1)

ARC is meant to be a full reactor, with electricity production, tritium breeding, & high uptime.

SPARC is a crank-it-up-and-see experiment meant to demonstrate more power in than out (Q>1)

SPARC can be roughly compared to ITER, which is also meant to be a net-power demo, with similar gain Q.

The difference is ITER is being built: it can& #39;t now decide to use newer (and riskier) superconducting magnet tech, which was the reason why ITER is physically so much larger.

The difference is ITER is being built: it can& #39;t now decide to use newer (and riskier) superconducting magnet tech, which was the reason why ITER is physically so much larger.

In 1999 (updated in 2007 and since) the (massive, truly international) ITER team released the ITER Physics Basis, laid out in hundreds of pages the details of why they think the particular plasma settings they want to run in ITER should perform how they expect them to.

What the SPARC team have done is released the equivalent set of papers for their design.

This is great, it& #39;s got lots of detail, and shows they are taking the plasma physics challenges appropriately seriously.

This is great, it& #39;s got lots of detail, and shows they are taking the plasma physics challenges appropriately seriously.

But you do have to understand that this step of planning a plasma happens for all designs, and because building a full-size reactor costs ~$billions and merely designing one only costs ~$millions then fusion history is literally with so-called "paper reactors".

Some of these actually got built (JET, ITER), some are hopefully to be built but no guarantees (the UK& #39;s STEP), and many never left the drawing board (ARIES-AT, IGNITOR, FNSF)

But this project clearly has private investors! (mainly @eni I believe, make of that what you will)

But this project clearly has private investors! (mainly @eni I believe, make of that what you will)

So is this "Very likely to work"? Yes and no.

Whilst obviously every paper design is intended to work, the high-magnetic field approach is a good argument. Everything plasma scales around that, so it& #39;s a solid claim to things like good magnetohydrodynamic stability properties.

Whilst obviously every paper design is intended to work, the high-magnetic field approach is a good argument. Everything plasma scales around that, so it& #39;s a solid claim to things like good magnetohydrodynamic stability properties.

Small isn& #39;t always better though - it makes some things harder, esp. handling plasma heat exhaust. SPARC says this will be ~10GWm-2 (unmitigated) which is huge, ~10x larger than on ITER!

But I do like their conservative assumptions in how to handle that. https://news.mit.edu/2018/solving-excess-heat-fusion-power-plants-1009">https://news.mit.edu/2018/solv...

But I do like their conservative assumptions in how to handle that. https://news.mit.edu/2018/solving-excess-heat-fusion-power-plants-1009">https://news.mit.edu/2018/solv...

And what do you mean by "work"? More energy out via neutrons than they pumped in to heat the plasma yes, but only for ~10 seconds. 10s is a long time for a plasma that fluctuates in milliseconds or less, but it& #39;s not the days for a power plant. (Also we got Q=0.67 on JET once)

And as I wrote here, the plasma is only one part of a reactor, you also need to develop e.g. the Tritium Breeding Blanket that generates the fuel the plasma needs. And then turn the neutron power into electricity. And have it not fall apart when running. https://theconversation.com/conservative-nuclear-fusion-by-2040-pledge-is-fantasy-their-record-on-climate-change-is-too-little-too-late-124404">https://theconversation.com/conservat...

Another reason why the fusion community likes this ARC project so much is they actually have innovative ideas for how to handle some of these other challenges too, such as a fully liquid blanket into which the plasma& #39;s vacuum vessel is immersed. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258595490_Liquid_immersion_blanket_design_for_use_in_a_compact_modular_fusion_reactor">https://www.researchgate.net/publicati...

The engineering and materials science challenges that come after you get plasma power out are seriously hard, and hinge around a few key materials (such as the REBCO HTS magnets) being able to handle the stress... and take the heat, & survive the neutron bombardment, all at once!

SPARC/ARC/CFS/MIT& #39;s development timeline is more aggressive than the ones I described in that article, but the conclusion as to the relevance to climate change is still broadly similar.

Even if all goes well, you can& #39;t make an arbitrarily small fusion reactor, because the neutrons are at a fixed energy of 13.6MeV.

If you& #39;re technical this paper makes brilliantly simple arguments about the materials and engineering constraints https://aip.scitation.org/doi/full/10.1063/1.4923266">https://aip.scitation.org/doi/full/...

If you& #39;re technical this paper makes brilliantly simple arguments about the materials and engineering constraints https://aip.scitation.org/doi/full/10.1063/1.4923266">https://aip.scitation.org/doi/full/...

Best case is still something technologically complex, needing nuclear regulation, new supply chains, and some waste disposal.

None of it screams cheap, so at best IMO you end up with something vaguely comparable to advanced fission SMR designs, and on a similar/later timeframe.

None of it screams cheap, so at best IMO you end up with something vaguely comparable to advanced fission SMR designs, and on a similar/later timeframe.

This could be very useful in support of future intermittent renewable-dominated grids, and like new fission tech should definitely be supported. But it& #39;s not going to magically make climate change go away or materialise tomorrow or be too cheap to meter or whatever.

Of course fusion has some distinct advantages over fission designs, but it& #39;s unclear to me how much a govt would pay for those. I actually have a paper coming out about this very soon.

/ https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">

/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter