Who& #39;s ready for another #thread on photographic materiality and digitization?  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤓" title="Nerd-Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Nerd-Gesicht"> Read on

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤓" title="Nerd-Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Nerd-Gesicht"> Read on  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">

The photographs shown above are: German prisoners in a POW camp at Langemarck, 26 September 1917, Ernest Brooks. We see it as a vintage press print (check out that caption) and as a negative owned and digitized by the IWM, © Q 3064.

IWM Research Curator of Photography, @HilaryRoberts57 pointed out the other day that my side-by-side comparison of objects wasn& #39;t accurate, because I hadn& #39;t pointed out that one was a neg and the other a print. She was 100% correct in this.

Let& #39;s go back a little further. In 1839, two separate methods for picture making were announced to the world. The first was the Daguerreotype. It& #39;s a single-positive-process, meaning you get an image and no negative.

(This particularly beautiful object is: [Unidentified woman, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front, wearing white cap and holding daguerreotype case], unattributed, ca. 1840, LOC 2004664500).

A 21st century equivalent to this might be the Polaroid or Fuji instant photograph. [Rachel E. Andrews and Carla-Jean Stokes in Paris], Fuji instant photograph by Lisa Yarnell, May 2014.

Another process was also released in 1839, the Calotype. This process results in a paper negative that can be reproduced into several positive prints. The problem is, the images aren& #39;t altogether sharp.

(Photograph is: [David Octavius Hill, 1802 - 1870. Artist and pioneer photographer], salted paper print from a Calotype negative, Hill & Adamson, ca. 1843-47, National Gallery of Scotland, PGP HA 2054).

Beginning in 1851, Frederick Scott Archer invented a new process that would bring together the sharpness of the Daguerreotype with the reproducibility of the Calotype. It was the wet-collodion glass plate negative.

By the end of the century, the plates were available commercially as gelatin dry plates. This is what most photographers during the South African War, Wars in the Balkans, and First World War used.

So here& #39;s the thing: Why do the objects I showed at the top of this thread look drastically different? One is a negative and one is a print. We should never throw shade at an object for being a negative - this was never the object that wartime audiences were meant to view.

Audiences of the First World War primarily viewed war photos in the press. Here, for example, is one of Ernest Brook& #39;s prisoner portraits in the Illustrated War News. We again get a sense of that beauty and tonality than in the neg.

(Above object was digitized by @BNArchive, and is the June 26, 1917 issue of the Illustrated War News).

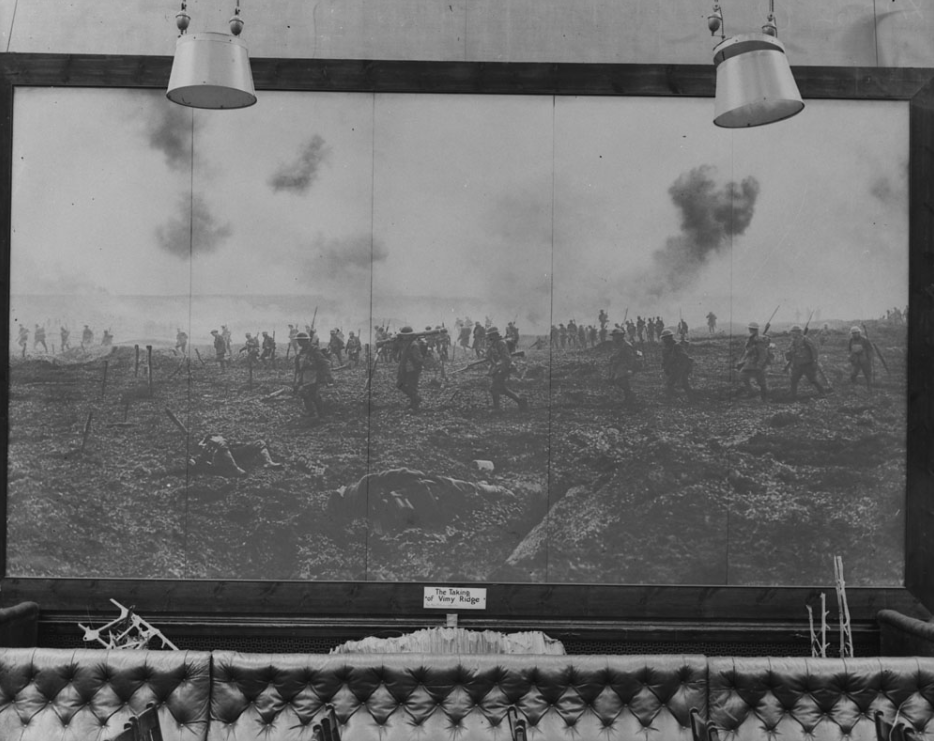

Tens of thousands of spectators also viewed photographs on exhibition. We don& #39;t really have a way of knowing the tones of these massive enlargements, this is another way many people viewed war photos. To learn more, check out work by @teaandnerdery.

(Photograph shows: The Taking of Vimy Ridge on view at Grafton Galleries, London, 1917, unattributed photograph, Library and Archives Canada).

Finally, as a result of these exhibitions (which travelled through the UK, some went to Paris, and others went to Canada and the US) visitors were encouraged to buy prints of the photographs.

Thus, audiences 100+ years ago viewed photographs that look like the print we saw above. Or ones that looked like this:

(The above are 4 prints from my own collection).

Growing up, most of us had photograph albums in our homes. We showed prints, not negs. It was the same during the #FWW - the negs that were produced weren& #39;t really meant to be seen. They were shared all around London to different press agencies and printing companies.

Again, for the purposes of: printing for the press, putting on exhibition, and selling prints. After the war, those negatives were retained by museums like the IWM and archives like LAC.

The negatives were digitized, and that& #39;s what we see online today. Sometimes they& #39;re absolutely beautiful, and other times they& #39;re less exciting than a print. But that& #39;s not the point: these organizations are preserving an original object and digitizing its image faithfully.

(Most museums all follow the same digi rules. We never alter an object. The digitized surrogate is meant to be a replica of the original. Preservation, baby!)

So what really is the point of this? Well, if you look at this image and think "dang, that sure is flat and lifeless without colour!"

It means you unfortunately haven& #39;t had the opportunity to see this, which is full colour, gorgeous, and not even remotely flat, IMO.

So, in the end, it was all to air my frustration with some of the reasoning behind colourizing photographs. But at least we got to talk about some nerdy things while we were at it.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">" title="Who& #39;s ready for another #thread on photographic materiality and digitization? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤓" title="Nerd-Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Nerd-Gesicht"> Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">">

Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">" title="Who& #39;s ready for another #thread on photographic materiality and digitization? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤓" title="Nerd-Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Nerd-Gesicht"> Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">">

Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">" title="Who& #39;s ready for another #thread on photographic materiality and digitization? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤓" title="Nerd-Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Nerd-Gesicht"> Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">">

Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">" title="Who& #39;s ready for another #thread on photographic materiality and digitization? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤓" title="Nerd-Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Nerd-Gesicht"> Read on https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇🏻" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten (heller Hautton)">">

![A 21st century equivalent to this might be the Polaroid or Fuji instant photograph. [Rachel E. Andrews and Carla-Jean Stokes in Paris], Fuji instant photograph by Lisa Yarnell, May 2014. A 21st century equivalent to this might be the Polaroid or Fuji instant photograph. [Rachel E. Andrews and Carla-Jean Stokes in Paris], Fuji instant photograph by Lisa Yarnell, May 2014.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ei2jubgUwAARCmZ.jpg)