Earlier today I came across this just-filed copyright case involving emoji. I& #39;ve skimed the case, and so far it meets my first impression - there& #39;s not much here. At all.

But let& #39;s dig in. The case is Cub Club Investment v Apple; the complaint is here:

https://www.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txwd.1108394/gov.uscourts.txwd.1108394.1.0.pdf">https://www.courtlistener.com/recap/gov... https://twitter.com/questauthority/status/1308047921368178691">https://twitter.com/questauth...

But let& #39;s dig in. The case is Cub Club Investment v Apple; the complaint is here:

https://www.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txwd.1108394/gov.uscourts.txwd.1108394.1.0.pdf">https://www.courtlistener.com/recap/gov... https://twitter.com/questauthority/status/1308047921368178691">https://twitter.com/questauth...

For those who want extra background on emojis and the law, @ericgoldman wrote an excellent paper on the topic in 2018, which is linked below. I didn& #39;t take time to review it today, but IIRC it covers some of the same ground I& #39;m going to tonight.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3133412#">https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/pape...

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3133412#">https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/pape...

Let& #39;s dig into the complaint, and see what& #39;s what.

The case states - or at least *attempts* to state - several causes of action. I& #39;ll cover copyright in depth, and highlight the major issue with the trade dress claim.

The case states - or at least *attempts* to state - several causes of action. I& #39;ll cover copyright in depth, and highlight the major issue with the trade dress claim.

I& #39;m not going to dig into the state law issues at all aside from saying this:

there may be a few issues with copyright law preempting the state law claims. In fact, I suspect there are.

there may be a few issues with copyright law preempting the state law claims. In fact, I suspect there are.

I& #39;ll skip over jurisdiction and venue. Given the massive issues with the infringement claims, I didn& #39;t see the need do more than skim them.

OK. So the allegation is that the suing company& #39;s founder& #39;s daughter had the idea for racially diverse emoji, and that they got them on the App Store in 2013.

They also allege that they have registered copyrights in emoji covering 5 skin tones. And that (paging @design_law) there are pending utility and design patent applications for the "diverse emoji."

(There& #39;s no claim based on the pending applications.)

(There& #39;s no claim based on the pending applications.)

(Credit where due, in making sure to allege that the works were registered, CCI has done at least one thing right.)

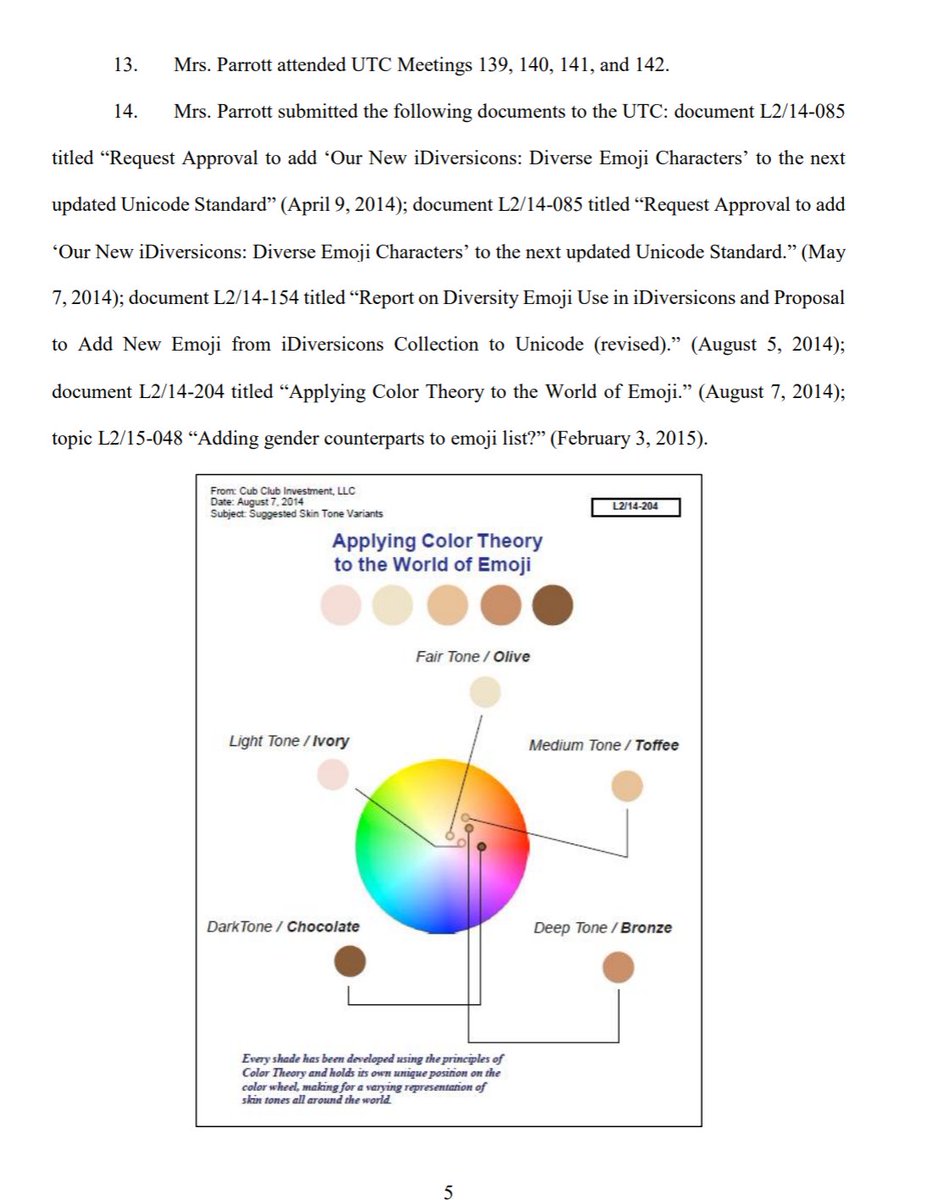

They go on to discuss extensive work that the founder did with Unicode in order to get diverse characters added to the Unicode standard.

That was legitimately good work. When people pick human-looking emoji, they should have options.

That was legitimately good work. When people pick human-looking emoji, they should have options.

Now we get to allegations of discussions between CCI and Apple. The first thing that strikes me here is the degree of overlap with the Unicode meetings. The second is that there doesn& #39;t seem to be anything close to an agreement alleged.

And the third thing that strikes me is that Apple apparently openly stated, as early as 2014, that they were proceeding with development of their own 5-tone emoji.

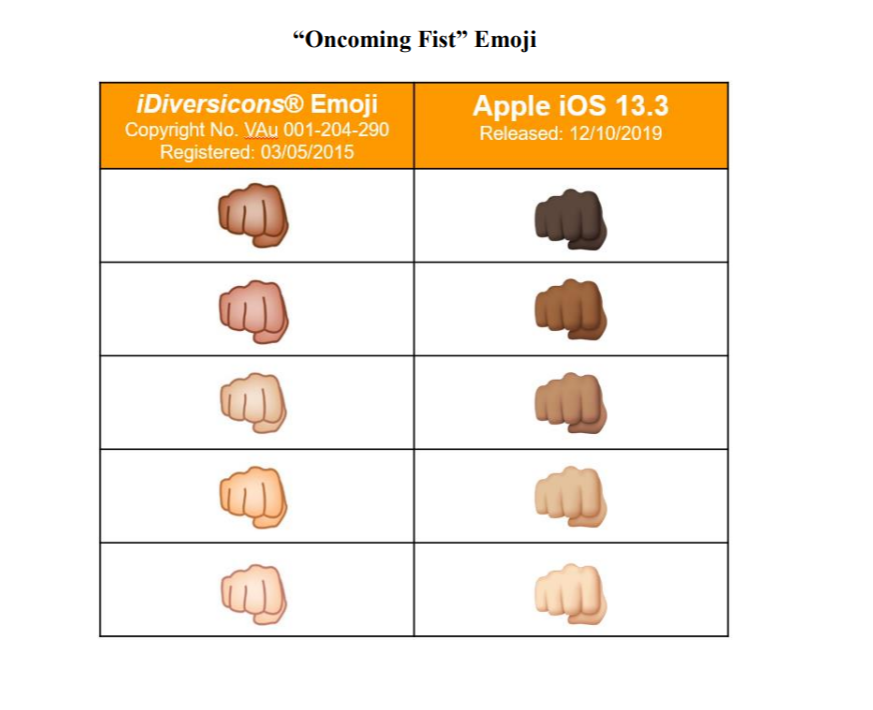

Moving on, we get to the first allegation of copyright infringement - involving the "oncoming fist" emoji.

The pictured Apple iOS 13.3 emoji do not infringe the iDiversicons Emoji.

Let& #39;s talk about why.

The pictured Apple iOS 13.3 emoji do not infringe the iDiversicons Emoji.

Let& #39;s talk about why.

To do that, let& #39;s start by rolling back the clock 130 years, and looking at an 1890 case from England.

The case is Kenrick v Lawrence, [1890] 25 QBD 99. And, despite the fact that emoji - and cell phones, and computers - had yet to be invented, it& #39;s amazingly on point.

The case is Kenrick v Lawrence, [1890] 25 QBD 99. And, despite the fact that emoji - and cell phones, and computers - had yet to be invented, it& #39;s amazingly on point.

Kenrick v Lawrence involved a drawing of a hand marking a box. The drawing was intended to provide guidance for the illiterate on how to mark a ballot. Another company released a similar form and drawing, and Kenrick sued.

And lost.

And lost.

The court had "no doubt that he took the suggestion from the plaintiffs& #39; card." Nevertheless, the court did not find that the drawing infringed.

This was not, however, because there was no copyright in the drawing itself.

This was not, however, because there was no copyright in the drawing itself.

Instead, the court held that "in such a case it must

surely be nothing short of an exact literal reproduction of the drawing registered that can constitute the infringement, for there seems to me to be in such a case nothing else that is not the common property of all the world."

surely be nothing short of an exact literal reproduction of the drawing registered that can constitute the infringement, for there seems to me to be in such a case nothing else that is not the common property of all the world."

This concept is sometimes referred to today as "thin copyright." It exists when a work meets the requirements for copyright protection - as the plaintiff& #39;s diverse emoji most likely do - but where broad protection would in effect prevent others from expressing the same idea.

This is part of a messy area of copyright referred to as the idea/expression dichotomy. Copyright protects expressions, but ideas are free for the taking. It& #39;s similar to the "merger doctrine," but not quite identical - there, there& #39;s no protection at all.

We could get hypergeeky on the distinctions, but they really don& #39;t matter here. The emoji aren& #39;t identical, so either way the plaintiff loses.

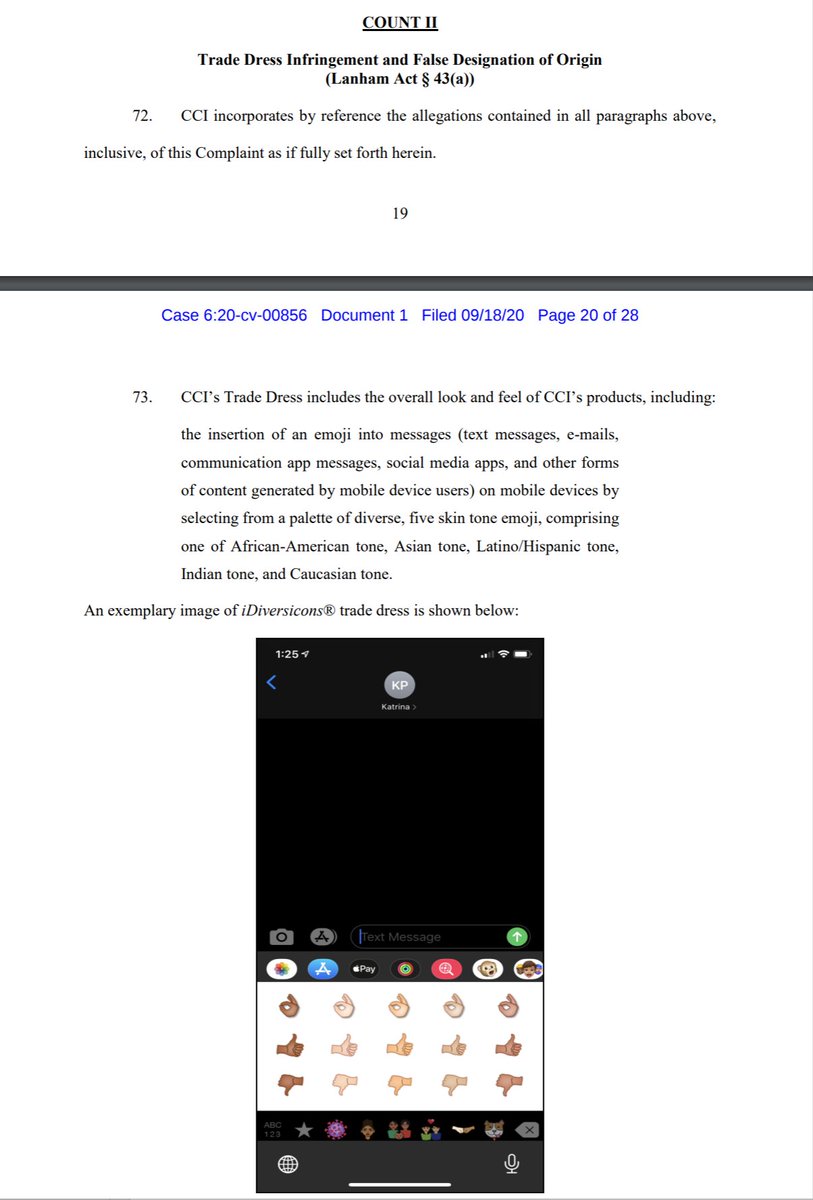

The next several pages show more emoji. And, in each case, there are differences between Apple& #39;s emoji and plaintiffs& #39;. The tones are different; the drawings are different.

Yes, there are similarities, but that& #39;s because there are only so many ways to depict this concept.

Yes, there are similarities, but that& #39;s because there are only so many ways to depict this concept.

As far as I can tell, Apple took, at most, plaintiff& #39;s idea to use five skintones, rather than four, seven, nine, or some other number. But that& #39;s an idea - and it& #39;s probably one that& #39;s baked into the technical unicode standard.

I& #39;m sure that plaintiff would make a great deal more money if everyone licensed her emoji set instead of using their own. (And, IIRC as Prof. Goldman& #39;s paper noted, the lack of standardization is an issue; you can& #39;t be sure the emoji you send is the one that will be received.)

But the thing is, copyright provides no grounds for the plaintiff to claim a monopoly over the use of five skin tones for emoji. Particularly when it& #39;s not the same five shades being used.

The copyright case is DOA.

The copyright case is DOA.

To the extent that the plaintiff& #39;s registration are valid at all, they simply are not infringed.

I know I talked about trade dress a couple of weeks ago, in the context of a faux Funko. The trade dress being claimed here is similar - it& #39;s product design trade dress. But there& #39;s a problem bringing a trade dress claim here.

In Wal-Mart v Samara, 529 US 205 (2000), the Supreme Court held that product design trade dress can never be inherently distinctive, and that protection requires showing what& #39;s called "secondary meaning."

To show secondary meaning, you must show that the product design "identif[ies] the source of the product rather than the product itself."

The head shape and proportions of a Funko, at least arguably, do that. They& #39;re what makes a figure a Funko, not a different kind of figurine.

The head shape and proportions of a Funko, at least arguably, do that. They& #39;re what makes a figure a Funko, not a different kind of figurine.

Here? That& #39;s harder. I think the plaintiff will be hard-pressed to find people who identify "multi-shade emoji" with their company. And I have no idea how they can have product design trade dress in five not-rigidly-specified colors.

I& #39;m pretty sure that claim is dead, too.

I& #39;m pretty sure that claim is dead, too.

The common law unfair competition claim seems to just rehash the trade dress argument in slightly different form.

Same for the misappropriation claim.

Same for the misappropriation claim.

As does, it appears, the unjust enrichment claim.

In all 3 cases, I suspect that a hurdle plaintiffs face is that Apple is accused of doing something they had the legal right to do - develop their own emoji to fit the new Unicode standard.

In all 3 cases, I suspect that a hurdle plaintiffs face is that Apple is accused of doing something they had the legal right to do - develop their own emoji to fit the new Unicode standard.

Now, throughout this thread, I& #39;ve assumed that the plaintiff came up with the idea for a five-tone palette of colors for emoji. It looks, taking the complaint at face value, like the plaintiff put in an enormous amount of effort into getting Unicode onboard with that idea.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter