The above words were uttered in 1960 by Ahmed Farah, a member of the LegCo in Kenya, representing the Somali community.

Farah went on to claim that Somalis and other Muslims from Kenya’s north would “defect” to Somalia while the non-Muslim northerners would immigrate to Ethiopia.

For decades, the northern parts of Kenya, and the North Eastern parts in particular, have been considered by many to be pariah territories within greater Kenya. It started decades ago, in the years after the first world war.

Let’s travel back to that time, shall we?

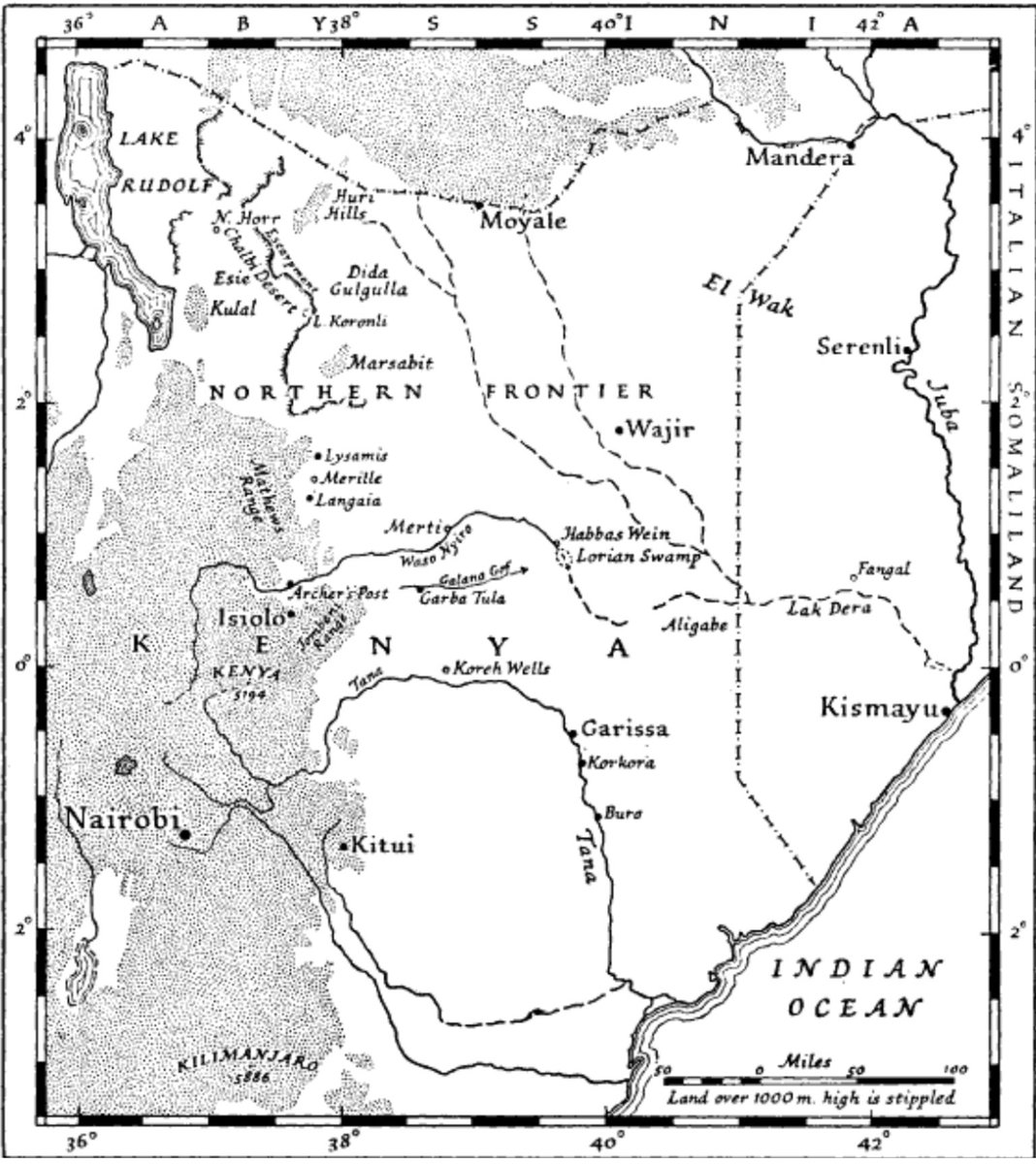

In 1926, through the Outlying Districts Ordinance, the colonial administration proclaimed northern Kenya as a “closed district”. The NFD became something akin to a police state.

Commissioners and other administrative officers were given strong powers. For example, both Europeans and Africans needing to travel to that part of the country required special passes. Also, residents from the north required special approvals to travel elsewhere within Kenya.

Moreover, the administration discouraged urbanization in the NFD. Scarce water supplies, the administration argued, could not sustain rapid urbanisation. The Government also felt the need to “protect the nomads from undesirable elements from the highlands and other places”.

Author A.W. Hodson in his 1927 book, Seven Years In Southern Abyssinia, claimed unnamed government officials had told him that urbanized Somalis “tended to be negative”.

In 1934, eight years after the passing of the Outlying Districts ordinance, another edict – the Special Districts Ordinance – was issued. Further restrictions were imposed on movement of persons entering or leaving the NFD.

Fearing that some zones were overstocked, the government used the Ordinance to apply stringent controls on use of both pasture and water. Indeed, some grazing areas were closed off to the predominantly nomadic communities.

Incensed by these moves, the Somali and Borana decided to starve the colonial administration of taxes.

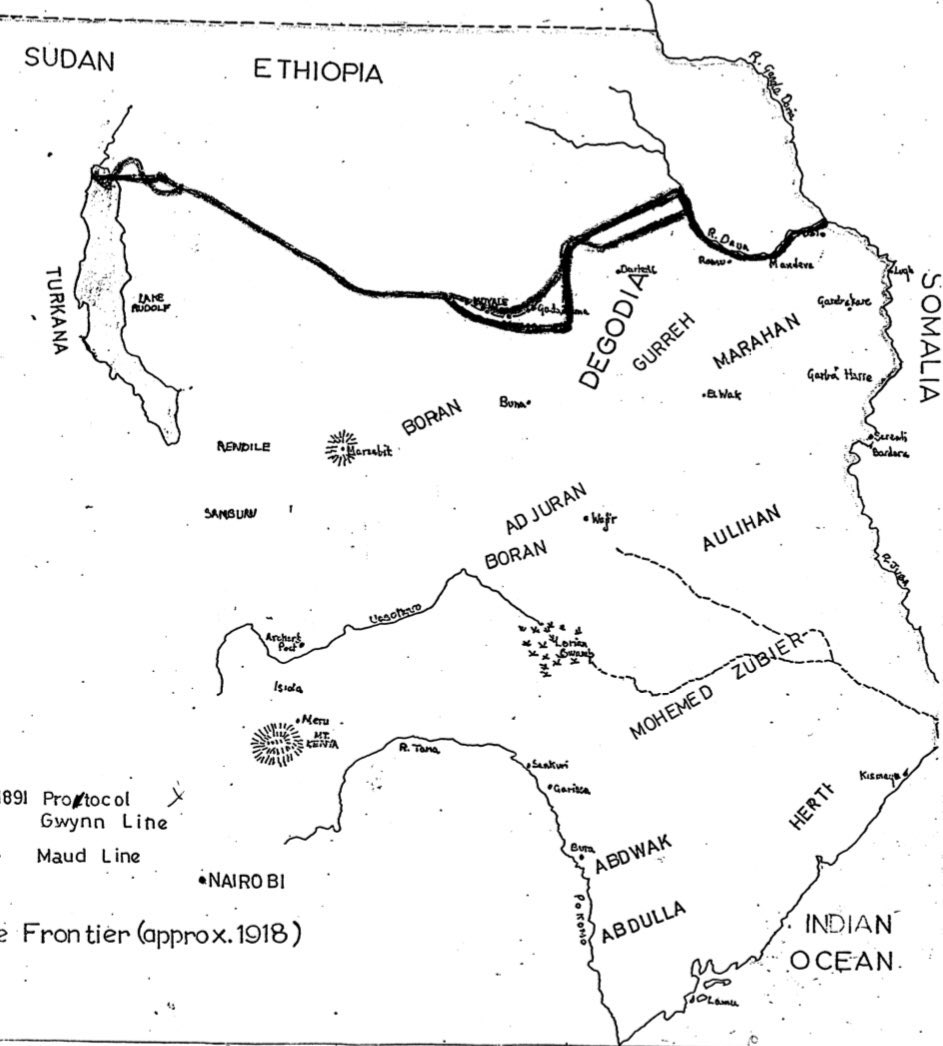

Some clans, the Degodia and Gurreh in particular, crossed over to Ethiopia, where taxation was unheard of. Even in 1923, when there were attempts to fingerprint Africans in the NFD, hundreds of Gurreh clan members escaped to Somalia and Ethiopia.

Since the 1900s, Somalis demanded to be granted special status. Writing in a 1964 edition of the Journal of African Studies, author A. Castagno noted that Somalis refused to be referred to as “natives” or “Africans”. They demanded that the Crown government designate them Asians.

However, the colonial government brushed off these demands but made amends by making certain changes in various ordinances, such as the Somali Exemption Ordinance of 1909. Interestingly, with reference to Somalis, “tribesmen” was substituted for the term “native”.

This meant that although Somalis were Africans, they were not considered “Kenyan Africans”.

Meanwhile, the colonial government repeatedly denied Somalis the opportunity for representation.

Meanwhile, the colonial government repeatedly denied Somalis the opportunity for representation.

Even when Ishaak Somalis in 1938 endorsed one of their own to be a member of the legislative council (LegCo), the colonial regime would hear none of that. In 1958, the NFD finally got someone to represent the region in the LegCo.

He was among several non-Europeans like Musa Amalemba, Wanyutu Waweru, Gibson Ngome and Esmail Nathoo who got elected. However, Somalis rejected their representative, Mohamed Ali Said el-Mandry, on account that he was “not one of us”.

Not long after, the colonial government caved in to pressure from, among other bodies, the Ishaakiya Association and the United Somali Association (which later became the Somali National Union) and allowed Kenyan Somalis to elect a representative.

Ahmed Farah was consequently elected.

But no sooner had Kenyan Somalis found representation than the agitation by a section of them to secede to Somalia started. A Somali group in Nairobi, the National Political Movement, was among political outfits that called on NFD to unite with Somalia.

Interestingly, pro-secessionists landed a key ally – the newly independent republic of Somalia.

Indeed, the Somali president made controversial remarks in 1961 that were viewed by many as inciting Somalis in Kenya. He said something to the effect that self-determination and balkanization did not mean the same thing.

But Somalis were not the only residents of NFD who favoured secession to Somalia. Other communities, such as the Borana, Rendille and Turkana were fervently against the campaign for secession.

Amidst all the secession talk, a clever, pacifist idea was hatched.

The British Government in 1961 formed the Regional Boundaries Commission and a Constituencies Delimitation Commission.

The Commissions toured various parts of the country (sounds familiar?) seeking views from citizens on representation, as well as identifying communities that were inadequately represented.

In 1962, the report of the Regional Boundaries Commission was published.

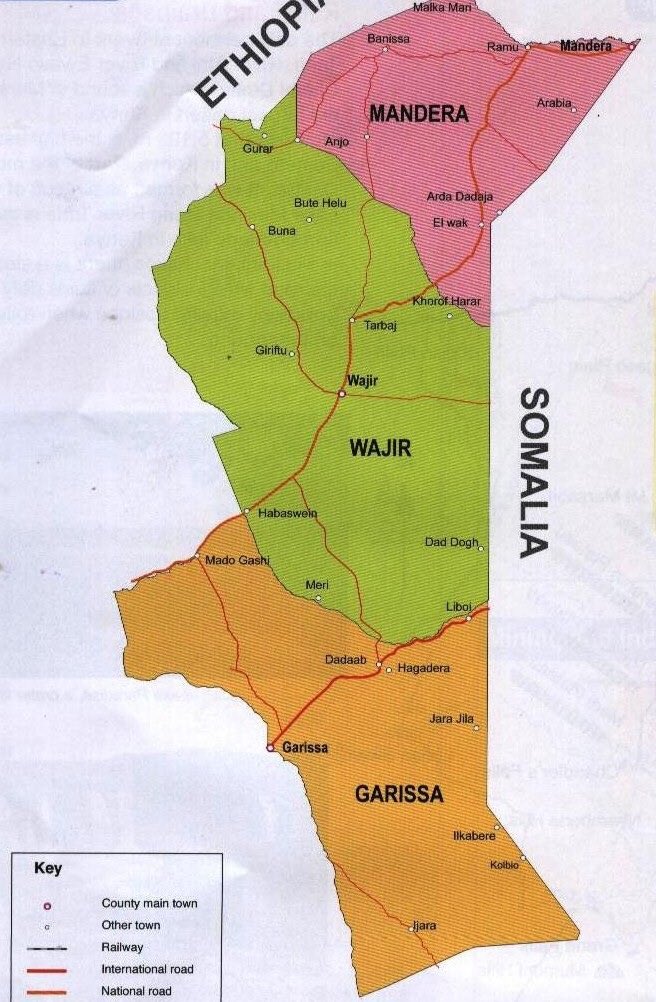

It recommended that the Somalis of Garissa, Mandera, and Wajir be organised in a newly created seventh region, the North-Eastern Region, and that the Somalis of Isiolo and the Muslim Boran of Isiolo and Moyale be placed in another, the Eastern Region.

One entity that did not seem happy with the formation of these two regions was none other than the government of Somalia.

Indeed, the release of the Commission’s report led to protests from Mogadishu and Somali groups, who complained that London had reneged on a promise that there would be no change in the administrative status of the N.F.D. before (Kenya’s) independence.

So seriously was the Somalia government involved with NFD matters that to protest the overall attitude of Britain towards Somalis in Kenya, it broke off diplomatic relations with London on March 18, 1963.

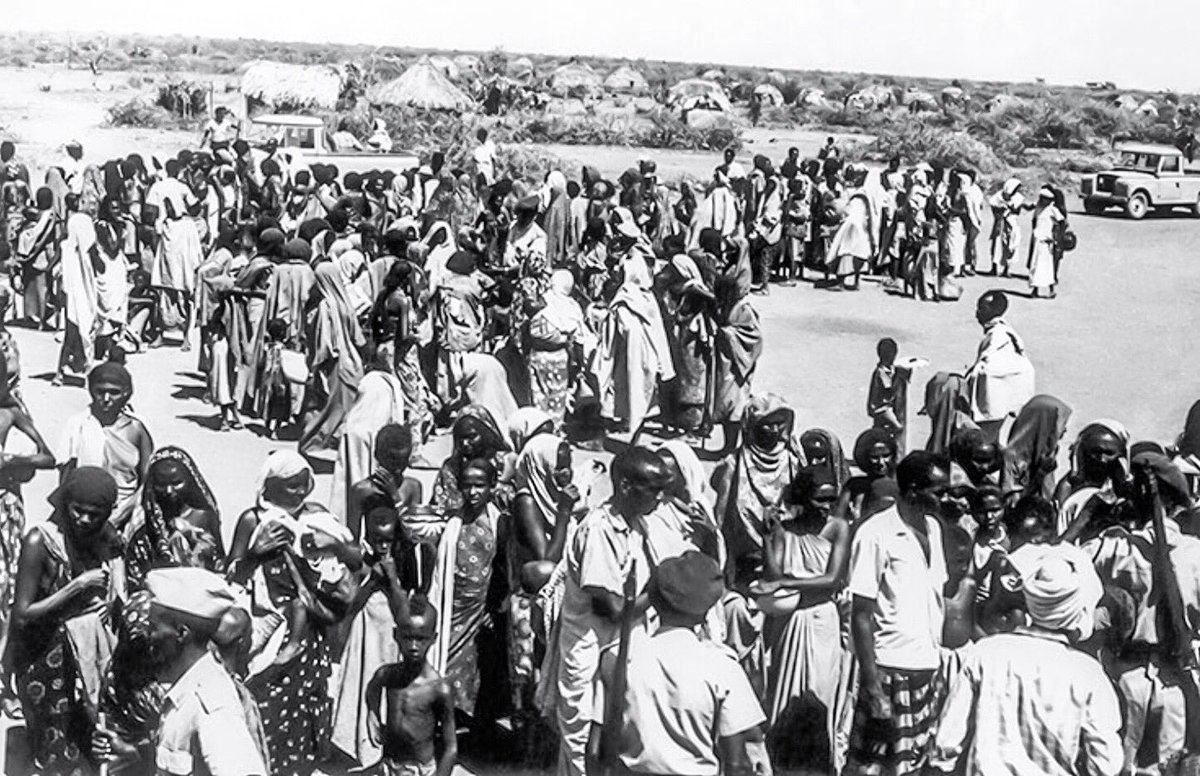

By that time, NFD was already a war zone. Somalia militias targeted government installations in guerilla attacks. Clashes occurred between British officials and Somalis in the north.

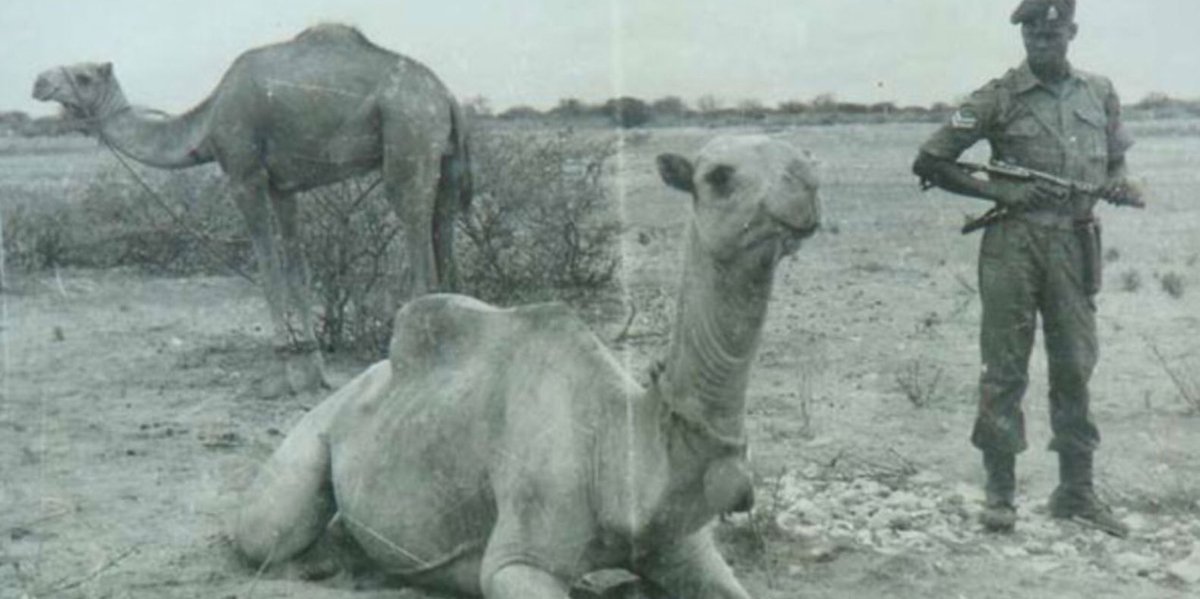

Prime Minister-in-waiting Mzee Kenyatta issued a tough statement calling on Somalis in Kenya who had no interest in keeping the peace to “pack up their camels and leave…”

The insurgency, which came to be known as the Shifta War (after Somali word for bandit), continued well beyond Kenya’s independence.

By the time a ceasefire between the Kenyan and Somalian governments ended the war in 1967, the death toll from the war had well passed the 5,000 mark (Image credit: Nation Africa).

Five decades later, Devolution may have empowered the people of northern Kenya to a significant extent. But sporadic attacks from a different kind of armed Shifta still dog parts of the former NFD.

See also https://twitter.com/historyke/status/914504100305190912">https://twitter.com/historyke...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter