[Thread] Postwar German prosecution of Nazis

I was inspired by @nath4nglx to do this explainer on the ins and outs (and ups and downs) of postwar Nazi trials. It& #39;s a really interesting look into #History, memory, the #Holocaust, and the law. Enjoy!

I was inspired by @nath4nglx to do this explainer on the ins and outs (and ups and downs) of postwar Nazi trials. It& #39;s a really interesting look into #History, memory, the #Holocaust, and the law. Enjoy!

First off, I am not talking about the Nuremburg International Tribunal or the Subsequent Trials. Those were not German prosecutions but were allied prosecutions which relied on different legal standards and methods.

Instead, I& #39;ll be talking about post-1949 trials in Germany.

Instead, I& #39;ll be talking about post-1949 trials in Germany.

If you want resources on those trials, both @HarvardHarvard and @Yale have great websites on them.

http://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/ ">https://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/">...

http://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/ ">https://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/">...

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/imt.asp">https://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_m...

So, in 1949, Germany (West Germany) regained its sovereignty/became a state. I& #39;m not going to deal with the DDR. For our purposes, one of the important elements of the founding of Federal Republic was that became responsible for prosecution of criminals from the Third Reich.

This meant that German police and German district attorneys would investigate and try war criminals. Theoretically, this would be possible due to the continuing efforts of "denazification" begun by the Allies and continued in the Spruchkämmer process.

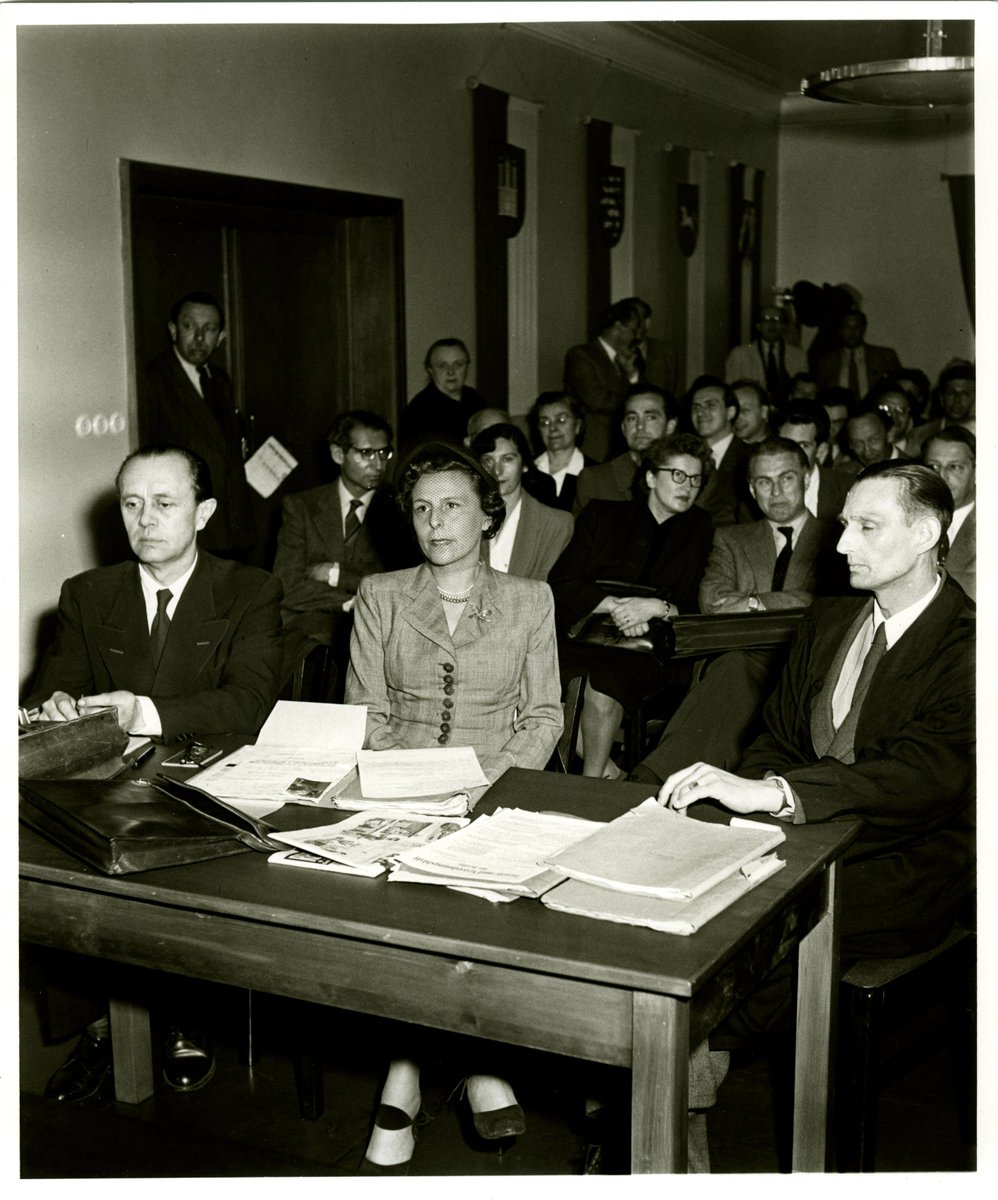

Leni Riefenstahl, 1952 https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">

Leni Riefenstahl, 1952

The goal of the denazification courts was to identify and categorize former Nazis and determine their new place in society. They were ranked by levels of guilt/depth of involvement in the Third Reich. This determined eligibility for pensions and for service in the FRG.

These were not prosecutorial events and were deeply problematic. Many war criminals hid their pasts or never came before a denazification hearing.

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1002826">https://collections.ushmm.org/search/ca...

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1002826">https://collections.ushmm.org/search/ca...

In fact, a good number of SS and police killers (as well as doctors, lawyers, and judges) simply returned to those same positions in West Germany.

In 1949, 81% of Bavarian judges were former Nazis.

Another example:

In 1949, 81% of Bavarian judges were former Nazis.

Another example:

Thus, in many ways, the system was stacked against conscientious prosecutors as in the best of times, former Nazis were reticent to shine too harsh a light on even terrible war criminals for fear of their own past being revealed.

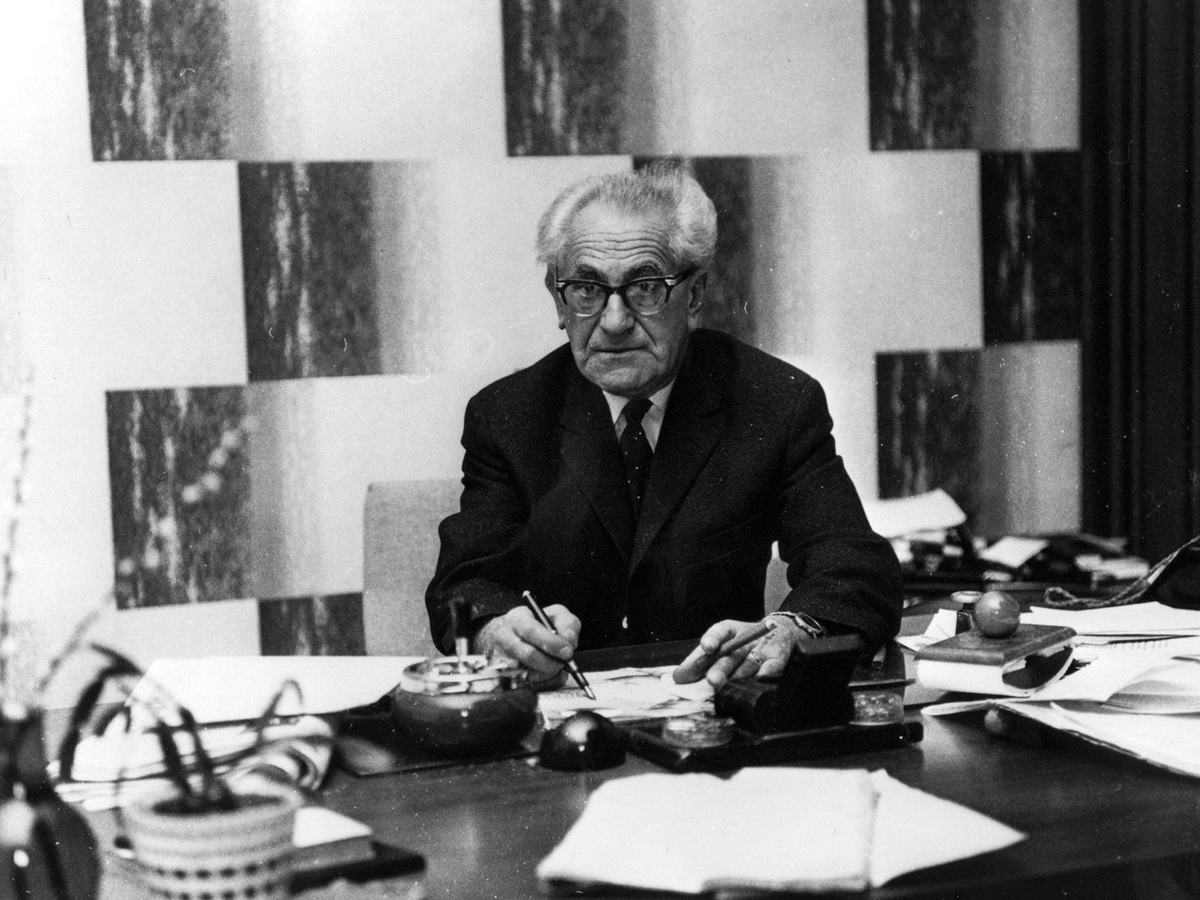

This is not to say that there weren& #39;t a good number of prosecutors genuinely committed to bringing Nazis to justice. One of these was Fritz Bauer, a German-Jewish attorney who returned to Germany in 1949.

There are a couple good films about him.

The People vs. Fritz Bauer (2015) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDTRQWyvzKg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

The People vs. Fritz Bauer (2015) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDTRQWyvzKg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Labyrinth of Lies (2015) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5ovcBGMLEs">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

But, understandably, there was a reticence in Germany to prosecute its own for war crimes, particualrly those that remained undiscovered by the allies.

Authorities wre also hampered by the laws themselves. Germany rejected the crime of genocide and crimes against humanity.

Authorities wre also hampered by the laws themselves. Germany rejected the crime of genocide and crimes against humanity.

These were ex-post-facto laws: they delineated categories of offenses that were not defined by the law at the time. This did not mean that the actions of many war criminals were not illegal under existing law.

But many weren& #39;t...technically.

But many weren& #39;t...technically.

One related example is the persecution of LGBT people which was codified in law (Paragraph 175) from the 2nd Reich making homosexuality illegal. It remained in effect until 1994, in fact. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/paragraph-175">https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/e...

One of the major challenges of relying on existing law was its emphasis on individual and discrete crimes. So, while today it may be obvious that serving as a guard in Auschwitz made one legally complicit in genocide, this was not the case earlier.

Prosecutors had to find Nazis guilty of specific crimes; just being a guard at Auschwitz would not be a crime and of itself or sufficient for a conviction.

This was a major obstacle for investigators and DAs.

This was a major obstacle for investigators and DAs.

The law did not recognize the challenges of prosecuting Nazi crimes. It still required witnesses and evidence that were often almost impossible to come by in terms of linking an individual to the death of someone.

This is why you often see a Nazi mass murderer charged with a seemingly tiny number of murders.

But this was an attempt by prosecutors to use the most conservative estimate to get a conviction. Legally, conviction of 10 murders or 10,000 had the same outcome.

But this was an attempt by prosecutors to use the most conservative estimate to get a conviction. Legally, conviction of 10 murders or 10,000 had the same outcome.

The evidentiary standards often just didn& #39;t fit. We know that eyewitness testimony is shaky in the best of courtroom circumstances. Holocaust survivors routinely got destroyed on the stand and frequently weren& #39;t even called for this reason.

They were asked questions that would routine in a normal trial.

"How do you know it was Person X?"

"What was the name of the victim?"

"What date and time did this happen?"

"How do you know they were dead?"

Naturally, these were often VERY difficult to answer.

"How do you know it was Person X?"

"What was the name of the victim?"

"What date and time did this happen?"

"How do you know they were dead?"

Naturally, these were often VERY difficult to answer.

We should also remember that a college student who has taken a couple courses on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust might well have known more about the history than some of the prosecutors and investigators.

They were still trying to untangle the crimes of the Nazis.

They were still trying to untangle the crimes of the Nazis.

Add in the complications of the Iron Curtain for access to documents and to the actual places where most of the Nazi crimes had taken place. There was often cooperation, but it sometimes lacked official sanction or support.

In addition, German politicians worked to place legally place more and more perpetrators out of reach by altering the laws themselves. In the founding document of West Germany, a statute of limitations of 15yrs for manslaughter and 20 for murder was instituted, starting in 1945.

This meant that all Nazis charged with these crimes would need to be prosecuted by 1960 and 1965, respectively.

In the 1960s, amidst worldwide civil unrest, liberals in Germany began challenging this handcuffing of prosecution.

In the 1960s, amidst worldwide civil unrest, liberals in Germany began challenging this handcuffing of prosecution.

Working against this was also the Cold War desires of the US and others to bring West Germany on board as a partner against the Soviets.

War crimes investigations were...embarassing.

Some, like Lidell-Hart went so far as to ask for clemency for some of the worst criminals.

War crimes investigations were...embarassing.

Some, like Lidell-Hart went so far as to ask for clemency for some of the worst criminals.

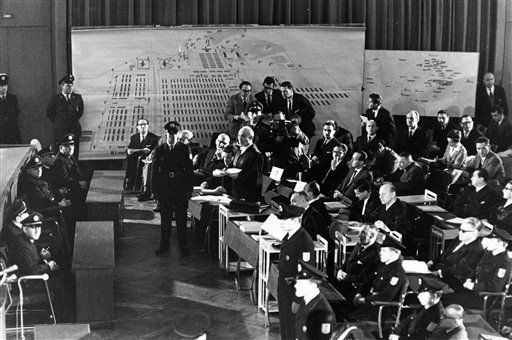

The 1958 Ulm Einsatzgruppen Trial and the Eichmann Trial reminded people that there were plenty of war criminals at large and that their continued freedom was a travesty.

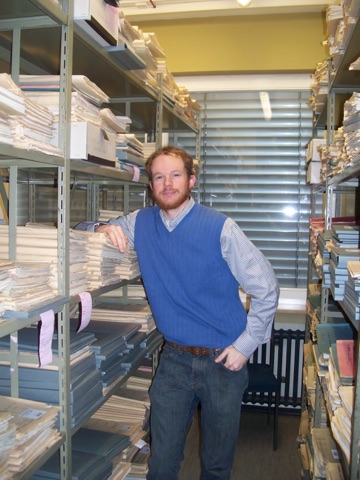

1958 was also an important year as it marked the establishment of the Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crime in the small baroque town of Ludwigsburg outside of Stuttgart.

(I& #39;ve spent many months there in its archives. It still investigates.)

(I& #39;ve spent many months there in its archives. It still investigates.)

The attorneys and investigators in Ludwigsburg fought to open investigations on as many potential perpetrators as possible as the opening of an investigation stopped the statute of limitations clock.

In the German legislature, the statute of limitations was extended several times, and ultimately, removed in 1979.

BUT...and this is a big "but," it pertained only to first degree murder.

BUT...and this is a big "but," it pertained only to first degree murder.

This placed lesser crimes like manslaughter and accessory to murder out of play after 1960. THIS was a critical blow to attempts to prosecute war criminals, again, due to the reliance on pre-war law.

One of the distinguishing factors for murder under that law was the element of "base motives."

Essentially, this required demonstrating not just the act of killing but that it had been excessively brutal, driven by racism, etc.

Essentially, this required demonstrating not just the act of killing but that it had been excessively brutal, driven by racism, etc.

Simply shooting thousands under orders, for example, was not considered "excessively brutal."

Instead, prosecutors now had to prove the mindset of the killer which was infinitely more difficult...on top of the already considerable challenges they faced.

Instead, prosecutors now had to prove the mindset of the killer which was infinitely more difficult...on top of the already considerable challenges they faced.

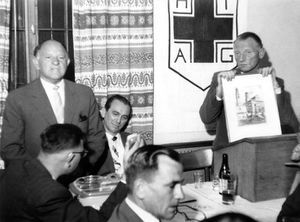

In addition, throughout the period of postwar German trials, underground (and not so underground) self-help organizations existed to provide legal counsel and protection for former Nazis.

Some lawyers specialized in defending these clients.

Some lawyers specialized in defending these clients.

Naturally, one of the understood instructions was to make so statements that indicated antisemitic beliefs or other "base motives."

All of these elements combined to make prosecution of former Nazis after the war incredibly difficult, and that is assuming those involved were actually motivated to do so in the first place.

It is only very recently, with the cases of people like John Demjanjuk and Oskar Groening that German legal precedent has shifted to allow for the prosecution of perpetrators based on simply their participation in the machinery of murder. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-42698558">https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/worl...

So, that is a lot, but hopefully helps to explain some of the history. It is not, of course, an apology for the failures of the German legal system but rather an example of the complexities of history, politics, memory, and justice. https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/the-german-judiciary-failed-approach-to-auschwitz-and-holocaust-a-988082.html">https://www.spiegel.de/internati...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[Thread] Postwar German prosecution of NazisI was inspired by @nath4nglx to do this explainer on the ins and outs (and ups and downs) of postwar Nazi trials. It& #39;s a really interesting look into #History, memory, the #Holocaust, and the law. Enjoy! [Thread] Postwar German prosecution of NazisI was inspired by @nath4nglx to do this explainer on the ins and outs (and ups and downs) of postwar Nazi trials. It& #39;s a really interesting look into #History, memory, the #Holocaust, and the law. Enjoy!](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EiYLfAaWAAAe7MQ.png)

" title="This meant that German police and German district attorneys would investigate and try war criminals. Theoretically, this would be possible due to the continuing efforts of "denazification" begun by the Allies and continued in the Spruchkämmer process.Leni Riefenstahl, 1952 https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="This meant that German police and German district attorneys would investigate and try war criminals. Theoretically, this would be possible due to the continuing efforts of "denazification" begun by the Allies and continued in the Spruchkämmer process.Leni Riefenstahl, 1952 https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Rückhand Zeigefinger nach unten">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>