Admit it. You’ve always intended to get to grips with Atriplex and Chenopodium, but somehow you just never got round to it. The time has come. The fruits are ripe and there are no more excuses. We’ll start with the species that you can do by jizz alone, in the field.

Starting with the easy Atriplex. There are two shrubby ones and two annual herbs. The native shrubby one is A. portulacoides. This is a a locally dominant sprawling plant of saline mud and sand, with lower leaves opposite. It is often flooded at high tide.

The alien shrubby one is Atriplex halimus. This is a tall alien shrub (up to 2.5m) planted as a seaside windbreak and occasionally naturalized. It has all of its leaves alternate.

The easy Atriplex that are annual herbs would never be mistaken for one another. The slender seaside plant with grass-like greyish leaves is A. littoralis. This is also found in towns and by salted main roads (it is one of the less common, so-called ‘salt adventives’)

The other easy annual Atriplex is often completely purple: this is Garden Orache (A. hortensis). It can grow very tall (up to 2m) and it has triangular, truncate leaves.

The best way to get started with the challenging Atriplex species is to go out and find A. prostrata and bring home a specimen. Needless to say, Sod’s Law is at work here, because you need ripe seeds and also basal leaves (these typically wither before seed set, so look around)

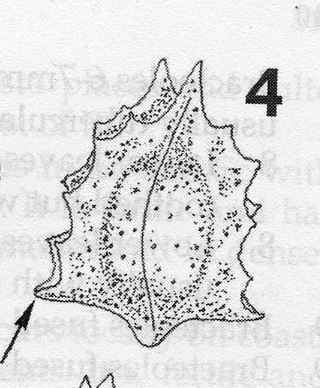

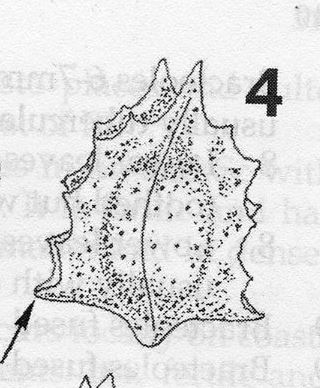

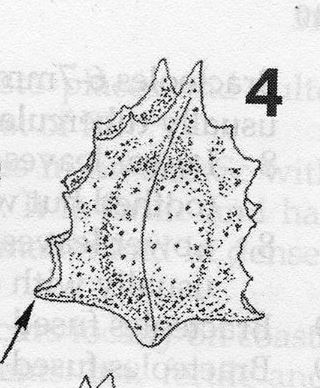

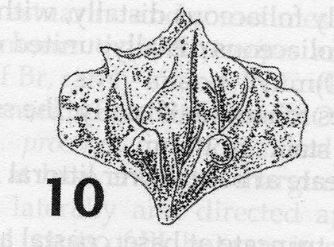

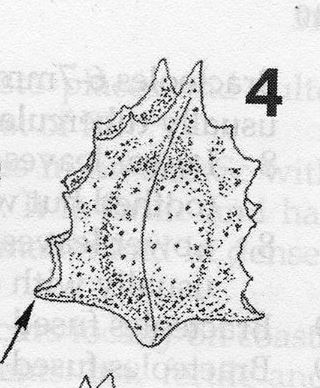

It is basically a matter of unfamiliarity. You are used to looking at species that have obvious petals and sepals and where the seeds are in fruits that are easy to open up and explore. The fruits of Atriplex are hidden inside tissues known as bracteoles (below is A. prostrata)

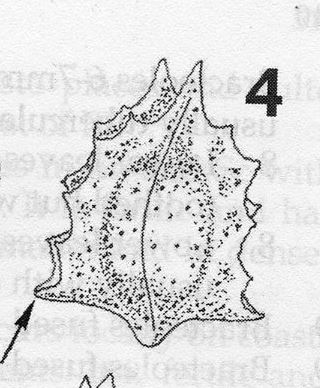

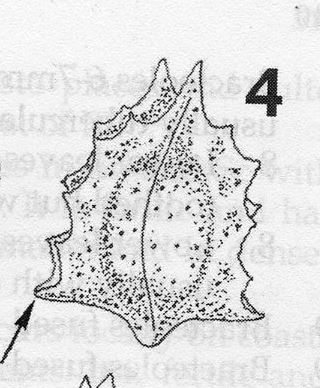

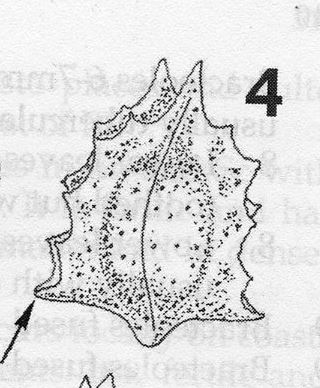

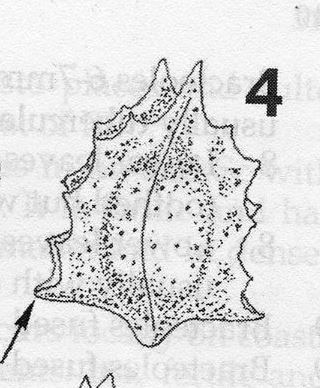

You need to learn how to find your way around a bracteole. Have a close look at your specimen (x10) and find where the two parts of the bracteole are fused, and where they are open. This is indicated by the arrow for A. prostrata (below)

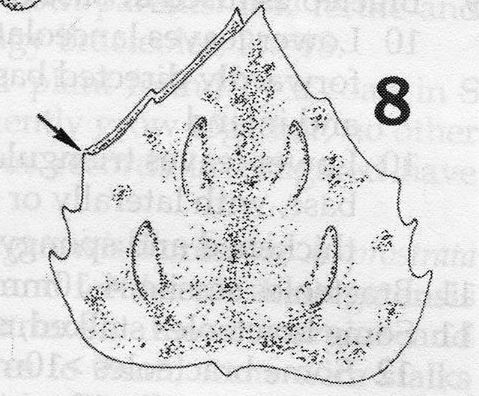

To make this idea more obvious, compare your Atriplex prostrata which has its bracteoles fused only along the base (left) with a different species where they are fused to roughly halfway up the side (right). Once you see this distinction, you’ve cracked it.

The other thing that’s a bit tricky at first is understanding the texture of the base of the bracteole. Is it hardened and cartilaginous (left) or is it herbaceous or spongy (like your specimen of A. prostrata. right) ?

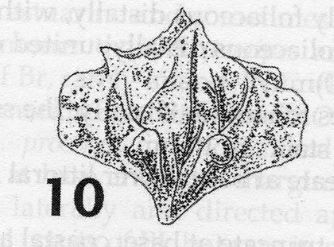

OK. Let’s practice by keying out your specimen (which we fervently hope really is Atriplex prostrata !). Is it a shrub or a herb? Good start. Next, does the bracteole have 3 apical lobes 2 bigger, rounded and diverging, 1 smaller central lobe (left) or not (right) ? Clearly #4

Next, are the bracteoles papery and only on some female flowers (left) or angled and toothed on all the female flowers (right)? Clearly angled and toothed.

Next are the bracteoles hardened at the base (left) or herbaceous (right). Tricky this one, I know. But give your specimen a poke with a needle. It should be yielding (i.e. herbaceous).

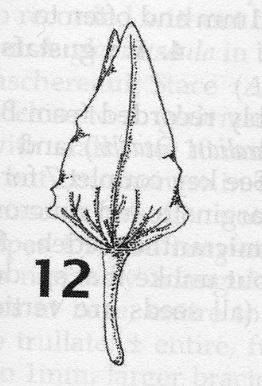

Now a refreshingly easy question. Is your plant Atriplex littoralis (illustrated) with parallel-sided, grass-like leaves ?

No it isn& #39;t.

No it isn& #39;t.

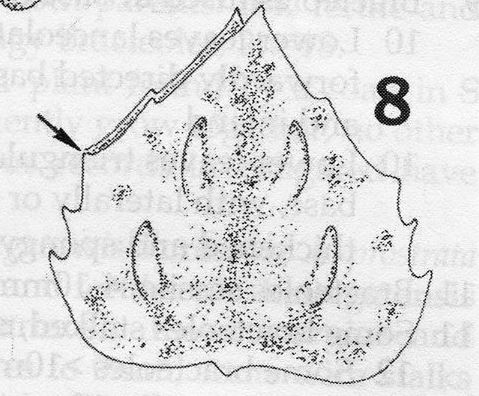

Now comes the really critical question. Are the bracteoles fused for more than 1/3 of their length (left) or fused only at the base (up to 1/4 of their length, right) ? Clearly #4 not #8

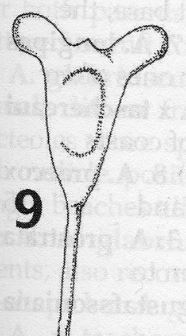

Another simple one next. Measure the length of the bracteole and its stalk (to the nearest mm) using your x 10. Are both long (20 and 10mm respectively; left) or not (< 8 and 0; right) ? Both are short, clearly.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter