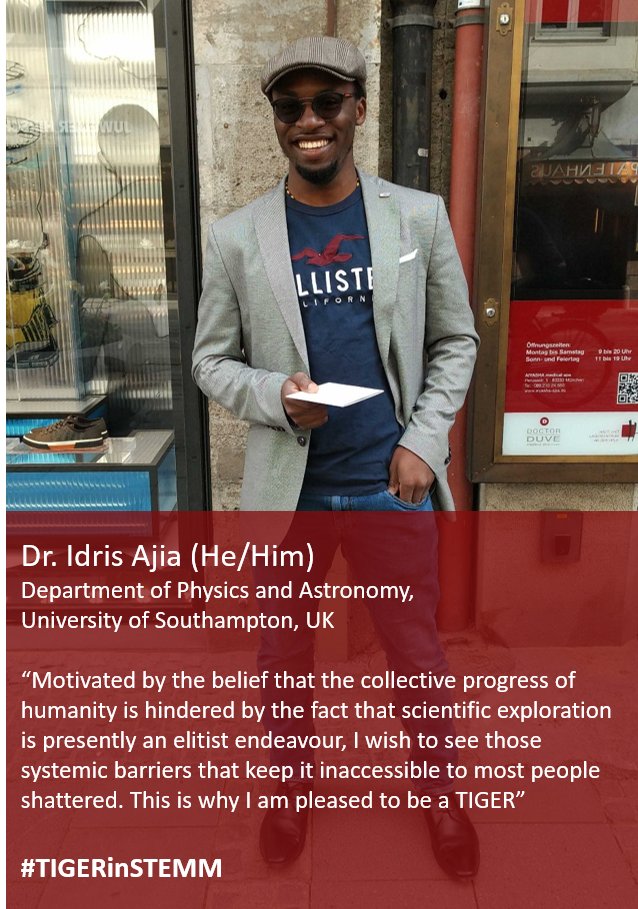

1) Hi, I& #39;m Dr. Idris Ajia ( @idrismonsur), A Nigerian. I presently work as a postdoc at Uni. Southampton. It’s hard to describe myself with words about who I am, where I’m from, what I do. They never satisfactorily encapsulate my story. Might suffice to say I am an academic nomad.

2. Today, I will talk about immigrating to the UK as a scientist, then share some of my perspective on the & #39;legalised human& #39; and why society should aspire for a borderless world. I googled & #39;legalised human& #39;, but the results were far from my meaning. Some were pretty weird too.

3. So, I guess I have to define what I mean: I would define a legalised human as someone whose ability to participate in society is predicated on them meeting certain man-made standards, which then earns them the right to legally participate in said society.

4. Almost every human has an intrinsic need to partake in society. So, setting standards for participation strikes at the core of the definition of humans as social creatures. To decide if someone is qualified to participate in society, is essentially to decide on their humanity.

5. I was born in Jos, Nigeria, into a relatively comfortable middle-class family, whose fortunes only got better over time. This means I have been fortunate enough to be formally educated to the extent of earning a PhD degree. I now work as a postdoc in integrated nanophotonics.

6. It is qualities such as education level, job prospect and income that are used to determine people& #39;s social worthiness. Qualities which my privileged background has conferred on me. These qualities are indicators of my ability to make net economic contributions to society.

7. My route to becoming a legal human in the UK entailed first having a job offer that pays above a certain threshold. After, I had to fill a long application form, answering tedious questions. One of the questions inquired about the date of my most recent visit to a UK hospital.

8. I would never have recalled the date of a visitation that occurred 10 years ago, so I only entered the year, which left me very anxious. This might seem inconsequential to some, but when you consider that I had to cough up a non-refundable ~1,000 GBP visa fee…

9. …and the possibility that my visa application might be rejected on account of incomplete information, you might understand why I was worried. In addition to this, I also had to pay a 400 GBP health surcharge, which is at least refundable.

10. If my visa was rejected, would it mean I would have been unworthy of participating in Southampton society for forgetting a date? What if I forgot the year, and I left that part blank? Thankfully, my application was successful, so I booked a flight for Jan of 2019.

11. Arriving travellers always get scrutinised by border agents. Some nationalities, more than others. As a black person and a Nigerian, this is the bit of travelling I dread the most. The scrutiny always gives me hostile vibes, so I always get very apprehensive at this stage.

12. I handed my passport to the border agent at Heathrow. Despite having been legalised by the visa, I was still met with a barrage of questions: "What are you doing here?", "How long do you plan to stay?", "What do you do?", "What is photonics?", "Explain your research?".

13. Imagine being asked to explain your research by an immigration officer after a long and tiring flight, even as you struggle to suppress all hints of the apprehension you feel, because you just know that they are not so much interested in what you say as in the way you say it.

14. There are worse experiences yet. An Arab friend was asked if he knew any UK imams, and how regularly he prayed by a border agent at Manchester airport. Was his worthiness to participate in UK society hinged on the imams he knew and how regularly he prayed?

15. It can be rather demoralising and humiliating to have to justify your humanity to another human, because they have the authority to deem you illegal, based on how you respond to some arbitrary set of questions. Sadly, there are worse experiences yet.

16. I have to mention people in even more desperate situations. I wonder how hard it must be to uproot one& #39;s self from their homes, pay thousands of pounds to smugglers, risk one’s life and those of one’s kids, to cross deserts on foot, seas and channels in dinghies…

17. …only to then be seen as illegal humans by powerful members of society. For our common humanity, I have to reject any notion that an accident of birth which situated me in better fortune, somehow makes me more worthy of participation in society than them.

18. I wonder about the violence inherent in the words with which we classify people: migrants, illegal immigrants, undoc. I wonder about the violence of the abstract lines with which we separate each other. Do these not just create hierarchies of humanness and social worthiness?

19. Do they not permit us to tolerate the violence inflicted on those we& #39;ve arbitrarily decided aren& #39;t human enough? Do they not restrict our collective empathy to an & #39;approved& #39; group? Do they not dehumanise us just as surely as they dehumanise the other?

20. It is for these reasons that I believe all societies should aspire towards a borderless world. A borderless world would be one in which our humanity isn& #39;t confined to lines on a map. One in which human cooperation is a measure of progress and development.

21. One which acknowledges how deeply intertwined our fates are. One in which we& #39;re more concerned about the welfare of the boy in the cobalt mines of Congo, or the girl in the sweatshop in India, than we are eager to profit from their sweats.

22. On this note, I will conclude with this question: If we have managed to build a world in which the products of human labour see no boundaries, why isn& #39;t one with boundless empathy possible?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter