#NTiHoR 1/15 Before the railways was the carrying trade—an intermodal network of waggons, boats and coastal ships operated by independent carriers. Historians have written about these transport modes, but the integrated carrying system is less well understood.

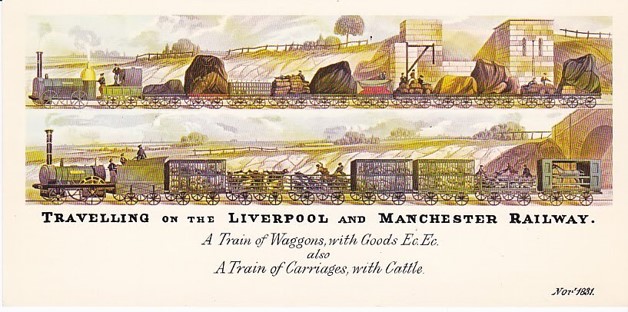

#NTiHoR 2/15 It was within this carrier system that rail lines first appeared, as adjuncts to canals or coal mines. The former lines operated like canals (users paid tolls); the latter were owned and operated by mine owners.

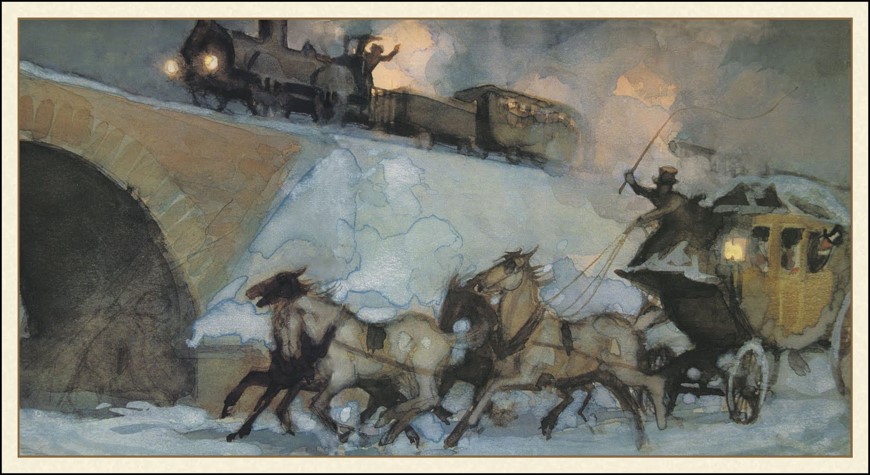

#NTiHoR 3/15 In the 1830s the first railway companies promised investors profits from tolls on goods carriage, but soon focused on far more profitable passenger travel. Wherever a rail line was built, coaching disappeared as rail travel was a clear improvement.

#NTiHoR 4/15 However, this was not true for rail goods transport which was more expensive, riskier and less convenient than the carrying trade; often faster, but speed wasn’t necessary for customers of carriers (time-sensitive goods went by coach and later passenger train).

#NTiHoR 5/15 An 1839 report showed that railway companies used four goods carriage business models: contracting with carriers, running trains for carriers, running both carrier and company trains, or running company trains only, excluding carriers.

#NTiHoR 6/15 The Liverpool & Manchester Railway provided waggons for carriers like Hargreaves, Harrisons and Pickfords as well as offering its own goods transport service. Of the 11 companies reviewed in 1839 only two had company-only goods carriage.

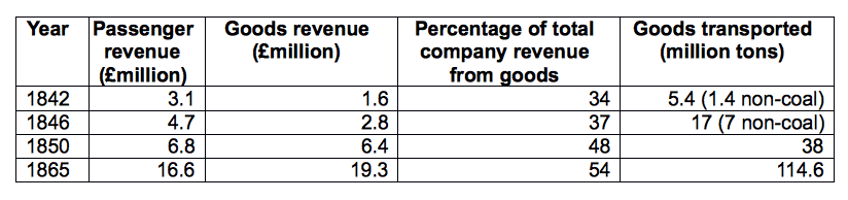

#NTiHoR 7/15 In 1842 railway companies made about 1/3 of their revenue from goods and carried about 1.4M tons of non-coal goods. By 1850 nearly half came from about 28M tons of goods. By 1865 nearly 115M tons of goods provided 54% of revenue.

#NTiHoR 8/15 These figures suggest something obvious to many at the time—rail goods service was so much less profitable than passenger service that it was subsidised by passenger profits. Thus companies’ change in focus from passenger to goods provoked heated internal debate.

#NTiHoR 9/15 Although it was clear that companies made more profit working with instead of excluding carriers, rail company monopoly carrying prevailed. Why? Risk control, vertical integration, personalities of Mark Huish and Braithwaite Poole of the Grand Junction Ry Co.

#NTiHoR 10/15 While the railway companies soon united in excluding carriers, the policy was opposed not only by carriers but also customers, courts and government. The ensuing conflict was known in the press as the ‘carrying question’.

#NTiHoR 11/15 A series of lawsuits carriers brought against railway companies--Pickfords v Grand Junction 1840-1842 and 1844, Parker v Great Western and others, 1844 through the 1850s, Crouch v L&NW and others, 1849--attracted public attention.

#NTiHoR 12/15 RW Kostal describes several of these cases in Law and English Railway Capitalism. Although the carrier plaintiffs won every lawsuit, the railway companies continued their illegal policies and practices.

#NTiHoR 13/15 Huish’s model prevailed on the Grand Junction and on the L&NW after amalgamation in 1846. This was practically the end of carriers on railways. The Ry Clearing House forced conformity with monopoly carrying (George Hudson of the Midland Ry opposed but complied).

#NTiHoR 14/15 In these tweets I’ve argued that while the transition from coach to rail passenger travel was a foregone conclusion, the transition from the carrying trade to railway goods carriage was historically contingent. This change affected the wider economy.

#NTiHoR 15/15 The carrying trade supported distributed multistage production, while the railway network facilitated centralised factory production. Read the whole story here: https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=1&uin=uk.bl.ethos.772970">https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDeta... Thanks for your virtual attention!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter