Anyone thinking about the intergenerational ethics of climate policy should check out @PatrickTBrown31& #39;s thread on his new paper with @KenCaldeira and economist/photographer @jmorenocruz.

I& #39;ll add a few thoughts of my own below. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> https://twitter.com/PatrickTBrown31/status/1306244493583118336">https://twitter.com/PatrickTB...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> https://twitter.com/PatrickTBrown31/status/1306244493583118336">https://twitter.com/PatrickTB...

I& #39;ll add a few thoughts of my own below.

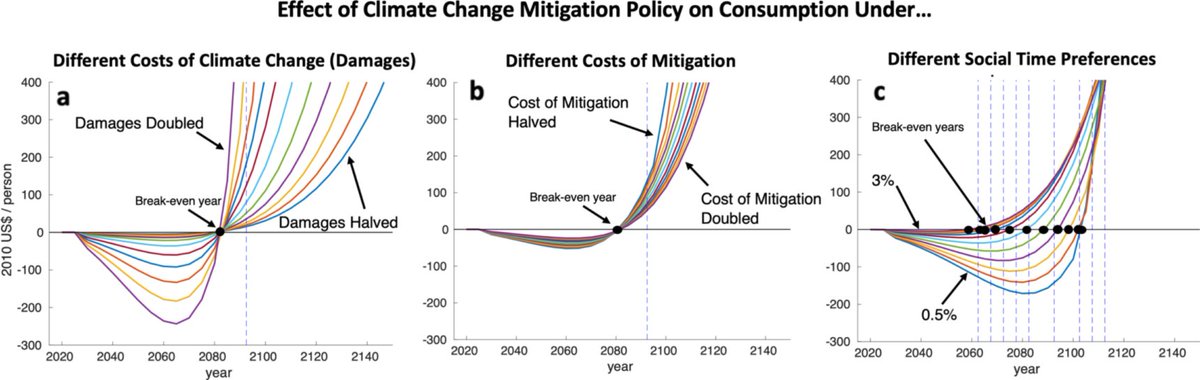

Their paper introduces the idea of the "break-even year: the year when net global per-capita consumption, under economically optimal [mitigation] policy, begins to exceed net per-capita consumption under a no-policy case."

The take-home message is: unless you& #39;re younger than me, you& #39;re not going to live to see the break-even year. Sorry.

Even if the world gets serious about mitigation in the next few years, the break-even year doesn& #39;t come until about 2080 in the model they& #39;re using.

Even if the world gets serious about mitigation in the next few years, the break-even year doesn& #39;t come until about 2080 in the model they& #39;re using.

Note: the authors are NOT arguing against mitigation! Quite the opposite. The point is to illuminate why it& #39;s so hard to overcome what climate ethicist Steve Gardiner calls "the tyranny of the contemporary." Mitigation is short-term pain, long-term gain.

Now, here& #39;s the part that I find most interesting: The paper uses DICE, and a lot of people accuse DICE of badly underestimating damages from climate change. What Brown et al find is that the break-even year doesn& #39;t change when you tweak DICE& #39;s estimate of climate damages!

To be more specific, DICE calculates damages by taking some coefficient, φ, and multiplying it by the square of global warming: φ*t^2.

Nordhaus, who invented DICE, uses φ = 0.00236. This has the...uh...surprising result that 4.5C of warming would only reduce global GDP by ~5%...

Nordhaus, who invented DICE, uses φ = 0.00236. This has the...uh...surprising result that 4.5C of warming would only reduce global GDP by ~5%...

So, one thing you might do is use a larger value for φ. But what Brown et al show is that changing φ doesn& #39;t actually change the break-even year. As they say, though, changing the damage function in other ways might change their results.

Why is that? Basically, if DICE is underestimating climate damages, then it& #39;s also underestimating the economically optimal rate of mitigation. More damage  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="➡️" title="Pfeil nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach rechts">more mitigation

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="➡️" title="Pfeil nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach rechts">more mitigation https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="➡️" title="Pfeil nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach rechts"> higher short-term costs. So the break-even year stays put.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="➡️" title="Pfeil nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach rechts"> higher short-term costs. So the break-even year stays put.

Another thing people dislike about DICE is its relatively high discount rate, which makes long-term gains count for less than short-term losses.

Brown et al show that lowering that discount rate actually pushes the break-even year further into the future!

Brown et al show that lowering that discount rate actually pushes the break-even year further into the future!

Why is that? Because valuing the future more means that economically optimal mitigation requires more mitigation now. If we pay more now, it takes longer to break even.

A final, crucial point: DICE looks at globally averaged impacts. In the real world, climate impacts people unevenly, with those least responsible suffering the most. That suffering provides a compelling reason to mitigate climate change now, even w/o thinking of future people

I hope I haven& #39;t misrepresented anything you said in the paper, @PatrickTBrown31, @KenCaldeira & @jmorenocruz. Please correct me if I have. Also interested in @kelleher_& #39;s thoughts (as always).

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter