Q: Why is it so difficult to motivate global society to implement greenhouse gas emissions reduction policies if these policies confer not only environmental but also economic benefit? One reason is near term costs. New paper with @KenCaldeira @jmorenocruz https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2515-7620/abb413">https://iopscience.iop.org/article/1...

To elaborate, one potential reason for the difficulty in implementing “economically optimal” greenhouse gas emissions restrictions is that these plans are probably not economically beneficial for the generation of people that launch them.

Climate economists are familiar with this but it is less appreciated by the broader research community and the public. We explore this issue in our new paper “Break-even year: a concept for understanding intergenerational tradeoffs in climate change mitigation policy” link above.

Potential solutions to climate change are often framed as a tradeoff between reducing humanity’s impact on the environment on one hand and harming the economy on the other.

More specifically, it is thought that we can reduce our climate change-related impact by imposing a global price on carbon that results in an increase in the price of energy which entails a reduction in production and consumption.

Under this framing, it is natural for people to strongly disagree about climate policy prescriptions since individuals will inevitably diverge in the relative value they place on environmental vs. economic concerns.

However, the issue of whether or not it is in humanity’s collective best-interest to reduce greenhouse gas emissions may not be as complicated and subjective as the above framing makes it seem.

In fact, it has been consistently calculated for decades that the “economically optimal” greenhouse gas emissions pathway is one of immediate restraint, followed by consistent reduction to net-zero emissions within about a century or sooner.

Despite this, climate change mitigation policy has been notoriously difficult to implement at the global level even with a United Nations Convention (UNFCCC, 1992) long dedicated to doing just that.

This gives rise to an apparent paradox: Why is it so difficult to motivate global society to implement greenhouse gas emissions reduction policies if these policies confer not only environmental but also economic benefit?

One well-studied reason is related to the so-called tragedy of the commons where each country/individual appreciates that it is in their own best-interest not to reduce their emissions despite it being in the global best-interest to do so.

An intergenerational version of the tragedy of the commons, that we investigate in our paper, has to do with WHEN emissions reduction policies would become economically beneficial.

There has been a great deal of discussion in the literature regarding how to weigh the wellbeing of different generations in the context of climate policy which has played out largely in debates over the discount rate.

Despite this vigorous discussion on trading off the wellbeing of current vs. future generations, we have found that the specific point in time for which policy begins to confer net benefits to society is rarely highlighted.

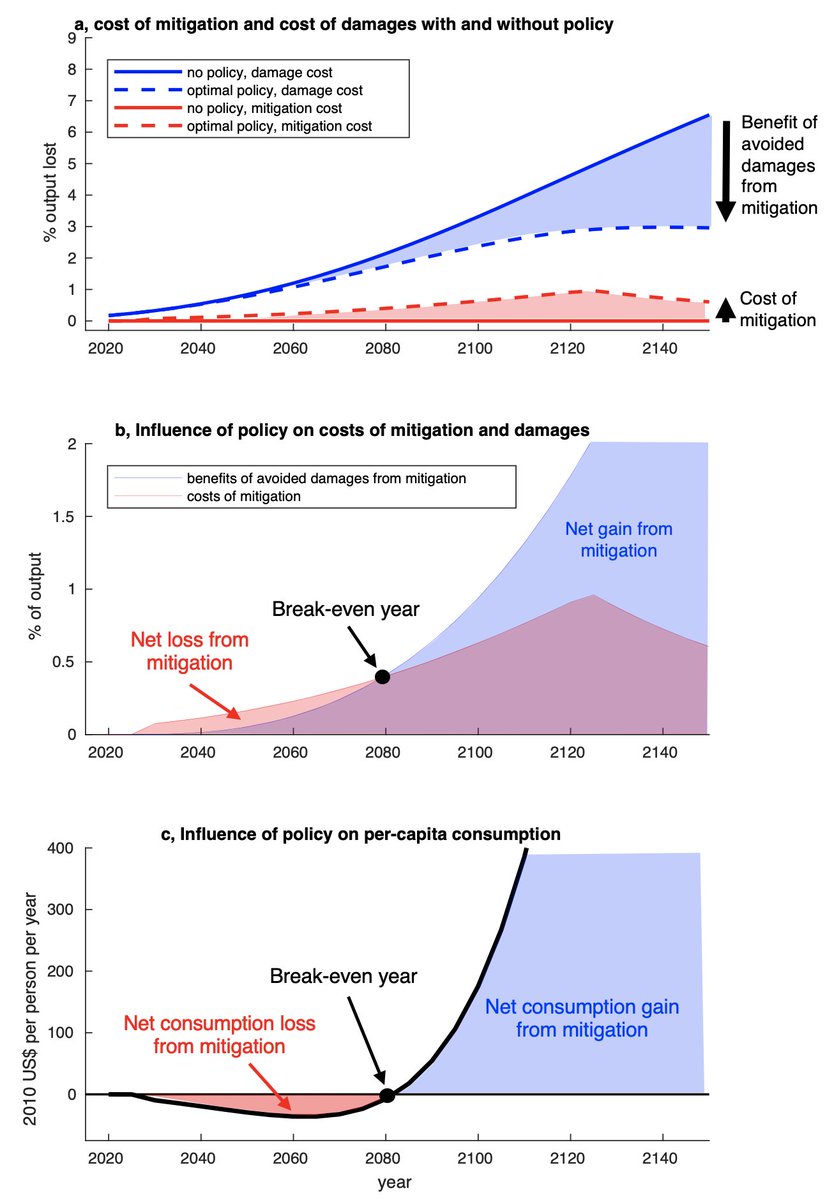

The purpose of our article is to explore this issue by focusing on the concept of the break-even year, which we define as the year when the economically optimal policy begins to produce global mean net economic benefits.

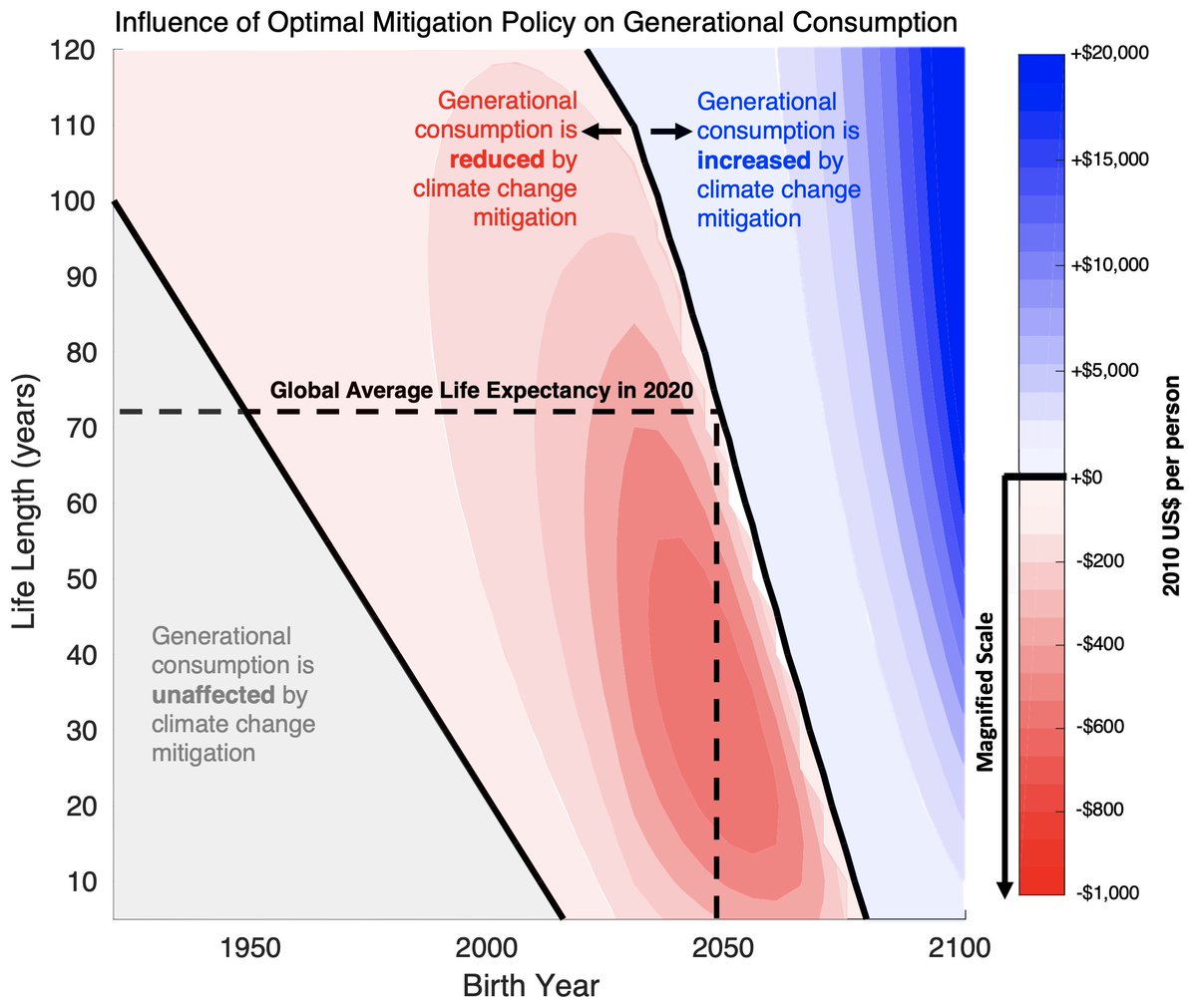

We show that in a commonly used climate-economy model (DICE), the break-even year is relatively far into the future – around 2080 for mitigation policy beginning in the early 2020s.

This means that If average life expectancy (∼72 years in 2020) does not change substantially, the global generation born near the middle of the 21st century (∼2050) would be the first to experience cumulative economic net benefit from climate-change mitigation policy.

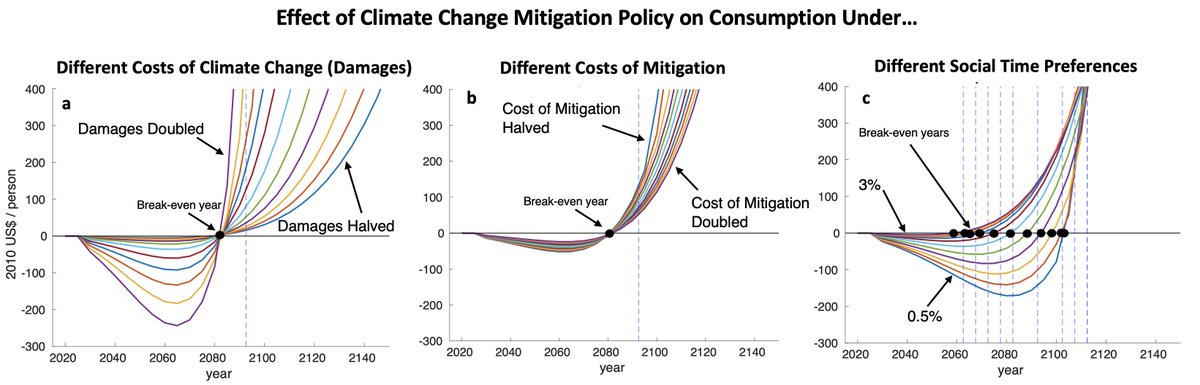

Notably, the break-even year is not sensitive to the uncertain magnitudes of the cost of mitigation or the economic damages from climate change. This result makes it explicit and understandable why an “economically optimal” policy can be difficult to implement in practice.

Our purpose is to bring this important issue to the foreground in order to stimulate discussions of potential solutions. Regardless of the specific solution to this problem we believe that in order for it to be overcome, it should be grappled with explicitly rather than obscured.

One way to potentially overcome some of the above barriers would be to emphasize the air-quality cobenefits

of climate change mitigation which tend to be more salient than climate impacts and they are experienced locally in both space and time.

of climate change mitigation which tend to be more salient than climate impacts and they are experienced locally in both space and time.

Thus their alleviation represents a benefit that is not subject to the same long delay that the climate-related benefit would be and they are benefits that could be appreciated within a term of a politician.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter