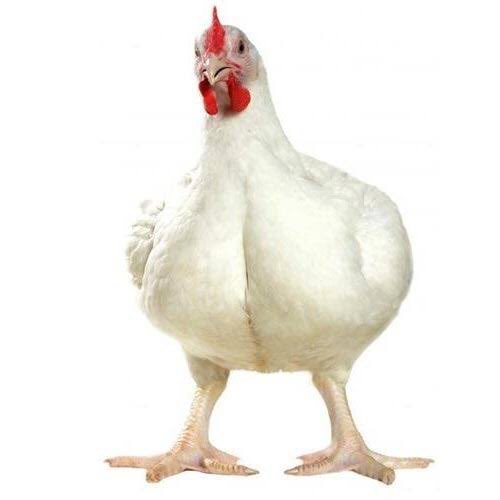

Before 1948, chicken wasn’t a mainstay of the dinner table. A contest to breed a bigger, better bird changed that.

In 1925 there were more than six million farms in the United States, compared with two million now. They were mostly small properties, growing a mix of crops and animals, and they almost all raised chickens.

Which type of chicken was a complicated question, because there were so many to choose from.

The January 1921 issue of the American Poultry Journal carried six pages of small-type classified ads featuring dozens of varieties from hundreds of breeders nationwide.

The January 1921 issue of the American Poultry Journal carried six pages of small-type classified ads featuring dozens of varieties from hundreds of breeders nationwide.

Single-Comb Anconas, Silver Wyandottes, Brown Leghorns, Black Langshans, Light Brahmas, Sicilian Buttercups, Golden Campines, White-Laced Red Cornish, Silver-Gray Dorkings, Silver-Spangled Hamburgs, Mottled Houdans, Mahogany Orloffs, White Minorcas, Speckled Sussex.

Most farms kept small flocks, from a few birds up to about 200, and for most of them, the point of chickens was eggs; birds were sold for meat only when hens were spent or when chicks hatched out male.

Farmers chose the variety they raised based on what other farmers in their area preferred—breeds that had adapted well to whatever wet or dry, windy or humid conditions prevailed where they lived—or because they were persuaded by boastful ads

that talked up the egg production of breeds that won medals at state and national poultry expositions.

Chicken production’s first step on the road to innovation, and the expansion that followed it, came in 1923 with the first electrically heated incubator.

Chicken production’s first step on the road to innovation, and the expansion that followed it, came in 1923 with the first electrically heated incubator.

That freed farmers from having to choose and maintain breeding stock, and also from losing the months in a hen’s short productive life when she would be hatching her eggs instead of laying more.

Now they could outsource those tasks to a new tier of the industry,thousands of hatcheries ship newborn chicks by mail.But the breeds those chicks came from were still selected for maximum egg production,not for any eating pleasure they might offer after their laying years ended

Choosing birds for how many eggs they could lay was a smart strategy through the privations of the Great Depression and the restrictions of World War II: It maximized the protein you could get from a bird without sacrificing the bird herself.

But after the war, when beef and pork emerged from rationing, eggs seemed dull by comparison, and laying hens’ lack of tasty muscle made them an insufficient alternative. People had willingly cut their meat eating for a long time, to support the war. Now they wanted to indulge.

https://api.nationalgeographic.com/distribution/public/amp/environment/future-of-food/poultry-food-production-agriculture-mckenna">https://api.nationalgeographic.com/distribut...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter