Alright, so here’s the start of a series of threads on the French army in the 18th century. Today’s thread will be introductory in nature and provide some background on the shift from 17th century warfare to 18th century warfare and the military reforms of Louis XIV.

Expect new additions to the thread series every weekend (my schedule permitting) if people seem interested. The next thread will be on the War of the Spanish Succession and maybe the War of Austrian Succession as well (though that might be overly optimistic).

This thread (and the others in the series) probably won’t be too useful to experts on the subject matter, but I hope it’s a good introduction for everyone else. Also, I can’t really cite sources on here, so feel free to ask where I’m getting information and for further readings.

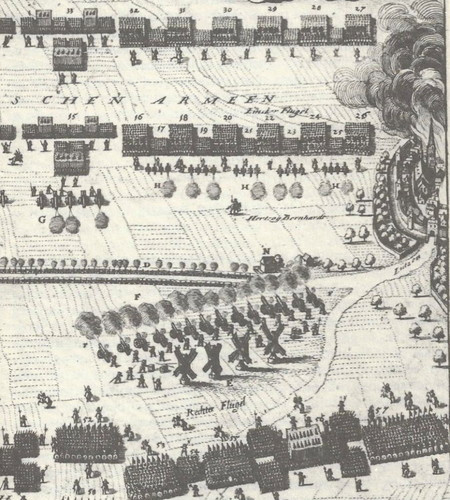

So, we’re going to start with a bit of background on how war was fought in the 17th century. The 17th century was the tail-end of the pike and shot era. Basically, musketmen did most of the killing, but needed to be protected by pikemen from cavalry. In early pike and shot

warfare this lead to the creation of massive pike squares with intermixed musketmen due to the predominance of cavalry. Hopefully useful reference image below. However, these massive blocks were unwieldly to say the least. Also, artillery was becoming far more common and mobile.

A densely packed block of hundreds of men is perhaps the last place you want to be when facing cannons, so generals naturally evolved their formations. The squarish blocks were elongated to reduce casualties from enemy fire and increase the formation’s firepower.

Over time, generals like Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus decreased the numbers of pikemen in their formations and made them more linear for the above-stated reasons. These reforms were generally copied by militaries across Europe.

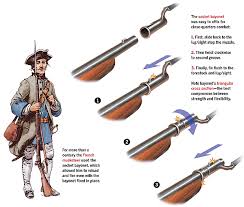

By the end of the 17th century, the widespread use of the bayonet and the flintlock musket (which was more reliable and faster to load than its matchlock predecessor) only furthered the decline of the pike. By the end of the 9 Years’ War (1697) both inventions were in wide use.

A few notes about bayonets: Bayonets were an intentional attempt to replace the pike and give musketmen more staying power in melee (particularly against cavalry). However, the first bayonets, plug bayonets, had some serious issues.

Plug bayonets were directly inserted in the muzzle of the musket, meaning one couldn’t fire the musket and have a bayonet attached. At the Battle of Killiecrankie Williamite forces were overrun by Jacobite highlanders because they didn’t have time to fix bayonets before contact.

This flaw was somewhat overcome with the development of the ring/socket bayonets, though early on bayonets had a tendency to fall off of muskets in the heat of battle. Regardless, having musketmen with bayonets was far preferable to having dedicated contingents of pikemen.

By the War of the Spanish Succession most infantrymen of the major combatants were armed with flintlock muskets, which will be the main firearm of European infantry for the rest of these threads. In battle, the average rate of fire was usually around 2-3 rounds per minute.

By the 9 Years’ War, most regiments were drawn up in line formation (usually three men deep) for battle and column formation for marching. There will be exceptions to this during the 18th century and debates about ideal battle formation, but we’ll get back to that later.

Another thing I should emphasize is that battles weren’t particularly common. Campaigns were generally determined by maneuvering and sieges. Battles were risky/expensive and conventional wisdom favored the defensive over the offensive. Thus, generals were usually cautious.

Now, the state of warfare will occasionally change in the 18th century, particularly when a general or monarch is unusually aggressive with their forces. Even then, it usually takes two armies to make a battle, and a competent general could usually avoid battle if he wanted to.

So, on the battlefield the French army wasn’t that different from other armies of the period. Its advantages came from its organization, which was far superior to that of most of its opponents in the second half/quarter of the 17th century and the early 18th century.

Now this is not to say the French army was bad qualitatively, it wasn’t. Some of its regiments were arguably the best in Europe (particularly France’s Irish and Scottish regiments). But this wasn’t the Swedish army, they didn’t rely on tactical prowess to make up for numbers.

The military reforms of Louis XIV (r.1643-1715) coincided with far-reaching economic and societal reforms that increased centralization and integrated the nobility into the state. Louis XIV’s reforms could have their own dedicated thread, but the next tweet will have to suffice.

The chain of command in the French army was generally clear. Its troops were paid on time and many were members of regiments that remained standing during periods of peace. French logistics were also usually semi-efficient. The same could not be said of any other army of the day.

France was also the most populous European state at the time and this, combined with a semi-efficient bureaucracy, allowed France to field massive armies on multiple fronts. In the 1690s the French army was around 400,000 men (making it the largest army in Europe since Rome).

Louis XIV was also incredibly lucky to have brilliant commanders for most of his reign. Early on he had Turenne and the Grand Condé, later he had Luxembourg and Villars. The officer corps itself was decent, with good service generally being rewarded.

However, the French army was certainly not perfect. By 1700 many experienced officers had retired. Positions were sold to the highest bidder, which meant new officers were of unknown quality. At the tactical level, its cavalry relied too heavily on its limited firepower.

None of these defects were particularly serious and were common in other armies. However, over time the officer corps, which relied heavily upon a competent monarch and ministers to promote officers based on merit, would gradually rot and decline.

But that’s a story for another thread. Next time we’ll be covering the War of the Spanish Succession, where the French army will face one of the best commanders in European history and loose its aura of invincibility (but prove itself an incredibly resilient fighting force).

Oh no, lose* not loose. I& #39;m sure there are other typos in my thread. My apologies.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter