The European Union has one of the better policies on protection from sexual violence in conflict and the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, yet fuels the mass incarceration of migrants in conditions where sexual violence is rampant.

How? A thread. https://academic.oup.com/ia/article/96/5/1209/5901383">https://academic.oup.com/ia/articl...

How? A thread. https://academic.oup.com/ia/article/96/5/1209/5901383">https://academic.oup.com/ia/articl...

Since before the ‘refugee crisis’ (the crisis of being a refugee; the crisis of responsibility and solidarity in response to displacement), Europe has practiced bordering at a distance, initially pushing back people crossing the Med, and then empowering others to pull them back.

The effective extension of the EU border zone into the Med involves a jurisdictional reorganisation of the sea but also a containment strategy that outsources confinement and deportation to the presumptive Libyan authorities, which receive significant training and resources.

The cruelty and lethality of bordering at sea have been much analysed, increasingly with a forensic detail that is hard to stomach: #toggle-id-3">https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/seawatch-vs-the-libyan-coastguard #toggle-id-3">https://forensic-architecture.org/investiga...

(here I pause to mention the work of Maurice Stierl, Martina Tazzioli, and Polly Pallister-Wilkins from whom I have learned so much in working on this grim topic over the last year)

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/anti.12320

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/1... href=" https://academic.oup.com/migration/article/4/1/1/2413390

https://academic.oup.com/migration... href=" https://academic.oup.com/ips/article/9/1/53/1845863">https://academic.oup.com/ips/artic...

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/anti.12320

Less explored by academics are the conditions that await migrants when forcibly returned. The recognised authorities include a Directorate for Combatting Illegal Migration (DCIM) which operates a network of detention sites (too informal and compromised to be called prisons).

(see especially Sara Hamood, who was writing about this early; Luiza Bialasiewicz and Rutvica Andrijasevic; plus analyses of ‘neo-refoulement’ and the externalisation of refugee policy by Nadine El-Enany, Emma Haddad, Jennifer Hyndman and Alison Mountz) https://academic.oup.com/jrs/article/21/1/19/1513290">https://academic.oup.com/jrs/artic...

The vast majority of those in detention were incarcerated following return by the & #39;Libyan Coast Guard& #39;, numbering between 5,000 and 20,000 migrants at any given point between 2017 and 2019, held indefinitely and in conditions that have been repeatedly described as ‘inhuman’.

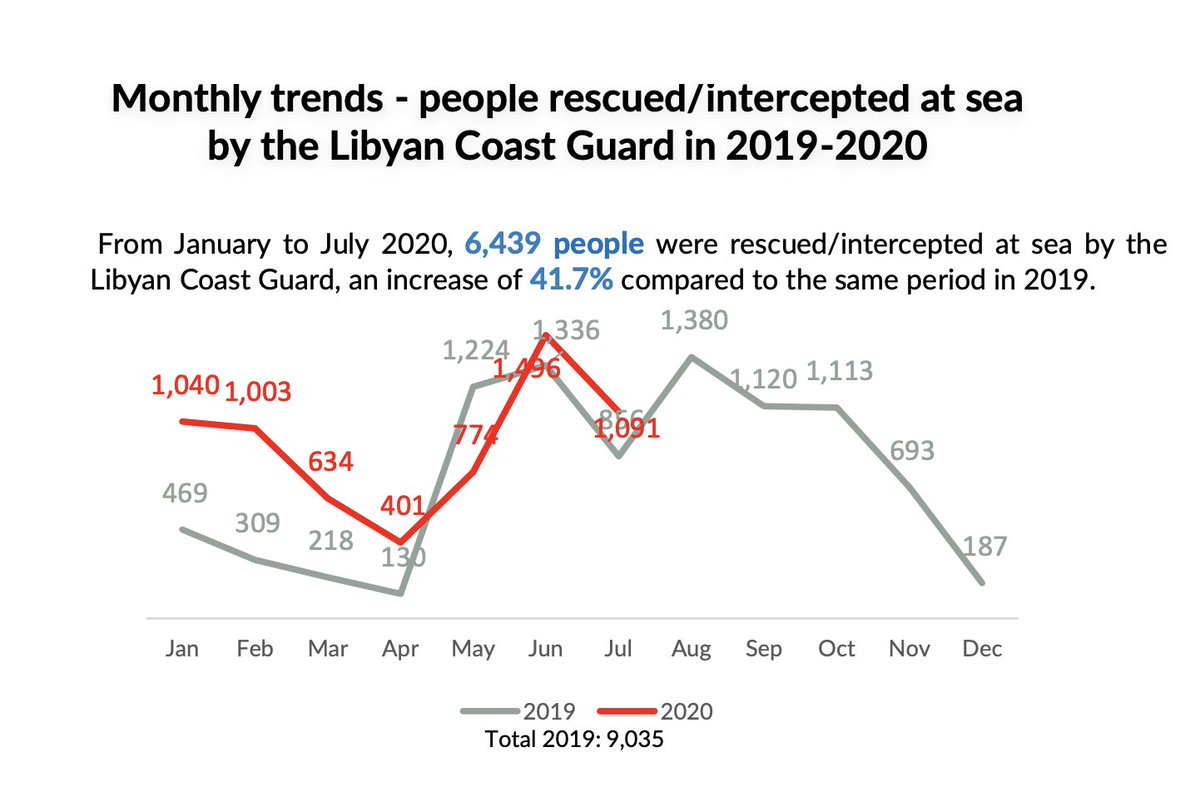

Pullbacks continue to swell the detainee population. Interceptions grew significantly with the more aggressive Operation Sophia and Italian and Libyan ‘codes of conduct’ restricting NGO rescue. 15,000 migrants were captured in 2017 and 2018, 9,000 in 2019, likely more in 2020.

The detail of abuses in detention are nauseating, and the paper contains some necessary detail on scale and prevalence, as documented and affirmed by numerous human rights and humanitarian groups (Amnesty, HRW, MSF, Refugees International) and agencies (UNHCR, UNSMIL, OHCHR).

The crucial point is that official detention facilities are major sites of sexual and gender-based violence in Libya, with clear evidence of abuses dating to at least 2015. Exploitation and abuse are integral to a large and longstanding trafficking–detention–extortion complex.

The evidence has been raised often at meetings between the EU and human rights groups, and according to interviewees has never been contested by EU officials, who agree that detention conditions are horrific.

The evidence of sexual and gender-based violence is publicly available and is among the worst I have read in over a decade of research.

Trigger warning. https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/more-than-one-million-pains-sexual-violence-against-men-and-boys-on-the-central-mediterranean-route-to-italy/">https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-...

Trigger warning. https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/more-than-one-million-pains-sexual-violence-against-men-and-boys-on-the-central-mediterranean-route-to-italy/">https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-...

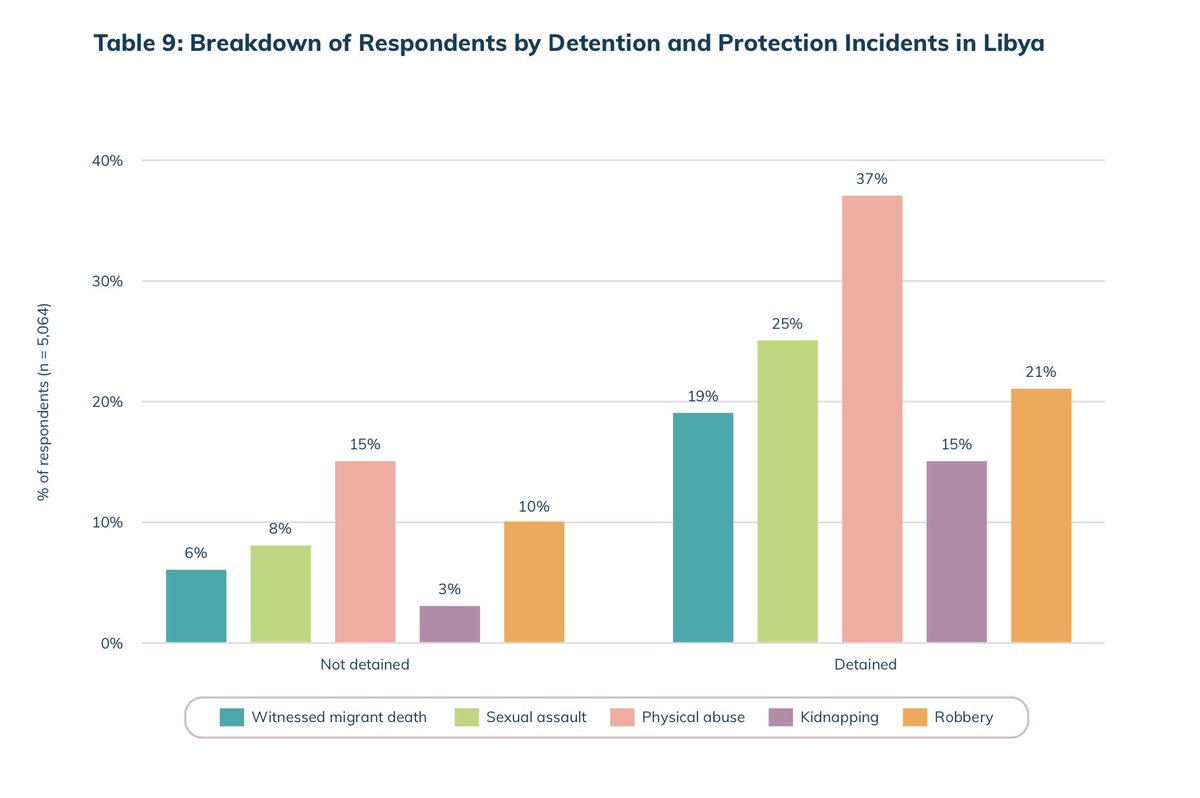

Sexual and gender-based violence against migrants in Libya is widespread to the point of ubiquity, and evidence shows a correlation between detention in official sites and experiences of such violence (whether before or during detention).

Source: http://www.mixedmigration.org/resource/what-makes-refugees-and-migrants-vulnerable-to-detention-in-libya/">https://www.mixedmigration.org/resource/...

Source: http://www.mixedmigration.org/resource/what-makes-refugees-and-migrants-vulnerable-to-detention-in-libya/">https://www.mixedmigration.org/resource/...

These abuses are a logical corollary of the EU& #39;s containment policy, even though the official EU position is that detention sites should be closed, and despite repeated EU and member state pledges to extend protections against sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict space.

As early as 2008, the EU’s Comprehensive Strategy on WPS promised to “shape” EU foreign policy to protect women (not yet all genders) from sexual violence “during and after conflict” and noted migration and asylum as key areas of relevance for implementing the promise.

Migration was also a key priority in the Council of Ministers& #39; 2018 conclusions, which became the current EU WPS strategy, pledging that “‘the WPS Agenda is to be given effect in all EU external action”.

Yet EU officials confirmed to me that there has been no attempt to include WPS commitments within Libya policy. Bureaucratic politics, and a lack of understanding of gender issues on the part of officials with country briefs, were cited as part of the reason.

This extraordinary finding mirrors a point made by @AikoIiris and @DrAudreyReeves, to the effect that once the ‘conflict-affected woman’ leaves the war zone (narrowly conceived), she also crosses a boundary of recognition. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-international-security/article/women-peace-and-security-after-europes-refugee-crisis/F9BEE2FF2DC6FC2BB656A549C23B5E76">https://www.cambridge.org/core/jour...

There is also a resonance here with previous findings on gender equality and mainstreaming practices in EU foreign policy by @MaxineDavid, @RGuerrina, @ToniHaastrup and others, signalled but not pursued as much as I would have liked in the piece.

e.g.: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277539512001082">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

e.g.: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277539512001082">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

The profound disconnect between EU WPS policy and the strategy of pullback and containment has horrifying consequences, and in the paper I explore two dimensions or mechanisms of what I term ‘humanitarian disavowal’.

The first is comparatively well-understood, which is that practical recognition of EU – and EU member states’ – commitments on protection from sexual and gender-based violence is almost entirely displaced by the ‘trafficking’ framework.

EU foreign policy is consistently presented as securing the evacuation of the detained, without mentioning either the pushback/pullback that leads to detention or the numbers still imprisoned. Migrants are seen as ‘at risk’, but nevertheless as beneficiaries of EU action.

As an indication of this disavowal, sexual and gender-based violence issues were mentioned only 9 times (and only 7 times post-revolution) in EU Parliamentary debates on Libya between 2010 and 2019, compared to 170 references to trafficking and criminality in the same period.

At the same time, a second mechanism operates, which outsources protection to agencies “on the ground” like UNHCR, somewhat funded by the EU through a small portion of initiatives principally devoted to & #39;border cooperation& #39;, such as the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.

UNHCR runs a humanitarian evacuation scheme, where the most vulnerable in official detention are identified (including on grounds of vulnerability to gendered harms) and prioritised for resettlement, usually via Niger but now also Rwanda. A tiny number are accepted by Europe.

Yet my interviews confirmed what many advocates have stressed: UNHCR teams face huge constraints in accessing detention sites and conducting interviews, notwithstanding the conceptual politics of attributing ‘vulnerability’; and very few can be evacuated in any event.

Just 289 vulnerable persons were evacuated in the first three months of 2020, of whom no more than 92 were classed as ‘sexual and gender-based violence’ or ‘women at risk’, out of a current population of 48,626 registered refugees or asylum-seekers in Libya. That is not a typo.

By definition, anyone detained in Libya is vulnerable, yet UNHCR staff are compelled to resort to epistemological triage, assessing vulnerability on the basis of broad demographic characteristics, and likely missing many (arguably especially men) subjected to sexualised torture.

This is less a case of protection than carceral humanitarianism, which "turns refugees into criminals and charity cases simultaneously, which, in turn, becomes the troubling justification for ‘rescuing’ them in order to lock them up or lock them in.” https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/carceral-humanitarianism">https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-divi...

The outsourcing of protection allows EU officials to claim they are responsive to WPS without having to implement it proactively. The ‘gender perspective’ is thus limited to a compromised, partial form of rescue, with detention and abuse accepted for the majority of migrants.

More to say, but this thread is already too long. If you can’t access the article and want to read more, drop me a message here or through my work email.

Open access would have been nice, but I didn’t have £3,000 to spare.

Open access would have been nice, but I didn’t have £3,000 to spare.

Final shout-out and gratitude to @MauriceStierl, @Tsanga10, @Myriamincheek, and to the interviewees who gave so generously of their time and knowledge.

Give to https://sea-watch.org/en/ ">https://sea-watch.org/en/"...

Give to https://sea-watch.org/en/ ">https://sea-watch.org/en/"...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter