This is what I& #39;m going to call entry #31 in project #EuropeanBios but I just went and checked and discovered there were two #10s and also two #16s? Whatever, there& #39;s no edit button, we& #39;re stuck with this. Entry number 31 or possibly 33 is Marco Polo and his life with Kublai Khan.

Marco, born in Venice in 1254, turns out to have been an EXCELLENT choice of subject because he& #39;s one of those people whose name you& #39;ve heard a thousand times but I for one had only the very vaguest idea of what he was famous for, so there are many surprises.

(As always, if you want the bio or any of the others I& #39;ve covered in #EuropeanBios, they& #39;re all covered in exhaustive detail in a spreadsheet, because how else could I keep track of all this? #gid=0">https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1iCVT3U6nSpHSD1fHDGOncEKoi_SS-ZJhQc7r0PAEqZ4/edit #gid=0">https://docs.google.com/spreadshe... )

I& #39;ll be honest, if you& #39;d asked me what Marco was famous for I& #39;d have said "he visited China and... brought stuff back? Also he crossed mountains using elephants?" The first part is semi-correct and the latter is confusing him with Hannibal: https://twitter.com/seldo/status/1239045363933175808">https://twitter.com/seldo/sta...

What he actually did is visit the Mongols, who at the time had conquered most of Asia including China. And he didn& #39;t so much visit as live in the Mongol empire working semi-willingly for Kublai Khan for more than 15 years, seeing most of Asia as part of his various jobs.

So Marco& #39;s not super-interesting in himself but it does give us an excuse to revisit the Mongols, who have changed dramatically since we last met them under Genghis Khan, real name Temüjin, a few threads back: https://twitter.com/seldo/status/1295139244831195137">https://twitter.com/seldo/sta...

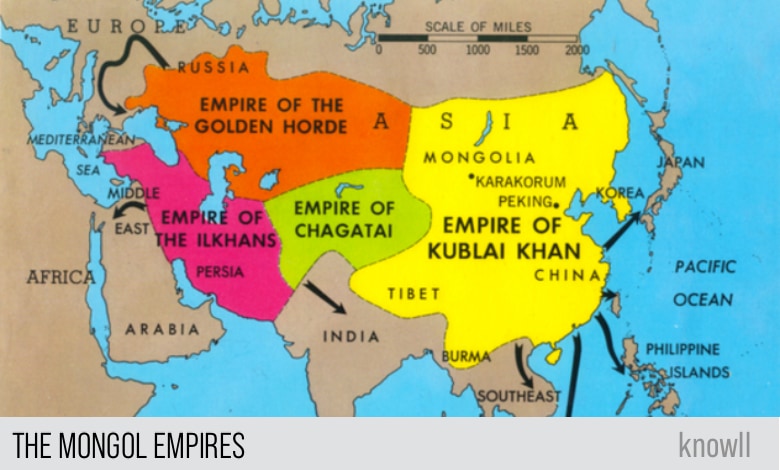

Temüjin conquered the whole fucking world and left it to his kids. The split it up after his death but remained nominally a single empire under Kublai Khan, Temüjin& #39;s grandson, though his power outside of his immediate territory was strictly limited.

Under Temüjin the Mongols were a giant, permanently mobile conquering army, illiterate and incredibly tough. They conquered China, but China& #39;s old and immensely powerful culture proved stronger than its invaders, and the Mongols became sinicized, adopting much Chinese culture.

It was this new, sedentary, highly literate, bureaucratized, strongly Chinese-flavored Mongol empire that Marco visited. So it& #39;s true to say "Marco Polo visited China" physically, but China was not independent, it was the Chinese portion of the greater Mongol empire.

Marco was also not the first to visit China, not by a long shot. Trade between Europe and the Mongol empire was brisk. He wasn& #39;t even the first in his family to make the trip: Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, Marco& #39;s father and uncle respectively, visited while Marco was still a baby.

Nic and Maffeo got all the way to Kublai Khan& #39;s court, where they were made ambassadors to the Pope, and also tasked with obtaining some holy oil from Jerusalem (the Mongols enjoyed full religious freedom including Christianity, so Kublai was familiar with it).

By the time they returned to Europe to complete this task, they& #39;d been gone a decade, so toddler Marco was 15 years old when his father and uncle returned. His mother had died soon after Niccolò left, so Marco had been living with an aunt and uncle.

After a couple of years waiting for a Pope to be appointed (he& #39;d died and there was a big fight over succession), they did their ambassador thing, got the oil (Jerusalem did a brisk trade in it), and set out to get back to Kublai& #39;s court, this time with 15 year old Marco in tow.

I dunno about you, but there are some surprises here for me. His dad had already made the trip! He was only 15 when he did it! Going to Kublai& #39;s court wasn& #39;t even his idea! He didn& #39;t have any reason to be there! This is all quite different from how I& #39;d imagined Marco& #39;s journey.

So the question is: visiting Kublai Khan& #39;s court was rare but not unheard of, all the goods Marco eventually brought back were well-known commodities already. So why is Marco Polo famous? What did he do that made him stand out from the others who made the trip?

The answer is: he wrote it down. Or more accurately, a man called Rustichello da Pisa wrote it down for him, and in fact took quite a lot of license with his stories, crediting Marco with heroic roles in battles he wasn& #39;t present for, and putting him in places he never went.

Part of this is because Marco himself was something of a fabulist, embellishing and exaggerating his own tales. Part is that Rusticello tried to make things more exciting. But a big part is that the two of them decided to write the thing in French, which neither of them spoke.

They decided to write in French (in fact a French-Venetian mish-mash) because that was the fashion at the time. But they weren& #39;t very good at the language, so they kept skipping back and forth between past and present tense, first and third person, even within a single sentence.

Publishing was also extremely rudimentary at the time, so many different versions of Marco& #39;s book exist, all of different lengths with different bits of material included or omitted, and with the order of chapters liberally shuffled. The result is a confusing mess.

Marco& #39;s accounts of his travels are often criticized for being partly or perhaps wholly made up, and the disastrous state of the book is why. In his broken French it& #39;s hard to tell whether he *intended* to say he was present, or that other people were, or when something happened.

But Marco& #39;s stories survived because he kept a diary and was a fantastic story teller, engaging and convincing. When he got back from his travels he got caught up in a war between Venice and Genoa, was captured, and spent five years in captivity, where he met Rustichello.

As for his travels themselves, this thread is already too long. He wrote about travels through the middle east, central Asia, China itself, Japan, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and even Zanzibar (it& #39;s disputed if he actually went there) and Russia (he definitely didn& #39;t go).

He accompanied his father and uncle to Kublai Khan& #39;s court, where the Khan was overjoyed to have actually received communication from the Pope and the semi-mythical holy oil he& #39;d asked for. He showered the Polos with riches and honors and asked them to do more things for him.

Kublai gave Marco and the other Polos a paiza, an ornate, inscribed physical object recognized across the empire as a mark of imperial favor. Anywhere you went in the empire, a paiza meant you& #39;d get aid, shelter, horses and other resources from the local rulers.

So as an ambassador of Kublai, Polo visited every part of the Mongol kingdom. He spent well over half his life doing it, and was profoundly changed by the experience. He became Mongolian in thought, habits, dress and even his attitudes to religion.

But eventually being Kublai& #39;s most prized ambassador became a problem, because having the exotic, well-traveled Polos around became a point of status and honor that the ageing Khan needed to maintain his position. He wouldn& #39;t let them leave. But Kublai was getting old and sick.

If their generous benefactor were to die, his successor would not favor them, and certainly not give them the kind of powerful promises and protections they needed to be able to cross the vast territory of the empire back to Europe in safety. How to save face but also get home?

The result was a fudge. Kublai assigned them a new task: accompany a princess to be married in a khanate in the middle east. Conveniently, that khanate was half-way back to their home in Europe. Even more conveniently, no provision was made for their return trip. They were free.

This trip got them back to Europe with the full authority of the Khan behind them to grant them safety and transport, and just in time -- he died while they were en route, and news of his death caught up with them before they were fully home, so they had to pay hefty bribes.

The princess they accompanied was not so lucky. Her husband-to-be had also died while they were on the way. The new ruler was not interested in being married to a "gift" princess from the now-dead Khan, so the princess, surplus to requirements, was executed soon after arrival.

Then Marco and his family got back to Venice and discovered that they had been assumed dead for years, and their appearance was so changed by 15 years of absence that even their own family were not sure whether they were the real Polos or exotic impostors.

But family connections and also the huge numbers of valuable gems and other commodities they& #39;d brought back from empire eventually won Venice over and they were celebrated. Only 30, Marco lived another half of his life again back in Venice, dying aged 70 in 1324.

In terms of legacy, Marco is famous primarily for being well-traveled and an excellent story teller. A great number of things have been attributed to him that aren& #39;t true, a few of which he claimed but the majority of which accumulated long after he died.

In particular it& #39;s claimed he brought various things back for the first time -- chess, checkers, pasta, silk, maps -- but as I mentioned trade between Europe and the Mongols was booming and all of that stuff had been around for years, sometimes centuries before Marco left.

Marco& #39;s messy book and many inaccuracies have even had some people claim he never went to China, he just listened to trading stories and put it all together. But he had in his possession the golden paiza from Kublai Khan himself, so we can be sure he really went.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter