Livetweet thread for the game "Moon: Remix RPG Adventure" #moon_rpg (which isn& #39;t live at all because I needed to get to the end to decide whether or not to make a thread for it. What was my decision? There& #39;s no way to know). [1/53]

Before I promote this game, you have to bear this content in mind: it has a racist caricature NPC design, a anti-semitic caricature NPC design, a stereotyped "angry feminist" NPC, and an eyerolling kiss-and-make-up-after-domestic-violence scene. ("That is love"? Sure, whatever.)

Also, there& #39;s a homeless character who, while treated with respect by the NPCs (and crucially, the translator), still has his impoverished existence entirely unexplained and taken for granted (and seems to exist just for a zany Prince-and-Pauper style friendship with the King.)

And another thing: there are several audio-coded puzzles in this game, as well as several colour-coded puzzles, both kinds of which are MANDATORY to finish the game. These are unchanged from their original 1997 version and have NO disability affordances.

These caveats are extremely good reasons to not play the game. Another good reason is that at times it locks mandatory progress behind VERY missable tasks (such as not checking an innocuous object in the front of a certain room) with almost zero textual nudges to it.

And in addition to that, the in-game hint system can be highly misleading, often giving hints for puzzles in stages of the game or NPC relationships that simply aren& #39;t accessible yet, or otherwise being so vague that pinpointing a time or location for the goal is very difficult.

Regarding track 26:

In the game of Moon, you can purchase an in-game CD containing the song "Father, Give Me God& #39;s Power", credited to "Inauini Riverside People". I decided to do a bit of research into the meaning of this rather vague attribution. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiVygvRvX7c">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

In the game of Moon, you can purchase an in-game CD containing the song "Father, Give Me God& #39;s Power", credited to "Inauini Riverside People". I decided to do a bit of research into the meaning of this rather vague attribution. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiVygvRvX7c">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

In the OST "The Sketches of Moondays", the song is described as a fusion of Deni shamanic songs and Christian resurrection hymns. It& #39;s also accompanied with a painfully ignorant illustration, deploying typical anti-black design aspects to depict a Brazilian indigenous subject.

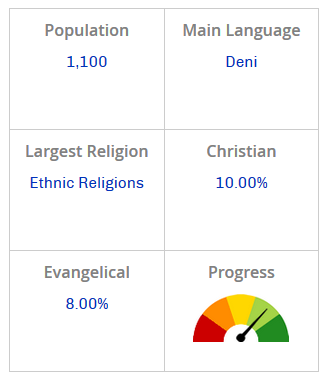

From what I can tell, the current accepted name for these people is Deni. They do not have a Wikipedia page - most of my information is from https://pib.socioambiental.org/en/Povo:Deni .">https://pib.socioambiental.org/en/Povo:D... The Inauini River does have a Wikipedia page, which is a stub with four sentences.

The majority of Western scholarly work on the Deni is by the Christian missionaries Gordon and Lois Koop, who arrived in 1972. I wonder if such missionaries are the only recorders of Deni cultural audio, and whether non-Christian recordings exist, even for scholarly purposes.

According to the US Evangelical conversion org Joshua Project https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/11535/BR">https://joshuaproject.net/people_gr... """only""" 10% of Deni have been converted to Christianity, though considering their "Progress" meter is at *squints* "pale green", I suppose that is increasing as we speak.

This track& #39;s inclusion in Moon is probably just naïve 90s "multiculturalism" that& #39;s deeply ignorant of colonial context, but I do think this being a Christianised indigenous song rather blatantly invalidates the in-game claim that the song is "a direct message from the Earth".

Regarding my history with Moon:

I first learned of Moon in the early 00& #39;s. At that time, the only way to experience the game in English was to read this ONE (1) GameFAQs review in 2002 (by @wyrdwad_tom) https://web.archive.org/web/20021024012207/http://www.gamefaqs.com/console/psx/review/R38576.html">https://web.archive.org/web/20021... That& #39;s it. Just this one text file.

I first learned of Moon in the early 00& #39;s. At that time, the only way to experience the game in English was to read this ONE (1) GameFAQs review in 2002 (by @wyrdwad_tom) https://web.archive.org/web/20021024012207/http://www.gamefaqs.com/console/psx/review/R38576.html">https://web.archive.org/web/20021... That& #39;s it. Just this one text file.

Now that the game is translated, do not actually read the linked review before playing: it consists of a thorough description of the game& #39;s opening.

At the time, though, the game it described seemed so captivating, so uniquely human, that I ached with loss for it.

At the time, though, the game it described seemed so captivating, so uniquely human, that I ached with loss for it.

What really struck with me was how it subverted Dragon Quest 1 in particular – the rainbow arch corresponding to the Rainbow Bridge, for instance. The idea of a published game directly deconstructing another (differently from stuff like Parodius) was then fresh and unknown to me.

The fact of this game being knowable only through this one report, this tiny sliver of light, added an additional note of tragedy - such a beautiful-sounding game reduced only to a legend, unknown to the English world.

So, that& #39;s the baggage I brought into this game.

So, that& #39;s the baggage I brought into this game.

The main thing I was NOT prepared for was the art direction of Moon, which blends now-modest prerendered CG with clay assets and photographed assets, a blend that lines up eerily with indie RPG-ish games of the 10s, including Mason Lindroth, Jack King-Spooner and thecatamites.

The use of claymation for various NPCs in the game is a timeless stroke of ingenuity, but what really bowled me over is the late reveal that all NPCs rendered in claymation has some special quality uniting them all, revealing a purpose for it hidden in plain sight.

Suddenly taking this seemingly ornamental aspect of the game and transforming it into a meaningful signifier is one of my favourite little narrative tricks. What& #39;s more, Moon then leverages that revealed meaning to show something beautiful even later in the game.

That said, though, the most meaningful aspect of this is how sharply Moon visually diverges from the "fake" JRPG, to the point where it scarcely resembles a videogame world - which results in making The Hero& #39;s actions especially shocking and unfamiliar when he does appear.

Regarding Moon as "anti-RPG":

People like to frame this and Undertale as being primarily "anti-violence" stories, and while that& #39;s very useful for marketing, I absolutely don& #39;t think that& #39;s the single "point" of these games, or even what their endings are trying to tell you.

People like to frame this and Undertale as being primarily "anti-violence" stories, and while that& #39;s very useful for marketing, I absolutely don& #39;t think that& #39;s the single "point" of these games, or even what their endings are trying to tell you.

Moon isn& #39;t meant to be a 12-hour-long "the player is bad" twist, or a 12-hour-long parody of 80s JRPGs.

It is, simply put, a fairytale about a world (a game world) that is trapped in a prewritten fate (the game& #39;s story) and wishes dearly that it could become something else.

It is, simply put, a fairytale about a world (a game world) that is trapped in a prewritten fate (the game& #39;s story) and wishes dearly that it could become something else.

The character of The Hero isn& #39;t really meant to just be the "Violent Minmax Gamer" - indeed, The Hero has his own in-universe hidden backstory that entirely explains why he acts like he does - but embodies the inexorable, tragic fate the game world can& #39;t escape from.

[Special https://rot13.com/ ">https://rot13.com/">... sentence] "Fheryl, gubhtu, Gur Ureb vf fbyryl gur snhyg bs Gur Zvavfgre?" Ab. Jul vf Gur Ureb& #39;f perngvba ol Gur Zvavfgre& #39;f unaq vafpevorq ba n Ehzebz? Orpnhfr rira gung, rira Gur Zvavfgre& #39;f znpuvangvbaf, vf rapbqrq va gur tnzr, va sngr.

Moon& #39;s use of game cartridge ROMs to symbolise fate - one of the few objects in Moon World that directly allude to it being a videogame world - is honestly a brilliant move, succinctly explaining how Moon World& #39;s fate is prewritten, for what purpose, and why it can& #39;t be defied.

Undertale, similarly, isn& #39;t really about the player becoming a pacifist, but about teaching the world to become pacifist - to heal a hurt and imprisoned world, and bring peace to increasingly hurt and imprisoned bosses, culminating in that little underworld& #39;s analogue to Satan.

Undertale does have a character representing the Violent Minmax Gamer, in no uncertain terms, but they only appear if you voluntarily act as one, if you teach that character those values, which the narrative regards as foreign to it, brought in from the real world to its own.

This is a big point where Undertale and Moon diverge: the "fake" Moon JRPG Hero cannot act or perceive reality in any other way. His violence is encoded in the story, and everything in the world – including himself – cannot break free of it. Unlike Undertale, it& #39;s not a choice.

Undertale is about choices, about discovering them in yourself and revealing them to others. Moon is about struggling to change the unchangeable and escape the inescapable, to eke out moments of peace inside a literal machine of violence that can& #39;t be stopped.

Regarding "Open The Door":

Something I admire about Moon is how at the 20% mark, it vividly introduces this mystery phrase that has no mapping to anything in the "fake" Moon JRPG, suggesting, as the novelty of the RPG parody wears off, that there is Another Solution.

Something I admire about Moon is how at the 20% mark, it vividly introduces this mystery phrase that has no mapping to anything in the "fake" Moon JRPG, suggesting, as the novelty of the RPG parody wears off, that there is Another Solution.

This phrase - "Open The Door" – serves the same purpose as "the Green Sun" in Homestuck or "the Wind Fish" in Link& #39;s Awakening - an underexplained term that evokes an image but not any concrete meaning, which efficiently charges the subsequent hours with an air of anticipation.

What I really like about all of these is how much confidence they have in the concept, that a simple phrase can be compelling on its own simply by letting it sit as an enticing non-answer to the player& #39;s ongoing question of "how do I escape this fate"?

I think about how one of my least favourite prequels, Ocarina Of Time, throws out a cluster of concepts – "Sacred Realm", "Seven Sages" - so ornately encrusted with breathless prose that they wash away all curiousity, and how insecure and eager-to-please it all comes across.

More importantly, the later stages of Moon build the anticipation of "Open The Door" by amplifying the references to it – more and more brief mentions, winding all the way up to a huge song-and-dance number about it - while still keeping its full meaning unstated until the end.

On Moon World:

Playing Moon made me think about the "zany cartoon fantasy world", a setting that in the 90s was still crystalising with Link& #39;s Awakening and such, but now is so common as to essentially be its own dominant genre in itself, across cartoons, comics and games.

Playing Moon made me think about the "zany cartoon fantasy world", a setting that in the 90s was still crystalising with Link& #39;s Awakening and such, but now is so common as to essentially be its own dominant genre in itself, across cartoons, comics and games.

The "zany cartoon fantasy world" is a world whose trappings are high fantasy (swords, magic, castles, kings) but which is jokey and nondescript enough that anything from any setting can suddenly appear, like record stores, Goombas, game shows, post-apoc ruins, et cetera.

At the time, this setting definitely came across as fresh and subversive, and in this game it represents "reality" compared to the 16-bit world of the "fake" JRPG. But now, in this decade, I feel like it& #39;s aged into simply another, different, kind of escapist fantasy world.

When witnessing both versions of, say, the Perogon scene, both of them seem, outside of the greater context of the narrative, to be two different stylisations of those events, rather that one obviously superceding the other with its novelty and strangeness.

On fish and money:

If I were making Moon, a game that emphasised quietly examining the world instead of exploiting it for resources, I would probably not include any kind of fishing, let alone the ability to sell fish for profit, or having it be a competitive sport.

If I were making Moon, a game that emphasised quietly examining the world instead of exploiting it for resources, I would probably not include any kind of fishing, let alone the ability to sell fish for profit, or having it be a competitive sport.

I understand that fishing often appears in games as a tranquil counterpart to the "main quest"& #39;s violence, yet in practice these minigames almost always devolve into resource exploitation, either by intersecting it with the game& #39;s economy, or attaching other rewards to it.

It isn& #39;t surprising that Moon has a profitable self-serving fishing minigame, but I do find it dissonant with the game& #39;s goals. It& #39;d be more unified if selling fish and the competition were removed, leaving fishing& #39;s "quest purpose" as just a source of submerged non-fish items.

Speaking of economics, I have to say that Moon& #39;s in-game economy is actually pretty poorly balanced - it& #39;s rather easy to run out of money, and the game& #39;s few "regrowing" items sell for very little. The fastest way to gain money is to savescum the gambling minigame& #39;s highest bet.

This game would definitely be better if the player-character had a sizable daily allowance or income that turned essential money into a non-issue, reducing it to just another number relevant only to The Hero, just as only levels are relevant to him.

On the fourth wall:

As with Undertale, no one in Moon World (except the player-character, who doesn& #39;t let on) is directly aware that their world is a videogame& #39;s world. The most that is stated by the characters are references to The Hero& #39;s levels and stat points.

As with Undertale, no one in Moon World (except the player-character, who doesn& #39;t let on) is directly aware that their world is a videogame& #39;s world. The most that is stated by the characters are references to The Hero& #39;s levels and stat points.

The true meaning of the ROMs is unknown to Moon World& #39;s inhabitants, just as the true meaning of "SAVING" is unknown to Flowey in Undertale, who uses that term entirely as an analogy, and only really understands it as "returning from death".

This is fascinating to me because it shows a carefulness, by both games, to not focus too deeply on parody or genre-deconstruction, and instead keep attention on the world on its own terms, as a place in itself.

It also means that both games don& #39;t freely refer to game concepts out-of-universe, instead picking and choosing a few and wrapping them in an in-universe meaning. For Moon, the ROMs for the game& #39;s coded story. For Undertale, the concept of "determination" for player autonomy.

This means both games can precisely express what /about/ the videogame form they are interested in: for Undertale, it& #39;s about the ability to choose and to find another way. For Moon, it& #39;s about how an ostensibly interactive game can still have an immutable narrative.

On Moon& #39;s ending:

Feel free to close the thread now if you don& #39;t want even vague details about this.

Feel free to close the thread now if you don& #39;t want even vague details about this.

My review of Moon& #39;s ending is that it is extremely good. HOWEVER, it requires you to understand exactly what the portrayed events are trying to tell you, or else make a leap of intuition, and if you do not, it is VERY likely to backfire on you and give you a bad experience.

I feel like this ending sits on a cliff-edge. I was lucky - I landed on the cliff, but many others may not. It is, again, very good, but SOOO dangerous. I would call it "risky" if the rest of the game& #39;s poor puzzle guidance didn& #39;t make me doubt the makers& #39; awareness of the risk.

The ending really convinced me that this game has a very focused narrative point beneath its outward layers of parody and zany dialogue, that all of it was building up to a coherent whole, and it left me deeply elated.

Start of thread: https://twitter.com/webbedspace/status/1302613307795234816">https://twitter.com/webbedspa...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![End of thread. [53/53] End of thread. [53/53]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EhPQ0OkUcAIjlS6.jpg)