During the past decade, many of you were subject to see our Jerusalem supermarkets paper in seminars and workshops. Possibly more than once.

It is now accepted at the AEJ:Policy, prompting this THREAD about inequality, IO and econometrics -->

https://scholars.huji.ac.il/sites/default/files/aloneizenberg/files/ely_july2020.pdf">https://scholars.huji.ac.il/sites/def...

It is now accepted at the AEJ:Policy, prompting this THREAD about inequality, IO and econometrics -->

https://scholars.huji.ac.il/sites/default/files/aloneizenberg/files/ely_july2020.pdf">https://scholars.huji.ac.il/sites/def...

There is a large Urban economics literature asking whether "the poor pay more?"

The question is natural: in a large metropolitan area, non-affluent consumers live in different neighborhoods, and have access to different shopping opportunities than affluent consumers. -->

The question is natural: in a large metropolitan area, non-affluent consumers live in different neighborhoods, and have access to different shopping opportunities than affluent consumers. -->

The question is also important: if different socioeconomic groups face different price indices, measuring inequality may be quite tricky. The message from the literature, however, is mixed: some found that the poor pay higher retail prices, others found that they pay less. -->

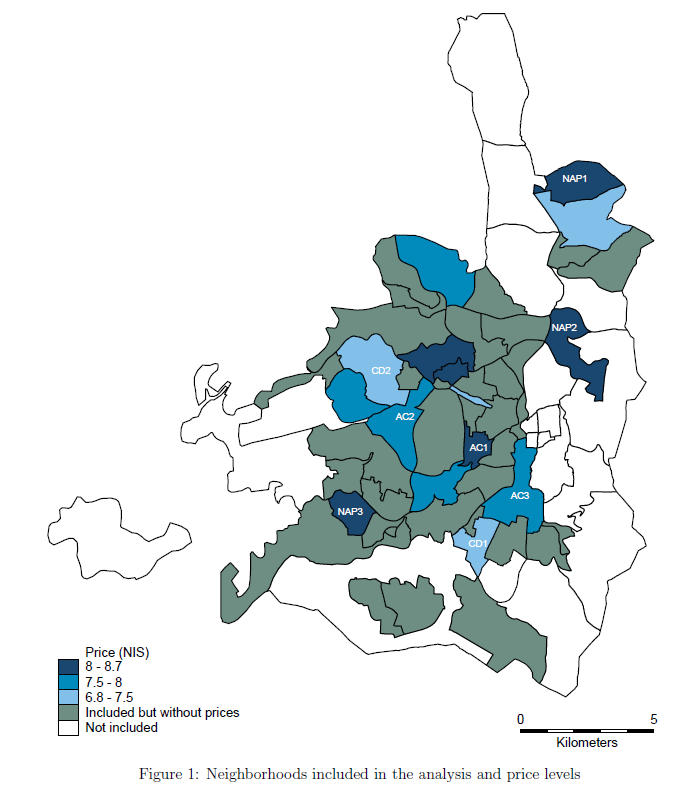

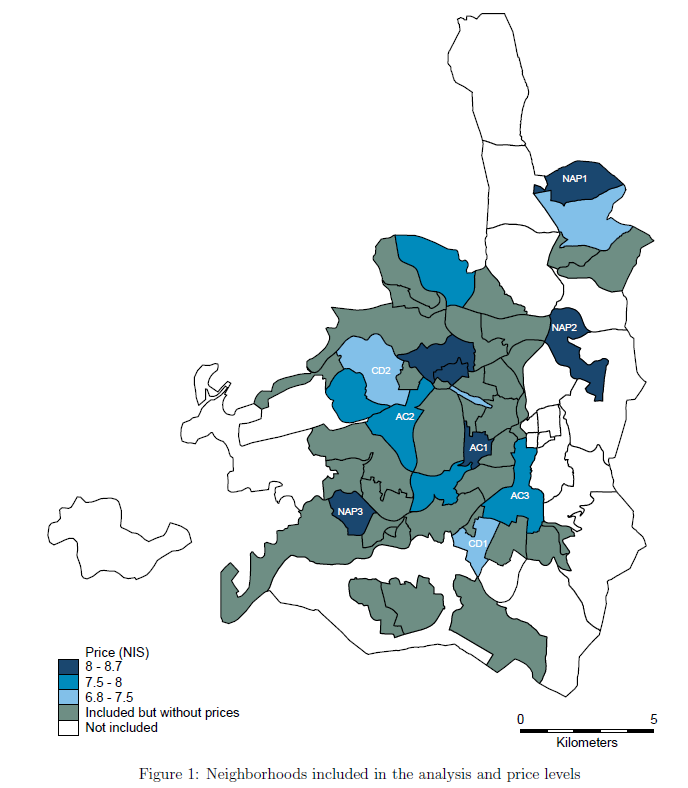

We came to think about this in the context of grocery price dispersion across Jerusalem& #39;s neighborhoods. Data from the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics confirmed what we already knew: prices for a basic basket of goods were quite different across neighborhoods. -->

Prices were very high in the Affluent, Central neighborhood labeled as AC1. But they were also very high in three Non-affluent, peripheral neighborhoods labeled NAP1-NAP3. They were somewhat lower in the affluent & central neighborhoods AC1-AC2.

What might explain this? -->

What might explain this? -->

We hypothesized that socioeconomic standing interacts with spatial frictions in important ways. AC1-AC2 prices were disciplined by the close proximity of Hard Discount grocers in the commercial districts (CD1-CD2). This chilling effect was naturally weaker in NAP n& #39;hoods. ->

This led us to consider some important aspects of cross-neighborhood price differentials. First, much of the literature simply compared prices charged across affluent vs. non-affluent n& #39;hoods. But in fact, residents of each neighborhood face a vector of prices since they can -->

shop outside their home neighborhood. So getting data on where people actually shop is important. Moreover, equilibrium prices are determined by demand & supply primitives: socioeconomic standing, spatial frictions, and marginal cost differentials. -->

To capture these aspects, we obtained aggregate (n& #39;hood-level) consumer expenditure flows from a credit card company, and estimated a structural model where residents of each n& #39;hood choose where to shop, and retailers across the city set prices a-la Nash-Bertrand. -->

The raw credit card data conformed with our hypothesis: despite being charged very high prices in their home neighborhood, NAP residents displayed a larger-than-average tendency to shop in it. This is consistent with lack of good, accessible outside options. -->

Our structural estimates revealed strong spatial frictions: "pushing" a destination n& #39;hood 1 km further away reduced your probability of shopping there by 35%. NAP retailers faced less elastic demand and charged higher margins, but also faced higher marginal costs. -->

In light of this, you may expect that alleviating spatial frictions should lower prices at the NAP n& #39;hoods by exerting stronger competitive pressure.

But our counterfactuals suggested that NAP prices barely change, or even *increase*. Was this a coding error? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😱" title="Vor Angst schreiendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Vor Angst schreiendes Gesicht">->

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😱" title="Vor Angst schreiendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Vor Angst schreiendes Gesicht">->

But our counterfactuals suggested that NAP prices barely change, or even *increase*. Was this a coding error?

No. Spatial frictions have interesting distributional effects even within n& #39;hoods: not all residents of NAP n& #39;hoods are the same.

Imagine they are of two types: "mobile" and "non-mobile", differing in the cost of travel or in the opportunity cost of time. -->

Imagine they are of two types: "mobile" and "non-mobile", differing in the cost of travel or in the opportunity cost of time. -->

When the spatial friction is alleviated (think of infrastructure work that reduces congestion and makes it easier to move around town), the mobile residents of NAP n& #39;hoods welcome the opportunity to abandon their local grocer in favor of hard-discount grocers elsewhere. -->

The local grocer now sells mostly to the "non-mobile" types. So she now faces *less* elastic demand than before, and may actually raise prices rather than lower them, despite facing stronger competition from the hard-discounters operating elsewhere in the city. -->

So, lower spatial frictions and stronger competition benefit some, but not all residents of the non-affluent, peripheral neighborhoods. While the cost of grocery shopping is reduced for those able and willing to shop outside the home n& #39;hood, eq& #39;m prices barely change. -->

So the 85-yr old NAP resident, who does not drive and shops at the local grocer, gains nothing from increased spatial competition. This surprised us, but the mechanism is familiar to economists as the "generic drug paradox": drug prices rising when generic competition enters. ->

The main insight is that to fully appreciate the causes and consequences of cross-neighborhood retail price differentials, we need to go beyond price data. Adding data on where people actually shop, and modeling the eq& #39;m effects can be helpful. -->

On the econometrics front, this project produced quite a few challenges. First, how do you estimate a demand system where each n& #39;hood is both a "market" and a "product"? Well, you get something similar to a gravity model, but with explicit modeling of consumer utility. ->

Second, how should we measure consumer flows across n& #39;hoods? Supermarket papers typically use scanner data, but we found that aggregate credit-card expenditure flows were actually quite useful in adequately capturing shopping probabilities in a large matrix. -->

Third, not all Jerusalemites use credit cards (though most do). We worked out a way of combining the rich data structure with identifying assumptions to tackle sample selection within the nested-logit framework. -->

Finally (is anybody still here?  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😃" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund">), a word about the process. This project took almost a decade. The accepted version is 40% shorter than the WP versions, the rest going into a monumental online appendix to which we became quite emotionally attached. -->

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😃" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund">), a word about the process. This project took almost a decade. The accepted version is 40% shorter than the WP versions, the rest going into a monumental online appendix to which we became quite emotionally attached. -->

We are very much grateful to all readers, commentators and colleagues who made this paper better. This is the nice part: people do care about the details of what you do, and you learn a lot as you go along. You just need to keep going...THE END

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter