VIDEO THREAD:

#Sudan’s government celebrates the signing of a peace agreement in #Juba, but key questions remain:

•How comprehensive is the deal?

•Does it address the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts?

•Are all rebel groups satisfied with the deal?

#SudanUprising

#Sudan’s government celebrates the signing of a peace agreement in #Juba, but key questions remain:

•How comprehensive is the deal?

•Does it address the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts?

•Are all rebel groups satisfied with the deal?

#SudanUprising

CONTEXT:

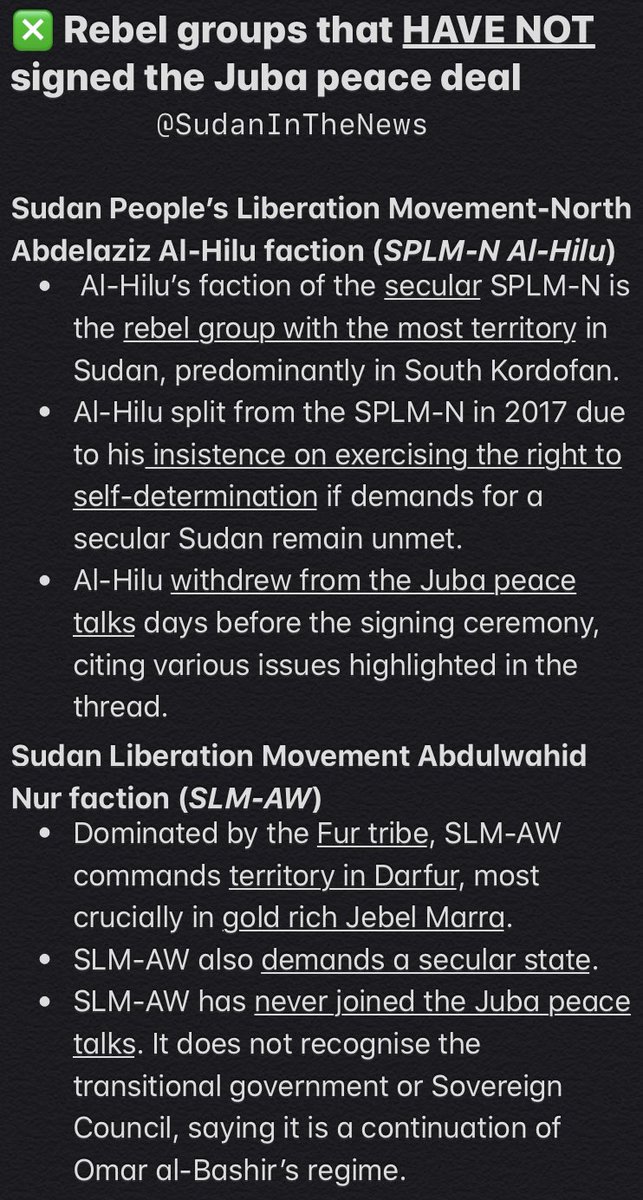

For a brief summary of Sudan’s key rebel groups, their ideological position, and their participation with regards to the peace talks, see below:

For a brief summary of Sudan’s key rebel groups, their ideological position, and their participation with regards to the peace talks, see below:

From here on in, the clips used in this thread are from the @AtlanticCouncil’s ‘Prospects for peace in Sudan’ discussion moderated by @_hudsonc.

To view the full discussion on Youtube: https://youtu.be/kVj-_LUwy7s ">https://youtu.be/kVj-_LUwy...

To view the full discussion on Youtube: https://youtu.be/kVj-_LUwy7s ">https://youtu.be/kVj-_LUwy...

The discussion featured two rebel leaders:

•Dr. Gibril Ibrahim of the Justice and Equality Movement.

•Abdelaziz al-Hilu, a factional leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North.

Ibrahim and al-Hilu disagreed on five key areas:

•Dr. Gibril Ibrahim of the Justice and Equality Movement.

•Abdelaziz al-Hilu, a factional leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North.

Ibrahim and al-Hilu disagreed on five key areas:

1. The dominance of the peace talks:

I. On one hand, Ibrahim said the military did not dominate the peace talks, and that the civilian wing of the government was actively involved in the process.

I. On one hand, Ibrahim said the military did not dominate the peace talks, and that the civilian wing of the government was actively involved in the process.

II. However, al-Hilu blamed his withdrawal from the peace talks on the chairman of the government delegation, Rapid Support Forces commander Himedti.

Al-Hilu said: “[Himedti’s forces] are displacing the displaced all over the country.”

Al-Hilu said: “[Himedti’s forces] are displacing the displaced all over the country.”

2. Disagreements on the progress of the talks:

I. Al-Hilu said the talks produced “piecemeal solutions” that fail to address the root causes of conflicts plaguing Sudan since independence, namely: the marginalisation of the peripheral regions by Khartoum.

I. Al-Hilu said the talks produced “piecemeal solutions” that fail to address the root causes of conflicts plaguing Sudan since independence, namely: the marginalisation of the peripheral regions by Khartoum.

II. By contrast, Ibrahim said the peace talks heralded “historic breakthroughs” in key areas including:

•Land ownership.

•Regional autonomy and devolution of powers.

•The redistribution of wealth from natural resources.

•Land ownership.

•Regional autonomy and devolution of powers.

•The redistribution of wealth from natural resources.

III. Ibrahim said the peace talks were participatory and inclusive of women, but attributes the absence of refugees and the internally displaced to “administrative and logistical issues”.

He claimed that their representatives endorse the peace process, and will implement it.

He claimed that their representatives endorse the peace process, and will implement it.

3. Differences in sentiment towards the government in Khartoum:

I. Ibrahim said the new government is different from al-Bashir’s regime, presenting a “window of opportunity” for change. He added that the talks are addressing the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts.

I. Ibrahim said the new government is different from al-Bashir’s regime, presenting a “window of opportunity” for change. He added that the talks are addressing the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts.

II. However, al-Hilu argues that the transitional government’s “insistence” on Islamic law fits into a wider historical pattern of Sudanese state failure caused by the inability of ruling elites to manage Sudan’s religious and ethnic diversity.

4. Ideology:

I. Ibrahim did not expand on JEM’s ideology, but al-Hilu re-iterated his calls for a secular constitution.

Al-Hilu argues that secularism will “lay the foundations for a multicultural state” that can guarantee peace and “loosen the grip” of the Islamists.

I. Ibrahim did not expand on JEM’s ideology, but al-Hilu re-iterated his calls for a secular constitution.

Al-Hilu argues that secularism will “lay the foundations for a multicultural state” that can guarantee peace and “loosen the grip” of the Islamists.

II. Al-Hilu added that secularism will “neutralise” the state, thereby helping to build a common national identity that will achieve peace and justice.

III. Al-Hilu warned that if the secularism issue is not addressed, different ethnicities will exercise the right to self-determination.

He blamed Sudan’s history of conflict on successive governments being unable to expand their public legitimacy to the peripheral regions.

He blamed Sudan’s history of conflict on successive governments being unable to expand their public legitimacy to the peripheral regions.

IV. Sudanese political analyst Elshafie Khidir called for the government to “carefully” address the issues identified by al-Hilu concerning the role of religion in the Sudanese state.

5. Disagreements around the proposed constitutional conference:

Ibrahim said that the Juba peace agreement will be followed by:

•A constitutional conference and new constitution.

•Democratically elected government that will facilitate change.

Ibrahim said that the Juba peace agreement will be followed by:

•A constitutional conference and new constitution.

•Democratically elected government that will facilitate change.

II. By contrast, al-Hilu‘s position was that the Juba peace talks should have formed the basis for a secular constitution - a matter that “must not be deferred until after the elections”.

III. Al-Hilu referenced Sudan’s post-independence history to argue that constitutional conferences are “tactically” employed by political elites to “avoid” discussing the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts.

IV. Thus, al-Hilu concludes that Sudan’s current peace process bears similarities to those initiated after the 1964 and 1985 civil uprisings: whereby “[civilian and military] elites always avoid to discuss the root causes and the real issues” behind Sudan’s history of conflict.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter