Edgar #HopeSimpson’s description of the seasonal nature of influenza will be familiar to followers of @FatEmperor @boriquagato @EthicalSkeptic. Seasonality, however, was but one of 21 questions he raised about the received wisdom concerning the transmission of flu. 1/-

In 1977, Fred Davenport, of the Dept of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan wrote, "Epidemiological hypotheses must provide satisfactory explanations for all the known findings – not just for a convenient subset of them." Hope-Simpson called this Davenport’s dictum. 2/-

Hope-Simpson said our current concept of epidemic influenza was like a milk bucket; even one hole and all the milk is lost: “So many holes exist in the current concept of direct measles-like spread of influenza that the hypothesis more resembles a colander than a bucket.” 3/-

Hope-Simpson had suffered a bout of Spanish Flu as a schoolboy in 1918. He became a general practitioner in 1932, also then becoming pathologist, and epidemiologist, and built an epidemiological research unit at his surgery. 4/-

As a GP, Hope-Simpson felt it best to focus his epidemiological research on the common illnesses he saw regularly in his practice: measles, chickenpox, mumps, influenza. 5/-

Hope-Simpson had the insight that chickenpox and shingles might be caused by the same virus, which could lie dormant in the carrier for years. He identified a means to demonstrate this and, by leading a team to a remote island to track down every case there, he succeeded. 6/-

During a flu epidemic in 1932, Hope-Simpson had noted that some of the earliest cases were located at remote farms and cottages – places which had with little communication with the outside world. 7/-

In 1957 a new strain of Influenza A (Asian Flu) reached the UK. Hope-Simpson tracked its progress through the patients at his surgery. It had erupted, attacking 8% in 3 weeks and looked set to attack a huge proportion. 8/-

Yet Hope-Simpson was surprised to find that the Asian flu had already peaked, eventually attacking only 15% in six weeks. A new virus had gained a foothold in a non-immune population but then, mysteriously, petered out. 9/-

It would later be shown that some people over 70 were immune – this ‘new’ virus must have had a previous era of prevalence – but, even so, it had left plenty of susceptible people untouched. 10/-

In 1968 Hong Kong Flu finally pushed Asian Flu aside. It reached Hope-Simpson’s patients in January, 1969, but only managed to attack <5% of the population in 3 months. 11/-

Some speculated that HK Flu had actually infected many more – there must have been symptomless infections in ~40% of the population. Wishful thinking. The following December it returned to attack 3x as many in just six weeks, and returned again in the following years. 12/-

Hope-Simpson was monitoring closely – not just influenza, but also other common diseases. He was testing his own ability to conduct this kind of research, and comparing the local with the national and international pictures. 13/-

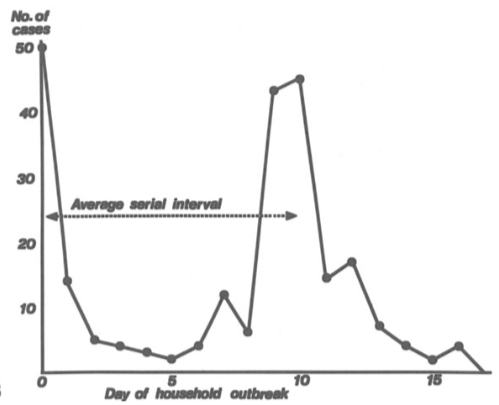

He had recorded measles outbreaks through household studies, monitoring the homes of the sick to see whether others in the house were infected and when. Here we see his plot of such a study, showing clearly the serial interval: the time between cases. 14/-

Serial interval matters. It’s the time between ‘generations’ of an infectious disease, measured from symptom onset in the ‘index’ case to symptom onset in the ‘secondary’ case. It shows that the disease is being transmitted from case to case. 15/-

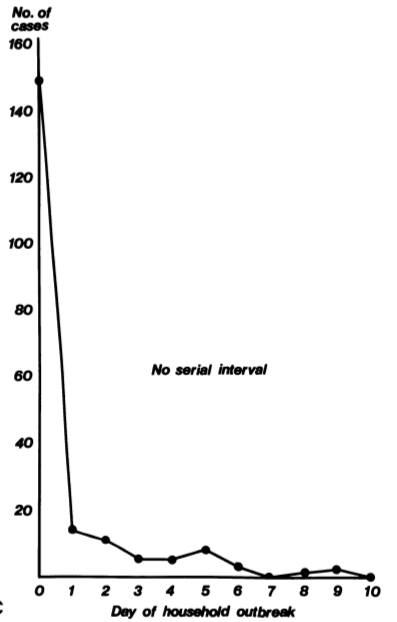

In order to monitor the spread of Hong Kong Flu in 1969, Hope-Simpson conducted another thorough household study. He found that in 70% of households, in which there was an initial infection, there was no further infection. This was not expected. 16/-

As for the serial interval, I guess you, or I, or any 21st century epidemiologist might have diligently calculated the mean interval of these cases and come up with a figure. Hope-Simpson did not. He was a doctor, treating patients and seeing first-hand how disease spread. 18/-

“No serial interval can be demonstrated within affected households,” he wrote. 19/-

Serial interval demonstrates the transmission of the disease from the first group (index cases) to the next (secondaries). If there was no serial interval, there was no way to distinguish index cases, secondaries, tertiaries, etc. 20/-

Hope-Simpson noted that household members of presumed index cases in his study were >4x as likely to become infected as the population at large. The source of infection must be within the house. 21/-

In institutional outbreaks, sometimes ~50% of people had been infected, yet here, in houses with already one case, only 14-17% of household companions were attacked. An implausibly low figure. 22/-

The sick were not infecting their companions (if they were, the serial interval would show), but someone in the house was infecting people. The infector must be someone who was not sick – an asymptomatic carrier. 23/-

If an asymptomatic carrier within the household had infected their companions, including the supposed index cases, then the true secondary attack rate in the first (smaller) outbreak had been 25% and, in the second, 55%; more in line with institutional outbreaks. 24/-

If the virus was being transmitted by asymptomatic carriers, and the infected were unable, themselves, to transmit, then exponential spread would not occur and the outbreak would end when the carriers either ceased to be infectious, or ran out of non-immune companions. 25/-

Hope-Simpson’s ‘new concept’, described in detail in The Transmission of Epidemic Influenza, accounts for 21 holes in the current concept, and makes fascinating reading (it really is very readable). By considering it, we might learn much about our present predicament. 26/26

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter