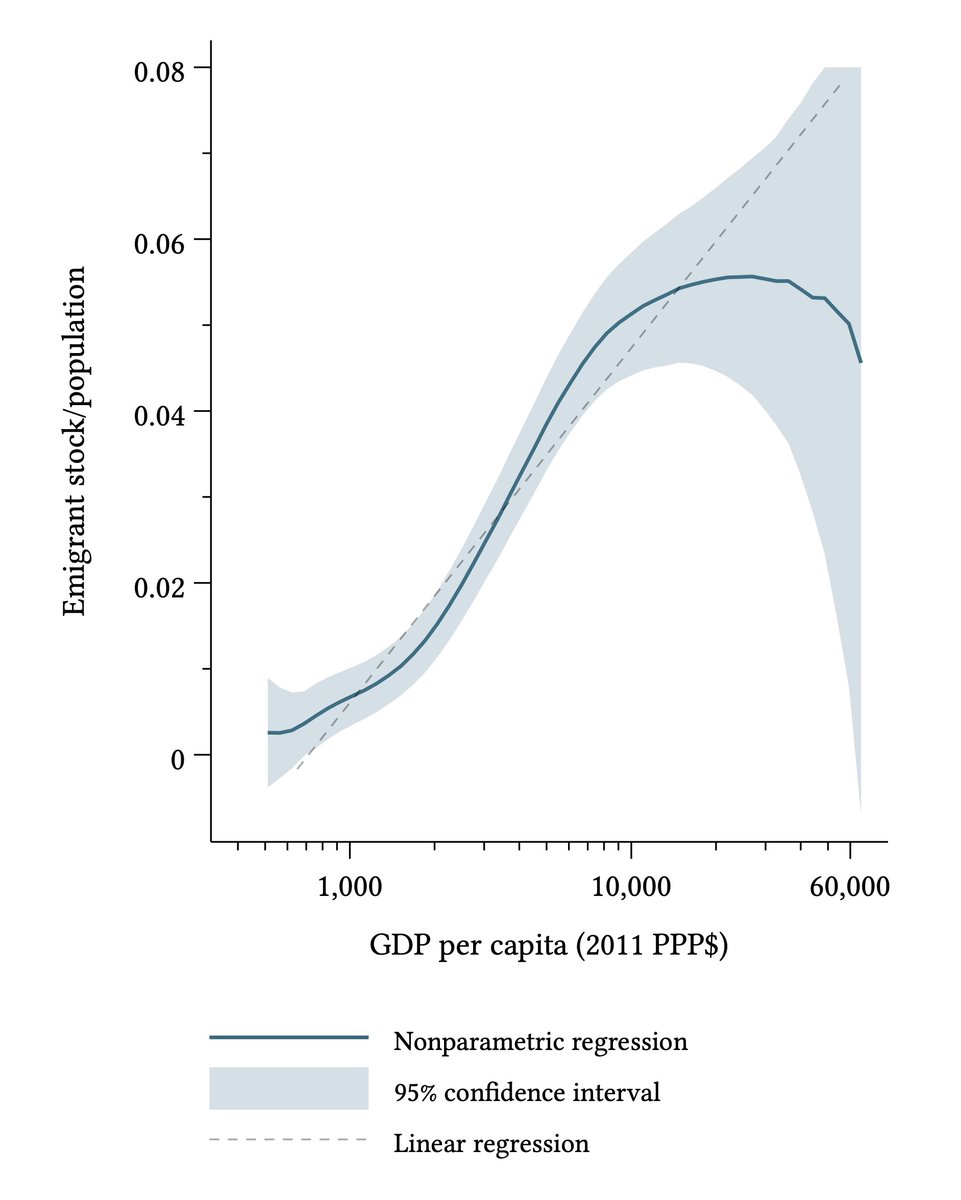

At left, average emigration from developing countries to rich countries, omitting microstates.

The question was raised: But does that snapshot accurately represent the paths they take as they grow?

At right, the paths they took. Yes, it does.

Quick thread ☞

The question was raised: But does that snapshot accurately represent the paths they take as they grow?

At right, the paths they took. Yes, it does.

Quick thread ☞

Both of these figures show emigration from all developing countries (those classified as "low- or middle-income" by the World Bank for most of the period 1960–2019).

They show only emigration to "high-income" countries. They omit microstates (<2.5m population).

They show only emigration to "high-income" countries. They omit microstates (<2.5m population).

They are Figures 1c and 2c in my new paper on the #EmigrationLifeCycle —> https://www.cgdev.org/publication/emigration-life-cycle-how-development-shapes-emigration-poor-countries">https://www.cgdev.org/publicati...

That left-hand figure shows the relationship between the level of GDP/cap. and the level of emigration (emigrants as fraction of home-country population).

The arrows in that right-hand figure show the relationship between *growth* in GDP/cap. and the net *flow* of emigration.

The arrows in that right-hand figure show the relationship between *growth* in GDP/cap. and the net *flow* of emigration.

This is just not a controversial or subtle pattern requiring fancy statistical methods to tease out.

Relatively richer developing countries have tremendously higher emigration prevalence. Developing countries that grow have tremendously higher net outflows of emigrants.

Relatively richer developing countries have tremendously higher emigration prevalence. Developing countries that grow have tremendously higher net outflows of emigrants.

In the language of economics, the sign and broad magnitude of the slope in a pooled country-year panel is highly robust to the inclusion of country effects (fixed or random).

(It& #39;s also robust to a thicket of other specifications, shown in the paper.)

(It& #39;s also robust to a thicket of other specifications, shown in the paper.)

Some questions that could, in principle, be raised:

Is real GDP per capita growth across decades a good measure of a country& #39;s "economic development"?

→ Yes, it absolutely is the best single metric we have.

Is real GDP per capita growth across decades a good measure of a country& #39;s "economic development"?

→ Yes, it absolutely is the best single metric we have.

Is this an accurate measure of emigration?

→ Yes, this is by far the most accurate measure we have. It is based on counting the number of people in every country on earth, born in every other country on earth. It allows us to measure the movement of real people across borders.

→ Yes, this is by far the most accurate measure we have. It is based on counting the number of people in every country on earth, born in every other country on earth. It allows us to measure the movement of real people across borders.

Other measures are misleading. For example, one could count US immigration by an administrative action: green cards issued.

But that does not measure the movement of people! Half of green cards are given to people *already here*.

And that would ignore all irregular migration.

But that does not measure the movement of people! Half of green cards are given to people *already here*.

And that would ignore all irregular migration.

Moreover, green cards don& #39;t contain any information about reverse movement. The US, Greece, and many other countries do not track emigration at all.

+170,000 Mexicans a year receive green cards in the US, but the net flow of Mexicans into the US has been *negative* for years.

+170,000 Mexicans a year receive green cards in the US, but the net flow of Mexicans into the US has been *negative* for years.

Are the migrant population counts accurate?

→ They are based on census, labor force survey, and population register data. They& #39;re the best data out there, with a single commensurable definition of & #39;migrant& #39;. It is possible that they moderately undercount some migrants.

→ They are based on census, labor force survey, and population register data. They& #39;re the best data out there, with a single commensurable definition of & #39;migrant& #39;. It is possible that they moderately undercount some migrants.

It is not at all plausible, however, that they undercount by ~90%. Looking at the graphs above again, for undercounts to generate this pattern spuriously, governments would have to be *selectively* undercounting poor-country migrants >10X. No evidence supports that.

Do politicians care about the size of migrant populations, or just the size of migrant flows?

→ This question is misplaced, because the figures at the top of this thread describe both population size and flow size.

→ This question is misplaced, because the figures at the top of this thread describe both population size and flow size.

The first figure shows prevalence (stocks), the arrows in the second figure show incidence (net flows).

Higher levels of income mean much higher prevalence.

Growth in income goes hand in hand, almost always, with much higher incidence: higher *flows*.

Higher levels of income mean much higher prevalence.

Growth in income goes hand in hand, almost always, with much higher incidence: higher *flows*.

I understand the reluctance to face these very basic and extremely clear facts. They are counterintuitive, and many governments have heavily invested in a different narrative.

I try to address why this is so hard, in this post—> https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it">https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emig...

I try to address why this is so hard, in this post—> https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it">https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emig...

All of this is part of a bigger release of research, some of it with Prof. @MariapiaMendola of @unimib and @iza_bonn, that you might have seen in this week& #39;s Economist —> https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/08/29/the-idea-that-aid-and-development-slow-migration-is-wrong">https://www.economist.com/middle-ea...

It confirms findings from decades of social science work, especially by sociologist @heindehaas and geographer @jorgencarling, who have been teaching all of us for some time.

I summarize a half century of literature on this subject here—> https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/8592/does-development-reduce-migration">https://www.iza.org/publicati...

I summarize a half century of literature on this subject here—> https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/8592/does-development-reduce-migration">https://www.iza.org/publicati...

It is time to move past politically tendentious debates about whether the #EmigrationLifeCycle exists. It exists. There are few clearer patterns in development.

Rather, it is time to discuss how policy will face this reality. My post discusses how—> https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it">https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emig...

Rather, it is time to discuss how policy will face this reality. My post discusses how—> https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it">https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emig...

Thank you very much for engaging with this research. All of you stay safe.

P.S., I should have linked to classic works on this subject by @heindehaas —> https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00435.x

And">https://doi.org/10.1111/j... by @jorgencarling and @CatTalleraas —> https://www.prio.org/Publications/Publication/?x=9229">https://www.prio.org/Publicati...

Recommended for a deep understanding of what underlies this remarkable empirical fact.

And">https://doi.org/10.1111/j... by @jorgencarling and @CatTalleraas —> https://www.prio.org/Publications/Publication/?x=9229">https://www.prio.org/Publicati...

Recommended for a deep understanding of what underlies this remarkable empirical fact.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter