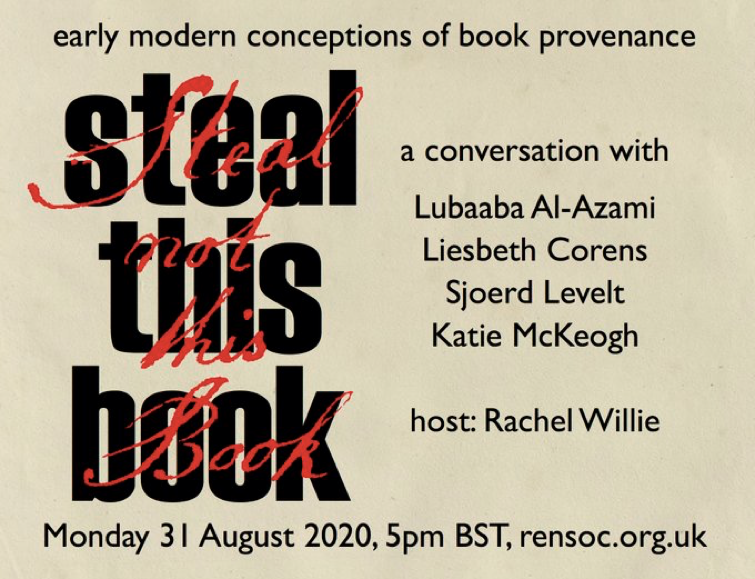

// live tweeting of the below @SRSRenSoc event

we start with @SLevelt introducing us to the Utrecht psalmer and tracing its provenance -- despite being once owned by Robert Cotton, it didn& #39;t end up in the British Library, but in the Netherlands.

This is because Cotton was generous with lending his books -- the library was a "fluid, changing, collection" -- but how did this lead to permanently losing such a valuable manuscript?

Ownership inscriptions offer some clues: the name Mary Talbot appears. We know that Cotton lent some books to the earl of Arundel, some of which were returned, but others which weren& #39;t...

But, as @SLevelt reminds us, such relationships worked two ways. Ownership marks can be traced both ways.

next up is @DrKLMcKeogh (and cat!!) on the library of Sir Thomas Tresham. she points out the importance of chance & serendipity in provenance research -- due to surviving letters, we know what Tresham intended to give to St John& #39;s College, how much he intended to spend ...

... and what he thought about the way that books should be treated. The books are uniformly bound & stamped -- and, with only three exceptions, bought for the purpose of donation.

The stamp, too, seems to have been designed for this donation. (Think about self-fashioning: again, this gift of books works backwards to throw light on the giver.)

Two of the books are inscribed & #39;et amicorum& #39;; they come from Tresham& #39;s own library. Katie suggests that this points us to the notion in provenance of shared ownership -- books might have been owned by individuals, but they still worked within social and intellectual circles...

So, the question of who owns a book is always about so much more.

Which might perhaps reveal why Tresham chose St John& #39;s to donate to - he wasn& #39;t an alum, and had no family connections (although his son might have gone there) - but it had associations with Jesuits such as Campion and was religiously well-aligned with Tresham.

questions of donating books are: what sort of connections do I want to emphasise? What do I want to make? How do I want to appear?

Now we have @onslies! videoing in from a woodworking cellar where magic happens.

she& #39;s interested in the sense of custody of (early modern english) convent texts: these were common properties of the convents, so what concept of & #39;ownership& #39; can be applied? how helpful is it to talk about it at all?

& #39;Custodianship& #39; -- the sense of being a link in a chronological chain both before and after -- might make more sense; the religious house as one stage, looking after the books for the future, from the past.

Liesbeth talks about the sense that continued preservation is an active, ongoing concern -- library as valuable, but also vulnerable -- Augustine Baker& #39;s concern that the house keeps originals as well as transcribing copies, in order to safeguard books for future use.

There& #39;s a sense in Baker& #39;s concern that one copy is being valued more than others -- that there& #39;s a burgeoning sense of the & #39;original& #39;, and the importance of conserving and preserving that.

This results in a catalogue: the urge to preserve Baker& #39;s specific copies becomes in part the urge to uphold the legacy and authority of a & #39;founding figure& #39;. Preserving the originals as approved by Baker also served against the possibility of accusations of unorthodoxy...

Provenance is thinking about lineage, but lineage also implies a future; there is no end-point to it, but the possibility of mobility (in this case, for example, of back across the Channel). It is a responsibility both to the past but also the future.

Finally we have @Lubaabanama on everyone& #39;s favourite slaveowner and OTT collector Sloane (yes this is how I& #39;m referring to him at every point in my PhD)

It& #39;s always worth noting, I think, just how HUGE Sloane& #39;s influence still is in London. Institutions (BL, BM, NHM...) aside, but also infrastructure all over the place. The intertwinings of legacy and provenance is much more than unpicking the way they work in museums.

Lubaaba comments that the proceeds and infrastructure of slavery and trading not only lead directly to these institutions, but benefit us as researchers perhaps more explicitly than anyone else -- is there a need for specific academic self-reflection here?

Quick sidenote: Lubaaba is brilliantly modelling the way that offensive words, and topics such as violence in texts, can be talked about without being made unnecessarily explicit. You don& #39;t need to dwell on the racism of Sloane& #39;s writing of slavery to understand it...

...and if your initial impulse is to revel in it, why? What are you gaining?

What does it mean, Lubaaba asks, to use materials with questionable or troubling provenance? What questions should we be asking as researchers working with these items?

(the recent @britishmuseum decision to move Sloane& #39;s bust and recontextualise it happened alongside the overhaul of his page online; the @britishlibrary bust is also being recontextualised, with a new label written)

But we can& #39;t get just rid of Sloane& #39;s stuff -- nor would anyone want to -- or ignore the history behind it. So, how do we go forward?

Lubaaba suggests that one step forward might be for humanities scholars to think about the ethics and moral foundations of their research in the same way that STEM scholars are routinely and methodologically encouraged to...

So much of the answer starts with visibility: being asked, constantly, to bear in mind the violent histories of provenance, to confront them rather than assume they are not relevant to the work being done...

Start from a position where you assume that provenance history, in all its messiness and discomfort, IS relevant, rather than otherwise.

Some notes from questions:

@SLevelt sums it up by commenting that it is always important to think about what& #39;s missing from the history of provenance. Who gets to own & preserve material is also always a commentary on who doesn& #39;t: who loses the right to conservation?

@SLevelt sums it up by commenting that it is always important to think about what& #39;s missing from the history of provenance. Who gets to own & preserve material is also always a commentary on who doesn& #39;t: who loses the right to conservation?

speaking to the problem of representation within museums, @Lubaabanama asks: how can institutions successfully curate a world they don& #39;t represent?

The discussion of shared ownership, raises the suggestion that early modern ownership might offer a new model of curatorship as we think about rehauling and exploring the way we approach these books today. As @onslies notes, it& #39;s important to think of it as something active...

...which is an ongoing feature of this discussion: curatorship and the study/discussion of provenance aren& #39;t passive acts, nor are they all about the past. We need to think about how we want to pass these books to the future, too.

. @wynkenhimself asks about how book history can benefit from the work of other disciplines. It traditionally sits between English Literature and History departments, but these questions touch on anthropology, on linguistics, cultural history, postcolonial theory...

Maybe one of the benefits of moving & #39;book history& #39; out of either English or History is to give it the space to benefit from a wider sense of & #39;interdisciplinarity& #39;?

(This seems to raise some US/UK divides; here, it is very firmly English-based.)

. @aehdeschaine comments that & #39;I hope that history of the book can be taught more widely but with a global scope, NOT just Western& #39;. Which leads me to my final point: provenance can be decolonised theoretically as well as practically...

... you can practice thinking about familiar material in different ways, teasing out those connections, rather than worrying about the specific history of whatever book next confronts you in the Rare Books Reading Room!

some resources, for further reading:

https://memorients.com"> https://memorients.com

https://reconstructingsloane.org"> https://reconstructingsloane.org

and... I& #39;m just going to plug my own upcoming essay on provenance in @inscription_jnl, which if you& #39;ve read this far I hope you& #39;ll forgive me for!

https://memorients.com"> https://memorients.com

https://reconstructingsloane.org"> https://reconstructingsloane.org

and... I& #39;m just going to plug my own upcoming essay on provenance in @inscription_jnl, which if you& #39;ve read this far I hope you& #39;ll forgive me for!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter