"Are All Managed Care Plans Created Equal? Evidence from Random Plan Assignment in Medicaid"

with @MikeGeruso and @jwswallace

https://www.nber.org/papers/w27762 ">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

Regulated competition between private health plans has become the dominant form of social health insurance in the US, with 69% of Medicaid beneficiaries in a managed care plan and in Medicare 33% in an MA plan and 100% in private Part D plans.

$500 billion of the $1.3 trillion spent on public health insurance programs went to private managed care plans in 2017.

Yet the availability of consumer choice has made it difficult to establish important facts about the plans the government is contracting with. Do plans with observable lower spending (or higher quality) *causally* reduce spending? Or are differences due to selection?

In this paper, we leverage random assignment of Medicaid beneficiaries to plans in NYC to answer these questions.

The setting is important: There are 10 plans that vary on many dimensions of managed care but all plans have NO cost-sharing.

The setting is important: There are 10 plans that vary on many dimensions of managed care but all plans have NO cost-sharing.

We can thus estimate whether & to what extent plans can influence spending w/o the use of cost sharing & then evaluate the tradeoffs of any spending reductions.

Cost-sharing introduces the ubiquitous trade-off between risk protection and moral hazard. But what are the trade-offs of non-cost-sharing tools that reduce spending?

This is important because modern health insurance contracts consist of many dimensions beyond deductibles and copays.

We thus compare tools used by managed care plans to the effects of cost-sharing from prior studies to understand how these tools differ in costs and benefits.

We thus compare tools used by managed care plans to the effects of cost-sharing from prior studies to understand how these tools differ in costs and benefits.

tl;dr - We show that non-cost-sharing tools can achieve LARGE spending reductions *with no increase in financial risk for beneficiaries*.

BUT, like the trade-off between risk protection and moral hazard, there is also a trade-off here, now between spending and quality/health.

BUT, like the trade-off between risk protection and moral hazard, there is also a trade-off here, now between spending and quality/health.

Now, the details:

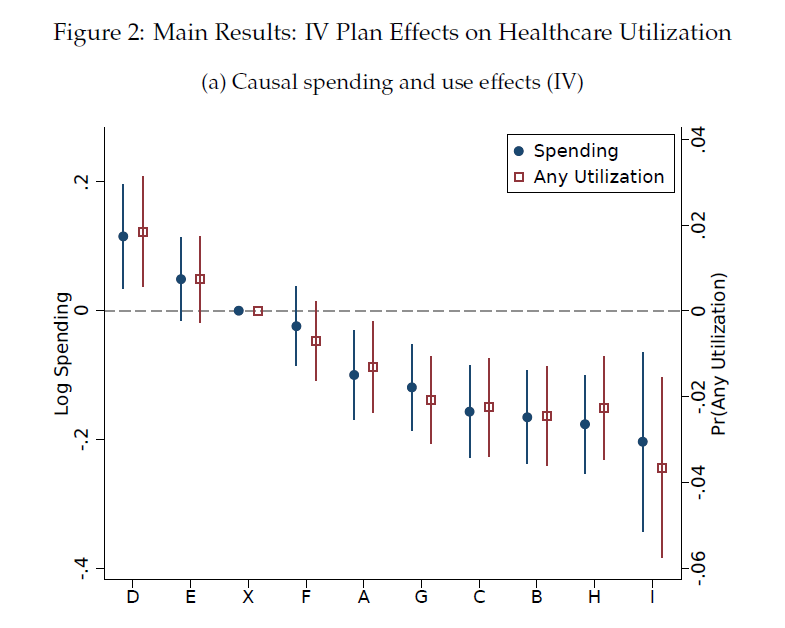

Finding 1: NYC plans with no differences in cost-sharing differ greatly in spending. If a person is enrolled in the highest spending plan in NYC, she will generate over 30% higher spending than if she enrolled in the lowest spending plan.

Finding 1: NYC plans with no differences in cost-sharing differ greatly in spending. If a person is enrolled in the highest spending plan in NYC, she will generate over 30% higher spending than if she enrolled in the lowest spending plan.

That spending gap is 2.5 times the size of the spending difference between a plan where all care is free and a high deductible plan (Brot-Goldberg et al. 2017).

And these Medicaid plans do this with NO difference in cost-sharing.

And these Medicaid plans do this with NO difference in cost-sharing.

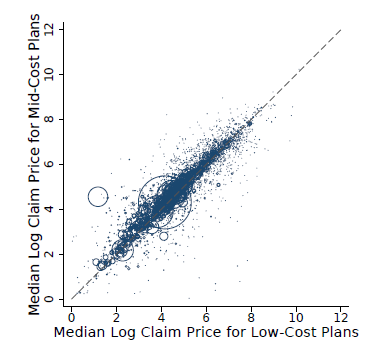

Finding 2: Quantities, not prices, explain the spending gap. Prices differ little between high and low-spending plans (see figure). And estimates of plan effects on price-standardized spending are almost identical to unstandardized effects.

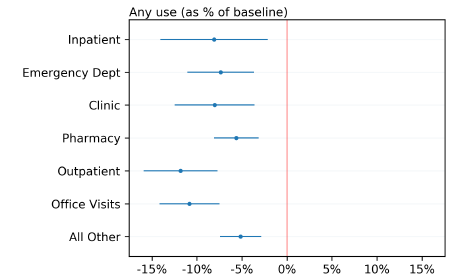

Finding 3: Basically all services are "marginal". While many think of cost-sharing as a "blunt" instrument and tools used by managed care plans as more of a scalpel, targeting low-value services, our evidence suggests otherwise: Managed care tools are as blunt as cost-sharing.

This echos prior work on MA by Vilsa Curto, @liraneinav, Amy Finkelstein, Jon Levin, and Jay Battacharya.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w23090 ">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

https://www.nber.org/papers/w23090 ">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

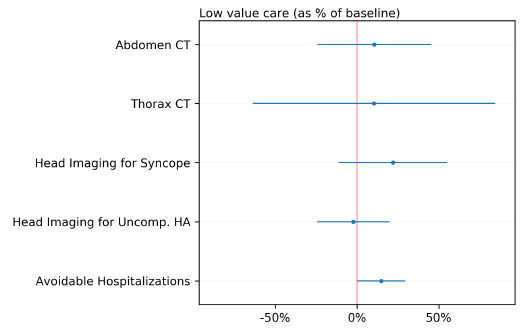

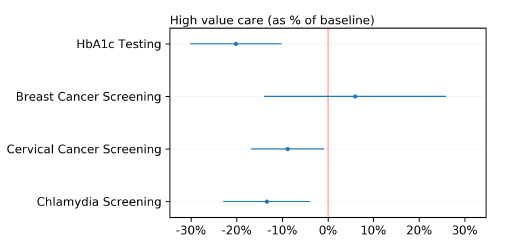

Following work by @zarekcb, @amitabhchandra2, @BenHandel, and @jtkolstad we look specifically at high-value and low-value care. We find that

3a: Low-spending plans DO NOT target low-value services identified by @A_Schwa et al.

3a: Low-spending plans DO NOT target low-value services identified by @A_Schwa et al.

3b. Low-spending plans DO reduce the use of high-value services, such as HbA1c testing and various cancer screenings.

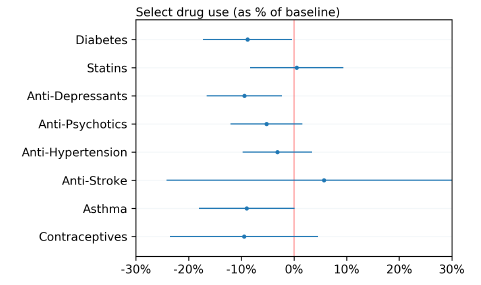

3c. Low-spending plans DO reduce the use of many high-value drugs, such as drugs to treat diabetes, anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, asthma meds, and contraceptives.

Finding 4: There are REAL tradeoffs of the spending reductions achieved by low-spending plans

4a (health): These plans cause a significant increase in avoidable hospitalizations

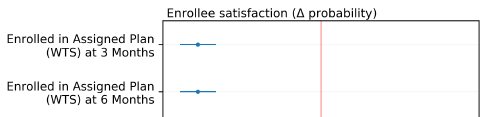

4b (satisfaction): Ppl assigned to these plans are more likely to switch out of them post-assignment

4a (health): These plans cause a significant increase in avoidable hospitalizations

4b (satisfaction): Ppl assigned to these plans are more likely to switch out of them post-assignment

Summary: We show that non-cost-sharing tools can achieve LARGE spending reductions *with no increase in financial risk for beneficiaries*.

BUT, like the trade-off between risk protection and moral hazard, there is also a trade-off here, now between spending and quality/health.

BUT, like the trade-off between risk protection and moral hazard, there is also a trade-off here, now between spending and quality/health.

BUT, while the healthcare spending/quality tradeoff exists, there is NO tradeoff for the state: For a given person, NY Medicaid pays all plans the same risk-adjusted $$. Thus, for these markets to function, we need to identify plans with good outcomes and steer ppl to those plans

As the US shifts more and more social health insurance programs to private managed care plan markets, the conversation will likely move away from a focus on poor financial protection provided by high deductible plans and instead toward plans that produce bad outcomes.

Also, go check out awesome related work by @Jabaluck, @autoregress, @AmandaStarc1, and @mmcaceresb who study variation across MA plans in causal mortality effects!

https://www.nber.org/papers/w27578 ">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

https://www.nber.org/papers/w27578 ">https://www.nber.org/papers/w2...

Now, to end, this paper has been in the works for something like 5 years, starting back when I was a postdoc and @jwswallace was a grad student and we shared an office. It made it through multiple births, house purchases, new jobs, etc.

It has come so far since then and been so full of headaches and successes. So many times we thought we were close to done and then proven wrong yet again. Quasi-random administrative auto-assignment is both a blessing and a curse people.

You always want it when you don& #39;t have it but when you get it you don& #39;t know what to do with it...

Fortunately, I couldn& #39;t ask for better co-authors who made this difficult journey at least enjoyable with so many dad-jokes, delicious meals, etc. Thanks guys. Here& #39;s to many more.

Fortunately, I couldn& #39;t ask for better co-authors who made this difficult journey at least enjoyable with so many dad-jokes, delicious meals, etc. Thanks guys. Here& #39;s to many more.

Thanks to @Arnold_Ventures and @AHRQNews for supporting this project!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter