Erik Wade ( @erik_kaars) here again! I am again not really going to talk about my own work, but about the history of scholarship, specifically the history of scholars of the early Middle Ages suggesting that scholars shouldn& #39;t use the term "Anglo-Saxon." #MedievalTwitter

This debate has raged on for over a hundred years, though it may seem to be fairly recent. Because it& #39;s often described as a recent, politicized argument, it might be useful to discuss its deeper history.

Let& #39;s start in 1861, just after the death of historian Sir Francis Palgrave, whose third volume of The History of Normandy and England came out posthumously around this time, and which included a strong argument against the historical use of the term "Anglo-Saxon."

Palgrave stated baldly that there was no "Anglo-Saxon nation" and there was no "Anglo-Saxon language." If one asked an Englishman from before the Norman Conquest what his language was called, Palgrave argued, he would have answered "English."

In 1867, historian Edward Freeman publishes the first volume of his The History of the Norman Conquest of England. In an appendix, Freeman lays out his argument against the use of the term "Anglo-Saxon" to describe the early medieval English.

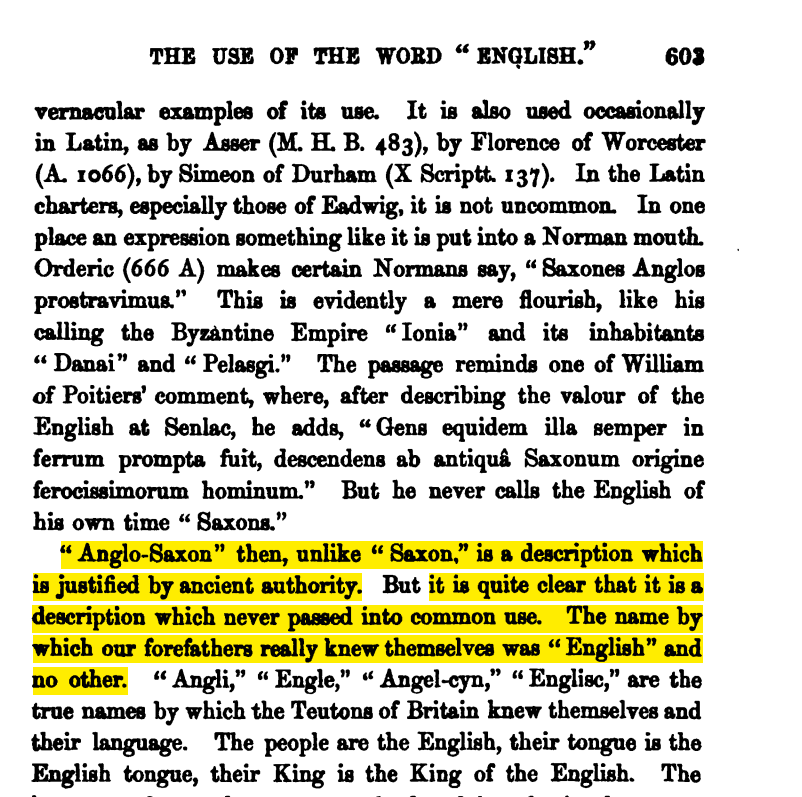

Freeman argues that they should be called the English bc that& #39;s what they called themselves: "I hold it to be a sound rule to speak of a nation, as far as is possible, by the name by which it called itself."

Freeman argues that the English of the first millenium rarely used the term "Anglo-Saxon," and only in Latin, while variations of term "English" appear in Latin and Old English.

Freeman& #39;s own argument against the term reveals the complicated politics and nationalism that has followed these debates from the beginning.

He repeatedly evokes a transhistorical Anglo-Saxon race, arguing that the "Ango-Saxon period is still going on" and thus the term is useless as a chronological marker.

He also closes by quoting the Palgrave passage from above.

He also closes by quoting the Palgrave passage from above.

Let& #39;s flash forward to 1929, when medievalist Kemp Malone published a semantic study of the word "Anglo-Saxon."

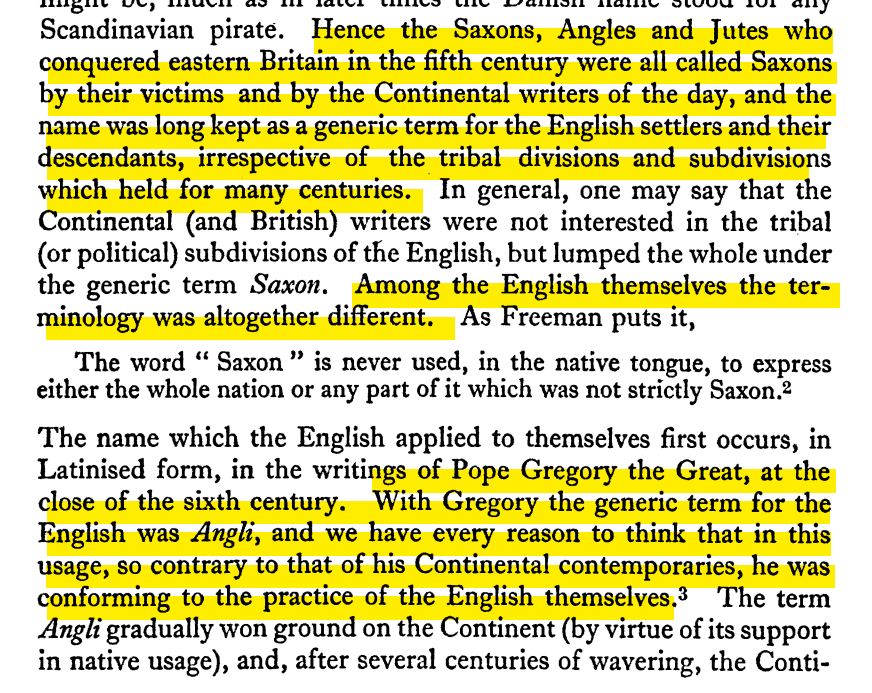

Malone also argued that the term used by the early medieval English for themselves was "English." Some non-English called them the "Saxons," but their own name for themselves was consistently "English."

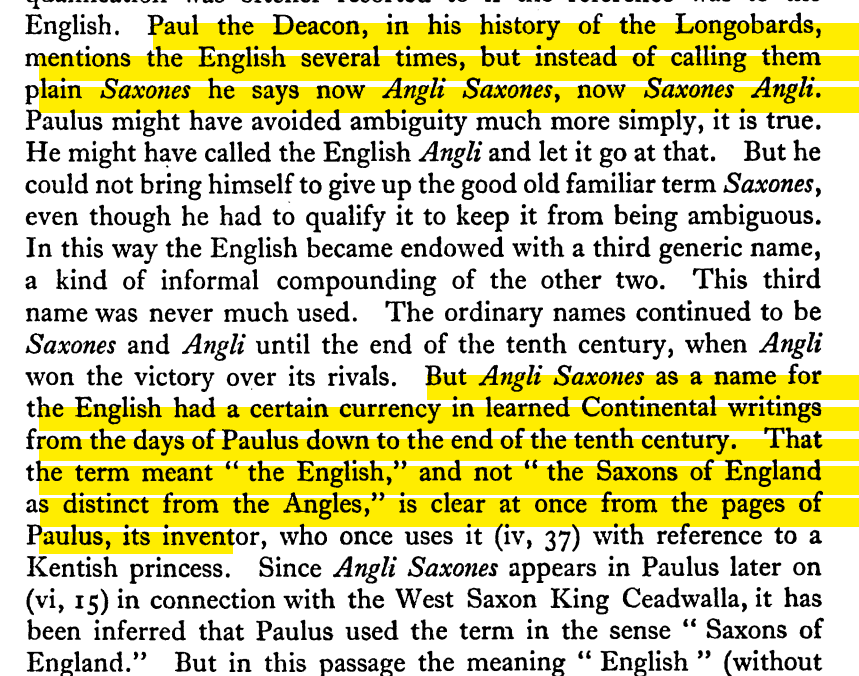

Malone traced the term "Anglo-Saxon" to the continent, first to Paul the Deacon, then spreading throughout continental writers.

The term arrived in England via Asser the Welshman, at King Alfred& #39;s ninth century court, Malone argues. Alfred himself may not have used it at all, just Asser when referring to Alfred.

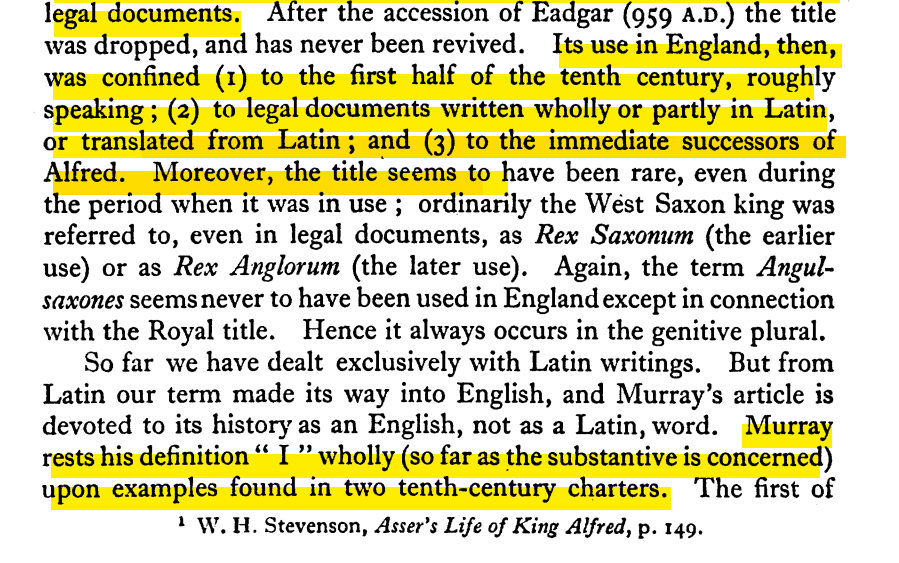

Malone summarizes thusly: the term appears in English documents almost only in Latin, almost only in the first half of the 10th century, and in documents from the court of Alfred or his *immediate successors.* Even there, the term is rare.

Malone surveys the evidence for the term in Old English and finds three (3) instances only, all in documents either translated from Latin or written in a mixture of Latin and OE. The term was thus not likely part of the vernacular.

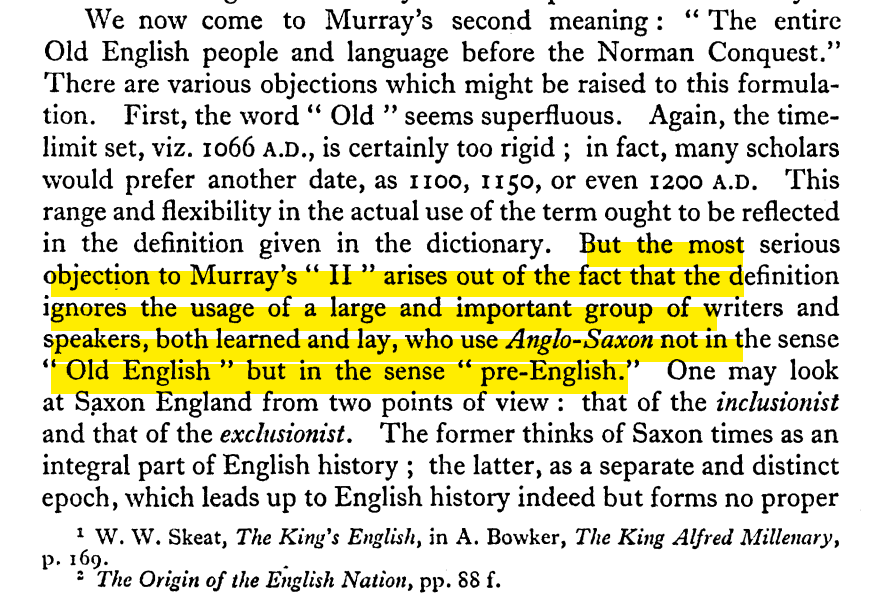

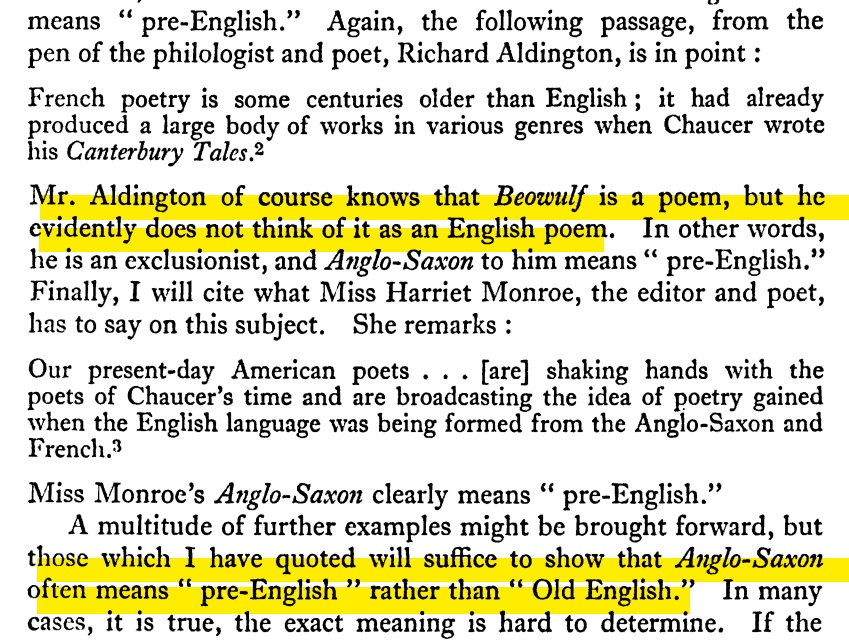

After this flurry of medieval semantic study, Malone turns to the modern, where he presents his second major objection to using the term "Anglo-Saxon": not only is it not the term the English used, its modern use seems designed to partition off the early medieval period.

Malone argues that medievalists and scholars refer to the "Anglo-Saxon period" or the "Anglo-Saxon language" as pre-English, or as not properly part of the history of England or the English language.

These debates continued for decades, with scholars like Susan Reynolds & Hirokazu Tsurushima (screenshot pictured, from his Nations in Medieval Britain) arguing that the term was not particularly common in the period in question & asking why it was common practice to use it.

There are MANY racial narratives surrounding the term "Anglo-Saxon." This has been summarized elsewhere at length, so I won& #39;t belabor it, but texts by Reginald Horsman, Cedric Robinson, and one last year by Matthew Vernon have summarized racial Anglo-Saxonism.

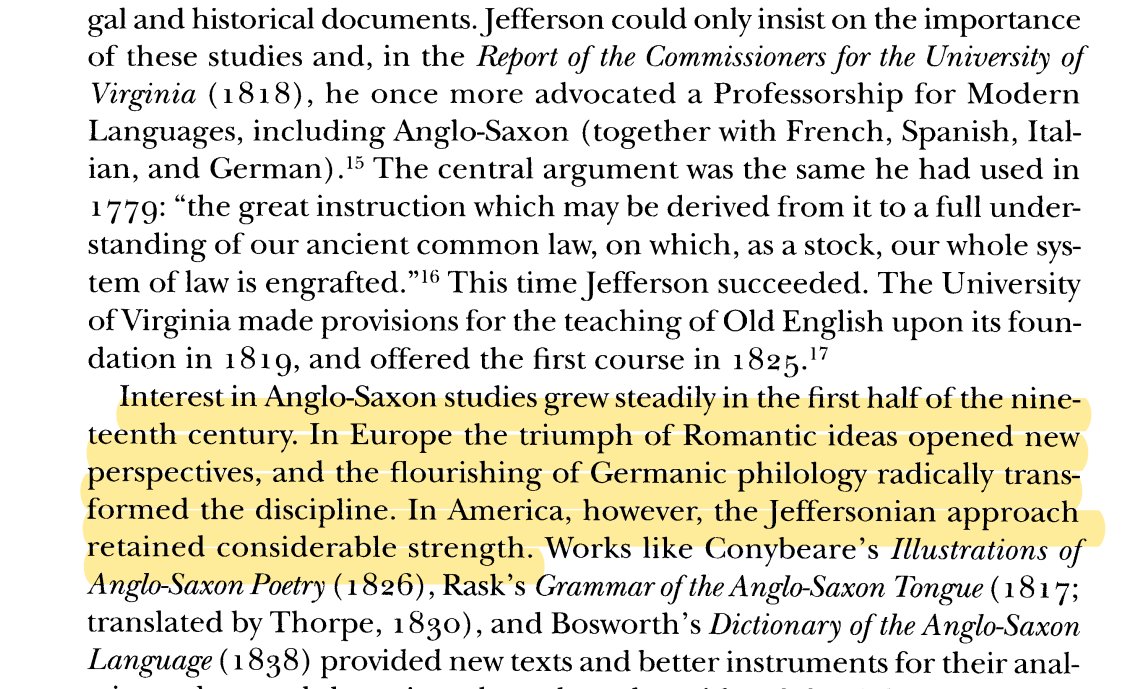

In America, its rise was tied to narratives about the historical early medieval English, as María José Mora and María José Gómez-Calderón pointed out. Thomas Jefferson, like many, pushed for study of the period as he connected it to a historical myth of the origins of common law.

Though scholars pointed these racial connotations out in the 1980s, it took almost thirty years for medieval studies to start to take them seriously. Medievalists began calling for another term & suggesting that the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists (ISAS) change its name.

In 2019, Dr Mary Rambaran-Olm resigned from the board of the ISAS, citing their gatekeeping, treatment of scholars of color, sheltering of sexual predators, lack of a harassment policy. She also suggested that they change their name.

In the aftermath, the society voted to change its name (something already in the works), bc of the racial baggage of "Anglo-Saxon." Narratives about this reduced Dr. MRO& #39;s larger critique of the org to her calling for a name-change, which caught the attention of the media.

Starting with the Washington Post, media orgs began to run articles on the name-change, often featuring pictures of Dr. MRO and painting her as the instigator of the change. This resulted in a massive series of attacks on her and her scholarship.

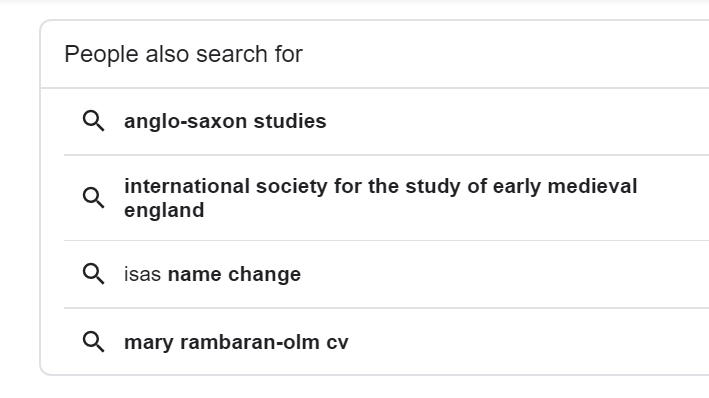

The personalized and targeted nature of this has perhaps no clearer symbol than these suggested searches from Google from when I searched "Anglo-Saxon ISAS" today.

Note "mary rambaran-olm cv" - what does her scholarship have to do with this debate? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

Note "mary rambaran-olm cv" - what does her scholarship have to do with this debate?

This is WAY too long of a thread bc I cannot ever be short, but I hope this shows how long this debate has gone on, and what it signifies about academia & the racial baggage of "Anglo-Saxon" that a Black scholar was so targeted for saying what white scholars had said.

Erik Wade here with an addendum, since there was confusion. I do *not* mean that the news articles were attacks on Dr. MRO, as that was not the case. Indeed, the Daily Beast article, for instance, supported the change. The point is that the news coverage led to attacks by others.

My apologies for the unclarity and for seeming to suggest that the articles were attacks.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" title="The personalized and targeted nature of this has perhaps no clearer symbol than these suggested searches from Google from when I searched "Anglo-Saxon ISAS" today. Note "mary rambaran-olm cv" - what does her scholarship have to do with this debate? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" title="The personalized and targeted nature of this has perhaps no clearer symbol than these suggested searches from Google from when I searched "Anglo-Saxon ISAS" today. Note "mary rambaran-olm cv" - what does her scholarship have to do with this debate? https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>