On the topic of imperial Iranian inscriptions circulating among subjects, a postscript which takes us to the Sasanian Empire, a case of scholarly integrity, & fascinating modern forgeries. Though less known, it is as instructional as the now infamous Gospel of Jesus& #39; Wife. 1/15

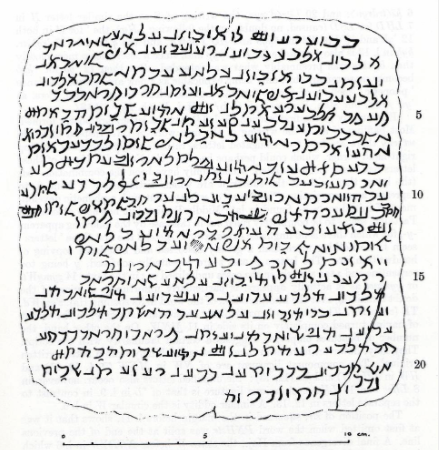

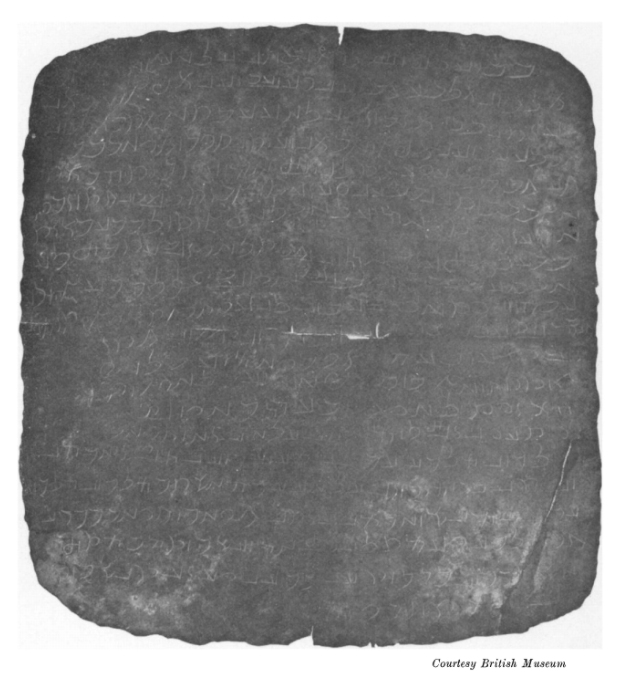

In 1978, the Iranist David MacKenzie published a new edition and translation of the Sasanian king Shapur I& #39;s bilingual (Parthian and Middle Persian) inscription at Hajjiabad. He incorporated a new source: a silver plaque found @britishmuseum with the same inscription. 2

This seemed to be a similar phenomenon to the Aramaic copy of an Achaemenid inscription from 700 years earlier; this time, a copy of the monumental rock inscription had been circulated, and functioned as a prestige object for some Sasanian inhabitants. 3 https://twitter.com/Simcha_Gross/status/1298752043801337856">https://twitter.com/Simcha_Gr...

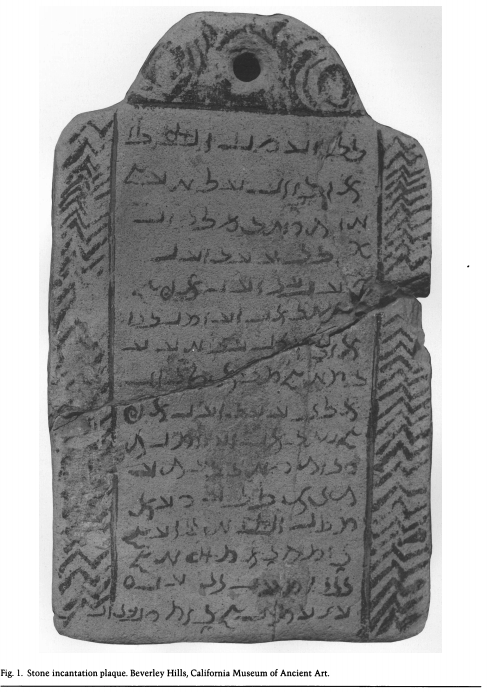

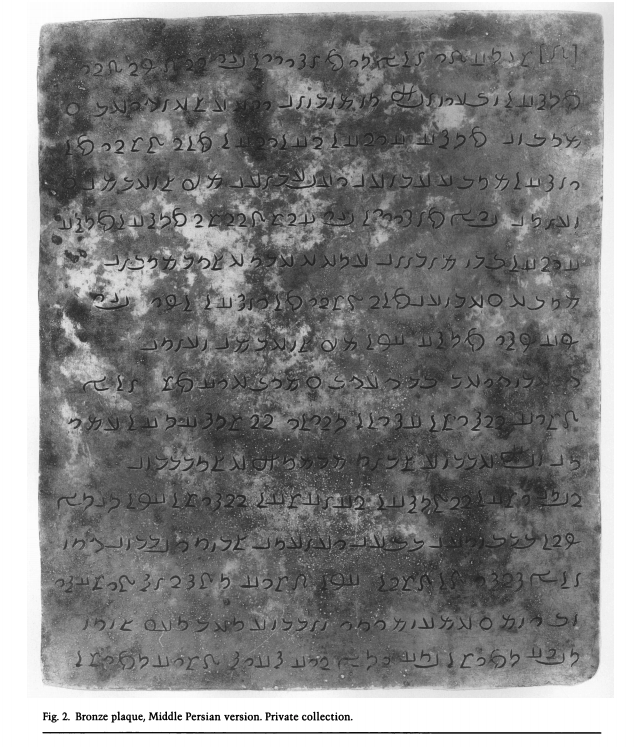

Over the next few decades, the Hajjiabad inscription continued to reemerge on new items; a stone plaque, bronze plaques (one of Parthian and one of the Middle Persian), & from @Yale a ceramic bowl that in form was identical to the famous Aramaic incantation bowls. 4

At this point you should begin hearing alarm bells; only one inscription (Hajjiabad) continued to reemerge, and of all the inscriptions, it was a strange choice, as it mostly detailed Shapur& #39;s feats of archery... 5

In 1990, the great Iranist Oktor Skjaervo (one of my teachers) published the earthenware bowl with the Hajjiabad inscription. When I read this many years ago, I was thrilled; at last tangible proof of imperial propaganda reaching its (perhaps Jewish & Christian) subjects! 6

But as I read on, Skjaervo began noting his own creeping suspicion about the item& #39;s authenticity which, in a moment of scholarly honesty and integrity, he said emerged from the fact that when he first tried to publish the bowl, it was rejected by a very learned reviewer. 7

The reader noted that he had at this point seen a number of items inscribed with the Hajiabad inscription - the ones I listed above - and it was clear that they were fakes. 8

Now, as you might imagine, the field of Iranian linguistics is not a terribly crowded one, and Skjaervo quickly realized that there was only one other scholar who would have seen texts and artifacts not shown to him; the great Iranist and Semiticist, Shaul Shaked. 9

But wait, if Skjaervo& #39;s article had been rejected, then how was I reading it? Well, both Skjaervo and Shaked published their articles in the same issue of the Bulletin of the Asia Institute in 1990. 10

There, Shaked explained how he knew these were all forgeries; they all had the same mistakes! When MacKenzie had only seen one such copy of the Hajjiabad inscription, these mistakes had actually lent it credence as an authentic copy with typical scribal errors & unique forms. 11

But when viewed in aggregate, it was clear these mistakes pointed to a common source. Indeed, these items were in the same hand... A bit of research yielded the answer; the very same mistakes appeared in Ernst Herzfeld& #39;s 1924 edition of the inscription. Case closed. 12

This is first and foremost a story about scholarly integrity, and two of the leading scholars in their field using peer review and communication in pursuit of the best published results. 13

But it also means there is still an undiscovered forger out there who has employed much the same methods as the one& #39;s detailed in @arielsabar& #39;s new book about the Gospel of Jesus& #39; Wife. And this forger is still out there, unidentified. 14

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter