Aesthetic Science - THE THREAD:

In 15 tweets, I& #39;m going to explain my new book Aesthetic Science. Its about the period 1650-1720, when natural philosophers (closest thing to scientists back then) put increased emphasis on using the senses to understand the natural world. 1/15

In 15 tweets, I& #39;m going to explain my new book Aesthetic Science. Its about the period 1650-1720, when natural philosophers (closest thing to scientists back then) put increased emphasis on using the senses to understand the natural world. 1/15

Adopting this empirical method wasn& #39;t necessarily the obvious thing to do. After all, the senses often tell us things that are downright false. Moreover, they can lead us into error because sensory experiences come with pleasure and pain. 2/15

The people I write about - characters like Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, and John Ray - totally bought into these worries about the senses. They needed to find a way of making the unruly, embodied senses into fit instruments for the production of reliable knowledge. 3/15

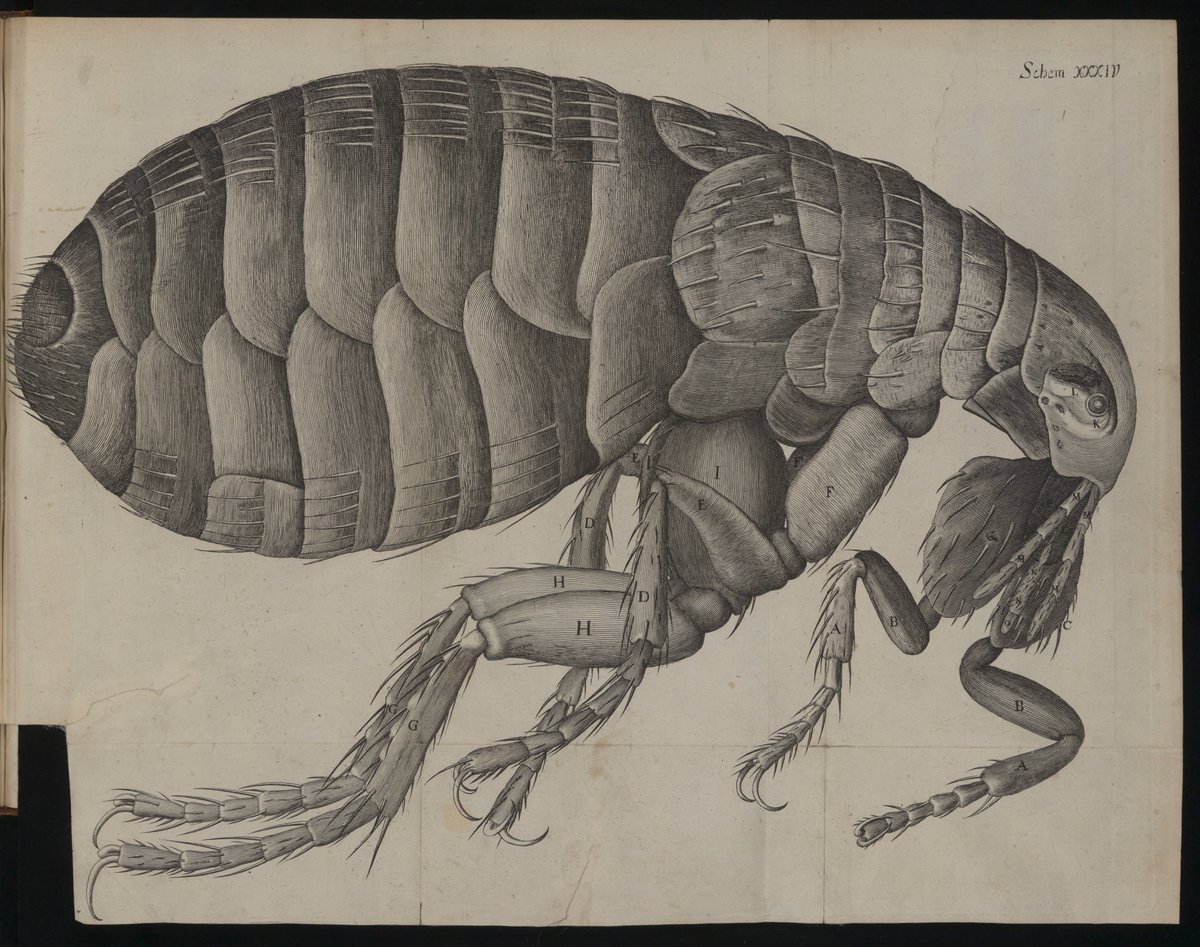

Traditionally, historians have argued that the scientists of the 17th century responded to this challenge by trying to make the senses dispassionate, disciplining the senses through scientific method. But challenges to this claim have emerged from historians working on 4/15

the links between science and literature, and at the links between science and art. In both cases, they& #39;ve noticed natural philosophers using powerful, affective images to communicate scientific ideas. A classic example is the lovely flea included by Robert Hooke in his 5/15

Micrographia of 1665. In Aesthetic Science, I go a step further by showing that character such as Hooke saw the empirical sciences as exercises in cultivating the right kinds of feelings towards the objects of scientific study. They didn& #39;t want to discipline the senses into 6/15

dispassionate neutrality. They wanted natural philosophers to feel the bodily and mental pleasures that corresponded to the discovery of the truth. With this argument, I make some new suggestions about the links between the arts and sciences in the 17th and 18th centuries 7/15

First, I argue that British scientists of 1650-1720 were keenly interested in what we would call aesthetics and taste - they were interested in getting people to agree about the affective dimensions of experience, about their pleasures and pains. Indeed, I think that some 8/15

of the close connections between science, medicine, and aesthetics in the early 18th century can be explained in those terms. Second, I argue that the religious arguments made by natural philosophers such as Boyle, Hooke, and Ray were much more important to their scientific 9/15

practices than has so far been realized. They saw nature as the product of God& #39;s design, and claimed that experiencing that design would cause pleasure. In Aesthetic Science (I won& #39;t give away the examples here) we see that they didn& #39;t just make those claims in religious 10/15

contexts. They actually practiced a science that looked for beauty in natural things, frequently rejecting the evidence of their senses when it didn& #39;t conform to their aesthetic of nature. So Aesthetic Science is also partly a book about science and religion, showing 11/15

how religious ideas - and more importantly religious feelings - were encoded into scientific practices through attempts to *feel* the right way about natural things. Finally, I argue for a much closer integration between studies on literature & science, and art & science 12/15

My book shows that people like Boyle and Ray saw written texts as important sources of visual images, sometimes just as potent as pictorial images. They didn& #39;t adhere to our distinctions between word and image. That& #39;s one reason why I chose the title Aesthetic Science - to 13/15

show that I was focusing neither on literature or art, but rather on a regime of scientific-religious experience that natural philosophers put together through a wide array of practices and disciplines, including texts, images, theology, the neurosciences and more 14/15

If any of this appeals, Aesthetic Science is available now, here https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo46479577.html">https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books... and here https://www.amazon.com/Aesthetic-Science-Representing-Society-1650-1720/dp/022668086X.">https://www.amazon.com/Aesthetic... I& #39;d also be very happy to participate in a class if you want to set my book! 15/15

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter