Loved all the generous responses to the question below. Thank you.

Here& #39;s the current structure of the argument on "new forms of organization in public administration (as a response to a changing environment)" (subject to - *a whole lot of* - change)

[Thread]

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> https://twitter.com/dannybuerkli/status/1297481832112566275">https://twitter.com/dannybuer...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> https://twitter.com/dannybuerkli/status/1297481832112566275">https://twitter.com/dannybuer...

Here& #39;s the current structure of the argument on "new forms of organization in public administration (as a response to a changing environment)" (subject to - *a whole lot of* - change)

[Thread]

(Note that this is for an audience which is inside government but is primarily composed of pragmatic practitioners, so this isn& #39;t the Association of People Who Are Deeply Into Public Administration Theory or what have you)

Max Weber changed our ideas about public admin, as did New Public Management. The obvious implication is that they can change again.

("Passierschein A38" for the German speakers) ">https://youtu.be/GI5kwSap9...

( @tobyjlowe, I hope you will forgive me for not being sufficiently radical here)

While NPM has been pronounced dead more times than I can count it still is alive & well in many corners.

E.g: https://anneepolitique.swiss/prozesse/58847-postauto-skandal

tl;dr:">https://anneepolitique.swiss/prozesse/... semi-public public transport entity is subjected to quasi-market mechanisms, is also expected to be profitable, ends up committing fraud.

E.g: https://anneepolitique.swiss/prozesse/58847-postauto-skandal

tl;dr:">https://anneepolitique.swiss/prozesse/... semi-public public transport entity is subjected to quasi-market mechanisms, is also expected to be profitable, ends up committing fraud.

Incentives rule behaviour.

If you tax people by the brick, they& #39;ll start using larger bricks.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick_tax

(via">https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bric... @BLADT)

If you tax people by the brick, they& #39;ll start using larger bricks.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick_tax

(via">https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bric... @BLADT)

Interlude: there& #39;s a very contemporary analogue to this problem in Machine Learning called "reward hacking" where an algorithm finds very creative, unanticipated ways of violating the spirit though not the letter of a reward function. https://twitter.com/vkrakovna/status/980786258883612672">https://twitter.com/vkrakovna...

See this thread for a couple more examples of incentives generating perverse results in public service delivery in depressingly predictable ways: https://twitter.com/dannybuerkli/status/1292011591609745408">https://twitter.com/dannybuer...

Also, for a much more thorough and evidence-based review of the effects of NPM see Christopher Hood& #39;s and @ruth_dixon& #39;s work the effects of NPM in the UK.

tl;dr: it was not a smashing success.

https://www.oao.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/aktuelle_temaer/TILLID/Hood_NPM_i_30_aar.pdf">https://www.oao.dk/fileadmin...

tl;dr: it was not a smashing success.

https://www.oao.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/aktuelle_temaer/TILLID/Hood_NPM_i_30_aar.pdf">https://www.oao.dk/fileadmin...

Disclaimer: it& #39;s easy to be snarky when you haven& #39;t had to contend with how bad (some) public services were before NPM. While the effects may have been questionable some (though clearly not all) NPM advocates had noble objectives.

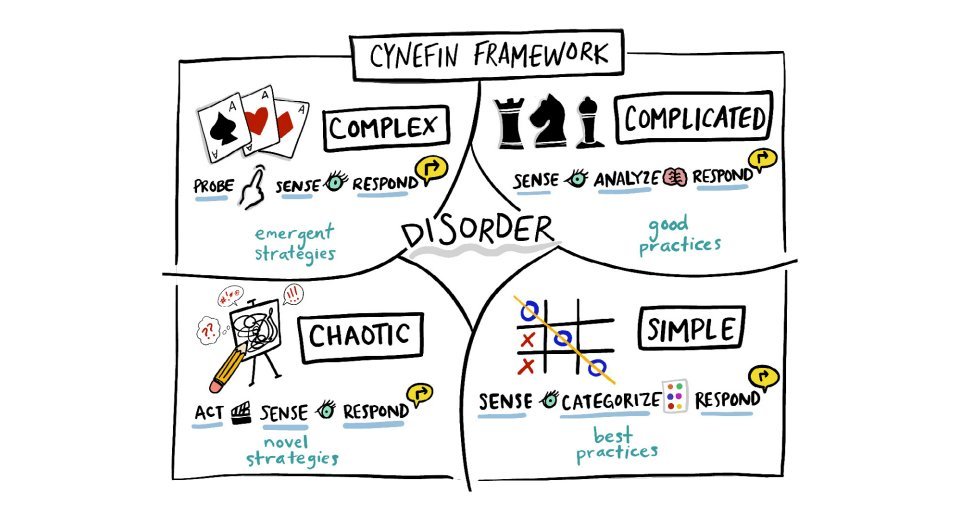

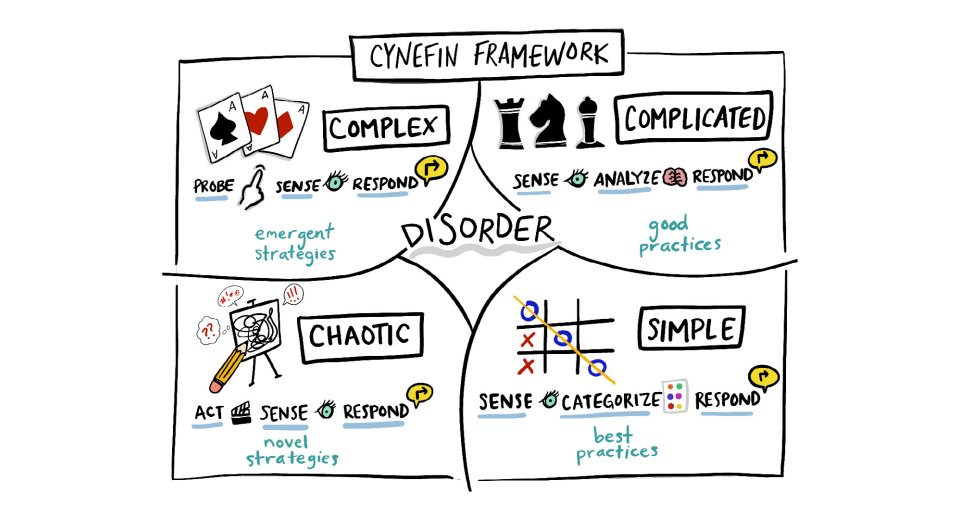

You see, reductionist, scientific management-y systems *may* work in simple or complicated environments but they are guaranteed to fail in complex environments.

What& #39;s the diff. between complicated and complex?

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⏰" title="Wecker" aria-label="Emoji: Wecker"> Complicated things are like clocks. You can take one apart, study the many pieces, understand how they interlock and from that learn how a clock works. Clocks operate in predetermined ways.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⏰" title="Wecker" aria-label="Emoji: Wecker"> Complicated things are like clocks. You can take one apart, study the many pieces, understand how they interlock and from that learn how a clock works. Clocks operate in predetermined ways.

Cats are organisms and their behaviour emerges from interactions between what’s happening inside a cat as well as between that and a cat’s environment.

(I owe this analogy to @markwfoden and his excellent podcast: https://markfoden.com/clockcat )">https://markfoden.com/clockcat&...

(I owe this analogy to @markwfoden and his excellent podcast: https://markfoden.com/clockcat )">https://markfoden.com/clockcat&...

For straightforward outsourcing to work you need to define the outcome of interest in a reasonably non-gameable way (otherwise you can& #39;t write a contract or agree on how the supplier will get paid)

This works (sometimes) for things that are simple or complicated. It is doomed for anything that& #39;s complex.

Hence the outsourcing of driver& #39;s licenses can work just fine ( https://eu.azcentral.com/story/money/business/consumer/2015/04/29/arizona-adot-expands-privatization-drivers-licenses/26558043/)">https://eu.azcentral.com/story/mon... whereas...

Hence the outsourcing of driver& #39;s licenses can work just fine ( https://eu.azcentral.com/story/money/business/consumer/2015/04/29/arizona-adot-expands-privatization-drivers-licenses/26558043/)">https://eu.azcentral.com/story/mon... whereas...

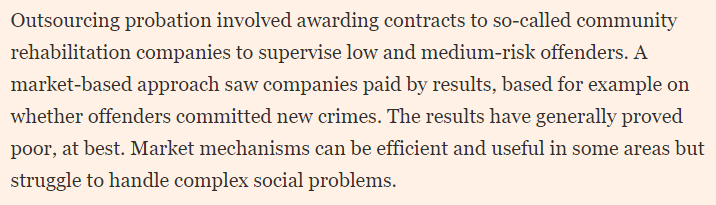

...the outsourcing of complex, relational services like probation services is utterly doomed.

Don& #39;t take it from me, take it from the @FinancialTimes:

( https://www.ft.com/content/fc193e58-2e0d-11e9-ba00-0251022932c8)">https://www.ft.com/content/f...

Don& #39;t take it from me, take it from the @FinancialTimes:

( https://www.ft.com/content/fc193e58-2e0d-11e9-ba00-0251022932c8)">https://www.ft.com/content/f...

(Source of the image: )

- Simple is the domain of best practice

- Complicated is the domain of experts

- Complex is the domain of emergence

- Chaotic is the domain of rapid response

(Source: https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making)">https://hbr.org/2007/11/a...

- Complicated is the domain of experts

- Complex is the domain of emergence

- Chaotic is the domain of rapid response

(Source: https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making)">https://hbr.org/2007/11/a...

Our language is still shaped by the industrial age, which is why we, for example, speak of & #39;policy levers& #39; or of the & #39;machinery of government& #39;.

This is misleading because there are no levers.

We may frantically pull levers but they& #39;re not connected to anything (or, as @_AdrianBrown would say, they& #39;re occasionally connected to a mallet which whacks you in the face).

There are however better metaphors available, we& #39;ll get back to that.

There are however better metaphors available, we& #39;ll get back to that.

Education, any social welfare intervention (e.g. job centres), economic policy, and much more arguably belong in that category.

Another argument is that due to the increased interconnectedness and speed of things many policy domains have, if anything, become more complex.

So let& #39;s focus on those complex domains for a minute.

So let& #39;s focus on those complex domains for a minute.

It& #39;s difficult to be against evidence but what & #39;evidence-based& #39; often ends up looking like, is more centralised and less reliant on non-codified forms of expertise and knowledge.

In simple and complicated environments (pre-existing) evidence may work, in complex ones it doesn& #39;t.

In simple and complicated environments (pre-existing) evidence may work, in complex ones it doesn& #39;t.

Here& #39;s a long-form explanation for why that is the case: https://medium.com/centre-for-public-impact/how-we-know-when-decentralization-works-in-government-7299bd7d8f50">https://medium.com/centre-fo...

Another piece of evidence is Dan Honig& #39;s ( @rambletastic) work on the effects of top-down control vs. discretion in international development work.

tl;dr: in complex environments top-down control harms effectiveness https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_power_of_letting_go">https://ssir.org/articles/...

tl;dr: in complex environments top-down control harms effectiveness https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_power_of_letting_go">https://ssir.org/articles/...

I honestly don& #39;t know. But there& #39;s a lot of interesting experimentation out there.

On their own none of these may feel like a & #39;complete& #39; answer, but if you squint at everything taken together a pattern might start to emerge.

OneTeamGov is interesting for many reasons. One of them is the emphasis on principles as the guide for action.

https://www.oneteamgov.uk/principles ">https://www.oneteamgov.uk/principle...

This aligns well with working in complexity. In a complex domain you cannot, by definition, work with rules which are meant to anticipate every situation. So you work with principles instead.

Andy Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, put it this way:

"As you do not fight fire with fire, you do not fight complexity with complexity. Because complexity generates uncertainty, not risk, it requires a regulatory response grounded in simplicity, not complexity."

"As you do not fight fire with fire, you do not fight complexity with complexity. Because complexity generates uncertainty, not risk, it requires a regulatory response grounded in simplicity, not complexity."

(Source: https://www.bis.org/review/r120905a.pdf)">https://www.bis.org/review/r1...

[It& #39;s getting late over here - to be continued]

Postscript to the & #39;evidence& #39; point above: @theasnow is, of course, right.

Evidence and data is hugely important in complexity, what doesn& #39;t work is mechanically relying on something that worked & #39;over there& #39; and assuming that it will work & #39;here& #39;. https://twitter.com/theasnow/status/1297649284804878336">https://twitter.com/theasnow/...

Evidence and data is hugely important in complexity, what doesn& #39;t work is mechanically relying on something that worked & #39;over there& #39; and assuming that it will work & #39;here& #39;. https://twitter.com/theasnow/status/1297649284804878336">https://twitter.com/theasnow/...

They push authority to where the information is (i.e. in the periphery with the individual carers/nurses) rather than spend time carrying information up a hierarchy to where the authority sits.

(This language comes from @ldavidmarquet)

(This language comes from @ldavidmarquet)

Their way of working also enables a focus on the *relationships* between nurses and clients/patients which in turn increases satisfaction on all sides.

(This may be not v interesting to everyone in the Anglosphere but the lessons from GDS, of which there are many, haven& #39;t been absorbed everywhere)

When you *genuinely* focus on the user the implications are radical. It means not just changing how your website looks but how you organise the work.

(Source: https://mikebracken.com/blog/the-strategy-is-delivery-again/)">https://mikebracken.com/blog/the-...

(Source: https://mikebracken.com/blog/the-strategy-is-delivery-again/)">https://mikebracken.com/blog/the-...

There are many examples of these, including the US Presidential Innovation Fellows program, @Work4Germany_ and @Tech4Germany, or the Entrepreneurs d’Intérêt Général in France.

I& #39;m less clear on the benefits of these (vs. the risks of alienating the & #39;core& #39; org by bringing in high-status outsiders who get to do the flashy work) but anything that makes public administration organisation more permeable would seem to be A Good Thing.

Wigan had to make brutal cuts to its budget in 2011 but found a way of reconfiguring its services around the needs of communities and residents. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/wigan-deal">https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publicati...

The Wigan story isn& #39;t straightforward but it points to the immense potential that can be unlocked with strong, value-based leadership and a shared purpose and ethos.

What do they have in common, if anything?

They seem to collectively point towards a different way of doing things.

It& #39;s a way of doing things which:

- relies on subsidiarity (i.e. gives authority to the periphery, if in doubt),

- puts relationships first,

- experiments with new, unorthodox ways of organising, and

- builds a culture of continuous learning

- relies on subsidiarity (i.e. gives authority to the periphery, if in doubt),

- puts relationships first,

- experiments with new, unorthodox ways of organising, and

- builds a culture of continuous learning

(More on this here: https://resources.centreforpublicimpact.org/production/2019/07/WEB-CPI-Shared-Power-Principle.pdf">https://resources.centreforpublicimpact.org/productio...

plus also in @tobyjlowe& #39;s outstanding "Human Learning Systems" work: https://www.humanlearning.systems/ )">https://www.humanlearning.systems/">...

plus also in @tobyjlowe& #39;s outstanding "Human Learning Systems" work: https://www.humanlearning.systems/ )">https://www.humanlearning.systems/">...

It& #39;s also a way of doing things which emphasises different metaphors. Rather than thinking of government as an engineer who operates a complicated machine  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔧" title="Schraubenschlüssel" aria-label="Emoji: Schraubenschlüssel"> we might think of it as a gardener who tends to a garden

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔧" title="Schraubenschlüssel" aria-label="Emoji: Schraubenschlüssel"> we might think of it as a gardener who tends to a garden  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌿" title="Kräuter" aria-label="Emoji: Kräuter">.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌿" title="Kräuter" aria-label="Emoji: Kräuter">.

Many desirable policy outcomes are emergent properties of complex systems, which is why the gardening metaphor may be apt.

You can create the conditions for desired outcomes to emerge but you cannot directly make them happen any more than you can make a plant grow by pulling on it.

- #1: Central to distributed

- #2: Analog to digital, human to machine

- #3: Scarcity to surplus, closed to open

- #4: Normative to formative, compliant to creative https://twitter.com/dannybuerkli/status/1064575258886373381">https://twitter.com/dannybuer...

That& #39;s it, for now.

The joy and danger of outlining something like this publicly on Twitter is that brilliant and kind people like @theasnow and @_AdrianBrown start pointing out potential flaws and ways to improve them.

The joy and danger of outlining something like this publicly on Twitter is that brilliant and kind people like @theasnow and @_AdrianBrown start pointing out potential flaws and ways to improve them.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="6⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 6" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 6"> Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )">

Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="6⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 6" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 6"> Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )">

Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="6⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 6" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 6"> Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )">

Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="6⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 6" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 6"> Another incredibly helpful way to think about these distinctions is @snowded& #39;s Cynefin framework.(Source of the image: )">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="2⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 2" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 2"> First up, @OneTeamGov, a community of reform-minded civil servants.OneTeamGov is interesting for many reasons. One of them is the emphasis on principles as the guide for action. https://www.oneteamgov.uk/principle..." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="1⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 1" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 1">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="2⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 2" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 2"> First up, @OneTeamGov, a community of reform-minded civil servants.OneTeamGov is interesting for many reasons. One of them is the emphasis on principles as the guide for action. https://www.oneteamgov.uk/principle..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="2⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 2" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 2"> First up, @OneTeamGov, a community of reform-minded civil servants.OneTeamGov is interesting for many reasons. One of them is the emphasis on principles as the guide for action. https://www.oneteamgov.uk/principle..." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="1⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 1" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 1">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="2⃣" title="Tastenkappe Ziffer 2" aria-label="Emoji: Tastenkappe Ziffer 2"> First up, @OneTeamGov, a community of reform-minded civil servants.OneTeamGov is interesting for many reasons. One of them is the emphasis on principles as the guide for action. https://www.oneteamgov.uk/principle..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>