I want to talk about an important new study on racial disparities in infant survival, from @RRHDr & colleagues.

The tl;dr: Black infants in the US are less likely to die when they have a Black pediatrician vs a white pediatrician. https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/08/12/1913405117">https://www.pnas.org/content/e...

The tl;dr: Black infants in the US are less likely to die when they have a Black pediatrician vs a white pediatrician. https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/08/12/1913405117">https://www.pnas.org/content/e...

I’ve seen a surprising amount of criticism of this study from researchers claiming it can’t be used to understand causal relationships.

I disagree and I’d like to explain.

I disagree and I’d like to explain.

First, a brief overview of the study. That there are racial disparities in infant mortality are well-established in the US, with Black infants considerably more likely to die than white infants.

This new study seeks to go beyond simply descibing the disparity to understanding where it might be coming from — or even better, to try to identify interventions that could *reduce* the disparity.

Identifying & estimating effects of interventions is at the core of causal inference. To determine how to estimate causal effects, my preferred approach is the target trial framework.

The authors appear to also have this mindset (even if implicitly), based on their supplement.

The authors appear to also have this mindset (even if implicitly), based on their supplement.

The target trial framework requires that we think about what the ideal randomized trial would be that would provide an estimate of our causal effect of interest.

This is also useful when evaluating papers which try to make causal claims.

This is also useful when evaluating papers which try to make causal claims.

This step is the key to understanding the paper. The authors say their ideal trial would randomize *physicians* to deliver babies, so that they could compare survival of infants who randomly are delivered by a physician of the same or different race.

Often, studies like this are criticized b/c we cant intervene on race. Here, the authors explicitly acknowledge they aren’t interested in the effect of *race*. Instead, race is a PROXY for the actual cause—racism—and they want to know if they can intervene to negate this effect.

So, what about the criticisms this study has received? One I’ve seen come up several times is that in the absence of randomization, it’s not feasible to believe the effect of interest can be validly estimated here.

Let’s take a closer look at this claim.

Let’s take a closer look at this claim.

Randomization serves 2 purposes. First, it ensures people could have been in either intervention group (called “positivity”). Instead, we have to assume all babies could have, in theory, been seen by either a Black or white pediatrician. Thats not guaranteed, but its reasonable.

Second, randomization ensures that the reason a baby is seen by a physician of a particular race has nothing to do with how likely that baby was to live or die in general (called “confounding”). This is tricky to establish in a non-randomized study, but is it unreasonable here?

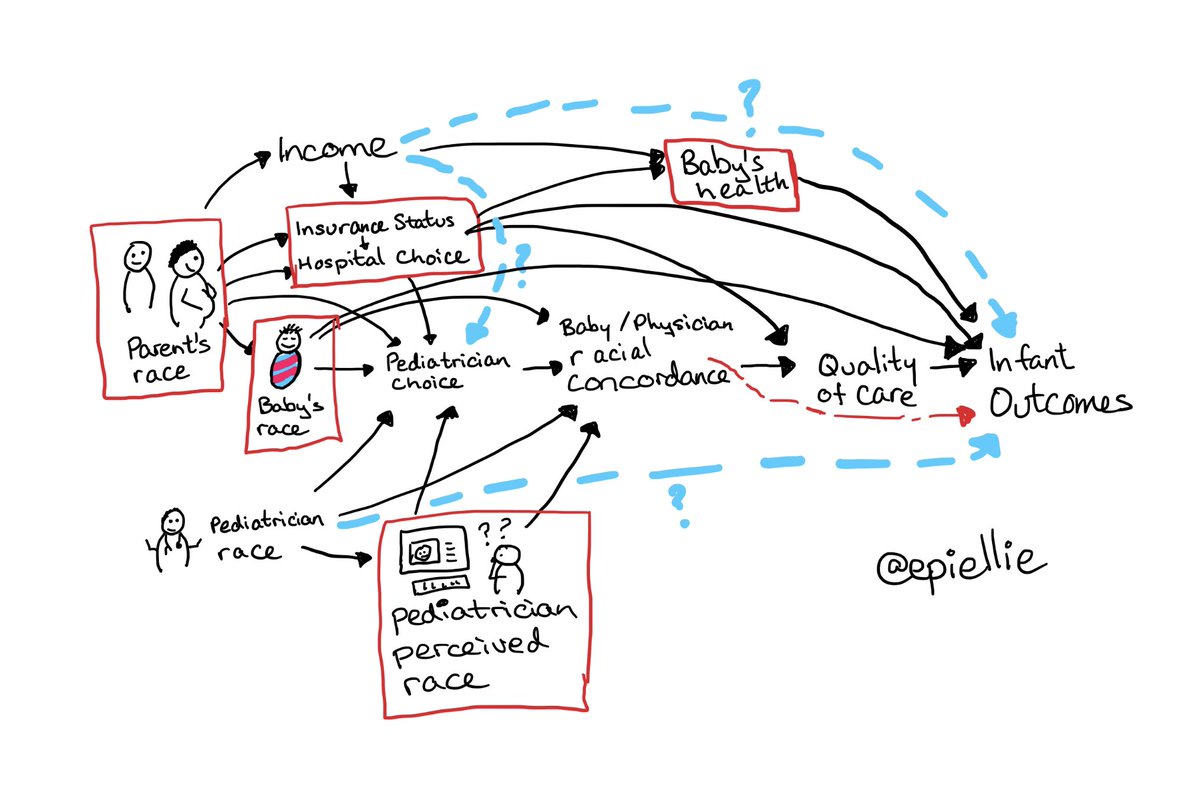

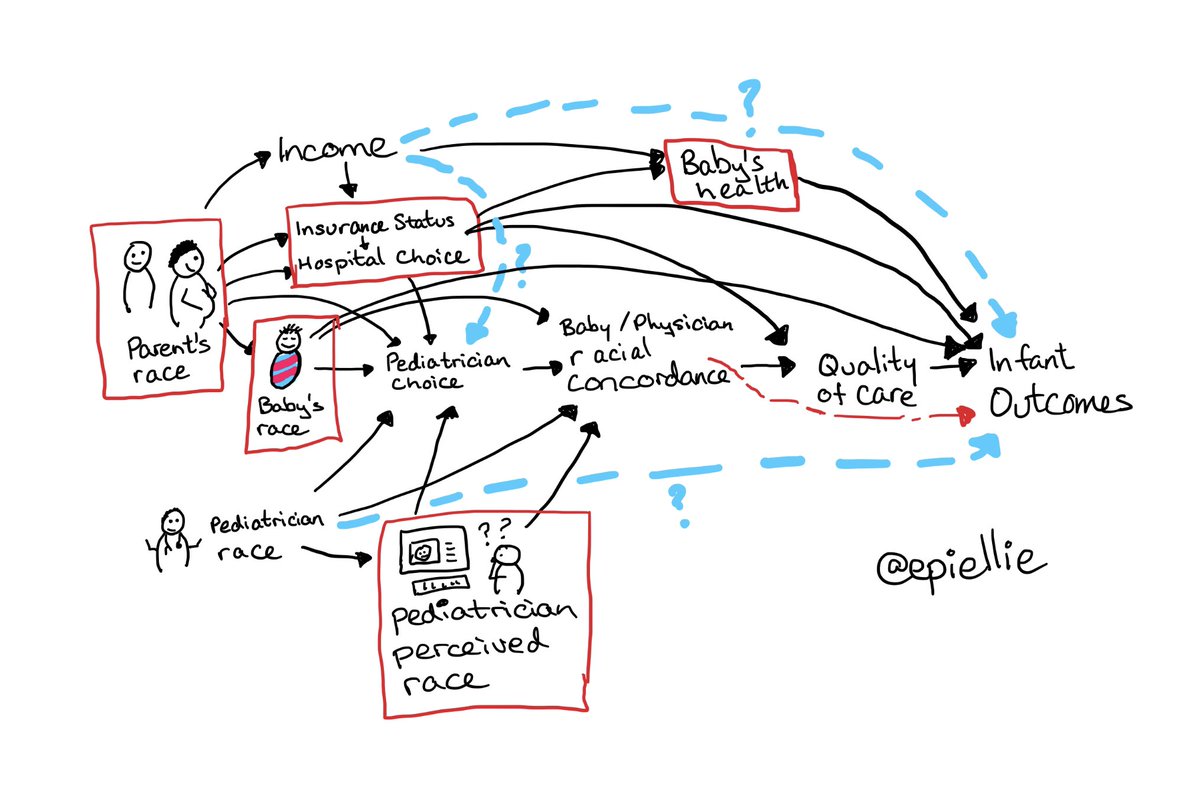

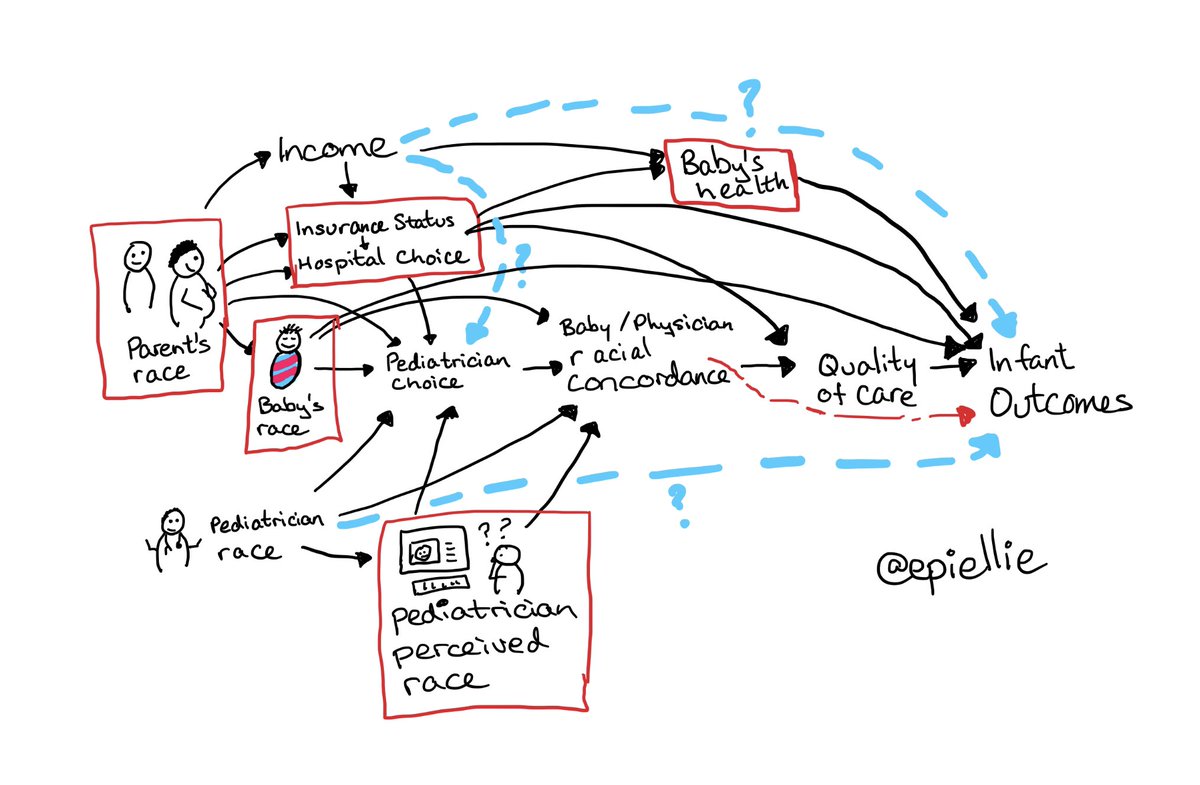

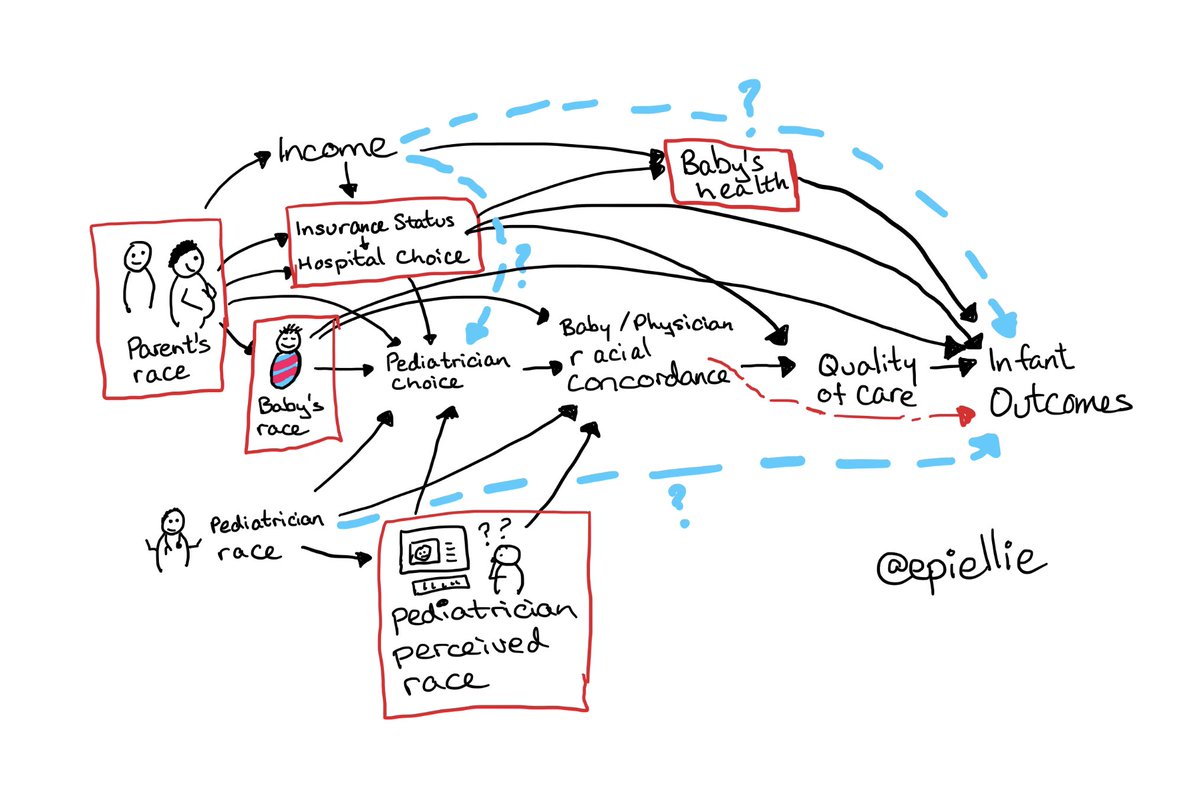

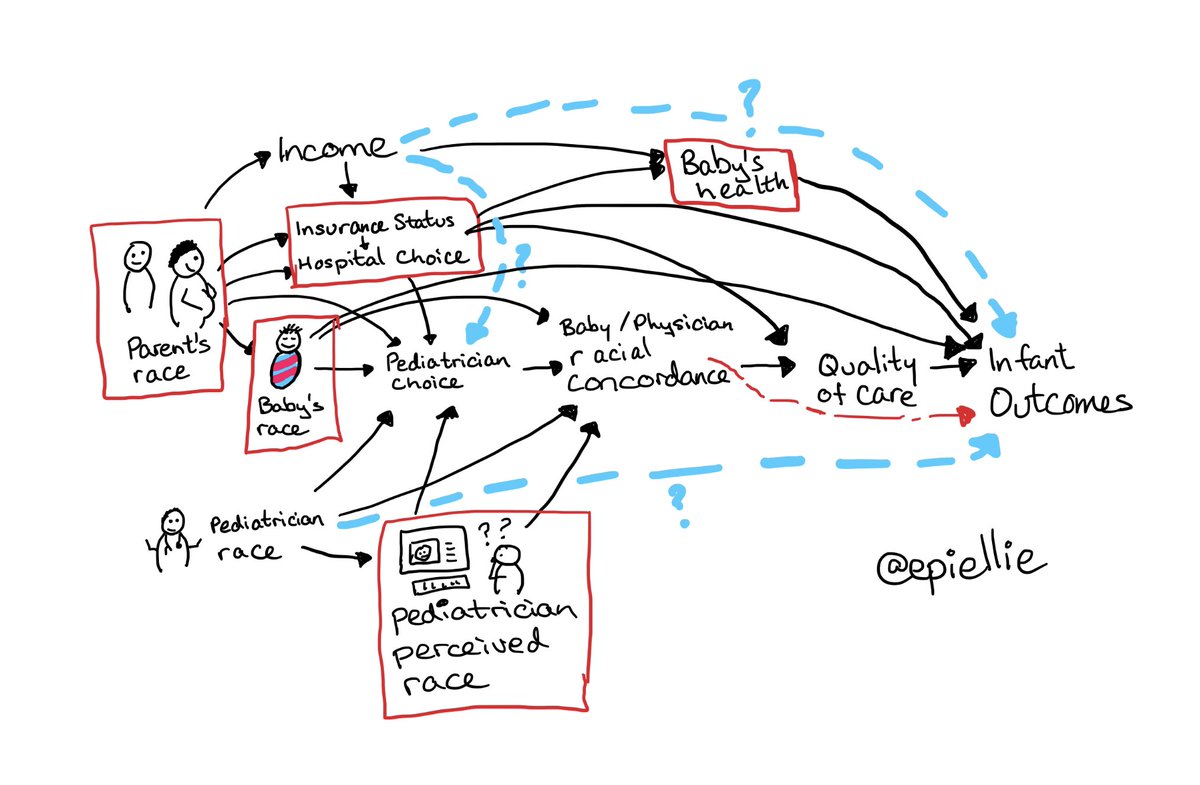

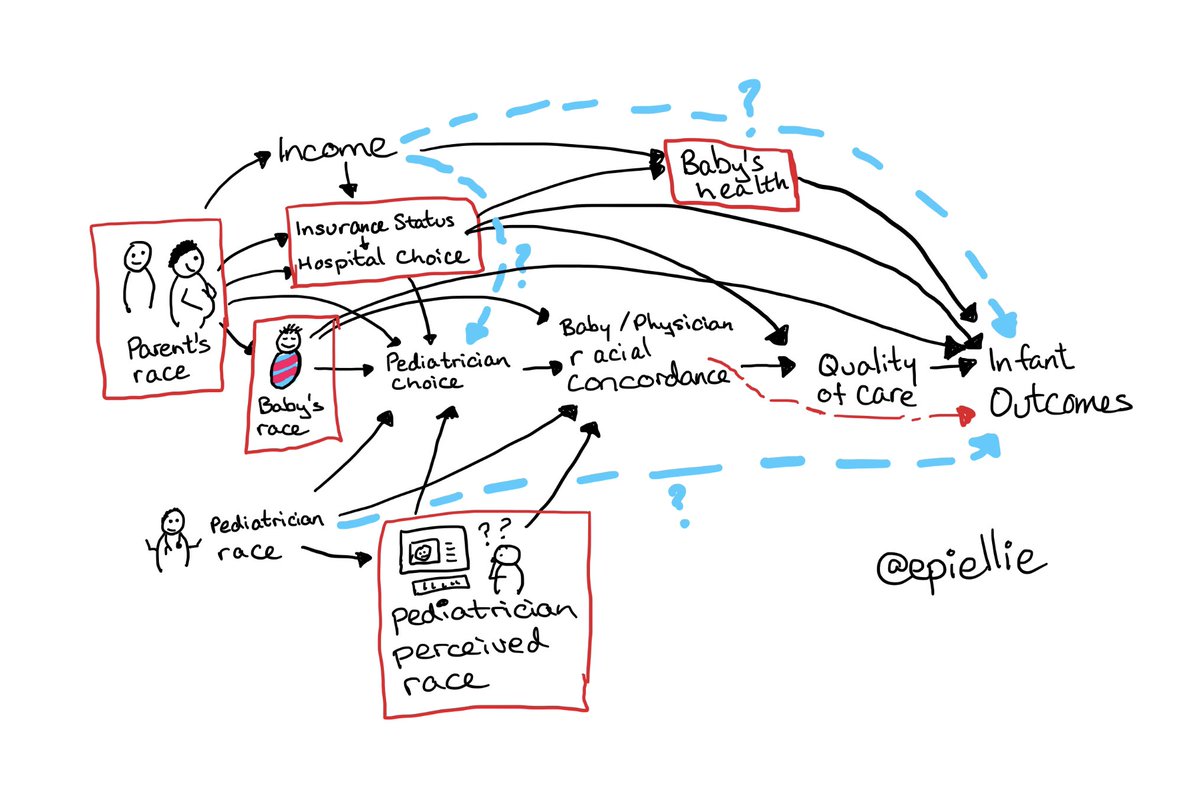

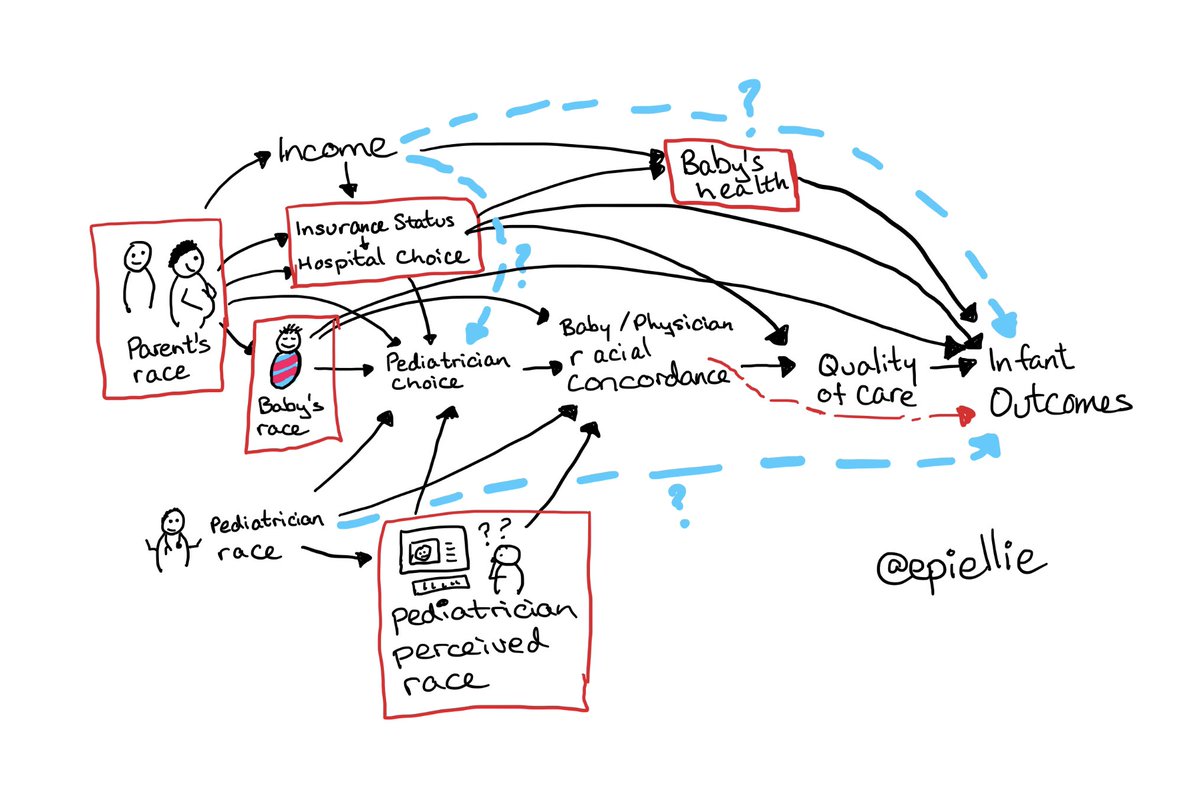

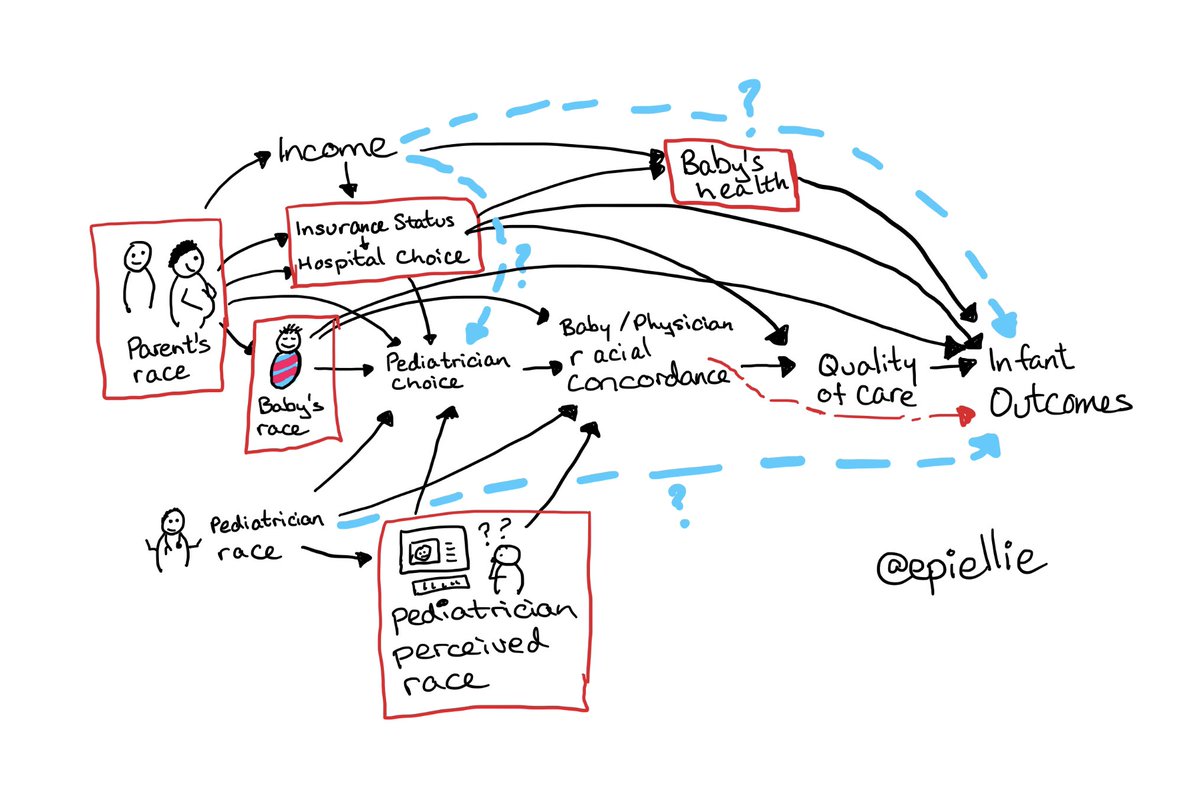

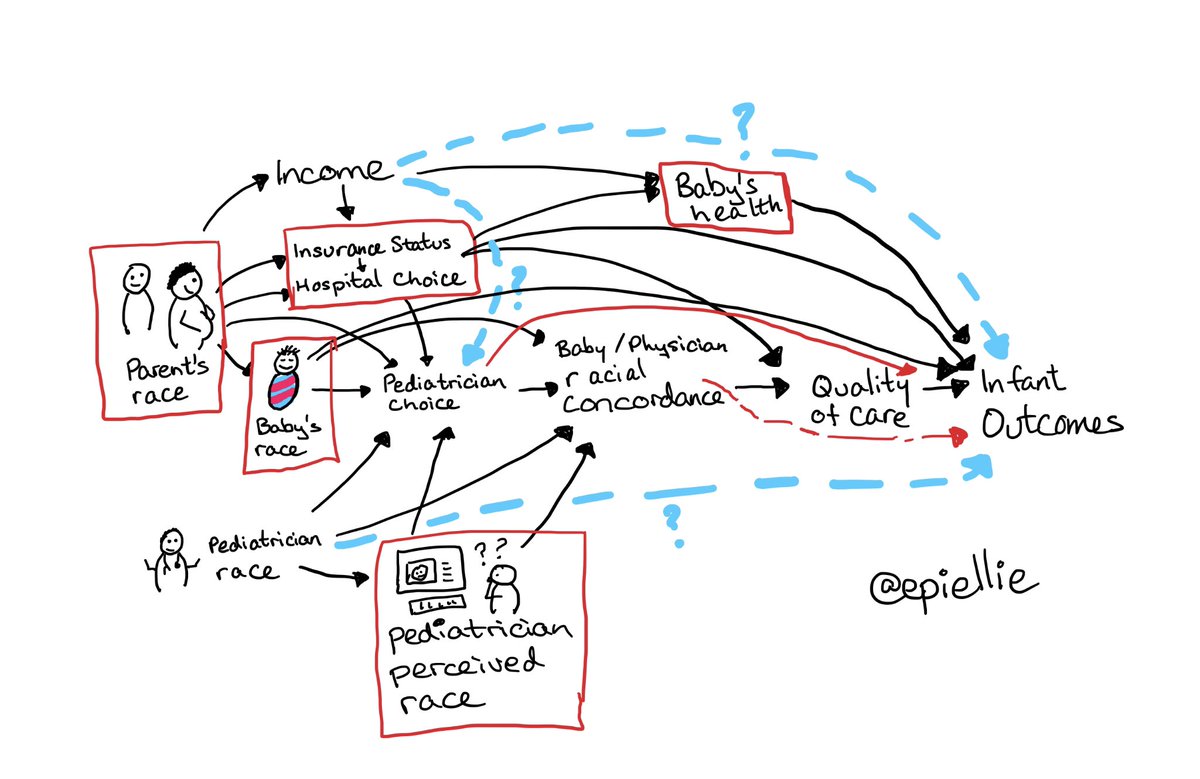

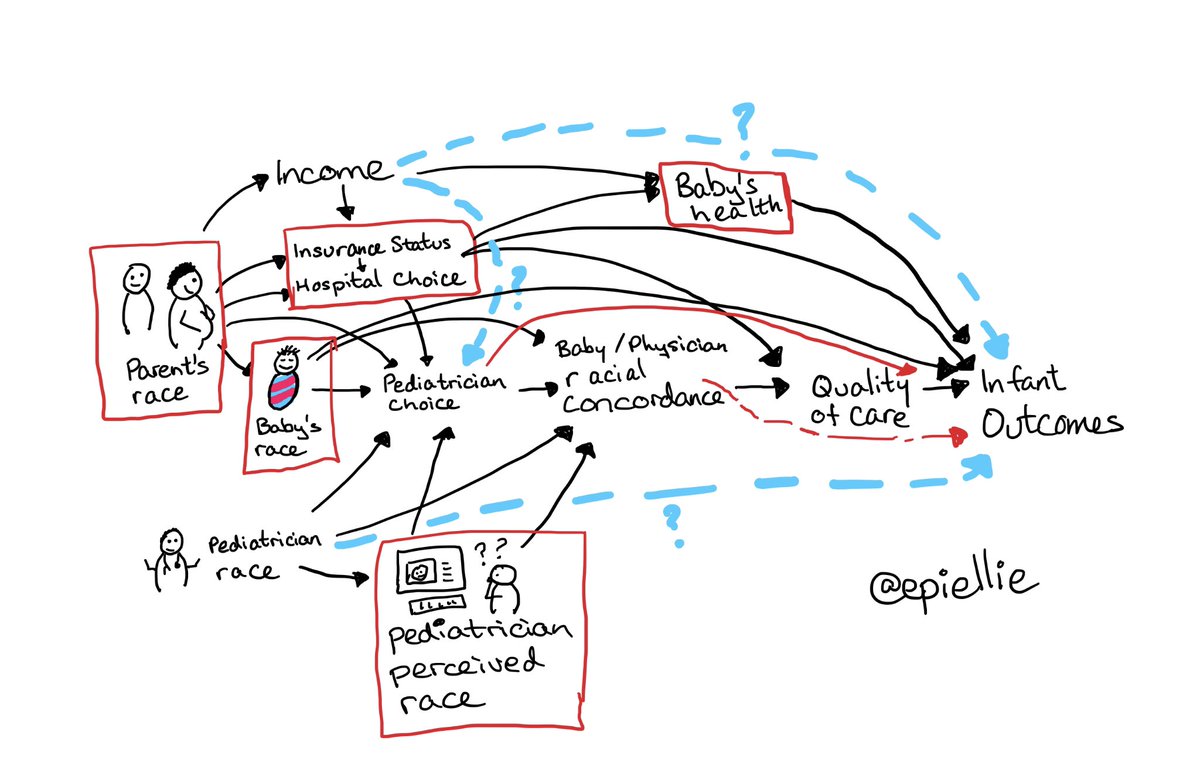

After reading the paper & the criticisms here’s my attempt at understanding the relationships at play.

The main question is whether racial concordance modifies or mediates (we don’t care which so my graph allows both) the effect of baby’s race on baby’s outcomes—the red arrow.

The main question is whether racial concordance modifies or mediates (we don’t care which so my graph allows both) the effect of baby’s race on baby’s outcomes—the red arrow.

In this causal diagram, black arrows are potential causal relationships, red boxed are analytic adjustments, the red dashed pathway is the one we want to know about, and the blue dashed arrows are potential unknowns.

So, what does this tell us?

If none of the blue relationships exist, then the analysis *can* tell us about whether matching baby & pediatrician race improves survival for Black babies.

If none of the blue relationships exist, then the analysis *can* tell us about whether matching baby & pediatrician race improves survival for Black babies.

So why do other people disagree with me? Let’s walk through some of their objections.

The researchers used “perceived pediatrician race” instead of “pediatrician race”. This means potential misclassification.

Is this a problem? Only if pediatrician race causes infant outcomes *unrelated* to a pediatrician’s perceived race!

Is this a problem? Only if pediatrician race causes infant outcomes *unrelated* to a pediatrician’s perceived race!

That is, it’s only a problem that we have perceived race instead of actual race if the blue dashed arrow at the bottom of this picture exists.

I believe it doesn’t.

I believe it doesn’t.

What about the fact that parents may choose a pediatrician based on that pediatrician’s (perceived) race? Is that a problem?

Probably not. Why? Because the main reasons for pediatrician choice (other than race) are likely insurance & hospital & these are controlled analytically.

Probably not. Why? Because the main reasons for pediatrician choice (other than race) are likely insurance & hospital & these are controlled analytically.

One other possible cause of pediatrician choice might be income, and if that is true *and* UNRELATED to insurance or hospital (ie no top left blue line) then there *might* be a problem here...

EXCEPT income is still only a problem if it’s an *independent* cause of survival

EXCEPT income is still only a problem if it’s an *independent* cause of survival

Although income does predicts infant outcomes, it most likely isn’t a *cause*.

Instead, income probably tells us about baby’s health, insurance, hospitals, & doctor. The top right-most blue line likely doesn’t exist.

These are controlled for.

Instead, income probably tells us about baby’s health, insurance, hospitals, & doctor. The top right-most blue line likely doesn’t exist.

These are controlled for.

There’s one last possibility. Choosing a pediatrician might be directly relates to infant outcomes, regardless of anyone’s race (solid red line).

If that’s true, then the findings of this paper could still be right BUT what we do next should change.

If that’s true, then the findings of this paper could still be right BUT what we do next should change.

Interpreted as the authors did, the study results suggest minimizing death by ensuring babies have racially concordant pediatricians.

If *choice* is the main cause, then we need to give parents of Black infants the *option* to choose a racially concordant pediatrician.

If *choice* is the main cause, then we need to give parents of Black infants the *option* to choose a racially concordant pediatrician.

That’s different, sure, but not *so* different that it undermines the study or the authors conclusions. Both imply the need for more Black pediatricians AND more access to Black pediatricians for parents of Black infants.

I’m running out of  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">, so I’m going to close here by encouraging you to read this paper and think deeply about it’s results.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">, so I’m going to close here by encouraging you to read this paper and think deeply about it’s results.

And then, just like @RRHDr & colleagues, think creatively about how to ask causal questions that move us towards interventions that reduce disparities!

And then, just like @RRHDr & colleagues, think creatively about how to ask causal questions that move us towards interventions that reduce disparities!

Another objection that people have been putting forth: the doctor listed on the paperwork is not the one treating the babies. Does that introduce bias? Not necessarily. But now the interpretation is: when Black babies have a Black physician listed they are more likely to survive.

Does that mean exactly the same thing as the original interpretation? No. Does it mean Black babies dont need a Black doctor on their care team? Also no. The interpretation might be different, but the solution is the same: more Black doctors for Black babies.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter