After 12 years of military rule, Peru held presidential elections on May 18, 1980. Months before, a national assembly had promulgated a progressive Constitution. Ousted in 1968, Fernando Belaúnde regains the presidency. The night before elections, in Chuschi, a revolution began.

Gustavo Gorriti’s early account explains the peculiarity of Chuschi. A prosperous and stable community in Ayacucho, it had been subject to derailed projects of modernization. Sendero attacked the electoral post, burning boxing ballots, expecting a wide polarizing effect.

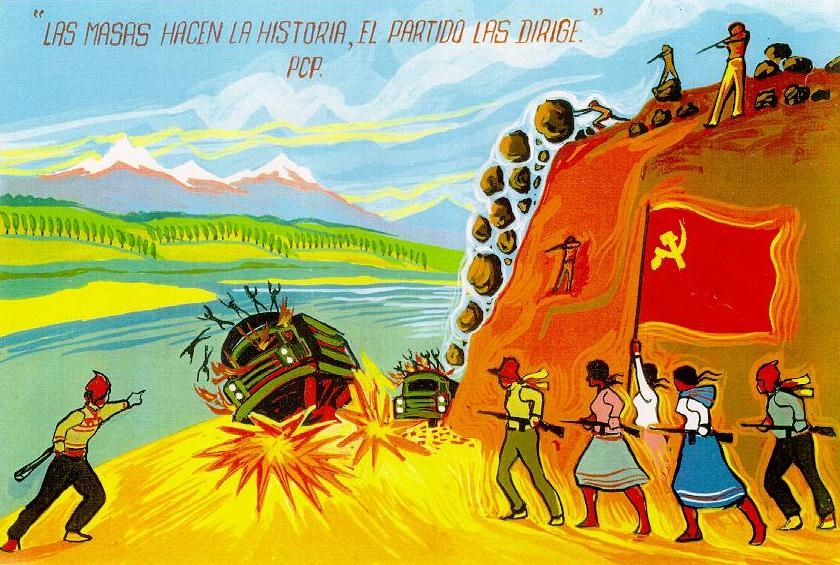

As C.I. Degregori reminded us, Sendero Luminoso was one among many leftist parties that claimed the need for an armed struggle. Three features distinguished them: the role of the San Cristóbal University, the personality of its leader Abimael Guzmán, and its Maoist orientation.

Peruvian Maoism emerged in the midst of a global Sino-Soviet split in 1964. Geneviéve Dorais has reconstructed the genealogy of Maoist parties. Unlike Marxism-Leninism, Maoism "made sense" of Peruvian rurality. Endless atomization led Sendero Luminoso to surface in 1973.

After the Chuschi attack, Sendero Luminoso continued its sabotage campaign against state infrastructure and symbolic places, including General Velasco’s tomb. @Miguel_La_Serna has also documented the early proselytizing campaign and support among conflicted campesino communities.

By December 1982, violence had escalated. President Belaúnde dispatched armed forces to Ayacucho. A month later, 8 journalists are massacred in Uchuraccay. Ponciano del Pino offered a reflection on the role of this massacre and the subsequent investigation led by M. Vargas Llosa.

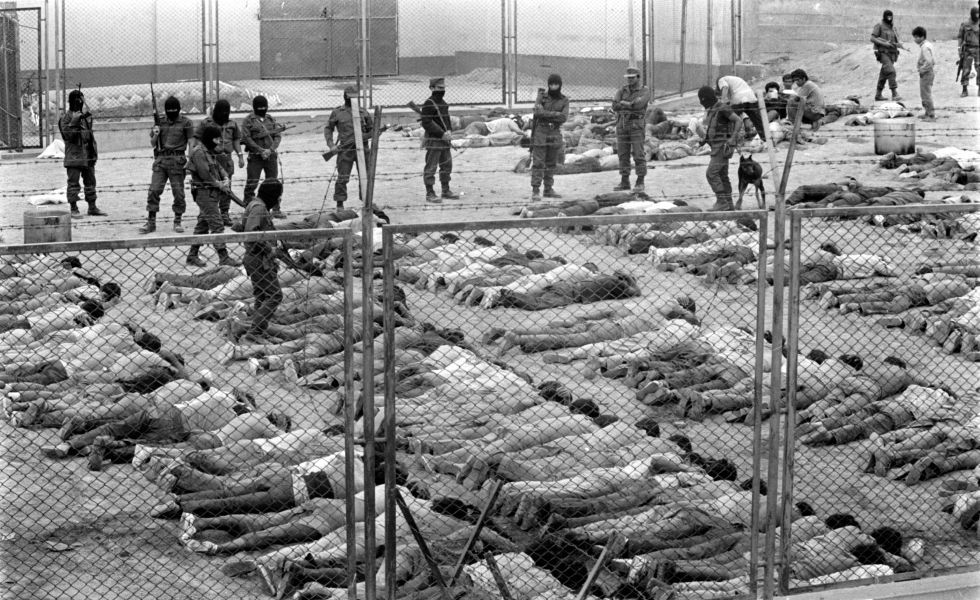

Despite military interventions, violence ensued. Under the presidency of Alan García, the state unleashed an indiscriminate campaign of counter-subversion. In June 1986, the Navy committed the Massacre of the Penales, assassinating 300 inmates in 3 prisons. Crisis became total.

By 1989, in the words of @jomaburt, the conflict had become “terror versus terror.” Sendero Luminoso advanced over the urban periphery of Lima, attempting to reach their “strategic equilibrium” while massacring grassroots leaders. Paramilitary groups riddled the same communities.

Extreme crisis triggered civil society resistance. Campesino militias, urban grassroots leaders, and special police groups confronted Sendero Luminoso. On September 12, 1992, GEIN captured Abimael Guzmán in Lima. Still, state terror ensued. Counter-subversion without subversion.

Despite the impact of the conflict, Peruvians remained unaware of the extent of insurrectionary and state violence. In 2001, a transitional government established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission - CVR. @PriscillaHayner placed the CVR among the five strongest TCs in history.

The CVR released its final report, Informe Final, in 2003. More than 15K testimonials gathered in decentralized public audiences, led to the making of nine volumes that documented an age of atrocities. Among its conclusions, the notorious figure of 69,280 casualties stands out.

The mathematics of death. Of those 69,280 Peruvians killed during an Internal Armed Conflict, 79% lived in rural areas, 56% had an agrarian livelihood, 68% had a scarce formal education, 75% spoke Quechua or another indigenous language, 85% lived below the poverty line.

The term Internal Armed Conflict (IAC) is subject of heated public debate. The right neglects its value and advocate for the term “terrorism,” validating all human rights violations perpetrated by the state. Elizabeth Salmón explains the analytical and legal value of the IAC.

In an effort to institutionalize the collective memory of the IAC, the Peruvian state uncomfortably completed the construction of the @LUMoficial in 2015. LUM has been subject of attacks from right wingers, particularly the Fujimorismo. The current director is @BurgaDia1.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter