Here’s a shot-by-shot analysis of my favorite movie, Late Spring, which will probably end about ten minutes into the movie.

The film opens with an establishing shot of the train station near Noriko& #39;s house, which she will use later in the film with her father. Kamakura is also where Ozu is buried, and where Setsuko Hara lived after she resigned from public life.

Ozu stays at the train station for his second establishing shot, though he again avoids trains themselves - the only movement in the film so far is from trees in the breeze.

The final shot at the train station in this sequence appears to be back on the stairs from the first shot, albeit from a different angle to center the train signal.

The final person-free establishing shot is of the top of Kenchoji, the oldest zen temple in Japan, a clear introduction of the theme of tradition for Japanese audiences. It& #39;s also where the tea ceremony in the first scene will take place.

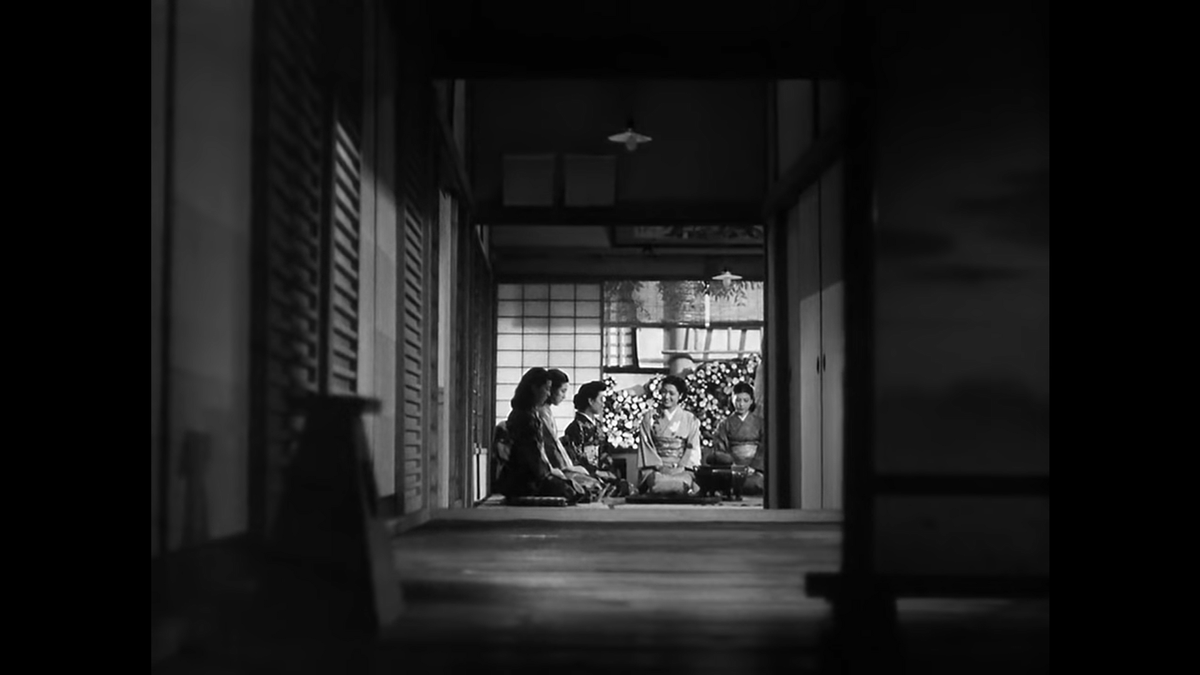

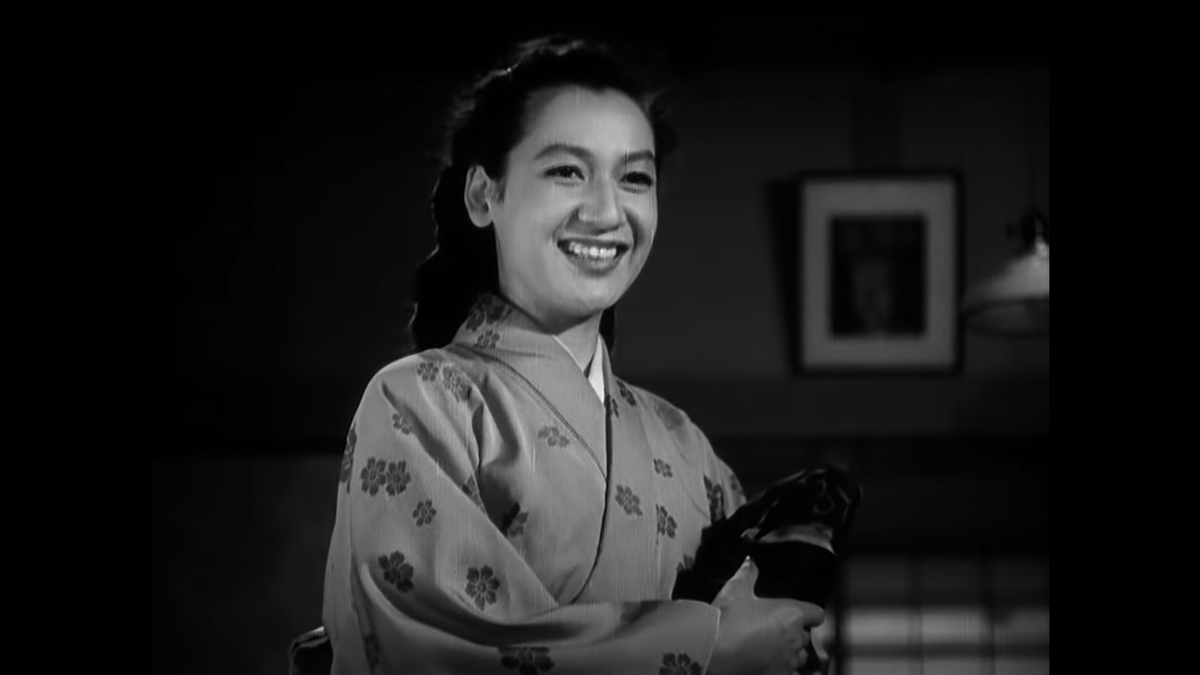

Our first shot with people is down a hallway; we can see a group of women in kimonos before another woman arrives and bows. This is our star and protagonist, Setsuko Hara as Noriko. Note the characteristic low angle and geometric structure of the composition.

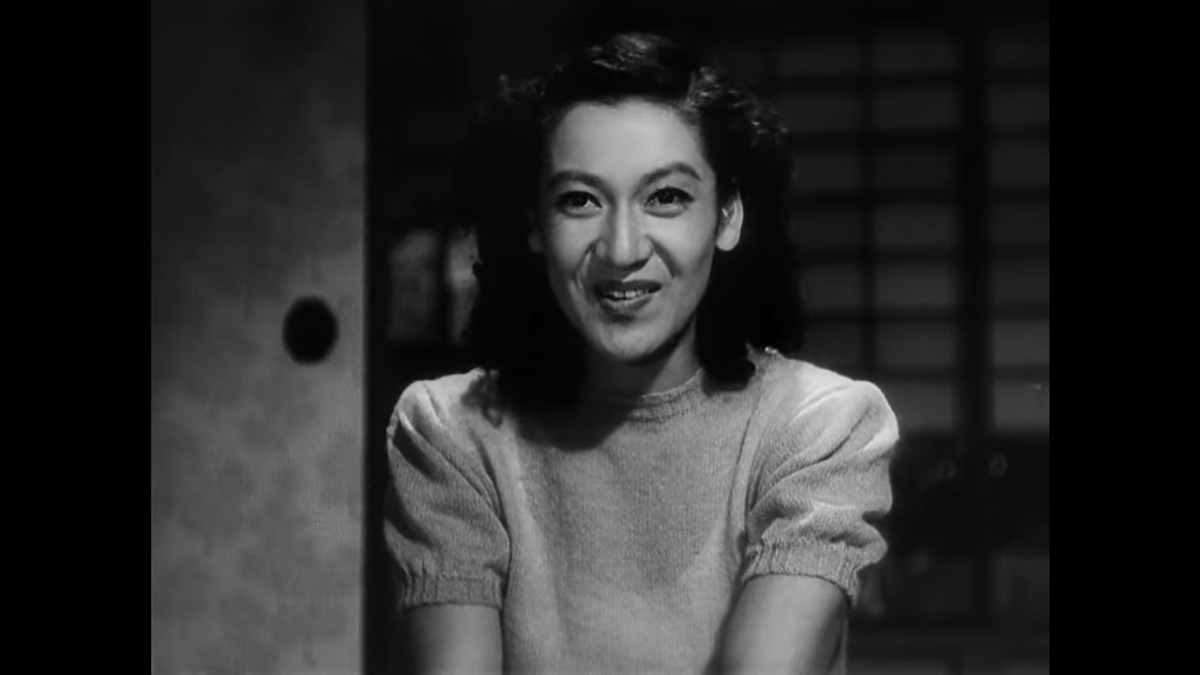

Here we get our first head-on look at Noriko, and while it’s not the full 180° flip Ozu is most famous for, it’s still what conventional thinking would view as a disorienting cut; without Noriko’s bow, it would be hard to know this is the same character we saw from behind.

It turns out the last shot was an insert – from the opposite side of the plane, which should be disorienting but again doesn’t register as such – and we are back in the hallway in the continuation of the earlier shot.

Noriko takes her place next to her aunt, played by the iconic Haruko Sugimura. I’ll have more to say about her but the important detail here (which Noriko tried to hide as she arrived) is the handbag, which sticks out as a modern sore thumb in this traditional setting.

This begins a three-shot back-and-forth conversation sequence. Ozu is “famous” for head-on conversation shots, but in this era especially he spent more time in the usual slightly-off-center pocket.

Aunt Masa wastes little time in pawning off a tailoring job to Noriko; some pants for her husband. Later in the exchange she tells Noriko to "reinforce the seat;" Ozu loves butt jokes.

Conveniently, the pants happen to be right here, already wrapped for Noriko.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">

We cut back to the establishing shot again here, this time to welcome Kuniko Miyake, another actress who looms large in Japanese cinema, here playing Mrs. Miwa, a key character in the unfolding narrative.

The arrival of her character is noted with the same shot sequence as when Noriko arrived at the ceremony; this is a character that threatens to take Noriko’s place later in the film, so this repeated sequence is an omen.

Aunt Masa throws a bit of shade Mrs. Miya’s way about being late. Note Noriko’s melancholic look as she notes Mrs. Miya; one of her greatest mysteries in the movie is a feeling that she always knows more than the audience about where this is headed.

One last shot of Mrs. Miya saying she missed her train. Few actresses in history had a kinder face than Kuniko Miyake. Who’d be threatened by this lady?

The assistant arrives in a frontal shot with Noriko centered. Notice the five planes here: two shoulders and a cup in the extreme foreground; the tea kettle and cups; Noriko and her aunt; the assistant bowing; and the shoji (sliding doors with paper windows) in the background.

A sharp cut as Ozu takes us outside. If the first “still-life” compositions were establishing shots, here then are the film’s first “pillow shots,” which serve as a transition from the modern pleasantries of the first half of the scene to the formal tradition of the tea ceremony.

The idea of pillow shots in Ozu’s films seems ubiquitous to us, but it’s actually a Western concept. The term was first coined by Noël Burch, who adapted it from the concept of pillow words in Japanese waka poetry.

Here’s a beautiful composition, using the post to divide the frame into thirds that are complemented by the two prominent shrubs and the out of focus leaves in the foreground.

Another careful composition. Note the vase in the far corner that fills out the empty space in the background, and again we have shoulders in the extreme foreground to provide another plane. Despite the sharp angle Ozu’s 50mm lens still gives the impression this is a flat image.

Noriko shown from the same extreme angle. What’s she thinking here? Hara is a master of melancholic ambiguity. And is that Aunt Masa on the other side from where she was before?? Ozu you sneaky bastard.

Ozu spends quite a bit of time on the tea making; to cut from this moment at any point would be counter-intuitive considering the process and its careful use of time is precisely the point. Note the awesome ladle and matcha whisk – tea making is fun!

A close up of Mrs. Miwa here. Miyake was just 33 when she made this film, only four years older than Hara.

We are back outside, this time from the opposite side – note the sandals, which were in the first pillow shot outside the temple. The shot also includes the plants from the second pillow shot and the post from the third.

We’re moving away here, transitioning to a different space. There’s no sign of where we are going, and shots like this make the best case for a characterization of Ozu’s still-lifes as punctuation markers.

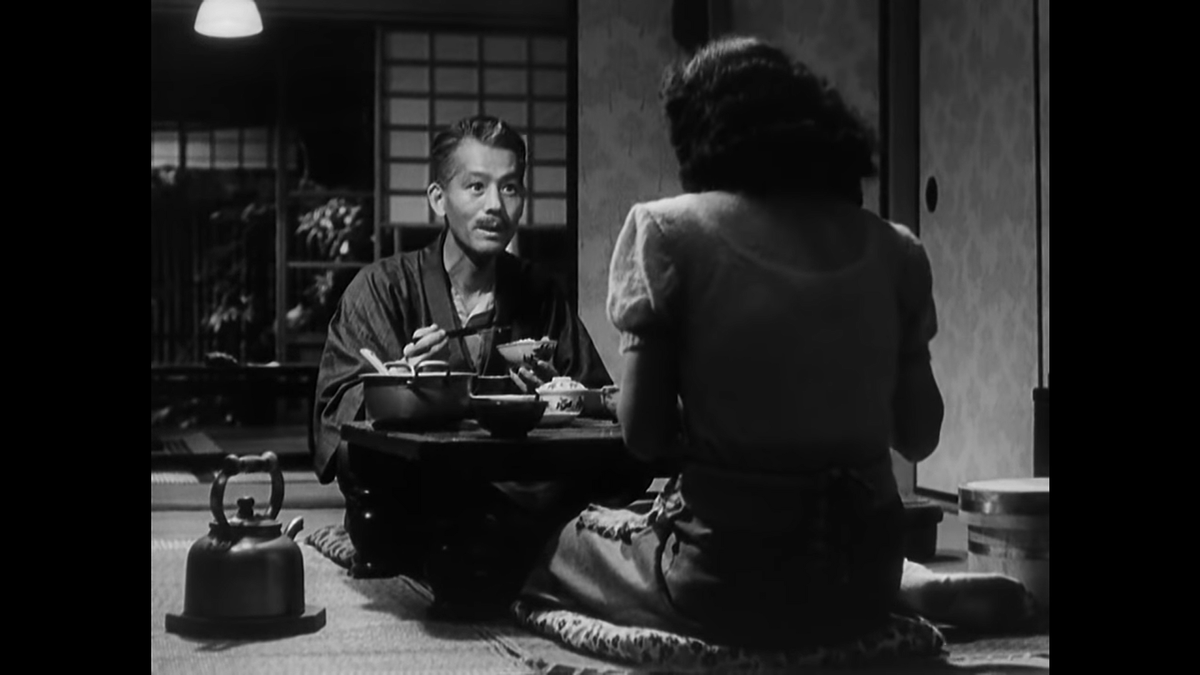

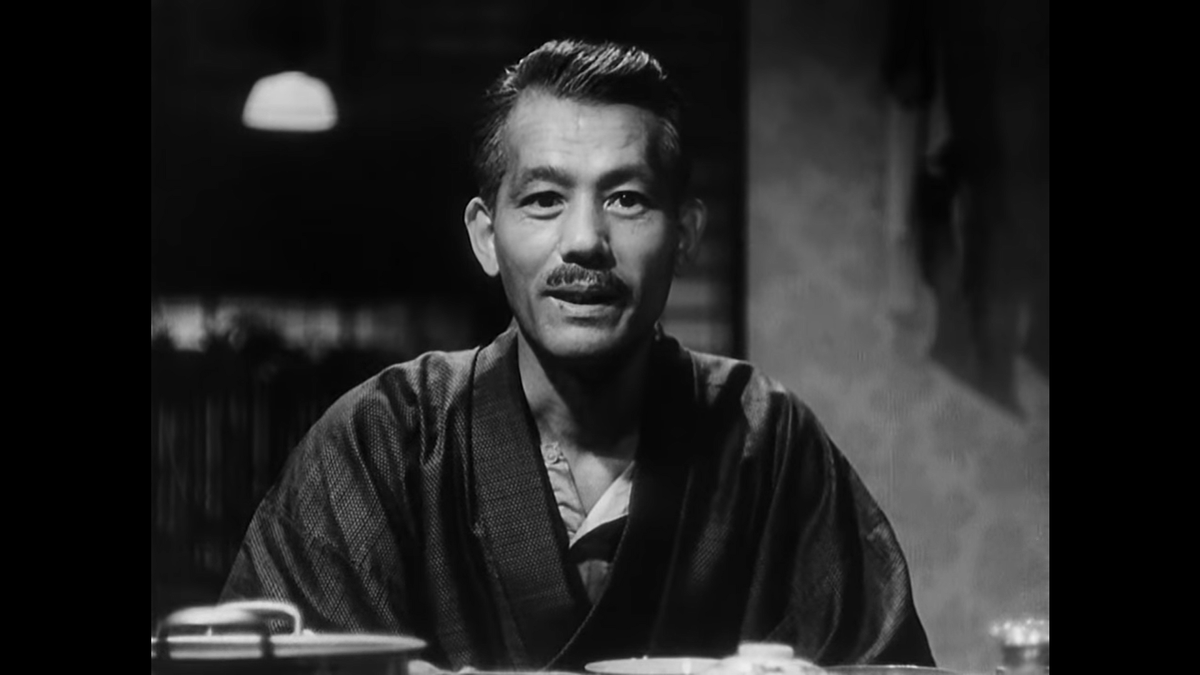

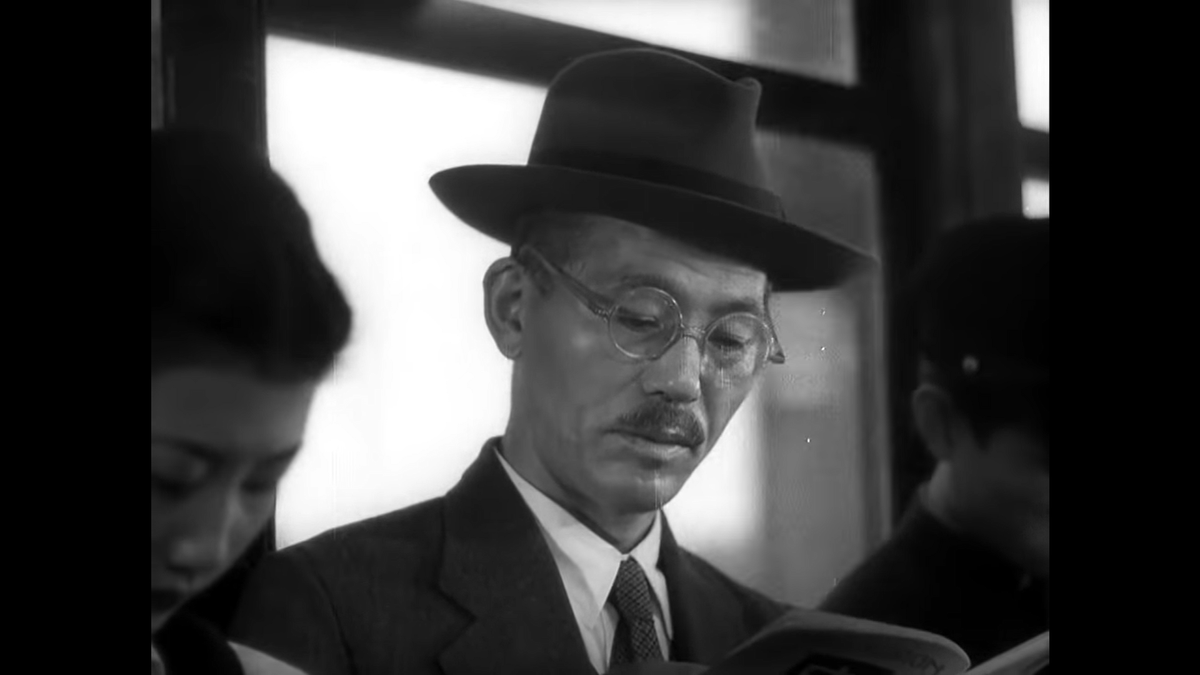

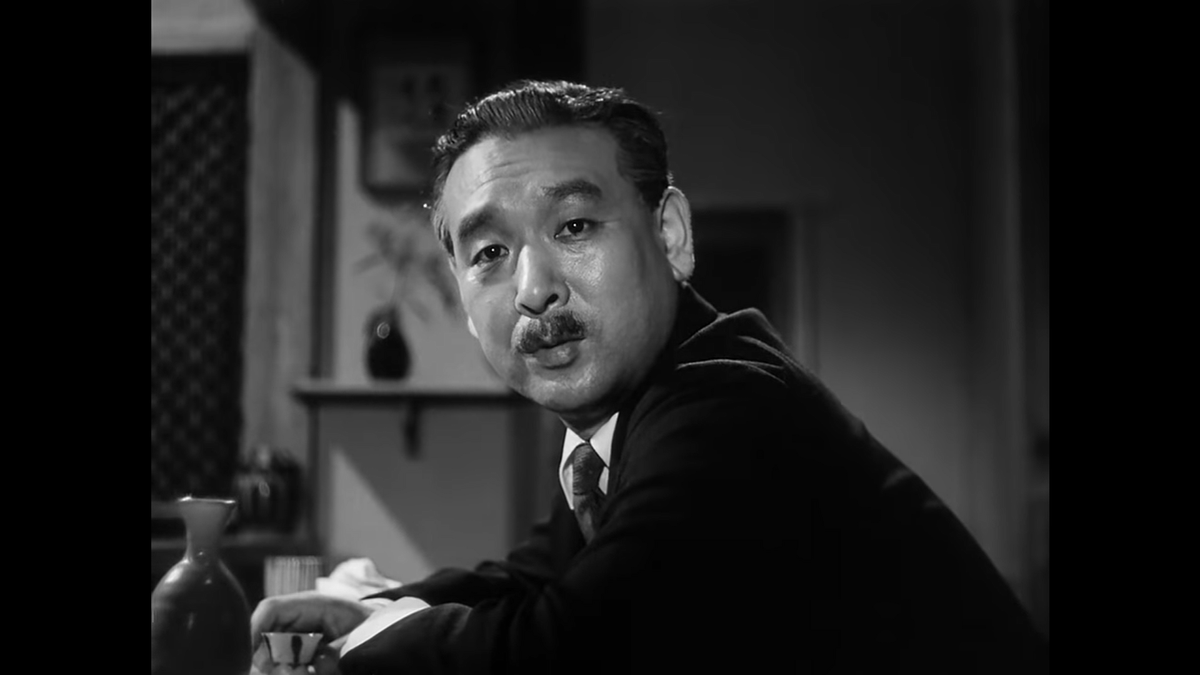

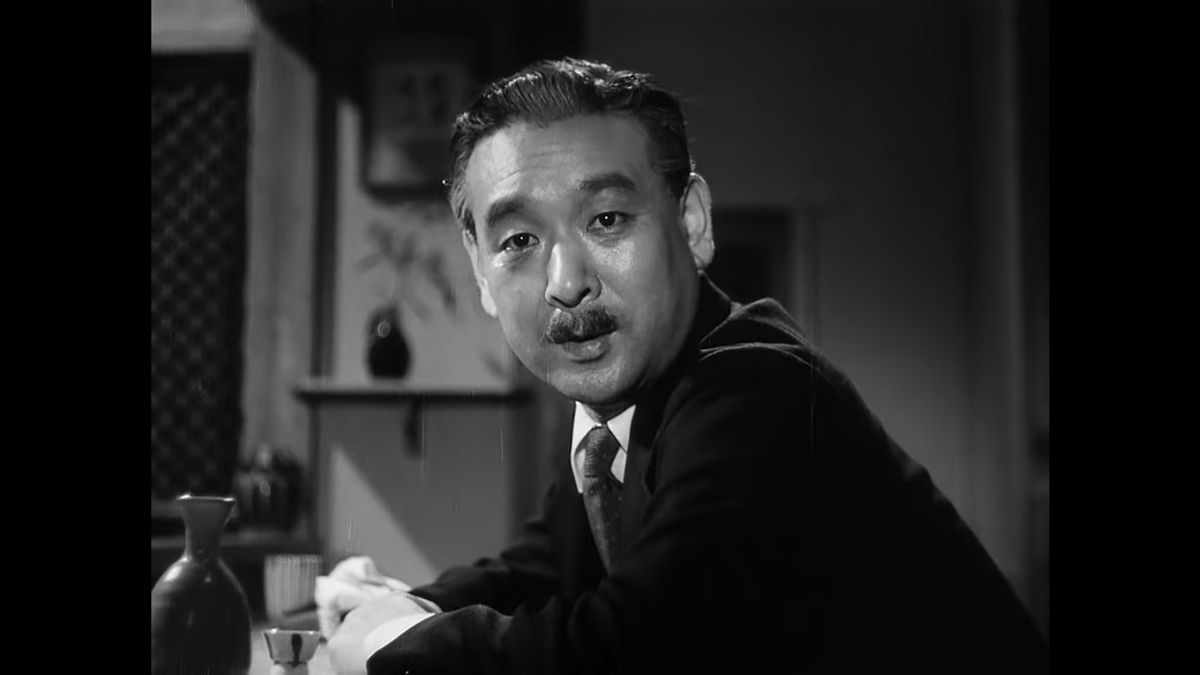

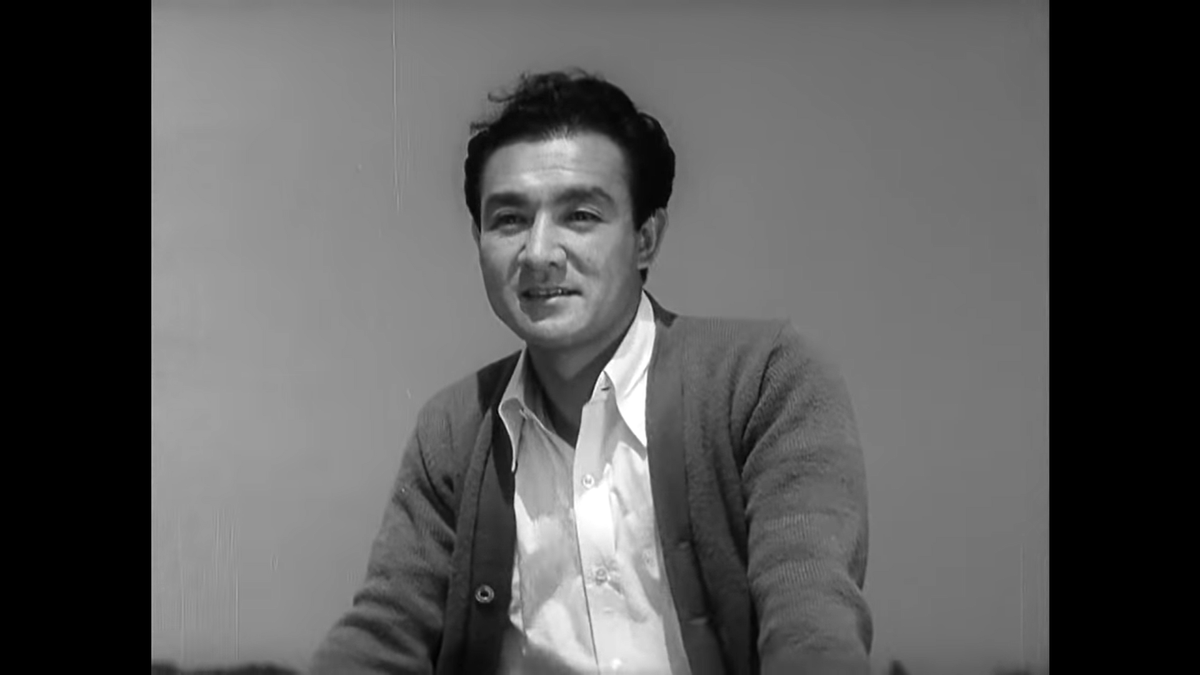

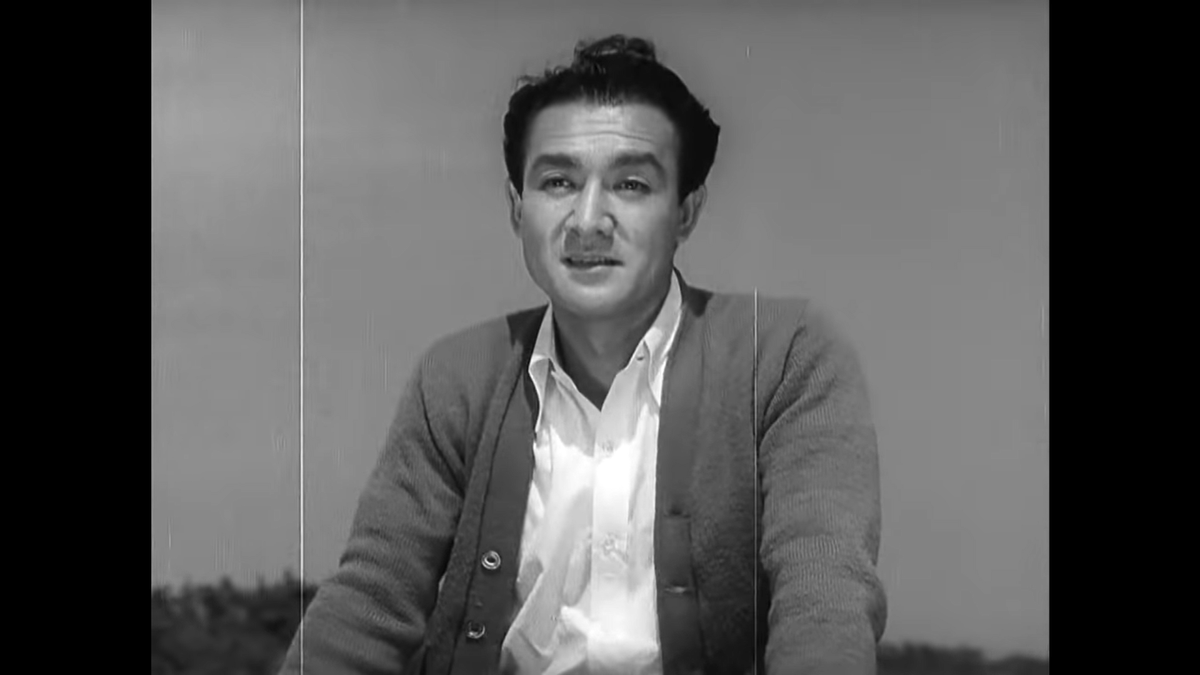

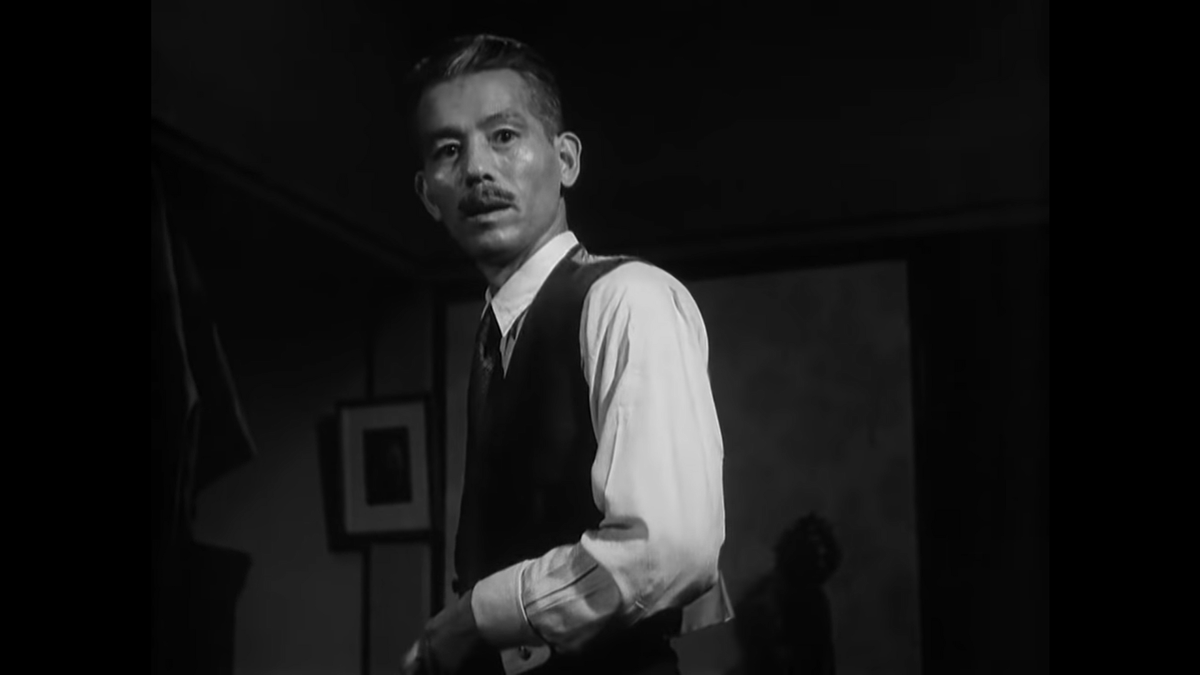

Here is our first shot of Chishū Ryū as Shukichi, Noriko’s father, here sitting next to Jun Usami. This is also our first look at the home he shares with Noriko. Note we meet Noriko in a traditional setting while Shukichi is introduced studying European economics.

This is the first true POV shot, yet it’s pretty clear in this shot-reverse shot sequence that they never actually look at each other in the exchange.

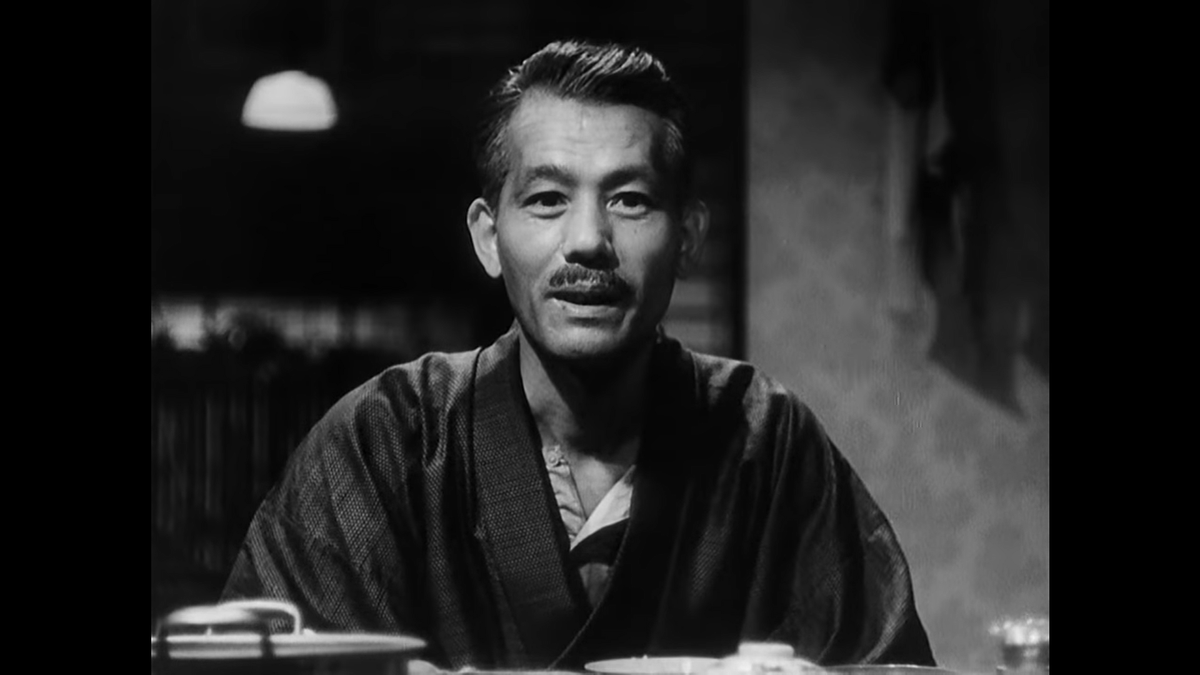

Chishū Ryū was 45 when he made Late Spring, which would mean his character had Noriko at 19 if he was playing his actual age. However, I think they made him appear older here than in real life – though not as much as in Tokyo Story a few years later.

Here’s another near 180° flip and we get our first look at the layout of their main living space. This sequence has now had four shots: a long shot facing to the left, a medium shot facing to the right, a medium shot facing to the left, and now a long shot facing to the right!

Another view of the house, this time down a hallway that is placed behind the first shot’s camera placement as a repairman arrives. The perfect symmetry is key here, which is accomplished through the low angle and flat composition.

Compare this repeat shot to the flipside shot two cuts earlier and it’s clear that Usami has been moved. Here he is closer to the wall they are both facing, but in the reverse shot he is further back. This is characteristic of Ozu, who valued aesthetic appeal over continuity.

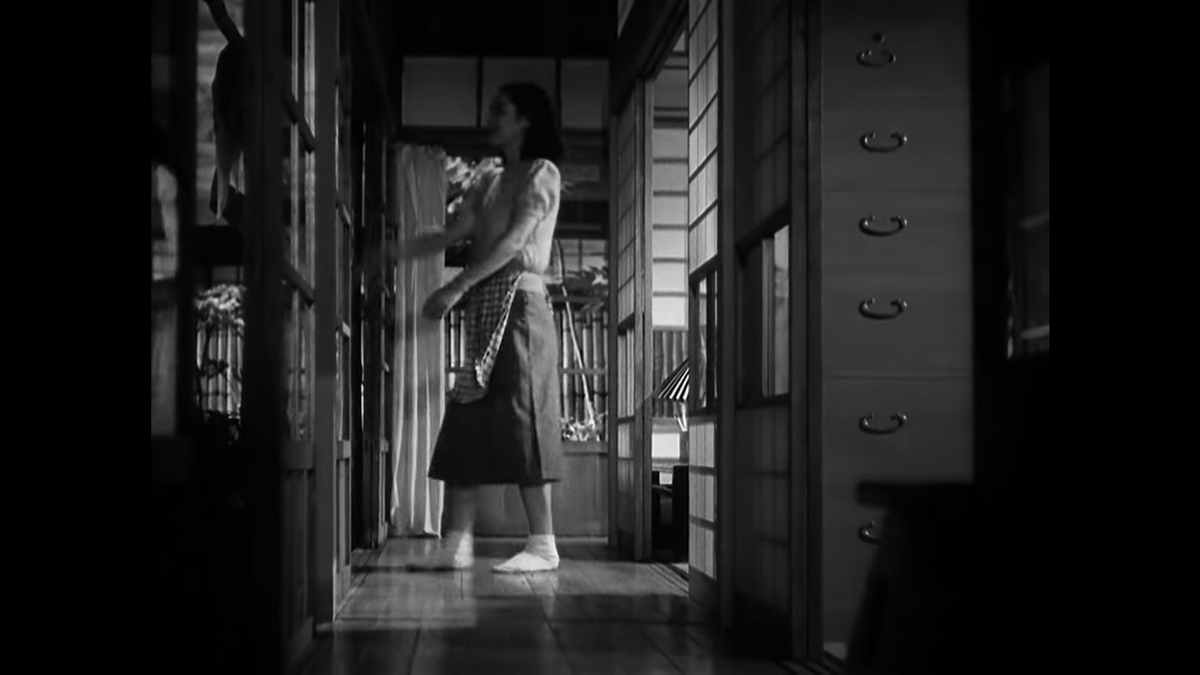

This is our first look at one of the most significant angles in the film. We come back to this exact same shooting spot at key moments throughout the movie. Here, Noriko is chilling like it ain’t no thang.

Here she is entering their house, another shot that will be repeated (albeit with less narrative weight). If you aren’t a fan of frames look away! I’m not even sure what’s going on with the console table.

This shot has moved over slightly to the left to accommodate Noriko as she enters from the right and moves into place for a nice linear composition.

Here’s a head-on angle on someone speaking, the stereotypical Ozu approach, but the speaker isn’t facing into the camera. Usami as Shôichi is wearing a Western suit, in contrast to Ryū’s traditional garb.

This exchange is the first hint of a potential romantic relationship between Noriko and Shôichi. It also establishes the idea that Noriko has some sort of health issue, to the point where she has to visit the hospital.

We also learn that not only does Noriko help her father around the house, she also transcribes his writing.

Shukichi spends a lot of time putting on and taking off his glasses in the movie; it’s sort of a signature move.

Here’s a direct look at the camera in conversation. The previous medium shot of Shôichi, which was from the front as he turned to speak to Noriko, expanded the sphere of conversation; here, Ozu moves back to a 1-on-1 dialogue.

This section is intended to show Shukichi’s childlike lack of discipline, as Shôichi brings up mahjongg, leading the older man to call for Noriko to set up a game with a neighbor.

Noriko shoots down this idea with a typical “finish your homework, then you can play” mom-style smackdown. This is a slight variation on the shot when Noriko arrived – note the bit of frame we get on the right hand of the screen (also in the first shot from this angle).

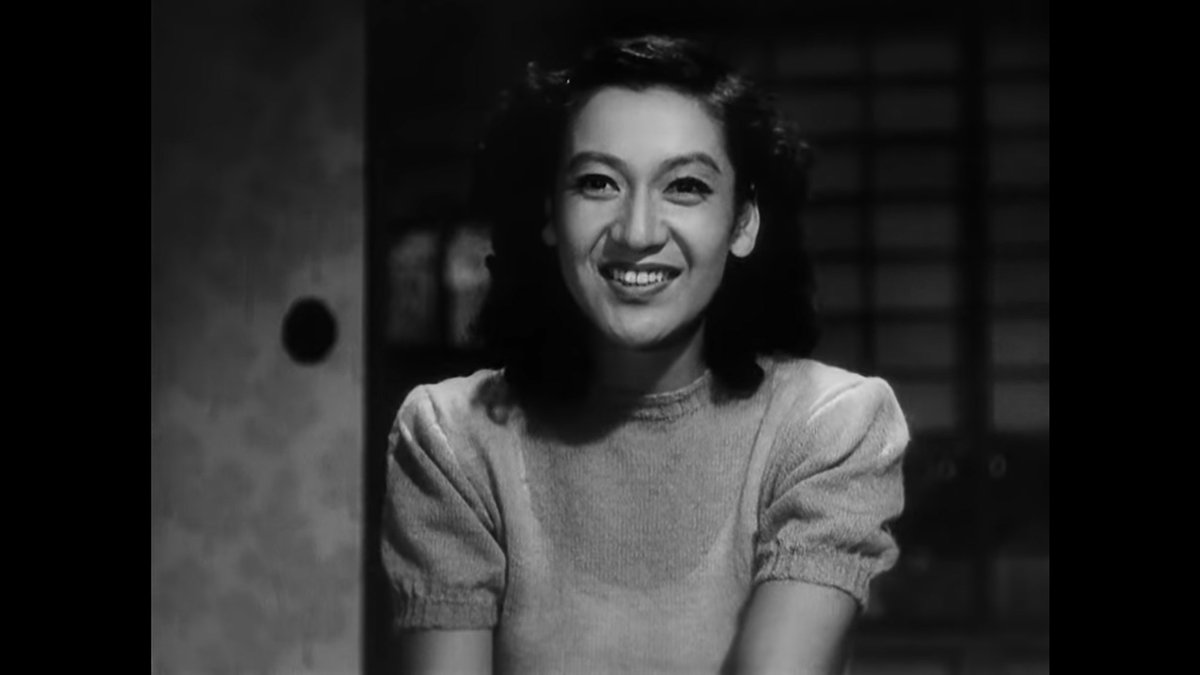

Hara is the actor most cinephiles immediately associate with Ozu, but she actually appeared in just six of his films.

In contrast, Chishū Ryū appeared in 52 of Ozu’s 54 films, with large roles in the vast majority he made after the war.

Although it’s a firm hand, Hara delivers it with a playful self-awareness; she knows she is playing the mom role and leans into it to emphasize the absurdity of keeping her father in line.

Her father does the same; this is a pleasant game they play that they both enjoy. He settles back into work here as we return to the same camera placement, though some of the objects in the frame have shifted slightly (imperceptibly at regular speed).

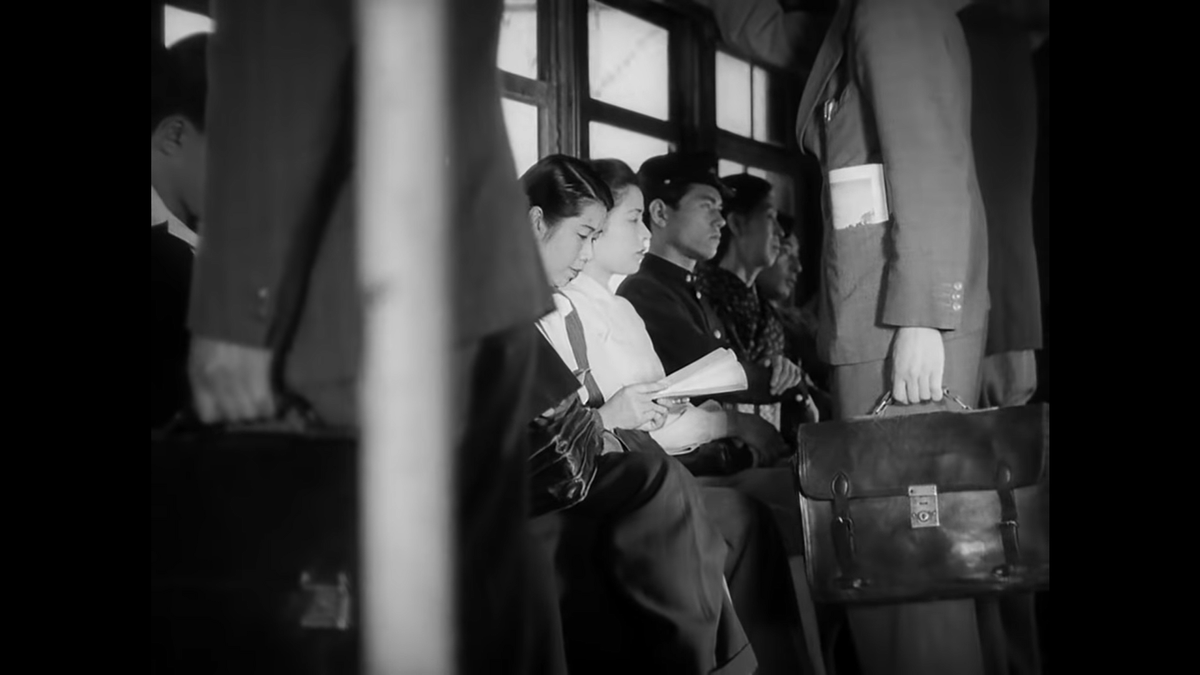

You wouldn’t be weird to assume this is Hara waiting at the train station, but it’s not; this is another transition shot. The next sequence would last about 10 seconds in a typical film; here, it takes Noriko and Shukichi three and a half minutes to get to Tokyo.

The same woman is seen here from the opposite side (with an additional man). There’s a great essay in this Tokyo Story reader about how it’s always a sunny day in an Ozu movie (except when it’s not): https://smile.amazon.com/Ozus-Tokyo-Story-Cambridge-Handbooks/dp/0521484359">https://smile.amazon.com/Ozus-Toky...

Our first actual train! Ozu spends a whole lot of time on this train ride. The dude loved trains, as we’ll see, and we actually get to see the whole train ride past in this shot.

Don’t get too excited but this is the first time the camera moves in this movie. Of course, it’s just moving because it’s on a train; otherwise it’s just a boring old stationary shot!  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">

Almost exactly 30 seconds have passed since we left the Somiya house. We know Noriko planned to take a train the next day, but other than that there’s no frame of reference here. Note again the post separating a third of the picture.

There they are! Noriko is wearing a modern suit with more stylish hair here; she’s ready for a day in the city. Shukichi also has a Western suit on. He asks if she brought the manuscript, providing us with a reason for his presence.

This train shot is characteristically long (relatively speaking) at 15 seconds. We see the whole train go by, but Ozu also holds on the shot until the train is practically out of sight. Note, too, everything going on in this simple train shot! Even some wood in the grass.

There he is, sitting down. Get ready for a clean removal of the glasses as he asks Noriko if she wants to sit down. We are seeing Shukichi from the same angle that we saw Noriko from in the previous shot, so naturally he is sitting behind her, right?

The kicker is that most people watching the movie at regular speed are not going to notice this transgression of the first rule you learn in film school; they just are where they are. Is Ozu investing more or less confidence in his audience in these situations?

Another cutaway to outside the train, with a similar sequence to when we first saw it: a stationary shot as a train rushes by…

…And a shot along the side of the train. Love the sleeve in the breeze in this one, not to mention the pleasing geometry of the railing.

Wait a second – we’re on the other side of our characters here! Again, Ozu just doesn’t care. Composition within each individual shot matters, but from shot to shot continuity only goes so far.

Here’s our first look at any indication of what Japan is going through at this point in history. Scaffolding and bombed-out wreckage along the side of the railway tracks indicates that we are getting closer to Tokyo, which took significant damage in WWII.

Noriko and Shukichi say goodbye here as they go their separate ways. The film establishes the ease and gentle pleasure of their relationship in these opening scenes in such a, well, easy and gently pleasurable way.

We can finally see Tokyo in the distance here as we transition out of the train sequence with a series of pillow shots.

How about the window in this shot? There’s no reason for it to be there other than Ozu’s focus on a pleasing composition, particularly as it pertains to depth of field and divisions of the frame.

We’re finally in Tokyo and we’re rewarded with this nice side shot of a beautiful building. This is not a random choice: this is the Hattori building which played a major role in the US occupation of Japan: it was the home of the film censorship board. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

Here it is again to hammer it home. The US occupation lasted from the end of the war until the early 50s, and throughout that time all films needed to be approved at each stage of its production. These shots represent a MAJOR component of this movie, not just an inside joke.

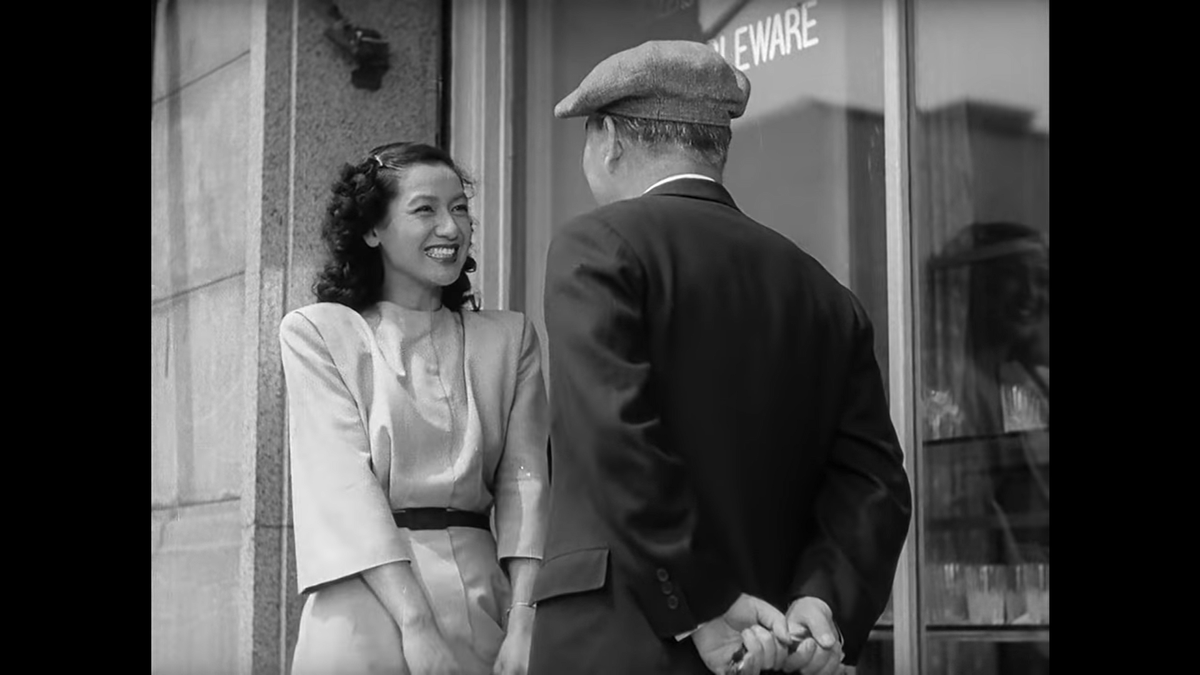

This is a great shot of Noriko from across the street as she sees someone and comes to the foreground. Check out the cocktail shakers in the window. Rather than stop in an unobstructed place Noriko moves over, likely to provide a better set-up for the next shot.

This is a friend of Shukichi named Onodera. He mentions that Noriko has put on weight since he last saw her, another hint at a previous illness (though of course a lot of Japanese people put on weight post-war).

Here’s a reverse shot as they decide where they are headed. One funny thing about this sequence is that Ozu declines to provide Onodera with an introductory insert using a medium shot or close up so we get to know his face. We see him from behind 98% of the time.

Here’s an elliptical sequence that is vintage Ozu: the two decide to attend an art exhibition, which is shown exclusively through placement of two signs. Here, we see the sign Onodera was standing next to in the previous shot.

Then, we see the same sign outside what is ostensibly the art museum where the exhibit is taking place. He flips the angle to make the transition more aesthetically pleasing.

Here, most filmmakers would at the very least show a quick shot of Noriko and Onodera at the exhibit, or perhaps one of the works of art they see. Instead, we are already on to the next thing: a restaurant where the next scene will take place.

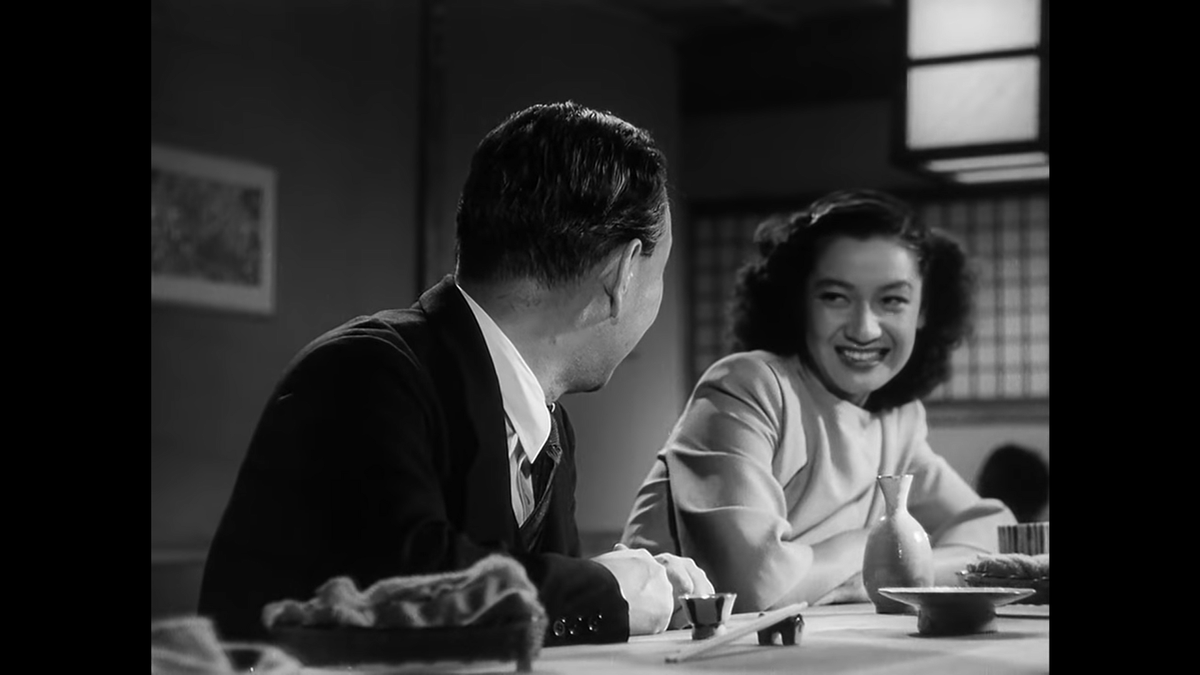

Again Ozu uses his staggered two shot here, and we get our first good look at Onodera. I am a big fan of the shot selection for this sequence – it’s a layout only Ozu would do yet it’s not at all flashy the way most distinctive styles are.

This is as close as we get to an establishing shot in this scene and it’s almost an exact flip from where we were in the last shot, only in a medium long shot rather than a medium two shot. In a way, we have zoomed out from a smaller frame to a larger one.

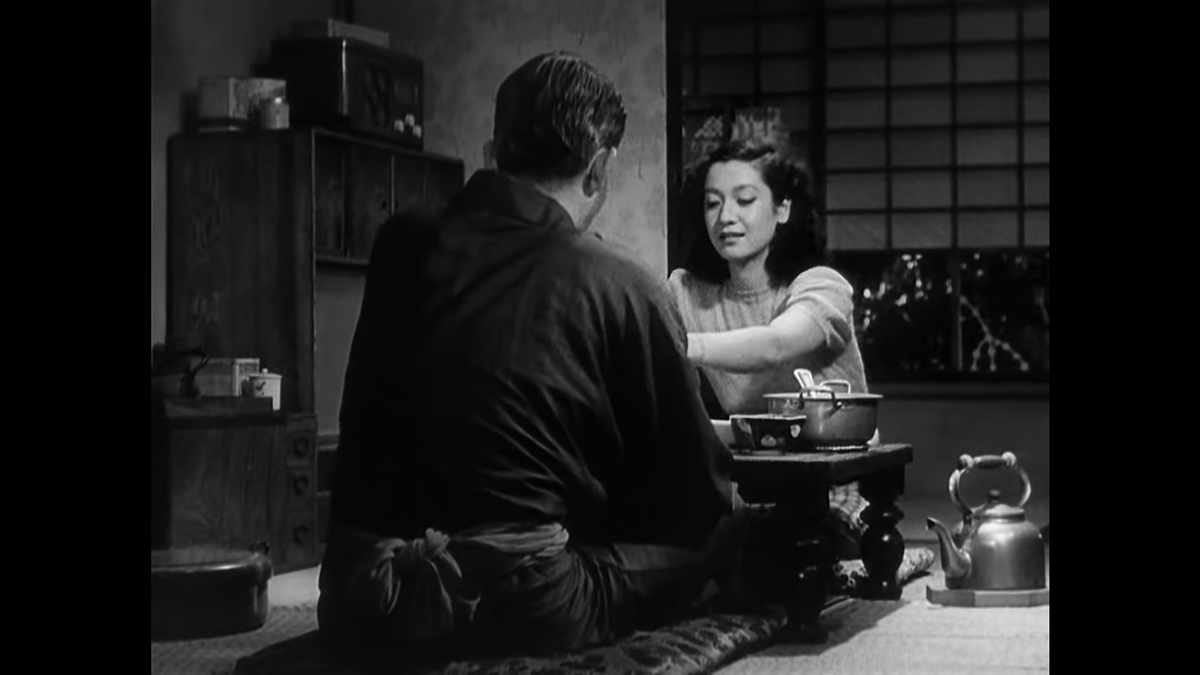

We’re back to the same set up from the other side as Noriko pours sake for Onodera. This is a key scene in that we are privy to Noriko’s feelings about a widower remarrying a younger woman, which are that she frowns upon it.

Here’s another conversation sequence with both characters speaking directly into camera. People have used this method throughout film history, but it& #39;s rare and it’s still largely frowned upon. Ozu is the only "titan" of cinema to use it regularly (afaik).

Hara is especially focused on how Onodera’s daughter feels in the situation. Onodera takes her gently delivered but fairly damning characterization of him as “dirty” in stride.

Hara’s real good in this scene; although it’s her first film with Ozu she had been acting in film since 1937.

She was actually under contract with Toho for the vast majority of her career and was already a star when Ozu and Shochiku borrowed her to make this film.

Think about the unusual construction here: medium two shot that serves as our home base; a long shot from the exact opposite side with more of the room and a third character; plus two shots of people looking directly into the camera. Then out with a hard cut.

Our first night shot as we transition from the restaurant back to the Somiya house, where Shukichi is back at his desk reading the paper.

Noriko has brought Shukichi his gloves, which he had misplaced. This guy would lose his head if Noriko didn’t screw it on for him. This shot is head on across the table from Shukichi, but in between the POV of the two other characters.

Yet this shot is clearly directly from Shukichi& #39;s POV as Noriko looks directly into the camera.

This unexpected encounter of two old male friends is a regular occurrence in Ozu’s later films, here it’s clearly linked to the central conflict of marriage.

Onodera is played by Masao Mishima, who was just 43 here. Mishima appeared in a number of Mikio Naruse films over the decades, and is best known in the west for Masaki Kobayashi’s incredible Harakiri.

This is just about all we are going to get on what Noriko potentially went through during the war. We learn a bit more about her family but this is all we have to go on to figure out exactly what she’s dealing with and how it is affecting her feelings toward marriage.

Onodera’s daughter is also resisting marriage, calling it “life’s graveyard.” Ozu often surrounded his characters with examples of different attitudes and approaches to their central conflict (see the workers in Early Spring), allowing him to fully explore each film’s theme.

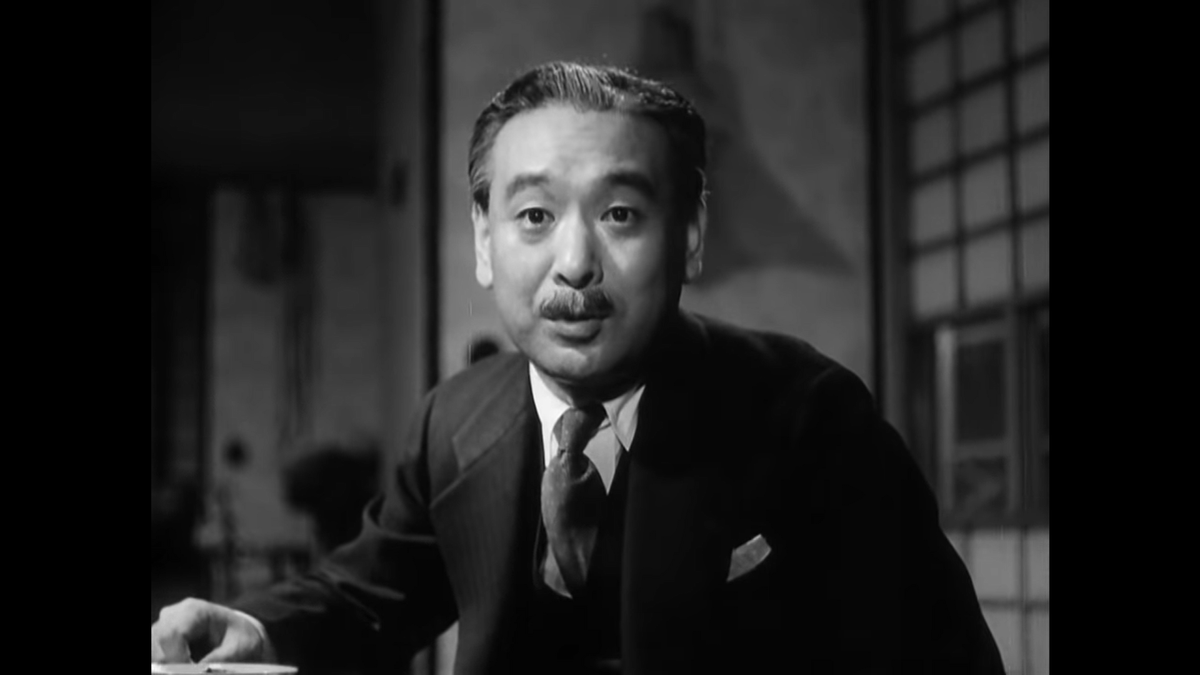

Like Noriko, Onodera looks directly at the camera as he talks to Shukichi. This sets Shukichi up as the central character in the scene, with all three mediums shots essentially directed at him.

Shukichi is clearly not as interested in Noriko getting married as he’s supposed to be (if at all), despite Noriko hitting the ripe old age of 27.

Noriko comes back with the tea, which is only lukewarm. This quick and baggage-free exchange again highlights the ease of their relationship (although a modern viewer might wonder why Shukichi is treating her like a servant).

The success of “serious” approaches to Ozu’s work in the West, like Paul Schrader comparing him to Bresson and Dreyer, has left a perception of the filmmaker as an Artist who Ruminates on the Human Condition, but at heart Ozu is a prankster and satirist.

As these men point this way and that and try to orient themselves in the house, it’s impossible not to wonder if Ozu is winking at an audience he frequently disorients with his own spatial play.

Who& #39;s to say the ocean is this way or that way when all you have to do is change the direction someone is walking toward it as you cut to a totally different place?

And on cue, Ozu flips the orientation of the scene, showing us the conversation from the opposite angle of the establishing shot we have become accustomed to in the rest of the exchange.

Hey we& #39;ve hit 20 minutes! Hope everyone is enjoying.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😀" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😀" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">

Our first look at the ocean is a link between the two men asking about its location and the following scene. We’re going to see a similar shot later!  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😉" title="Zwinkerndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Zwinkerndes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😉" title="Zwinkerndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Zwinkerndes Gesicht">

Here& #39;s a shot that appears to be from the back of a truck; this shot is better seen in motion as Ozu keeps the island in the distance in the same position on the screen as the camera moves along the beach.

This is one of the most iconic scenes in the film as Hara rides a bicycle to the beach, hair blowing in the wind. The previous shot was now clearly intended as a POV shot from her bicycle.

And now we see that Shôichi is riding alongside her. This is a good time to wonder about this particular character and storyline. To begin, I’ll note that Shôichi’s last name is Hattori – the same name as the building in Tokyo where the Occupation was centered.

Surely this must be intentional, right? If Shôichi is a stand-in for the imposition of Western culture what did Ozu mean by including this anti-romance subplot, which seems both to the audience and Shukichi like it will bear fruit?

I generally reject any strong reading of Ozu’s work as a powerful argument in either direction. The filmmaker’s key concern was presenting life as realistically as possible, thereby revealing the futility of such an endeavor.

Noriko’s flirtation with Shôichi, then, can still represent Japan’s relationship with the U.S. at this moment in history, while the ultimate outcome of their relationship isn’t meant to stand in for what Ozu thinks Japan is doing or should do.

The parallels between Noriko and Hattori and Japan and the U.S. reflect the tumultuous moment in history, but they are as flawed as any 1:1 representation in cinema, and no different than the central marriage conceit as a stand-in for the changing of the seasons.

Ozu’s central goal, as we approach another iconic reference to American influence, isn’t to drum up sufficient metaphors to make a larger point, but to match the scale of his characters’ drama with that of history, a satisfying combo for his contemporary audience.

It’s now been more than 90 seconds since we’ve been outside without any dialog or context for what we’re doing here. Just a minute and a half of Setsuko Hara biking. I have no problem with this.

Shôichi finally speaks, asking if Noriko is tired, again pointing out that people are concerned that Noriko is still not back to full health.

She’s not tired, she’s having the time of her life! Post-War Japan saw huge growth in the bicycle industry, especially among women, as people began to use them for recreational purposes (and factories again had access to rubber to make the tires).

Here’s a sign in English informing us that the capacity of the bridge is 30 tons. That’s 60,000lbs, a weight only relevant to loaded semis – or military vehicles.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar! Ozu loved graphic design (we’ve already seen some of his own) so maybe he’s just excited to show this iconic example. However, it’s more likely that this very overt nod to American influence is quite intentional.

A lovely composition, using the fence to connect to the rest of the sequence but focusing on both the bikes and their tracks leading out from the foreground.

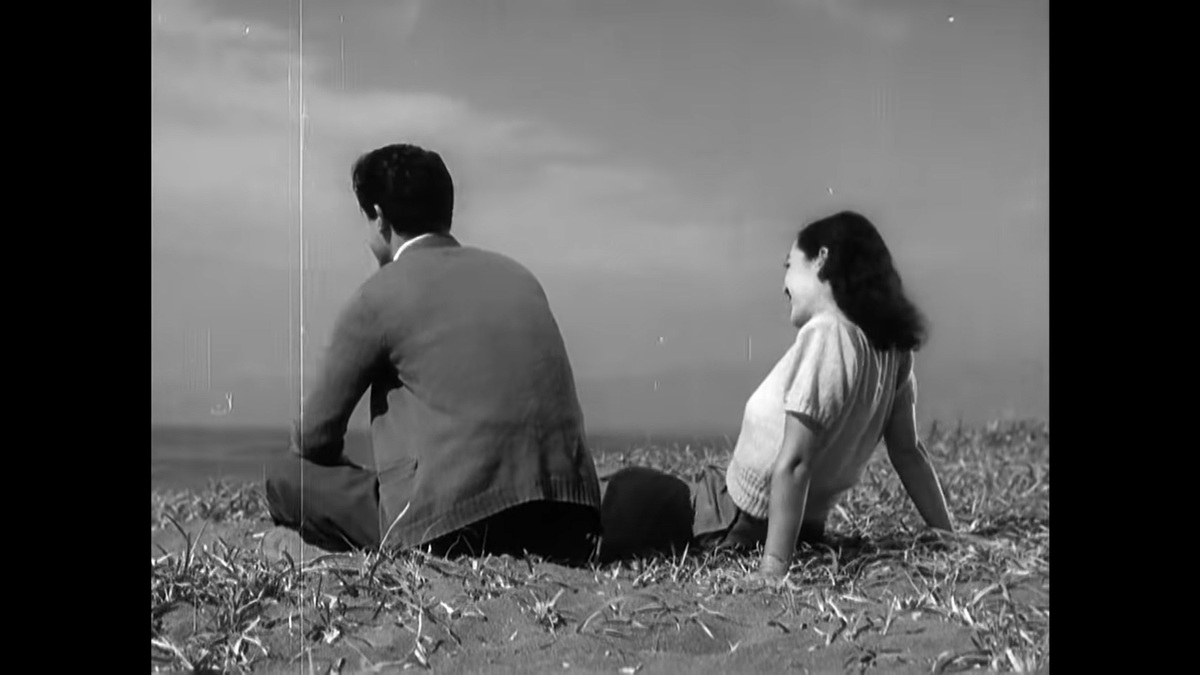

Ozu flips to the other side but uses the stationary bikes to acclimate us to the geography. Again he takes up most of the frame with nature, sky and ocean and sand and vegetation. It’s a beautiful day and even bicycles seem at peace with their surroundings.

As the characters sit down Ozu cuts to a closer shot. Again, this is essentially a zoom in on one section of the frame that was already there, only using a hard cut. Frames within frames.

Is it hot in here? Shots like this underscore how much this movie is a mainstream industry star vehicle. This is Old Hollywood-style glamor, not arthouse transcendentalism. The American influence here is just as strong as in the Coca-Cola sign.

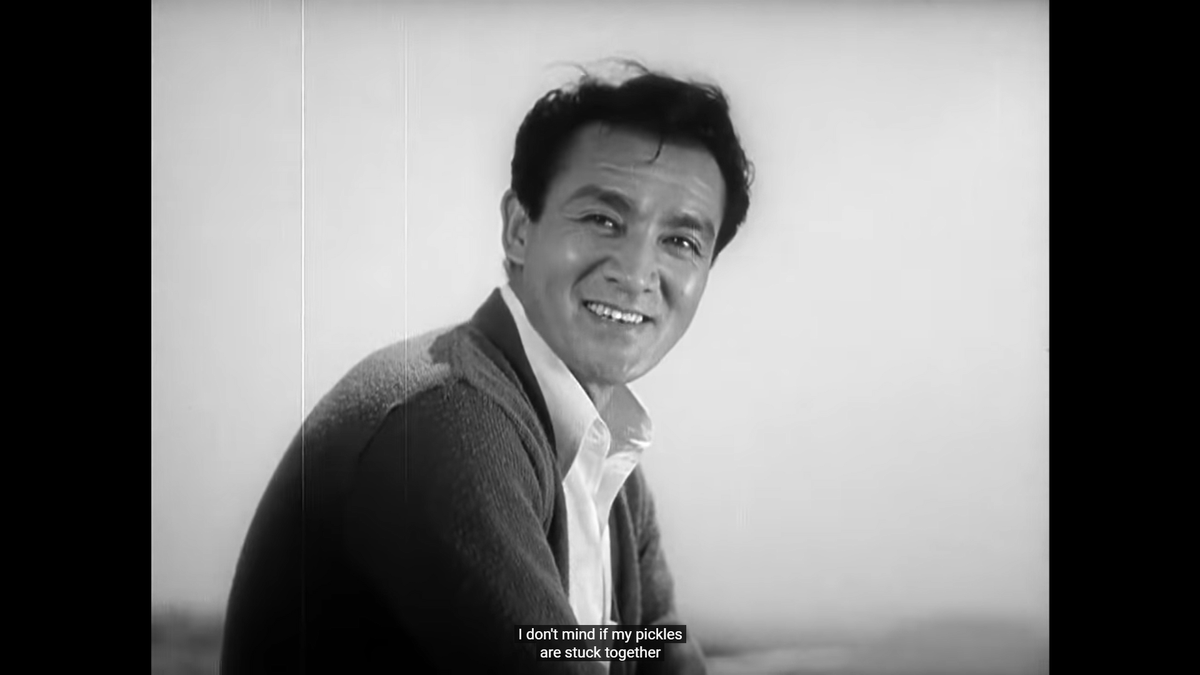

The conversation starts in the middle, implying that they’ve already begun with Shôichi talking about different types of women.

Shôichi and Noriko are unquestionably flirting here, as Noriko is teasing him and saying she’s jealous because her “pickles stick together.” Yowsa!

We are now at Aunt Masa’s house as the central conflict really begins. Shukichi begins the scene in a chair but moves to the floor; it’s a move likely made with aesthetics in mind but he’s also being brought back to tradition by the talk of his daughter’s need to be married.

We’re getting another ear full of tradition from Aunt Masa here. “Kids today” and whatnot. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">

To his credit, Shukichi is having none of it – it’s really a remarkable moment where he seems to be explaining to her that things aren’t like they used to be, even for us old fogies.

Aunt Masa knows he’s got her, but she tries to smoothly get the last word. Shukichi forces it on her, he won’t let her lie and say she wouldn’t eat sashimi with lipstick!

Note this is basically the same shot we opened with, but slightly closer in. There’s something in every bit of this frame, from the bottle in front to the laundry to the mirror to the tree and picket fence in the back.

Here comes one of the longest back-and-forth conversation sequences up to this point, just two medium shots of the characters as they discuss Noriko’s marriage status.

While Sugimura is looking directly at the camera, Ryû is looking slightly to our right. It’s not a zoom in from the previous establishing shots, though. We are slightly closer to Sugimura and moved in, as if we have taken the place of the bottle.

Aunt Masa is very aggressive and crafty in Late Spring. One of the more interesting dynamics at play in the movie is that the linking of change in the lives of the father and daughter and Japan’s shift from tradition to modernity is contradictory.

In reality, it is tradition – not modernity – that breaks the bond between father and daughter. Aunt Masa pushes for marriage because it’s the proper Japanese way, not because the world is evolving and Noriko must get with the times.

Aunt Masa, the firm traditionalist who is anti-sashimi for the bride, suggests the modern dresser Hattori, (sort of) named after the US occupation building, as a potential suitor. The traditionalist is the one pushing the new way onto the individual.

One of the great strengths of Ozu& #39;s work, especially in his late era which begins with this movie, is that characters are rarely if ever only one thing. Shukichi is thoughtful and caring about his daughter, but he& #39;s also a little clueless about what she wants or needs.

Aunt Masa is used as both a driver of the story and of comedy. She& #39;s the angel of death in so many ways that it& #39;s easy to forget she has the movie& #39;s funniest moments.

Here we are back on the long shot, which Ozu cuts to so we can get the full effect of Ryû& #39;s performance as he responds to the suggestion that Noriko might marry Hattori.

Aunt Masa& #39;s kimono underscores her role as the traditionalist. Ozu& #39;s films seem like they just plop into a contemporary Japanese setting already unleashed on the population, but in reality virtually everything is manufactured.

All of his interiors (and some of his exteriors) are sets, and everything is run by Ozu for approval - or in many cases chosen or created by Ozu himself.

Here& #39;s a wonderful article detailing an Ozu exhibit in Japan that displayed many items from his career, including fabric samples he selected to create the kimonos, curtains, and even paper for sliding doors. https://www.nippon.com/en/views/b03604/">https://www.nippon.com/en/views/...

This is an important point because in Ozu& #39;s films nothing is there by chance, it& #39;s built almost literally from the ground up.

We are back at the Somiya house now. Note that this shot appears to be slightly canted, which I think is an error.

It& #39;s tough to see in any one screengrab here, but Noriko is smiling while she folds the laundry. Lots has been written about Noriko smiling - there& #39;s even a whole book called that - but the real main point here is just that Noriko likes her routine, even at its most mundane.

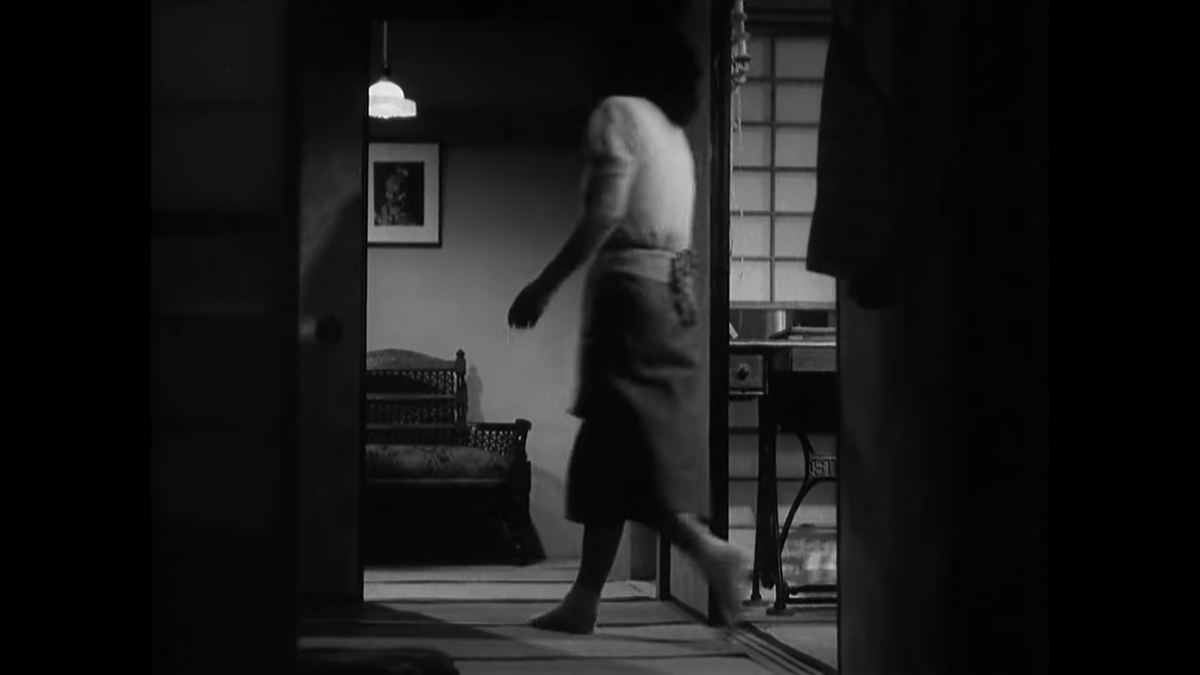

Here& #39;s the outside shot again, this time with Shukichi returning with the faint mission of making a match for Noriko. This will be the first interaction between the father and daughter about her potential to be married.

Here& #39;s Noriko going to greet Shukichi at the door. The geography of the rooms never feels quite right in an Ozu movie despite frequent uses of people moving from room to room and objects positioned in a way to orient you through cuts.

The filmmaker utilizes a sort of fractal geography when characters move between spaces; we accept they are in a real house filled with similarly proportioned rooms constructed out of similar frames that all make up a similar home. An infinite set of frames approaching reality.

A sharp cut as Shukichi whips around at the mention of Hattori. This is a POV shot despite the fact that Noriko isn& #39;t looking.

She finally turns to look as she changes the subject, oblivious to her father& #39;s almost comical tell. Rather than use a reverse POV, however, Ozu zooms in on his establishing shot.

Noriko explains they went cycling together. She doesn& #39;t mention the pickles.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">

Another 180 flip as we get a full view of Shukichi& #39;s now almost comical nervousness/excitement. Ozu holds on the room here even as Noriko leaves the room and Shukichi disappears behind a divider to deliver the full effect as he comes back into frame and follows Noriko.

Here& #39;s another repeated shot, the view into the kitchen which we first saw when Hattori let the worker in.

Here& #39;s the bathroom, a new angle on the house but with a composition that is nearly identical to the one used for the kitchen and for the hall where we returned to Noriko in the first shot of this scene. Check out the stack of books with vases here peeking out of an unknown room.

Back to the kitchen view as Noriko brings dinner to the table. The rhythm of this scene - so fraught with potential conflict for the film and Shukichi but with Noriko totally unaware - again demonstrates the effortless ballet of their domesticity.

This lovely shot from a new angle seems to have been lit for the dinner table where they will sit. They are shrouded in darkness often and even when they do sit, Noriko has her back to us and obscures Shukichi. Ozu even holds as they begin to eat in silence.

The dinner sequence is a straightforward shot series: two shots that are similar to a typical Hollywood over the shoulder shot and stay on the same side of the 180 line…

This is the most straightforward sequence in the film up to this point, but Ozu nevertheless keeps dynamic with his use of editing.

In this exchange, each shot is one line of dialogue, with the film cutting to each character as they speak their line.

Ozu cuts back here to the further shot for a longer exchange, allowing the viewer to get a full look at Shukichi as he quickly looks up when Noriko agrees that Hattori would make a good husband and makes the decision to lay his cards on the table.

Again Ozu cuts to the over-the-shoulder (around-the-body?) shot for a better look at the full-body response from Noriko, this time breaking down in laughter as she reveals that Hattori is in fact already engaged.

Ozu spends more time on Shukichi in this shot/reverse shot sequence as his response to this new information is more important and more in line with the audience’s situation.

Still, we do get a lot of Noriko as she tries to quickly shift the conversation to what gift they should get the couple when they are married.

Shukichi does his repeating thing here as he attempts to deal smoothly with his disappointment; this is the first real sign that he might be invested in the marrying off of his daughter in a way that Noriko herself is not.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="Conveniently, the pants happen to be right here, already wrapped for Noriko. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Conveniently, the pants happen to be right here, already wrapped for Noriko. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Don’t get too excited but this is the first time the camera moves in this movie. Of course, it’s just moving because it’s on a train; otherwise it’s just a boring old stationary shot! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Don’t get too excited but this is the first time the camera moves in this movie. Of course, it’s just moving because it’s on a train; otherwise it’s just a boring old stationary shot! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit lächelnden Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="We’re finally in Tokyo and we’re rewarded with this nice side shot of a beautiful building. This is not a random choice: this is the Hattori building which played a major role in the US occupation of Japan: it was the home of the film censorship board.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="We’re finally in Tokyo and we’re rewarded with this nice side shot of a beautiful building. This is not a random choice: this is the Hattori building which played a major role in the US occupation of Japan: it was the home of the film censorship board.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Our first look at the ocean is a link between the two men asking about its location and the following scene. We’re going to see a similar shot later! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😉" title="Zwinkerndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Zwinkerndes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Our first look at the ocean is a link between the two men asking about its location and the following scene. We’re going to see a similar shot later! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😉" title="Zwinkerndes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Zwinkerndes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Here’s a sign in English informing us that the capacity of the bridge is 30 tons. That’s 60,000lbs, a weight only relevant to loaded semis – or military vehicles. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Here’s a sign in English informing us that the capacity of the bridge is 30 tons. That’s 60,000lbs, a weight only relevant to loaded semis – or military vehicles. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🤔" title="Denkendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Denkendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">" title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="We’re getting another ear full of tradition from Aunt Masa here. “Kids today” and whatnot.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="We’re getting another ear full of tradition from Aunt Masa here. “Kids today” and whatnot.https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙄" title="Gesicht mit rollenden Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Gesicht mit rollenden Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Noriko explains they went cycling together. She doesn& #39;t mention the pickles. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Noriko explains they went cycling together. She doesn& #39;t mention the pickles. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😏" title="Grinsendes Gesicht" aria-label="Emoji: Grinsendes Gesicht">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>