75 years ago today the #WW2 officially came to end with the surrender of Imperial Japan. Amidst the celebrations and relief for millions at home and abroad, there was one group for whom the ordeal was still not over. Here’s the story of one such man – Ernest & #39;Ernie& #39; Beech

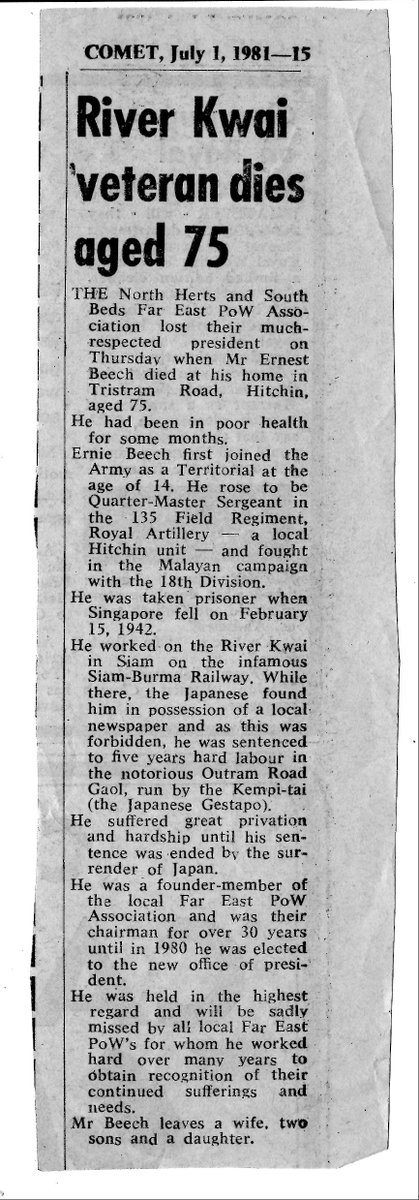

Born to a working-class family in Hertfordshire in 1905, Ernie had lived through both the Great War and the Spanish Flu by the time he was a teenager. On his fourteenth birthday he joined the local Territorial Army artillery unit and began his career as a part time soldier.

Between the wars Ernie was married and had three children. He rose through the ranks in the TA, eventually becoming Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant to the 135th (Hertfordshire Yeomanry) Regiment, RA. It was here he found himself in September 1939 when war was declared.

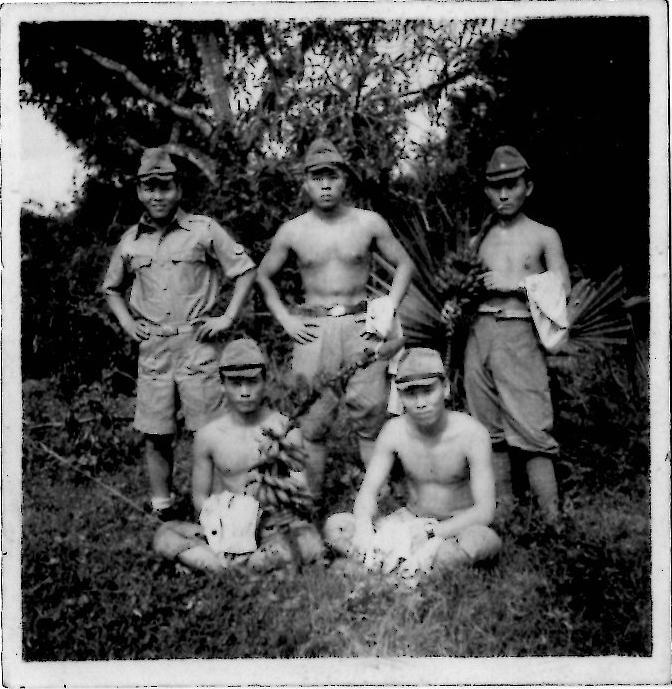

Ernie spent the first year on anti-invasion duties with the ill-fated 18th Division, before being told he was heading for Africa. Imperial Japan launching an attack at Pearl Harbour and on British possessions in the Far East in Dec 1941 changed all that – new destination: Malaya

Arriving into Singapore harbour in a monsoon in February 1942, Ernie and his comrades didn’t know it, but they were joining a desperate situation. Japanese forces had already driven British troops in the region back to Singapore Island and fighting was incredibly fierce.

Issued with obsolete artillery, and not much of that, the Herts Yeomanry joined the fighting for just a few days before withdrawing to ‘Fortress Singapore’, a formidable position on paper, but woefully prepared to face a landward attack.

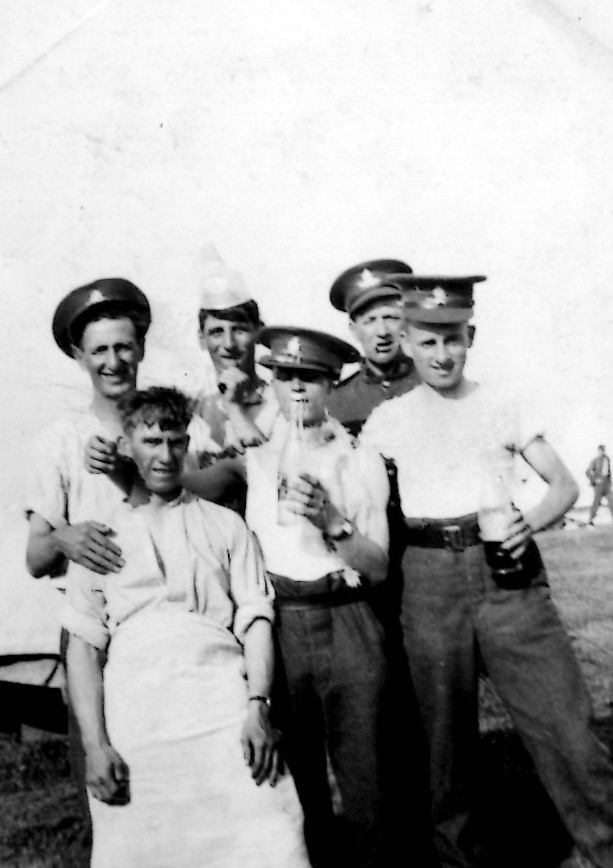

With a staff of 40, his group earned the nickname ‘Alley Barber and the Forty Thieves’. They had to work miracles every day. Each man was allotted only 24 ounces of rice per day; about 600 calories, which Ernie later recalled were ‘about half rice and half maggots’.

Week by week, month by month, the unspeakably harsh treatment took its toll on everyone. Men began to collapse with ulcers, dysentery and malaria. At first a few, then dozens each day. The food ration fell and the workload increased.

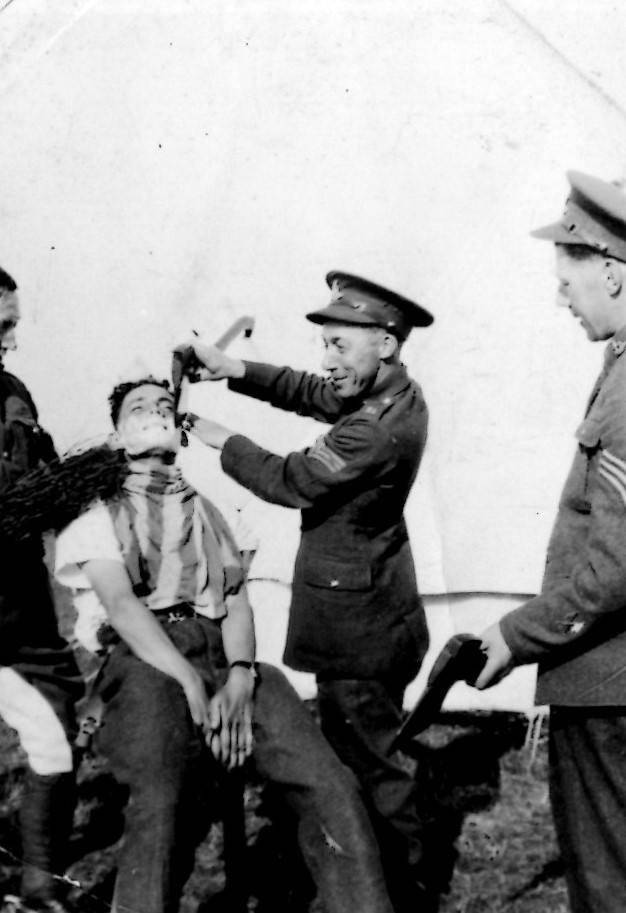

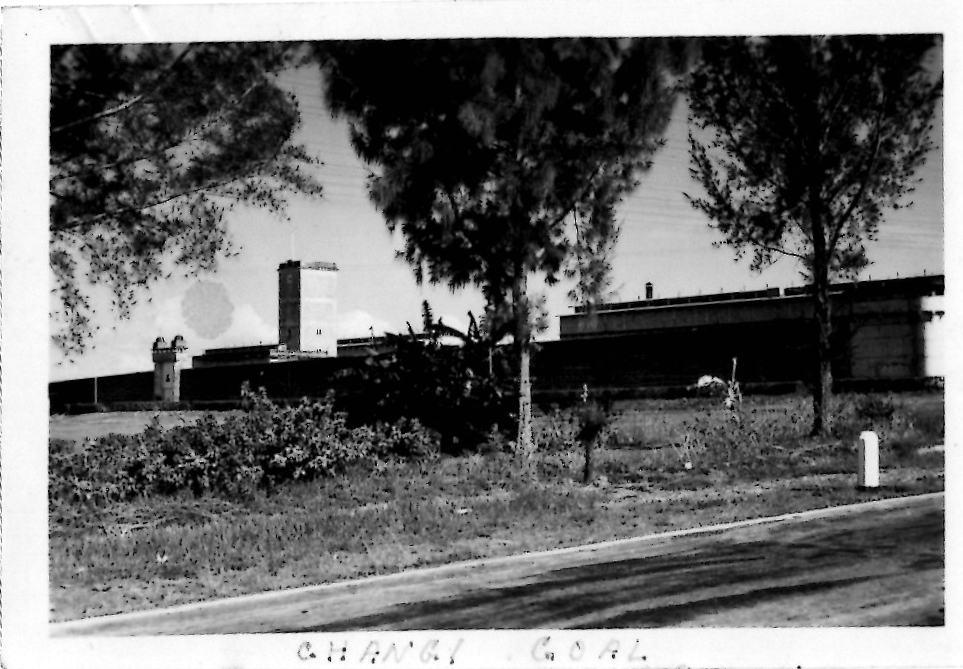

Stripped and beaten, Ernie was held in a 5 foot cage for a month. At over 6 feet tall, he was unable to stand or lie flat. When eventually released, he was partially blind and close to death. He was sentenced to 5 years in solitary confinement in the notorious Outram Road Gaol.

During that time, Ernie managed to make a few notes on scraps of paper he had hidden. One read “men walking about naked, glassy eyes and huge bones sticking out of their bodies, mad with hunger”. The guards at Outram were the Kenpeitai – the ‘Japanese Gestapo’.

75 years ago today Ernie was still there. For the prisoners at Outram Road, 15th August was just another day. Four days later with no word of surrender, Ernie was transferred back to a ‘normal’ prison camp. Little else changed; deaths didn’t stop, the illness still took its toll.

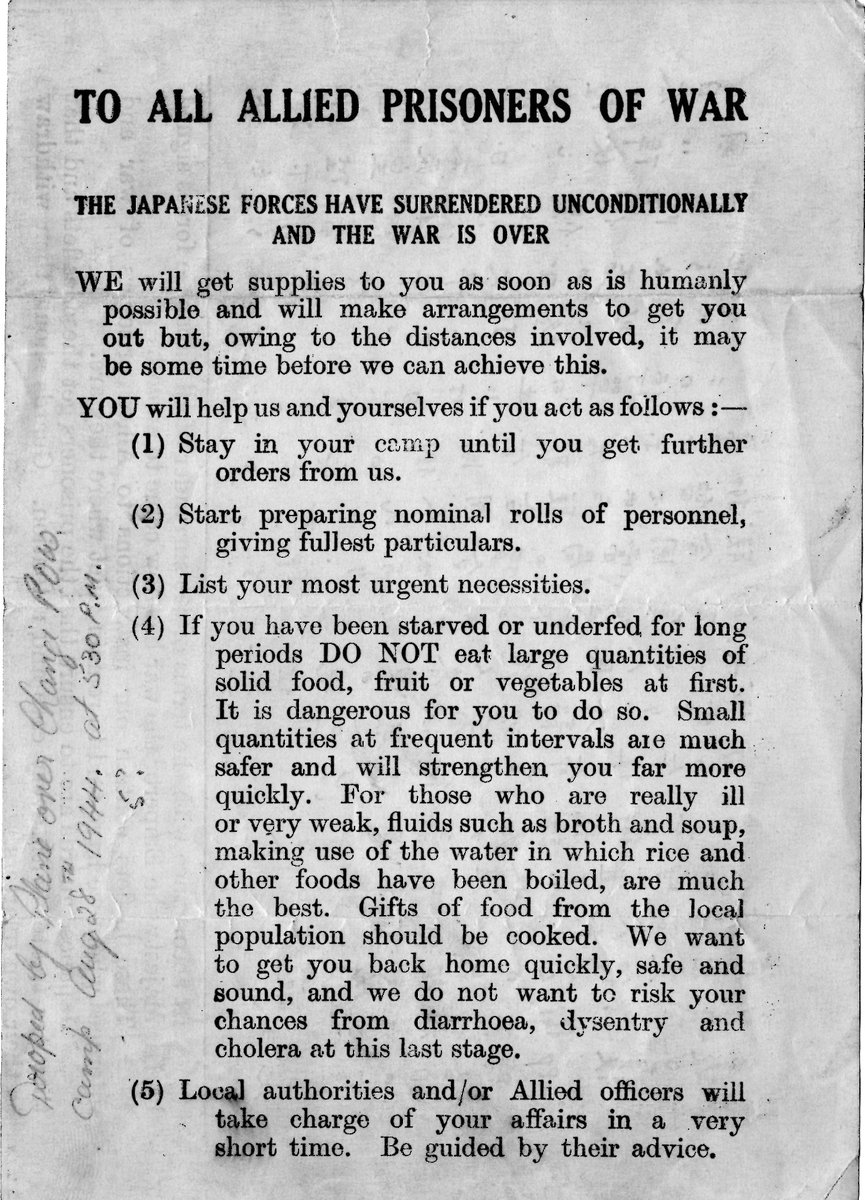

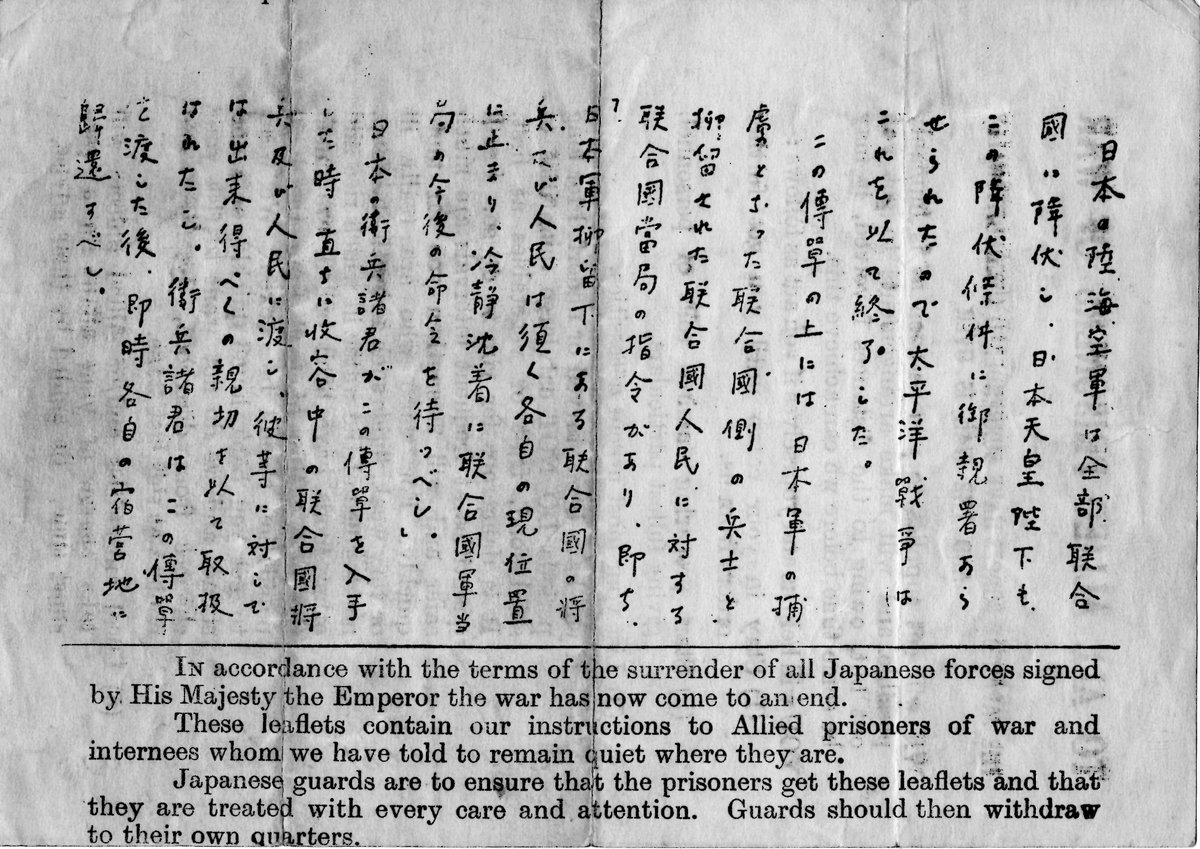

But then one morning the following week, a friendly aircraft was spotted circling the camp. It didn’t drop bombs, but leaflets, one of which Ernie kept for the rest of his life. At last, they knew the war was over.

When medical care eventually reached the camp almost the entire population were close to death. RQMS Beech had stood at 6 feet 1 tall in 1939 and weighed 14.5 stone. By the time he was released in 1945 he was a little over 7 stone.

By September 1945, Ernie and his mates were on board a friendly ship and heading home. So many more were not so lucky. Of the 7000 prisoners employed on the ‘railway of death’ alone, half would not return. Those who did, were forever scarred by their experiences.

After more than three years away, Ernie finally arrived home in October 1945. His wife had decorated their house for the occasion. She even photographed it. Ernie Beech has simply captioned the photo ‘Home. Worth fighting for’.

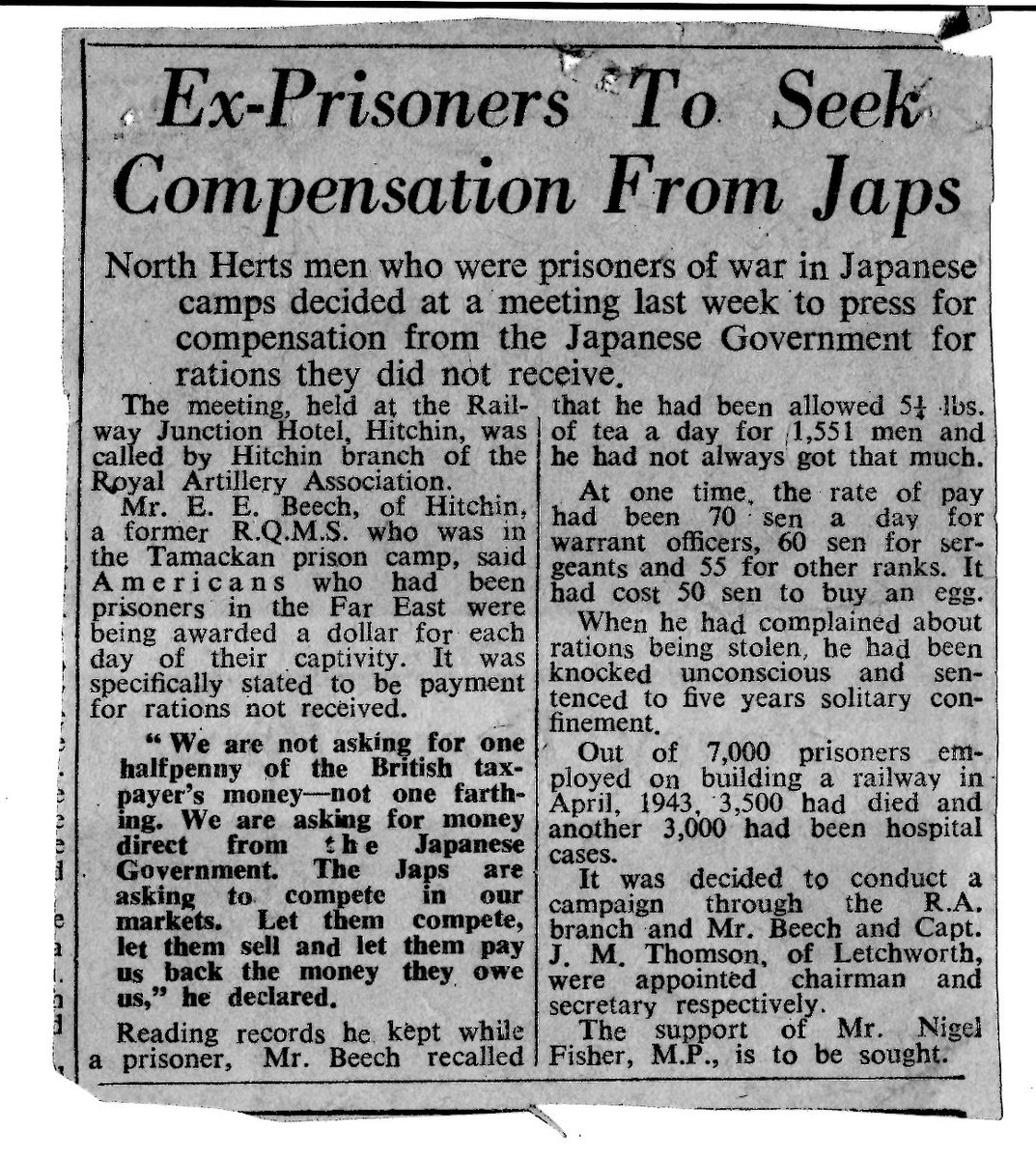

In the years after the war Ernie led a petition to the Japanese government that former prisoners should be compensated for their stolen rations during captivity. It took decades and a tremendous amount of effort, but eventually he was successful.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter