For centuries, Jews served as the "Other" for Europe’s Christians, as well as the objects of scholarly and ethnographic Enlightenment gaze. Within the Russian Empire, Yiddish publications were long banned, both to enforce Jewish Russification and to squelch Jewish revolution.

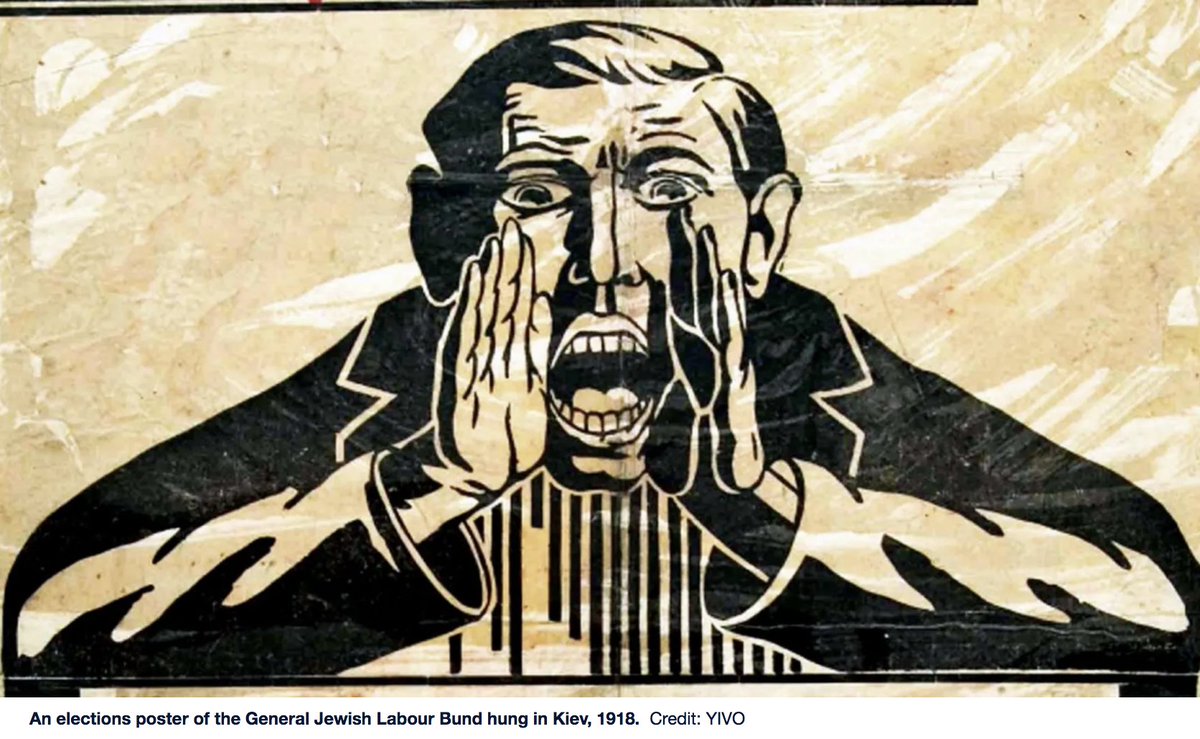

Since this is the age of the meme, the striking image of the Bund poster was modified and reproduced again and again, creating the impression of a resurgent, if reductive, neo-Bundism. The British-Jewish anarchist collective Jewdas sells a simplified version as a fundraiser.

The NYU chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace produced a modified version to protest a student trip to Israel. The International Socialist Organization used its imagery for a poster promoting BDS – incidentally, featuring some truly cringy Yiddish spelling mistakes.

Why has this 100-year-old election poster been taken up with such enthusiasm in (non-Yiddish speaking) antizionist and Palestine solidarity contexts? Its slogan rings like a voice of moral authority from the past, shouting in solidarity to the current antizionist moment.

Back then, “There where we live, there is our country” pointed to one of the key aspects of the Bundist movement: doikayt – literally, hereness.

"דאָרטן, ווו מיר לעבן, דאָרט איז אונדזער לאַנד"

"דאָרטן, ווו מיר לעבן, דאָרט איז אונדזער לאַנד"

As a contemporary rhetorical move, emphasizing “hereness” mitigates “thereness,” that is to say, theoretical Jewish obligations to, and responsibility for, the State of Israel. It posits a starkly bad "there" (Israel), while implying an unproblematic here.

But where, exactly, is here? Is it New York? The reconstituted, prosperous capital of global Jewry? Or is “here” Lenapehoking, home of the indigenous Lenape people, who lived on what is now known as Manhattan, before they were dispossessed (again and again) by European settlers?

It is a historical irony that Bundist hereness can, in one breath, be used to condemn Zionism as a fascist settler-colonial state, and in the next breath, be used to proclaim as anti-fascist a Jewish person’s mere existence within a different settler-colonial state.

Though the Bund was strongly against the establishment of a Jewish state in Israel, the original context of doikayt wasn’t a negation of Zionism. For one thing, it was a reaction to the dire economic situation in Eastern Europe, as well as rising antisemitism.

The transposition of pre-war Yiddish socialist poetics onto a different world, a century later is a kind of violent Othering. It allows participants to identify as Jews, while remaining distanced from the embarrassments of the past, as well as from Zionism.

By privileging anti-Zionism above all else, it attempts to purify Jewishness of its “outdated” nationalism, cherry picking the past for elements compatible with (a certain part of) contemporary post-colonial left praxis.

Without a substantive, positive, historically grounded vision for Jewish life in the Diaspora, the contemporary vogue for doikayt risks becoming an ironic parody of the Zionist negation of the Diaspora, but with a demonized image of the State of Israel as its animating idea.

This thread is from an article by Rokhl Kafrissen is a Yiddishist, playwright and cultural critic who lives in New York. https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/.premium-why-modern-anti-zionists-love-the-bund-1.8323974">https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/.p...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter