1/

Something happened. That wasn& #39;t supposed to happen.

Or rather.

Something didn& #39;t happen. That was supposed to happen.

Eyes wide like saucers, they told me. Tears glistened in their eyes.

Them: "I made a #medicalerror."

Me: *listening*

They were accountable. They were.

Something happened. That wasn& #39;t supposed to happen.

Or rather.

Something didn& #39;t happen. That was supposed to happen.

Eyes wide like saucers, they told me. Tears glistened in their eyes.

Them: "I made a #medicalerror."

Me: *listening*

They were accountable. They were.

2/

Did anything happen as a result? No.

But something could have happened. Something disastrous and bad. Lucky us, it did not.

They knew that.

I knew that, too.

I was the attending. This was my responsibility, too.

So I said that.

Me: "I& #39;m responsible, too."

Did anything happen as a result? No.

But something could have happened. Something disastrous and bad. Lucky us, it did not.

They knew that.

I knew that, too.

I was the attending. This was my responsibility, too.

So I said that.

Me: "I& #39;m responsible, too."

3/

That didn& #39;t make them feel better. But I did need them to know that it was my error, too.

It was.

We needed to debrief. Wait. Maybe this was supposed to be the debrief.

Hmmm.

I thought about all the ways that has looked throughout my training and beyond.

Yup.

That didn& #39;t make them feel better. But I did need them to know that it was my error, too.

It was.

We needed to debrief. Wait. Maybe this was supposed to be the debrief.

Hmmm.

I thought about all the ways that has looked throughout my training and beyond.

Yup.

4/

If the supervising physician was into tough love? The approach was simple & predictable:

1. Shame.

2. Blame.

3. Retrain.

You hung your head. Or you stood on rounds feeling relieved that it wasn& #39;t you under fire.

Feeling like shit was the alleged panacea.

If the supervising physician was into tough love? The approach was simple & predictable:

1. Shame.

2. Blame.

3. Retrain.

You hung your head. Or you stood on rounds feeling relieved that it wasn& #39;t you under fire.

Feeling like shit was the alleged panacea.

5/

If the supervising physician was more of an empath? You got a carefully chosen story of their own error.

1. It is worse than yours.

2. Normalizing statements follow.

3. You are told that humans are imperfect.

But you still feel bad.

Or sad.

So you tuck it away.

If the supervising physician was more of an empath? You got a carefully chosen story of their own error.

1. It is worse than yours.

2. Normalizing statements follow.

3. You are told that humans are imperfect.

But you still feel bad.

Or sad.

So you tuck it away.

6/

The empathic approach may also be blended with some questions about how you feel.

Which are still almost always followed by tales of equally disastrous events and revelations of this acceptance of being mere mortals.

And you still don& #39;t feel better.

Nope.

The empathic approach may also be blended with some questions about how you feel.

Which are still almost always followed by tales of equally disastrous events and revelations of this acceptance of being mere mortals.

And you still don& #39;t feel better.

Nope.

7/

If it happens enough, you start to fold into yourself. You don& #39;t trust your thinking. Your imposter syndrome explodes into a fire breathing dragon.

Little voice: "You are terrible. You do not deserve to be here."

Even when the patient extends grace. You don& #39;t believe it.

If it happens enough, you start to fold into yourself. You don& #39;t trust your thinking. Your imposter syndrome explodes into a fire breathing dragon.

Little voice: "You are terrible. You do not deserve to be here."

Even when the patient extends grace. You don& #39;t believe it.

8/

And eventually, you feel burnt out.

Which leads to more errors.

Which leads to more burnout.

A vicious cycle, man.

And here& #39;s what is true:

Shame doesn& #39;t work.

Nor does a nondescript chuck under the chin.

No. It. Does. Not. https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2018/10/qa-physician-burnout-linked-to-major-errors.htm">https://acphospitalist.org/archives/...

And eventually, you feel burnt out.

Which leads to more errors.

Which leads to more burnout.

A vicious cycle, man.

And here& #39;s what is true:

Shame doesn& #39;t work.

Nor does a nondescript chuck under the chin.

No. It. Does. Not. https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2018/10/qa-physician-burnout-linked-to-major-errors.htm">https://acphospitalist.org/archives/...

9/

Several years ago, I began thinking a lot about this. Here were my main questions:

1. How can I gain closure?

2. How can I make sure this doesn& #39;t happen again?

3. How can I be accountable without punishing myself indefinitely?

4. How can I honor the patient?

Hmmm.

Several years ago, I began thinking a lot about this. Here were my main questions:

1. How can I gain closure?

2. How can I make sure this doesn& #39;t happen again?

3. How can I be accountable without punishing myself indefinitely?

4. How can I honor the patient?

Hmmm.

10/

I realized also that every person involved has a different level of responsibility and hence unique emotions surrounding the adverse event.

Each person needs a way to process.

Attending.

Resident.

Intern.

Student.

APP.

Nurse.

and anyone else involved in care.

I realized also that every person involved has a different level of responsibility and hence unique emotions surrounding the adverse event.

Each person needs a way to process.

Attending.

Resident.

Intern.

Student.

APP.

Nurse.

and anyone else involved in care.

11/

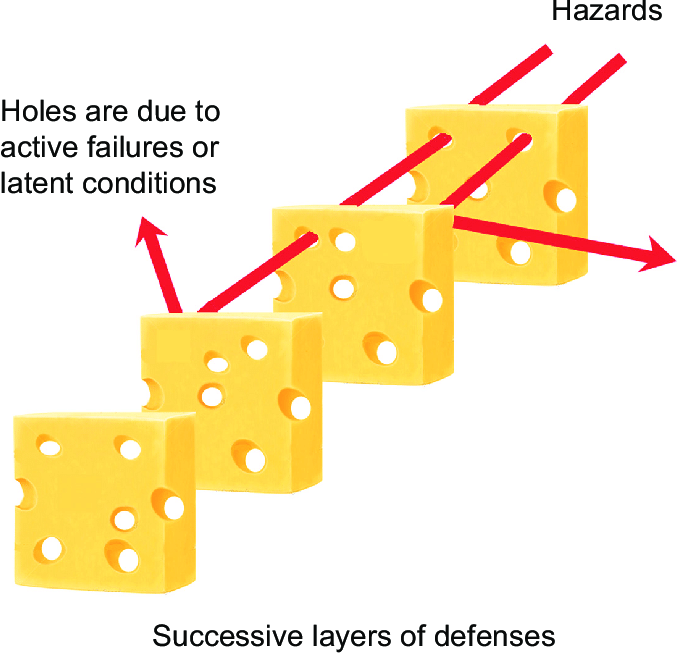

So here& #39;s what I eventually came up with--a set of questions for EACH individual involved to work through.

Why?

Because what each of us feels in terms of where we stand in the stack of Swiss cheese can be vastly different.

Let me explain.

So here& #39;s what I eventually came up with--a set of questions for EACH individual involved to work through.

Why?

Because what each of us feels in terms of where we stand in the stack of Swiss cheese can be vastly different.

Let me explain.

12/

Perhaps the student did all they could in the scope of their role. Or the intern made a suggestion that got ignored.

Maybe the resident didn& #39;t carefully review the discharge with the intern. And the attending simply signed the discharge summary without looking close.

Hmmm.

Perhaps the student did all they could in the scope of their role. Or the intern made a suggestion that got ignored.

Maybe the resident didn& #39;t carefully review the discharge with the intern. And the attending simply signed the discharge summary without looking close.

Hmmm.

13/

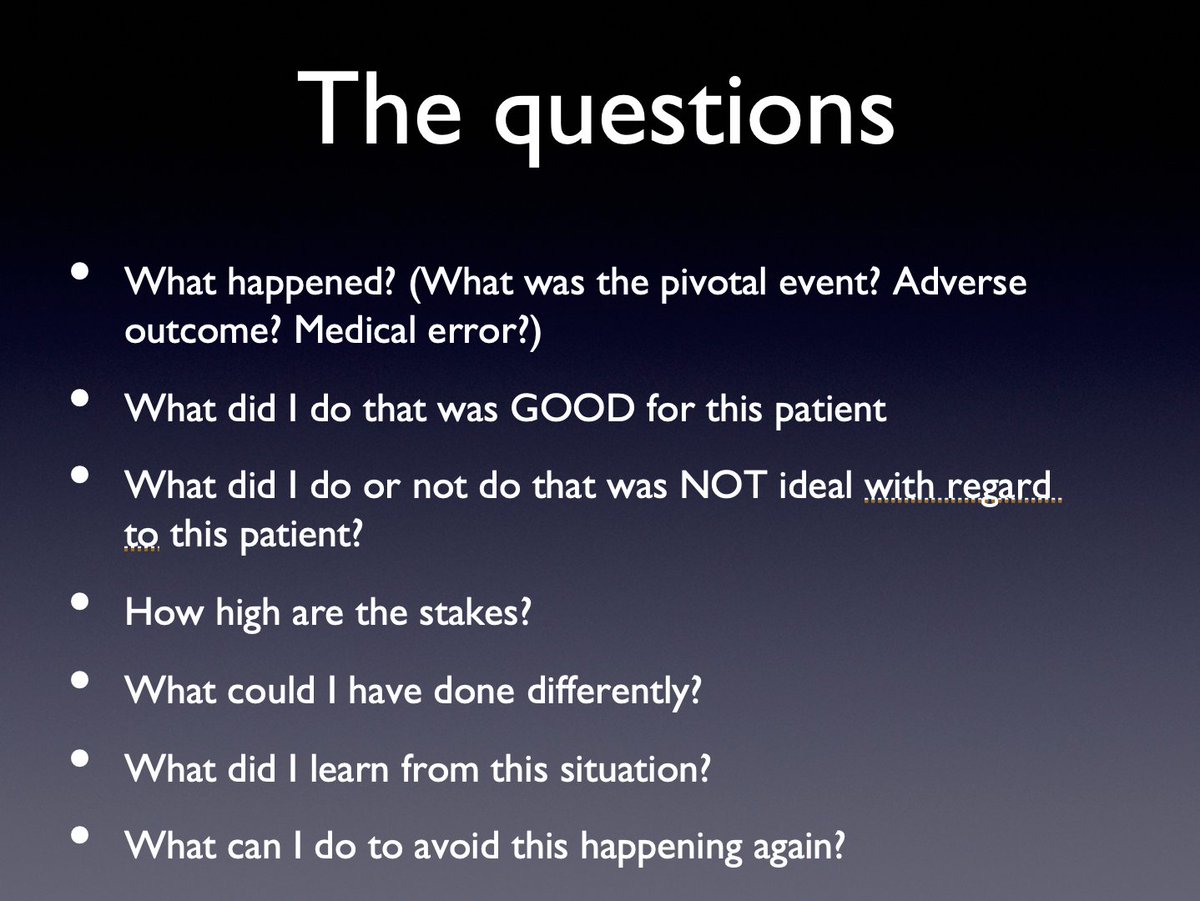

And so.

Here are the questions I use to debrief with my teams.

And also with myself.

They allow a specific unpacking. And it helps me because it allows us to explore our individual roles in the adverse event.

We share our answers out loud (unless someone is too upset.)

And so.

Here are the questions I use to debrief with my teams.

And also with myself.

They allow a specific unpacking. And it helps me because it allows us to explore our individual roles in the adverse event.

We share our answers out loud (unless someone is too upset.)

13/

And let me draw your attention to the one most often forgotten:

What did you do that was GOOD for this patient?

Why? Because the patients we pour into the most are the ones that we feel the most awful about.

So it IS good to take a moment to point out what went right.

And let me draw your attention to the one most often forgotten:

What did you do that was GOOD for this patient?

Why? Because the patients we pour into the most are the ones that we feel the most awful about.

So it IS good to take a moment to point out what went right.

14/

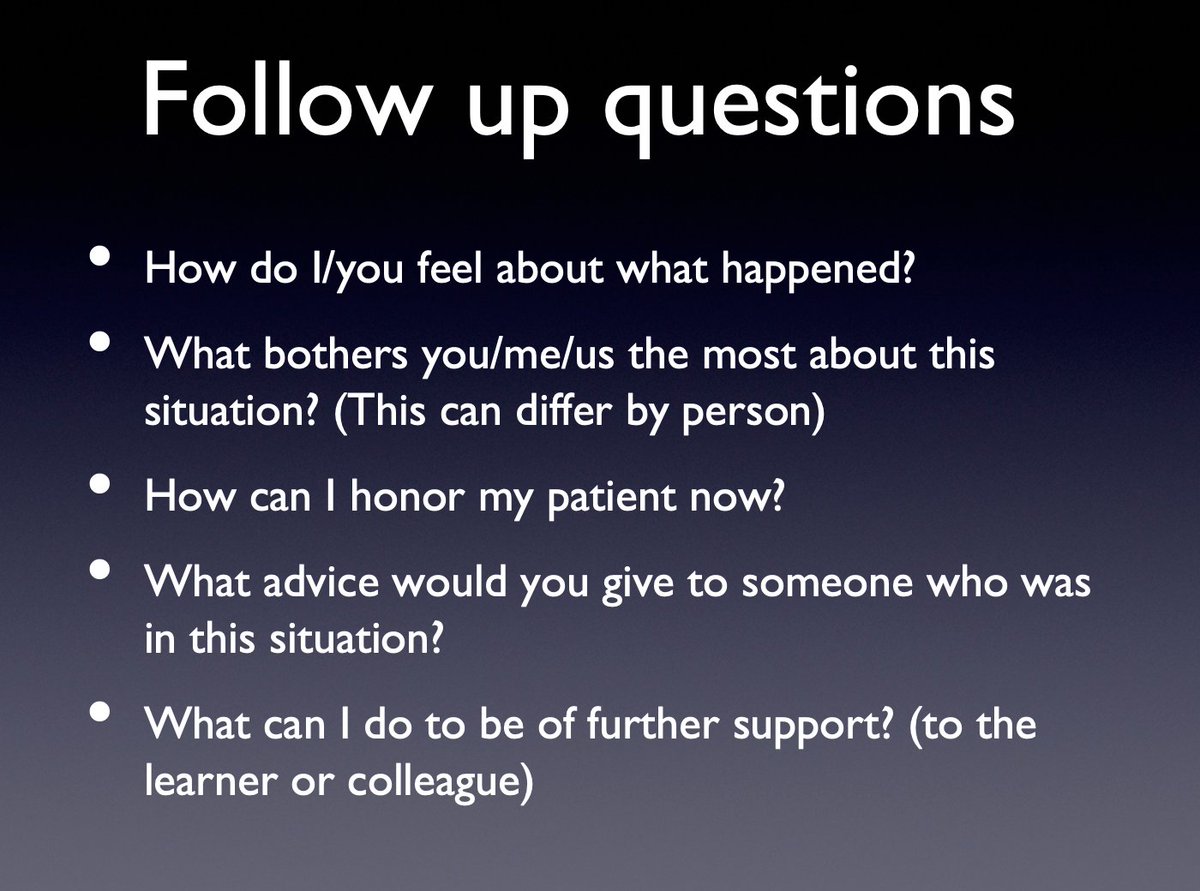

Next come the follow up questions. These get pretty personal but prove quite therapeutic.

I like this because it takes the place of the "when I was an intern" stories, stinging indifference, or shaming.

And it lets the team heal together.

Next come the follow up questions. These get pretty personal but prove quite therapeutic.

I like this because it takes the place of the "when I was an intern" stories, stinging indifference, or shaming.

And it lets the team heal together.

15/

I should also mention that these questions give us permission to work through any event that didn& #39;t go as planned--alone, too.

Example:

Patient gets an IV placed that they didn& #39;t need. You forgot to D/C the order.

You: "I feel bad."

Them: "It was just an IV! Relax!"

I should also mention that these questions give us permission to work through any event that didn& #39;t go as planned--alone, too.

Example:

Patient gets an IV placed that they didn& #39;t need. You forgot to D/C the order.

You: "I feel bad."

Them: "It was just an IV! Relax!"

16/

But to you, it was invasive. It was unnecessary. It was wrong.

And nestled in that IS an opportunity to honor the patient by making changes so you can avoid this happening again.

You: "I will communicate with nursing about my plans to avoid this in the future."

But to you, it was invasive. It was unnecessary. It was wrong.

And nestled in that IS an opportunity to honor the patient by making changes so you can avoid this happening again.

You: "I will communicate with nursing about my plans to avoid this in the future."

17/

And so.

As a team, we unpacked the adverse event--starting with me. Sharing ownership of the error--since systems involve many people--is helpful.

At least that& #39;s what I think.

Anyway.

Together we came up with ways to honor our patient. And also to move on.

And so.

As a team, we unpacked the adverse event--starting with me. Sharing ownership of the error--since systems involve many people--is helpful.

At least that& #39;s what I think.

Anyway.

Together we came up with ways to honor our patient. And also to move on.

18/

And, of course, all of this comes after we attend to the pt & disclose what happened to them.

That& #39;s always step one.

But over the years I& #39;ve learned that this cloak of grief that settles on us when things go wrong gets heavy.

Very heavy.

And hurts more than just us. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👊🏾" title="Fisted hand (durchschnittlich dunkler Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Fisted hand (durchschnittlich dunkler Hautton)">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👊🏾" title="Fisted hand (durchschnittlich dunkler Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Fisted hand (durchschnittlich dunkler Hautton)">

And, of course, all of this comes after we attend to the pt & disclose what happened to them.

That& #39;s always step one.

But over the years I& #39;ve learned that this cloak of grief that settles on us when things go wrong gets heavy.

Very heavy.

And hurts more than just us.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter