Last week I was interviewed for a podcast about hydroxychloroquine.

As we were wrapping up, the producer interjected and asked “Some doctors say it works, others say it doesn’t. As a layperson, who should I believe?”

Great question. Here& #39;s the answer.

/1

As we were wrapping up, the producer interjected and asked “Some doctors say it works, others say it doesn’t. As a layperson, who should I believe?”

Great question. Here& #39;s the answer.

/1

To know whether a drug “works” or not, we need to test it.

How? By giving it to people and watching what happens to them.

We look for any benefits (the things we hope the drug does) as well as any side effects.

/2

How? By giving it to people and watching what happens to them.

We look for any benefits (the things we hope the drug does) as well as any side effects.

/2

But we don& #39;t just give it to people. That’s not helpful.

Why not?

Imagine you have a sore throat caused by a virus. It gets progressively worse.

A friend says "You know, maybe it& #39;s strep" and offers you some antibiotics. You take them.

/3

Why not?

Imagine you have a sore throat caused by a virus. It gets progressively worse.

A friend says "You know, maybe it& #39;s strep" and offers you some antibiotics. You take them.

/3

A few days later, you& #39;re better. The antibiotic helped, right?

No. Because it couldn’t have.

The sore throat was caused by a virus, and antibiotics do nothing for those.

You got better because THAT& #39;S WHAT HAPPENS with viral throat infections.

/4

No. Because it couldn’t have.

The sore throat was caused by a virus, and antibiotics do nothing for those.

You got better because THAT& #39;S WHAT HAPPENS with viral throat infections.

/4

No, to properly test a drug—to really, genuinely know if it works or not—you need to *compare it* to something.

And the best thing to compare it to is usually a placebo: a “sugar pill” with no effects of its own, good or bad.

/5

And the best thing to compare it to is usually a placebo: a “sugar pill” with no effects of its own, good or bad.

/5

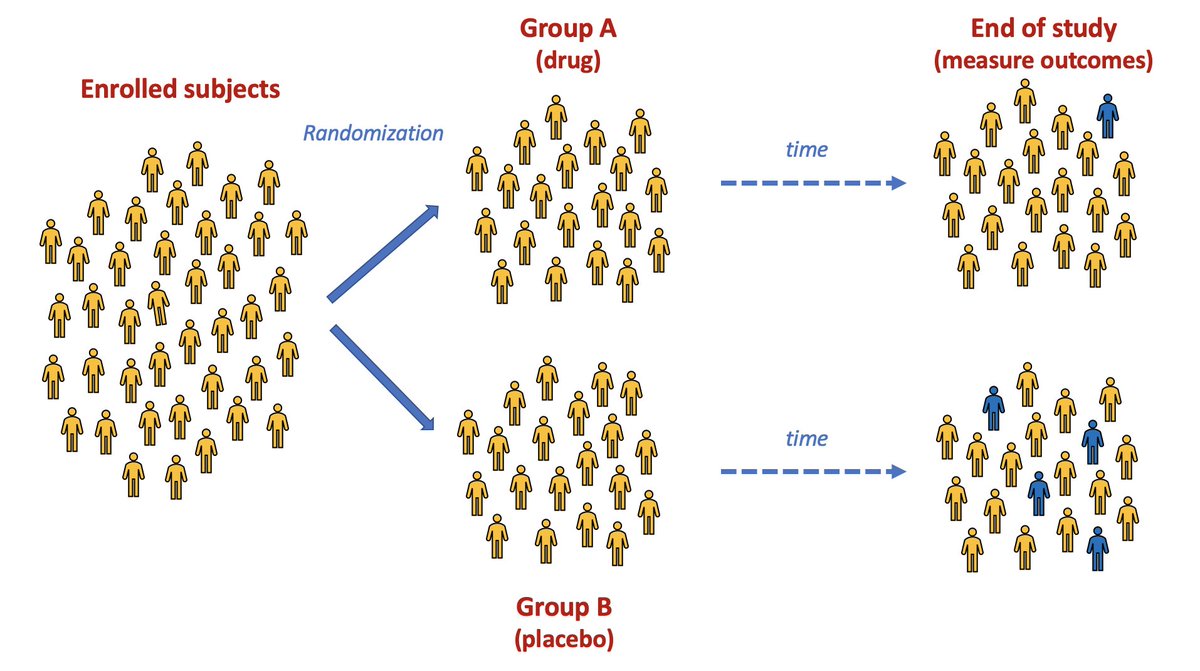

This kind of comparison is called a placebo-controlled trial.

It is literally an experiment on a group of people.

Some get the drug (the “intervention group") and some get the placebo (the “control group").

/6

It is literally an experiment on a group of people.

Some get the drug (the “intervention group") and some get the placebo (the “control group").

/6

But here’s the really, really important part:

The two groups need to be as similar as possible at the start of the study.

And with the exception of drug or placebo, they should be treated more or less the same during the course of the study.

Why is this so important?

/7

The two groups need to be as similar as possible at the start of the study.

And with the exception of drug or placebo, they should be treated more or less the same during the course of the study.

Why is this so important?

/7

Because it means the groups differ in only one important way: one got the drug and the other one didn& #39;t.

As a result, any difference in how the groups do (in terms of symptoms or survival or whatever) has only one explanation:

The drug.

/8

As a result, any difference in how the groups do (in terms of symptoms or survival or whatever) has only one explanation:

The drug.

/8

To do a study like this, first we identify a group of people who might benefit from the drug.

Then we divide them into two comparable groups.

How? By flipping a coin, more or less.

Heads you get drug, tails you get placebo.

In other words, it& #39;s random.

/9

Then we divide them into two comparable groups.

How? By flipping a coin, more or less.

Heads you get drug, tails you get placebo.

In other words, it& #39;s random.

/9

Enrol enough patients and flip enough coins and you& #39;ll end up with two very similar groups.

They’ll be comparable for things we can measure (weight, smoking, and so on) but also things we can’t (genetic factors, etc.)

And therein lies the beauty of randomization.

/10

They’ll be comparable for things we can measure (weight, smoking, and so on) but also things we can’t (genetic factors, etc.)

And therein lies the beauty of randomization.

/10

This type of study is a called a "randomized controlled trial" (RCT), and it& #39;s the only way of really knowing whether a drug works or not.

Here& #39;s a conceptual RCT in which the drug appears to do something. (Seems to reduce the risk of turning blue.)

/11

Here& #39;s a conceptual RCT in which the drug appears to do something. (Seems to reduce the risk of turning blue.)

/11

So, which doctors should you believe about the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

The ones whose views derive from RCTs.

It really is as simple as that.

And what do RCTs tell us?

/12

The ones whose views derive from RCTs.

It really is as simple as that.

And what do RCTs tell us?

/12

After exposure to SARS-CoV-2, hydroxychloroquine doesn& #39;t significantly lower the risk of infection https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2016638">https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/...

/13

/13

Among outpatients with early COVID-19, hydroxychloroquine doesn& #39;t significantly reduce symptoms https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-4207

/14">https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.73...

/14">https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.73...

In hospitalized patents with mild to moderate COVID-19, hydroxychloroquine (three weeks of it!) doesn& #39;t help clear the virus https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1849">https://www.bmj.com/content/3...

/15

/15

In hospitalized patients with mild-moderate COVID-19, hydroxychloroquine doesn& #39;t improve symptoms, whether or not it& #39;s combined with azithromycin https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2019014

/16">https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/...

/16">https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/...

There are other RCTs, and @methodsmanmd has summarized them all here. No doubt we& #39;ll see more in the months ahead. https://twitter.com/methodsmanmd/status/1291072016121049091?s=20

/17">https://twitter.com/methodsma...

/17">https://twitter.com/methodsma...

To sum up:

- Only RCTs can tell us if a drug works or not.

- The RCTs of hydroxychloroquine are overwhelmingly negative.

/18

- Only RCTs can tell us if a drug works or not.

- The RCTs of hydroxychloroquine are overwhelmingly negative.

/18

Having said that, I& #39;ll add this:

Hydroxychloroquine is nowhere near as dangerous as some have suggested. It& #39;s actually a pretty safe drug.

But that is a thread for another day.

/ end (for now)

Hydroxychloroquine is nowhere near as dangerous as some have suggested. It& #39;s actually a pretty safe drug.

But that is a thread for another day.

/ end (for now)

Here& #39;s the podcast. The sooner we stop talking about hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, the better. https://twitter.com/JAMA_current/status/1294296970140549122?s=20">https://twitter.com/JAMA_curr...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter