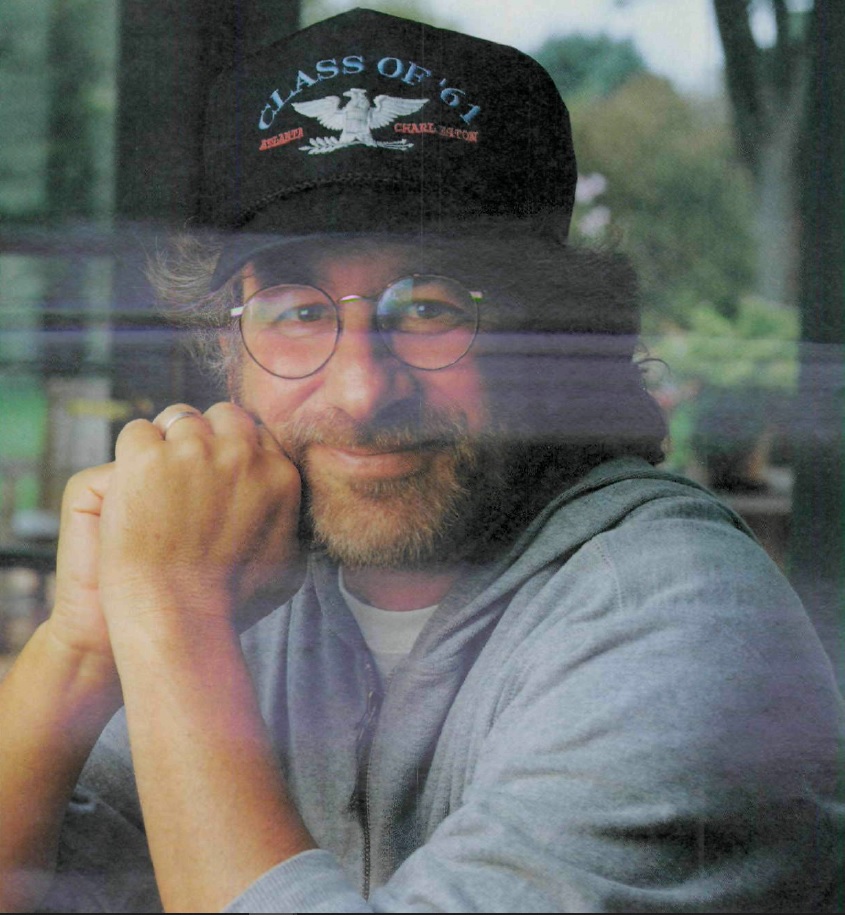

Today, I learned from Steven Spielberg about the movie business and about the importance of understanding the commercial side as an artist.

Steve started early. At age 12 he screened movies in his family& #39;s living room with his father& #39;s projector.

His sisters sold tickets, his mother helped with popcorn and soda.

"We all worked for Steve," his mother said. "From the minute he was born, I was his employee."

His sisters sold tickets, his mother helped with popcorn and soda.

"We all worked for Steve," his mother said. "From the minute he was born, I was his employee."

When he was 16 years old, he spent the summer in LA. He sneaked on the Universal studio lot and walked up to famous director John Ford (four Oscars as best director).

This was Ford& #39;s advice: "Never spend your own money to make a movie. Now get the hell out of here."

This was Ford& #39;s advice: "Never spend your own money to make a movie. Now get the hell out of here."

Spielberg became obsessed with making movies. Even though his grades weren& #39;t good enough for a top film school, one of his amateur movies gets the attention of Sidney Sheinberg, then head of TV at Universal.

Spielberg gets a seven year contract, starting at $275 a week.

Spielberg gets a seven year contract, starting at $275 a week.

After a few years of directing TV films, he got the opportunity to make Jaws. It almost ended in disaster.

"It was the fact that we had the hubris to shoot on the ocean, and not in a tank."

Shooting on the ocean lead to delays. The film ran over budget.

"It was the fact that we had the hubris to shoot on the ocean, and not in a tank."

Shooting on the ocean lead to delays. The film ran over budget.

"I had to just keep moving forward. The schedule was dictated by the mechanical shark and the weather conditions on the ocean."

Sheinberg was there for him: "I think every time there was an intention to replace me, Sid stepped in quietly." "Because Sid believed in me."

Sheinberg was there for him: "I think every time there was an intention to replace me, Sid stepped in quietly." "Because Sid believed in me."

"He came out one day and he said, & #39;Do you really think you’re ever going to finish this movie?& #39;

& #39;I will finish this film. I can’t tell you what day I’ll finish this picture, but I will finish this picture.& #39; And Sid let me continue."

& #39;I will finish this film. I can’t tell you what day I’ll finish this picture, but I will finish this picture.& #39; And Sid let me continue."

Spielberg finished the movie which turned out to be a blockbuster and crushed the box office record.

Now he got a business crash course from what he called the "Brooks Brothers realists" (the suits): Sheinberg, Steve Ross, Guy McElwaine and Terry Semel.

"I don& #39;t think it made me Brooks Brothers or a realist, but it gave me a real good primer on the film industry."

"I don& #39;t think it made me Brooks Brothers or a realist, but it gave me a real good primer on the film industry."

"Guy took me to Terry& #39;s house so Terry could sit me down and explain distribution, which I knew nothing about. Terry must have talked for four hours straight. And I was taking notes. And at the end of the day, I knew more about distribution and exhibition than I ever wanted to."

After Jaws, doors opened up. He had been pitching "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" without success.

"The minute Jaws hit the theaters, they started to say yes. For the first time I sat back and thought, & #39;Well, that& #39;s really interesting. Success begets opportunity.& #39;"

"The minute Jaws hit the theaters, they started to say yes. For the first time I sat back and thought, & #39;Well, that& #39;s really interesting. Success begets opportunity.& #39;"

For Close Encounters he negotiated 17.5% of the profits. And received a lesson in Hollywood accounting.

The movie grossed $300 million but Spielberg made only $5 million - from the slim profit remaining after deducting overhead, interest, distribution and other fees.

The movie grossed $300 million but Spielberg made only $5 million - from the slim profit remaining after deducting overhead, interest, distribution and other fees.

A share of profits was disappointing. But no director since Alfred Hitchcock had received "gross points" - a percentage of revenues.

Two years later in 1977, Spielberg was on vacation in Hawaii with another director wunderkind: George Lucas.

Lucas was worried about the Star Wars premiere. When the opening turned out to be a success, he relaxed and was "suddenly laughing again."

Lucas was worried about the Star Wars premiere. When the opening turned out to be a success, he relaxed and was "suddenly laughing again."

In a good mood, he told Spielberg about an idea to make "a series of archaeology films." They developed the idea of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Lucas wanted control, he wanted ownership of the movie.

What did Spielberg want? "I want gross."

Lucas wanted control, he wanted ownership of the movie.

What did Spielberg want? "I want gross."

It wasn& #39;t an easy pitch with a huge budget of $20mm. And there was concern about cost discipline -Lucas& #39;s The Empire Strikes Back cost $33mm instead of $18.

Plus the deal terms: Lucas wanted to own 50% of the movie rights and have full control. And Spielberg wanted 10% gross.

Plus the deal terms: Lucas wanted to own 50% of the movie rights and have full control. And Spielberg wanted 10% gross.

Most studios passed. Universal& #39;s Sheinberg called the deal "absurd" and didn& #39;t even bother with a counteroffer.

They ended up negotiating with Michael Eisner at Paramount and Frank Wells at Warner (those two would later run Disney).

They ended up negotiating with Michael Eisner at Paramount and Frank Wells at Warner (those two would later run Disney).

Eisner believed in the movie and hammered out a deal against all internal criticism. It was a risky bet for the studio.

"Frank was making a deal. Michael was making a movie."

"Frank was making a deal. Michael was making a movie."

The deal shocked the industry. Heads of other studios thought the terms would set a precedent and be bad for the industry.

"A deal that is going to destroy this business."

"A deal that is going to destroy this business."

But Spielberg was eager to prove that he could get a film done efficiently. He ran on a tight schedule, with cheaper special effects and more storyboard planning.

"We didn& #39;t do 30 or 40 takes; usually only four. It was like silent film—shoot only what you need, no waste. Had I had more time and money, it would have turned out a pretentious movie."

Indiana Jones became a blockbuster franchise. And Spielberg further refined his contracts to capture more upside.

For ET, he got a split of the videotape profits: "I saw that video was going to be a very important ancillary market, and in many cases a primary market for film."

For ET, he got a split of the videotape profits: "I saw that video was going to be a very important ancillary market, and in many cases a primary market for film."

Until forming Dreamworks with Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen, he stuck to Ford& #39;s advice: don& #39;t risk your own capital.

He continued directing for gross points and a share of ancillary income like merchandising royalties.

He continued directing for gross points and a share of ancillary income like merchandising royalties.

"I& #39;m a gambler. I haven& #39;t taken a salary for almost a decade now. I love gambling to see what& #39;s going to make it and what& #39;s not."

But he wasn& #39;t really gambling. His bets were de-risked and he worked with other people& #39;s money.

He created call options with potentially large upside and a limited investment of time and reputation.

He created call options with potentially large upside and a limited investment of time and reputation.

"I would love to see people taking more chances. Forgoing all their salaries and not getting money upfront. Taking a piece of the action. Everybody goes out and gambles. And then it becomes kind of like a corporate movie—everyone is a shareholder."

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter