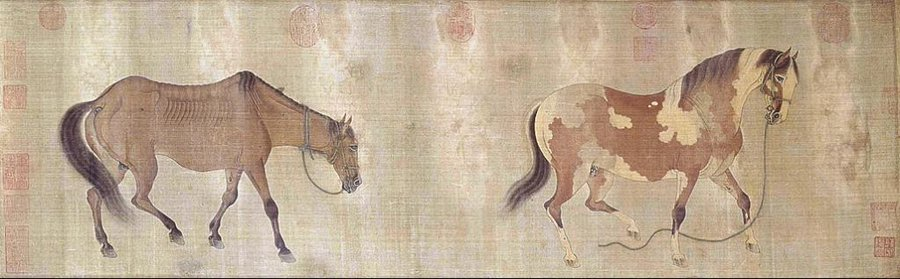

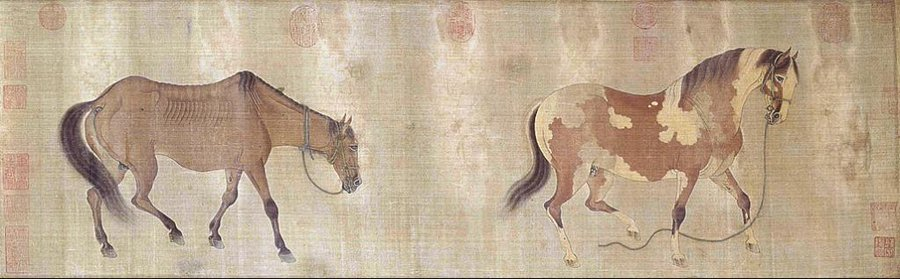

There& #39;s a lovely medieval Chinese painting which excellently demonstrates the intersections between art, text, media, symbolism, politics and expectation. It& #39;s by an artist called Ren Renfa (1254-1327), and is known as Two Horses

(Thread)

(Thread)

Ren was a scholar-elite, one of the traditional Chinese civil servants versed in art and poetry.

The painting, currently at Beijing Palace Museum, is ink on silk. It measures 30x140cm and - as these dimensions suggest - it is a scroll. This is important, as we shall see later.

The painting, currently at Beijing Palace Museum, is ink on silk. It measures 30x140cm and - as these dimensions suggest - it is a scroll. This is important, as we shall see later.

He lived during the Yuan dynasty, the 13th & 14th century period of Mongol rule in China. To a country which prided itself on its culture and civilization, the conquest and subsequent rule by an alien power, seen as barbarian, was deeply traumatic. Cultural lamentations abounded.

So turning to the horses, the imagery is very clear. The painting, from 1280, postdates the conquest of China which was completed in 1279. The horse of today - broken, emaciated, fatigued, bridled - looks mournfully at the free, healthy, proud horse of yesterday.

But wait - this is far from the whole picture.

A number of factors mean we need to radically reassess the meaning of this art, just as its original viewers would have done.

A number of factors mean we need to radically reassess the meaning of this art, just as its original viewers would have done.

First among these is the importance of the political moral philosophy of Confucianism. Confucianism emphasised personal ethics and morality. Loyalty and duty lay at the heart of a number of key vertical relationships: wife-husband, son-father, subject-master.

As well as this intellectual context, this is where the importance of the horses& #39; place on a scroll comes in. A scroll& #39;s owner would unveil it in stages to its viewers. This is not a passive, one-way act but a dynamic, interactive process; it is image as a controlled performance.

This ability to control which parts of the scroll were shown, and when, combines with another feature of Chinese art. Paintings, which were shown in social gatherings, also had textual elaboration, a sort of integrated caption. Ren& #39;s flips the meaning of his work on its head.

“…Some of the scholar-officials of this age are chaste and some are profligate, differing like fat and lean horses. If one remains lean yet fattens the whole nation, he will not be lacking in purity...

...But, on the contrary, if one seeks to fatten only oneself and emaciate the masses, how will he not bequeath a shameful reputation for corruption? So if you judge a horse only by its external appearance, you really will come to feel ashamed…”

(the translation comes from James C. Y. Watt, The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty)

So let& #39;s look at our horses again and re-evaluate. The horses no longer represent – or rather, do not just represent – 2 Chinas. Rather, they represent 2 kinds of official.

So let& #39;s look at our horses again and re-evaluate. The horses no longer represent – or rather, do not just represent – 2 Chinas. Rather, they represent 2 kinds of official.

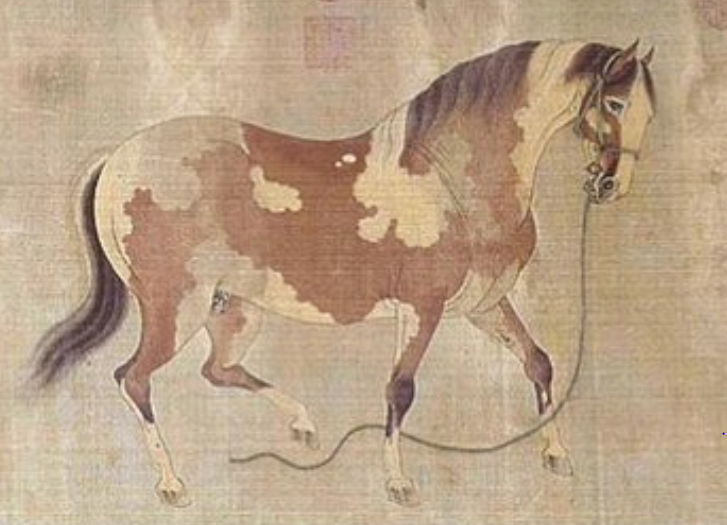

The horse on the right has collaborated with the alien regime. It is fat through greed, successful and untethered through a lack of humility and scruples. The horse on the left is selfless; it is lean, humble, and true to its morals

This art is powerful, political and pedagogic, inspiring an emotional response to current affairs but also prompting introspection and moralistic reflection. Crucial to its message and purpose is the clever, staggered revelation afforded by its nature as a scroll.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter