Protestors fighting for a new balance of power in America are calling for the removal of Confederate monuments. The same monuments were put up by protestors fighting for the same thing - except they were struggling to maintain the power of white Southern elites. (Thread).

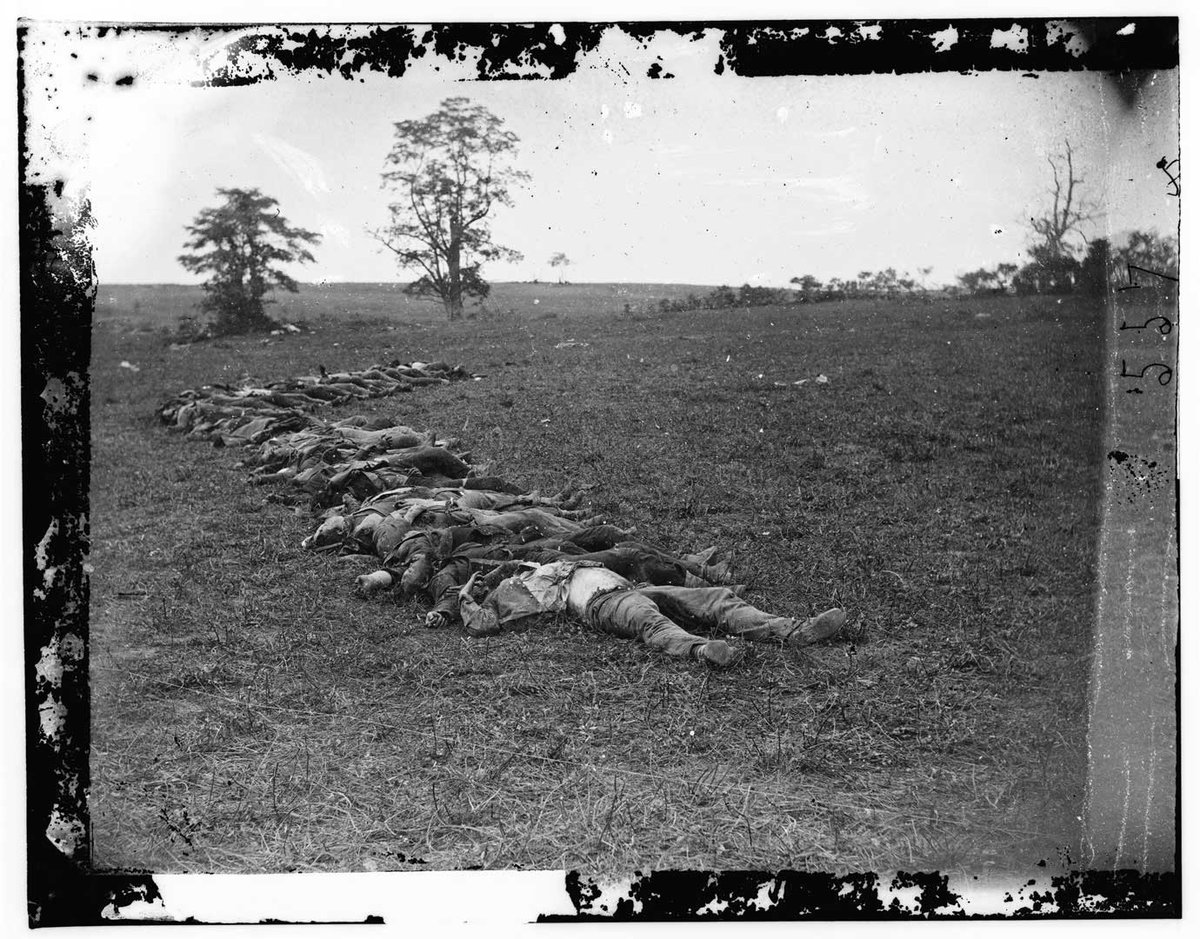

At the close of the Civil War, Union occupation and the collapse of the Confederate currency took political and economic power away from the South’s former elites. They had their land, their history, and not much else.

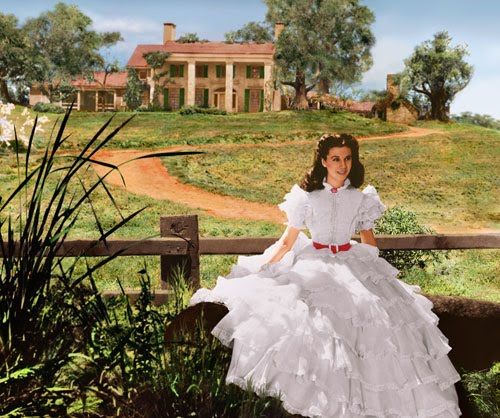

But that was enough to win back their power. How? Southern elites used southern patriotism and white southern womanhood to persuade Southern whites to forget class differences and band together as a “pure white Democracy.” The creation of Confederate monuments played a huge role.

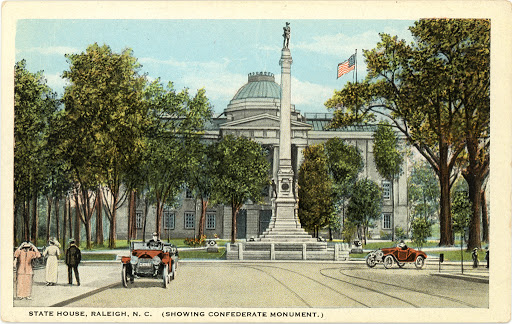

Let’s look at the Confederate monument at North Carolina state capitol. It was the creation of the Ladies’ Memorial Association of Wake County (LMA).

Led by socially prominent Confederate widows, the LMA formed in May 1866 to rebury Confederate dead from makeshift battlefield and hospital cemeteries.

LMA asked the state for $1,500 to finish their cemetery and packed the legislature’s visitor gallery during the vote – the first time white Southern women had appeared in a public, unified protest. They got their money.

Meanwhile, tensions were high in the fight over Black rights. The war had emancipated them, but the South was still resisting granting them the vote. As the LMA prepared to rebury their dead, the Raleigh paper talked of the South’s “political slavery” to the North.

Raleigh& #39;s elite young men carried out the reburials in 1867, much to the distaste of one, who recalled that “the negroes were free and the whites had to work.”

On May 10, 1867, the anniversary of Stonewall Jackson’s death, the LMA organized a procession and ceremonies for the newly completed cemetery. This procession was an act of defiance against the Union occupiers, who had prohibited similar ceremonies elsewhere in the South.

The LMA came into action again in the early 1890s, to agitate for the erection of a state Confederate monument. The timing was no accident. The pre-war elites had regained their power, but what would become known as the Populist Party arouse to challenge them.

In the 1890s, poor Southern whites had a choice: class or race. Would they join with other economically marginalized people to make life fairer for those not born into wealth? Or would they fight with white elites to maintain whatever racial privilege they thought they had?

The LMA sprang into action to raise runs for a grand monument, including persuading some of Raleigh’s leading citizens to put on their old Confederate officer uniforms and reenact a camp scene.

In 1893, the ladies packed the legislature to ask for $10,000 for the monument – filling the galleries, the lobbies, the aisles, and even sitting on the steps of the speaker’s stand. The House approved the funds and ordered the monument be placed on the capital square.

But when the ladies returned in 1895 to ask for a final loan of another $10,000, they faced a new legislature. Black voters and white farmers had united behind a progressive agenda and won power.

The local Populist newspaper urged legislators to spend money on schools instead, writing “It is not at all certain that any monuments ought to be built on either side to perpetuate the memories of our unnatural civil war.”

The ladies’ request for a loan was denied by the NC Senate on February 23, 1895. But a manufactured racist scandal brought the monument back from the dead.

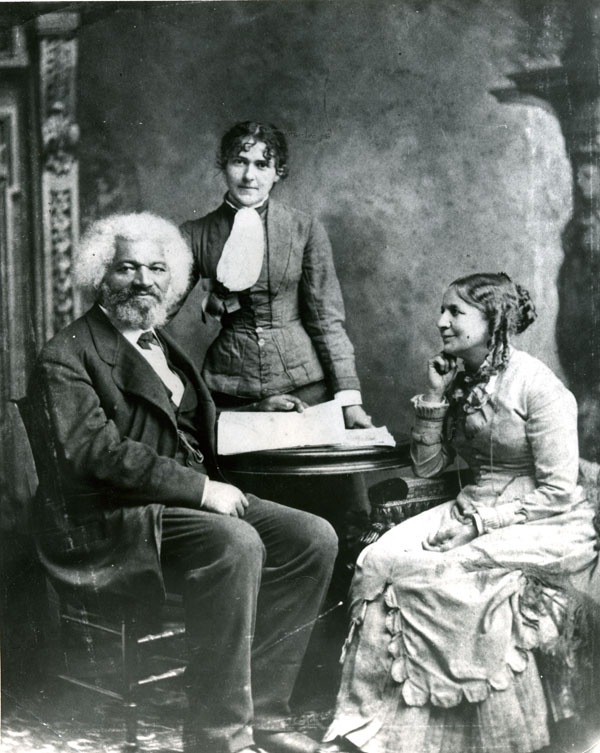

A Black legislator had proposed adjournment in honor of the February 20th death of Frederick Douglass. His resolution was approved. Political opponents pounced. Headlines read “Miscegenation Legislature Adjourns in Loving Memory of Fred Douglass” and “Shame, Shame, Shame.”

The legislators who had voted to approve honoring Douglass, who had married a white woman, were accused of promoting interracial sexual relationships. “All patriotic men must stand together to preserve the Anglo Saxon civilization,” the local paper trumpeted.

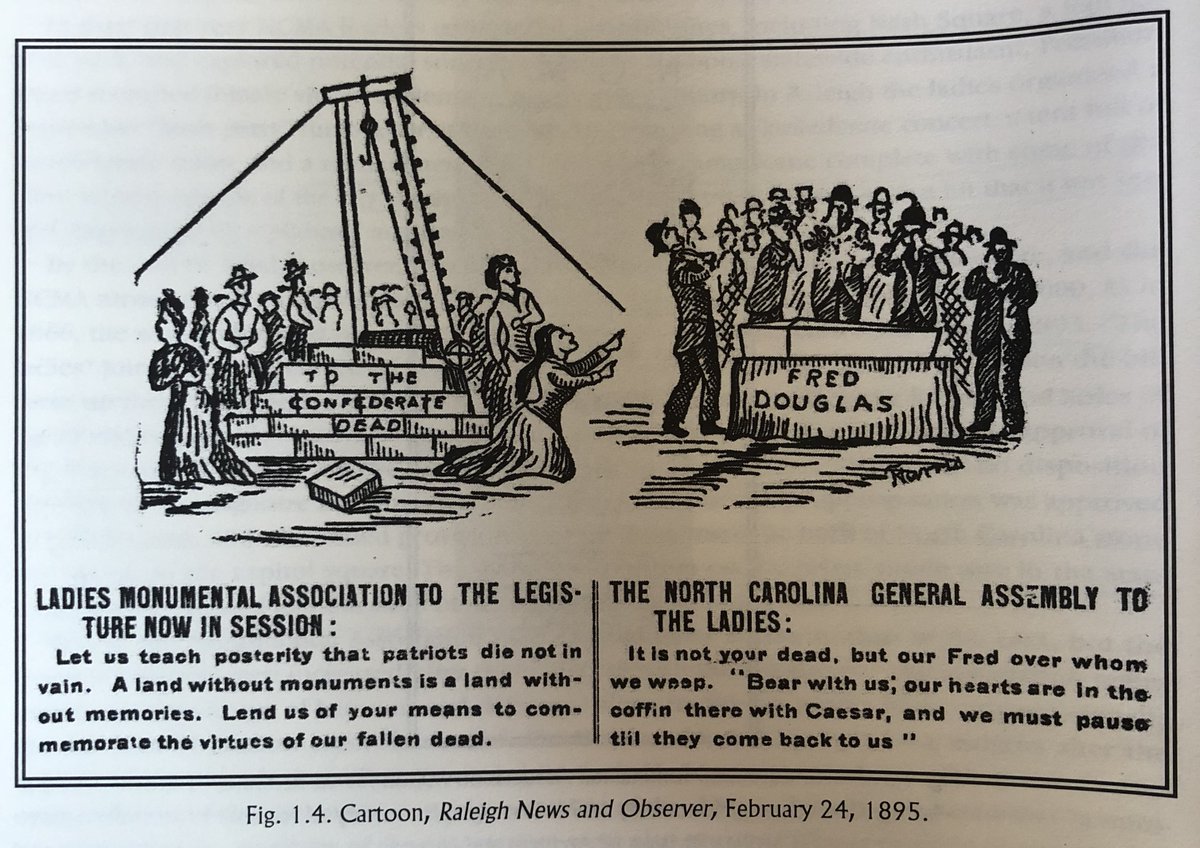

The newspaper linked the honoring of Douglass with the denial of funds for the monument with a editorial cartoon. The ladies plead to commemorate “the virtues of our fallen dead”; the legislators respond “it is not your dead, but our Fred over whom we weep.”

On February 28, a new bill was introduced, proposing to give the LMA $10,000 outright – no longer as a loan. This time, it passed. Sponsoring a Confederate monument was a way for white legislators to signal their racial loyalty was greater than their class interests.

The newspapers reported about the progress of the monument alongside the upcoming election. A few weeks before the monument’s unveiling, the progressive party was defeated. “No Negro Rule in Raleigh,” the city’s paper declared, announcing the triumph of “pure white Democracy.”

On May 20, 1895, Stonewall Jackson’s granddaughter pulled the cord to unveil the 75’ tall granite shaft, watched by his widow and the widows of two other Confederate generals. (They wore black for the rest of their lives, like living monuments to the Confederacy.)

The ladies had said they just wanted to honor the dead. No one wanted to tell them no. But what they were really doing was using the idealized past to fight change in the present. They were elites who fought hard to regain their social and political power.

In June 2020, after demonstrations around the base of the statue, protestors removed two of its smaller figures, handing one from a stoplight and dragging the other outside the courthouse. The governor then ordered the rest of the monument dismantled and put into storage.

The fate of the Raleigh Confederate monument is undecided. As we think about what should happen to it, and to the rest of America& #39;s Confederate monuments, we need to remember that they were always messages about who should be in power and who should remain content to serve.

Sources: this thread draws heavily on Catherine W. Bishir’s fantastic “‘A Strong Force of Ladies’: Women, Politics, and Confederate Associations in Nineteenth-Century Raleigh,” in https://utpress.org/title/monuments-to-the-lost-cause/.">https://utpress.org/title/mon...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter