Tomorrow is the 68th anniversary of the Night of the Murdered Poets—Stalin’s murder of the members of the Jewish Antifascist Committee. These intellectuals played a key role in organizing poltical and material resistance again Hitler, especially among Jews.

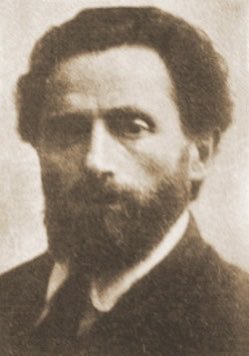

One of the lesser-known victims is Solomon Drizdo aka Lozovskii, who was also the eldest of those killed. He had an extraordinary—and ultimately very sad—life.

A life-long trade unionist, he was arrested for organzing workers and sent to Siberian exile. He escaped in 1908 and fled to Paris, where he organized Yiddish-speaking immigrant workers from Russia.

Affiliated w the Bolsheviks early on, he clashed w their centralist culture. He fought w Lenin, who was hostile to trade unions, and to Lozovskii’s efforts to reconcile warring camps of Russian Marxists. (Lenin always cheered schism.) Lozovskii’s party membership lapsed by 1914.

When the tsarist regime fell in 1917, Lozovskii returned home and rejoined the Bolsheviks. Not because he agreed with their heavy-handed style, but because he believed that they had the best potential to change the lives of millions of workers for the better.

He was one of several Jewish activists (most former Bundists) who convinced the Bolsheviks, who had been quite hostile to Jewish concerns before the revolution, to rethink their Jewish policies.

These activists spearheaded the Yiddish Renaissance for which the Bolsheviks became famous, importing the methods of Yiddish mass agitation and labor orgs they had developed in places like Paris.

But this alliance was always stormy. Days after the Bolshevik seizure of power, Lozovskii publicly denounced the party’s totalitarian tendencies.

But by 1919 he was back. After devastating pogroms in Ukraine, many Jewish activists who mistrusted Lenin’s dictatorial tendencies concluded that the Bolsheviks were the only viable political option. A choice driven by pure trauma.

Lozovskii oversaw international trade union organizations under the Comintern in the 20s, drawing on his earlier emigre experience. Work abroad gave him a modicum of independence.

But once Stalin came to power, he became an uncritical and hard-core Stalinist. Did he conclude that the ends justified the means? Was he driven by fear, a desire for self-preservation, for power? We can’t be sure.

In any case, even his total loyalty couldn’t save his life. He was arrested in 1949, tortured (he was 70) but did not confess or inform on comrades. He was executed on 8/12/52, charged with promoting Jewish nationalism intended to undermine the Soviet Union.

In addressing the tragedy of Soviet crimes, we focus too little on the tragedy of individual lives. Was Lozovskii an accomplice of a murderous regime? Yes. Was he a victim of one? Also yes.

He made numerous choices that were simultaneously right and wrong, ethical and reprehensible: to save Russia’s Jews from muderous pogroms by allying with the Bolsheviks, to resist Hitler by producing Stalinist propaganda.

We’d be better off if we could have more empathy for those forced to make impossible choices.

This week, I’ll be meditating on L’s courage and his determination to bring a better world into being—laudable ambitions, even if they drove him to nefarious ends and self-destruction.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter