Lately I have spoken with several people interested in building systems to help policymakers and practitioners leverage research to improve their decision-making in education. This has made me think a lot about the difference between data and evidence. 1/17

Evidence is data+, meaning data plus analysis methods, research design, assumptions, uncertainty, theory, and expertise. Evidence is expensive, whereas data is not. And evidence is, by design, not available for every question whereas data may be. 2/17

Practitioners want to know which (version of an) intervention will work in their very particular context. But there are infinite versions of these interventions and infinite different contexts. 3/17

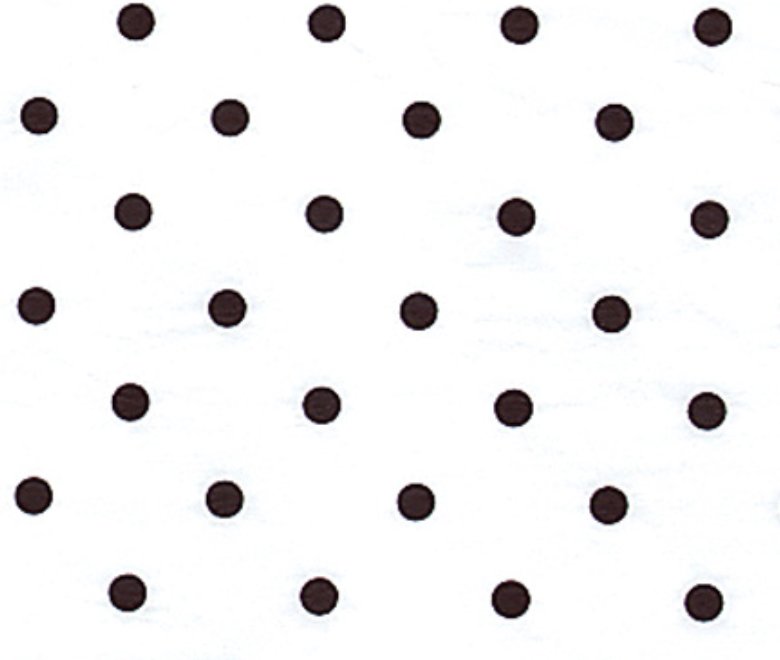

If we were to imagine only two possible variables affecting how well an intervention might work, we’d have a space like this. 4/17

In this space, the dots indicate the evidence from previous studies. The white space includes all the other possible combinations that haven’t been studied. What is clear is that there will always be more white area here than black dots. 5/17

An idea I keep seeing lately is to build systems that include the black dots (evidence) but that also fill in these white areas with *data*. When a practitioner asks “will this intervention work in my context?” the system then locates the “nearest” study. 6/17

But by definition, this nearest study is more likely to be data than evidence. Of course, you might be wondering what’s so wrong with this. Surely some data is better than no data, right? I’m increasingly convinced that this is not the case. 7/17

We know that naive treatment effects in observational studies can be not only biased but *in the opposite direction* of true treatment effects. We know that small studies result in confidence intervals so wide that both negative and positive treatment effects are included. 8/17

And yet, this data provides an estimate of the treatment effect - a number - which now makes the decision seem to be based on research. This carries weight. 9/17

But what, you may ask, is a practitioner to do if instead we didn’t include this data and there was no evidence for this exact intervention in this exact context? Well, they’d have to begin by recognizing this. 10/17

They might then need to look for treatment versions and contexts slightly “nearby” and extrapolating, based both on the treatment effect estimate in that study, the logic model, and the theory. 11/17

Even better, they could look beyond a single study and instead examining a whole class of interventions over different contexts, to see how much this “local” question matters. But this would require extrapolation - there is no way around this. 12/17

I’m ok with this extrapolation - it recognizes the role that evidence plays in decision-making, but also allows for other criteria and information to be taken into account, and for it to be clearly identified as such. 13/17

To be clear, I’m not letting the research community off the hook here. All too often we haven’t mapped the space of potential decisions, intervention, and contextual features. Too often the black dots are all clustered around one another, leaving whole "areas" without evidence.

If we were more thoughtful here, we could reduce the distance between the practitioner’s contexts and questions and the “nearest” studies. 15/17

Overall - if we want to build systems to help people leverage research, then we don’t need more data. We need more evidence - we need more black dots. 16/17

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter