Great question from @PabloVidalRibas on @AcademicChatter

As a legal theorist (I often have to write things out to think them through) with lots of experience in this, I thought I might share a few thoughts

[A Thread on Academic Writing] https://twitter.com/PabloVidalRibas/status/1291023968703582213">https://twitter.com/PabloVida...

As a legal theorist (I often have to write things out to think them through) with lots of experience in this, I thought I might share a few thoughts

[A Thread on Academic Writing] https://twitter.com/PabloVidalRibas/status/1291023968703582213">https://twitter.com/PabloVida...

PART II: The BIG Principles:

1) This genuine & #39;editing& #39; transforms good work into excellent work. Too often we academics write with focus only on the content. Proper editing challenges us to focus on conveying the essential message

1) This genuine & #39;editing& #39; transforms good work into excellent work. Too often we academics write with focus only on the content. Proper editing challenges us to focus on conveying the essential message

(note, this is one of the many benefits of #academictwitter - we have to write concisely ... the pain ... the horror)

2) Good Editing Takes Time: We live in a time-poor profession, with deadlines ever looming. It is hard to make the time to edit properly, which is more likely to take weeks/months than days. Strict requirements like work counts are often the thing that forces us to edit

We need to ensure we build this time into our planning. I expect my (law) PhD students to expect to spend 4-6 months from editing after the 1st complete draft.

We need to bring this discipline to our own writing (I am telling this to myself too...)

We need to bring this discipline to our own writing (I am telling this to myself too...)

3) Good Editing is HARD: Lets not pretend otherwise. Not only do we have to kills cherished sentences, we have to pour over work with which we are already mental & #39;done& #39;. This is not mentally light work, and indeed is often *more* intellectually demanding https://twitter.com/livesinpages/status/1290822997293629442">https://twitter.com/livesinpa...

4) The Shorter Version is Better: The thing is, though, this time and effort is almost always worth it. This is a process of distillation - removing the impurities to leave only the essential material. When done properly, the result is purer, more readable and just ... *better*

5) Excellent Writing Needs Good Editing: Building on the last point - your work will be better if you spend time on refinement than if you aim for & #39;perfection& #39; in the first draft.

I tell my students to write shit first (& quickly) - it& #39;s much better to get words down then refine

I tell my students to write shit first (& quickly) - it& #39;s much better to get words down then refine

6) Editing Demands Focus on the Essentials: This improvement comes because we focus on effectively conveying the read the essence of what we want them to learn. Moreover, we are forced to think about the messaging as well as the message: "do I need this X?" & "is Y clearer"

In short, this process of good editing (often dictated by word counts) needs to be celebrated as an essential part of good academic writing (noting that it is hard, and takes time...)

[Side bar - My experience] Before I get on to concrete tips, let me share my PhD journey.

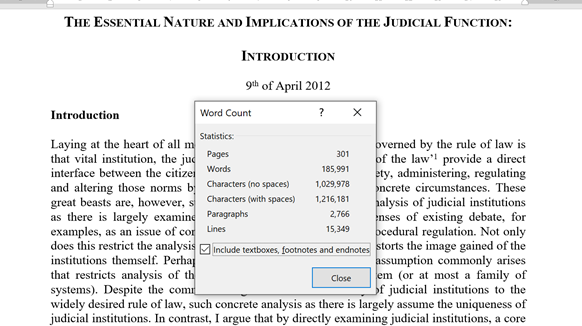

The first draft of my thesis (on judicial theory) was around 240,000 words long. It took me nearly 12mth and 2 more drafts of solid editing to bring it down to 100k words.

(proof of edits)

The first draft of my thesis (on judicial theory) was around 240,000 words long. It took me nearly 12mth and 2 more drafts of solid editing to bring it down to 100k words.

(proof of edits)

I did this without cutting substantive content, but through line by line refinement and multiple iterations. The final work was infinitely better as a result. I picked up a few tips and trick along the way...

Part II: Practical Tips

1) Versions are Great: I find it really works better if you mentally know you are not permanently losing anything (even if in reality you never go back to it). Every time I start a new major edit I would create a new folder, so I can always see earlier

1) Versions are Great: I find it really works better if you mentally know you are not permanently losing anything (even if in reality you never go back to it). Every time I start a new major edit I would create a new folder, so I can always see earlier

2) Have a Plan: Sit down and work out precisely what you need to do. This needs to include critical reflection on your message and messaging, as well as things like work targets.

For my thesis, I knew I would need multiple iterations to get there. I aimed for 30% reduction in 1st -> 2nd draft, and another 30% in 2nd --> 3rd draft. This gave me concrete objectives for each section.

I even got close to my targets! (Second draft here)

I even got close to my targets! (Second draft here)

3) Structure is Key: A good writing depends upon good structure. While line-by-line is useful, your first step in editing needs to be looking at the big picture.

Step back. What are the essential argument? What is the conceptual infrastructure you need to provide?

Step back. What are the essential argument? What is the conceptual infrastructure you need to provide?

The start of a new version is good chance to sit down with a sheet of A3 paper & pen, and map out your arguments and progressions. You can then map back to your current structure and think about where things fit best (or are not necessary). This works for whole piece or parts

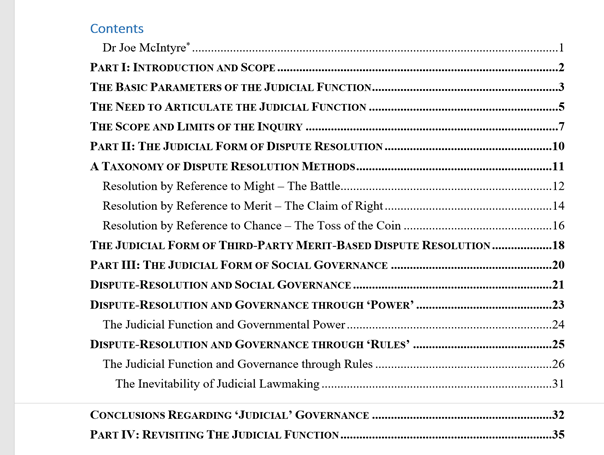

4) Good Headings are Your Friend: I really like the use of headings to flag to the reader where you are going - and as a device for you to think about this too. I use Heading Styles in word, which allow you to auto-populate a ToC.

You should be able to look at each heading and know what the essential point you need to make in that section. What is the 30 word version of each bit? Once you know this you editing becomes much tighter

5) Progress From Broad Picture to Tight Focus: Once you know what the purpose/argument of your paper/chapter is, how that should be established and supported in each section, and what the essential point of each part is, you are in a position to start editing discrete sections

6) Work on Digestible Sections at a Time: Once I am in a position to start the heavy editing, I create new parallel documents to effectively allow me to & #39;zoom& #39; in on the discrete section.

I can then focus on the very specific without worrying about corrupting the broader piece

I can then focus on the very specific without worrying about corrupting the broader piece

For example, working on the & #39;Judicial Function& #39; chapter above, I would have a new draft document that I would populate. I would then copy & #39;Part I& #39; into a new working document to work on. I might then do a separate doc for & #39;parameters& #39; section

These & #39;working documents& #39; are safe spaces - I can cut, move, try new things etc in the knowledge that I have the earlier V higher up the hierarchy. I might be working on *one* paragraph in & #39;working doc 3& #39; - I go through line by line to reduce from 250 to 180 words

I can ask focus concretely on what & #39;work& #39; the paragraph is doing, on whether this mode of expression is the best, whether this sentence is even necessary.

Once I am happy with a bit, I paste it back into the higher hierarchy, until I have a polished Part I in the draft.

Once I am happy with a bit, I paste it back into the higher hierarchy, until I have a polished Part I in the draft.

I can then repeat this process with other Parts in the process, until I have a complete chapter.

Yes this is a labour intensive process.

But it makes a HUGE difference to the quality of the product, and allows you to cut significant words without losing substantive content

Yes this is a labour intensive process.

But it makes a HUGE difference to the quality of the product, and allows you to cut significant words without losing substantive content

7) Rinse and Repeat: Sometimes it will take multiple iterations to get to your final version. I did three very deep structural overview + line-by-line revisions of my thesis to get to from 240k to 100k words. There were another two drafts that were much lighter - spelling/fn etc

8) Don& #39;t Forget to Read for Consistency: One risk of this iterative processes is that you can get so close that you see what you meant, not what is there. It is important to give yourself some distance and then read over to make sure you have created chaos through splicing

Now this was very hard for me, as I have mild dyslexia, but this just meant that I had to find different techniques for that - eg I always do a final read over in hard copy form with pen/highlighter. This transition of medium affects how we read.

I hope this helps those many of you struggling with these issues. It is a really common problem, and we don& #39;t talk about it enough.

Good academic writing is an art form and it takes time and practice (on top of the subject matter expertise)

Thanks and END

Good academic writing is an art form and it takes time and practice (on top of the subject matter expertise)

Thanks and END

PS some great insights here from @kevinjonheller on how to approach the whole writing caper - and the vital reminder that there is no one & #39;right& #39; way of doing this https://twitter.com/kevinjonheller/status/1291215712501915649?s=19">https://twitter.com/kevinjonh...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[Side bar - My experience] Before I get on to concrete tips, let me share my PhD journey.The first draft of my thesis (on judicial theory) was around 240,000 words long. It took me nearly 12mth and 2 more drafts of solid editing to bring it down to 100k words.(proof of edits) [Side bar - My experience] Before I get on to concrete tips, let me share my PhD journey.The first draft of my thesis (on judicial theory) was around 240,000 words long. It took me nearly 12mth and 2 more drafts of solid editing to bring it down to 100k words.(proof of edits)](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EetAEjUU8AAShzM.png)