Does gender equality, beyond its inherent value, cause economic growth?

This is hard to study in cross-country data, but here is a new and smart approach.

A short thread on a new @IMFnews paper by @atabertay @DordevicLj and @Can_Severr —> https://ssrn.com/abstract=3658594">https://ssrn.com/abstract=...

This is hard to study in cross-country data, but here is a new and smart approach.

A short thread on a new @IMFnews paper by @atabertay @DordevicLj and @Can_Severr —> https://ssrn.com/abstract=3658594">https://ssrn.com/abstract=...

Across countries or over time, any positive relationship between gender equality and growth could arise simply because economic growth produces more gender equality.

The authors nicely deploy a powerful identification strategy due to Rajan & @Zingales: https://www.jstor.org/stable/116849 ">https://www.jstor.org/stable/11...

The authors nicely deploy a powerful identification strategy due to Rajan & @Zingales: https://www.jstor.org/stable/116849 ">https://www.jstor.org/stable/11...

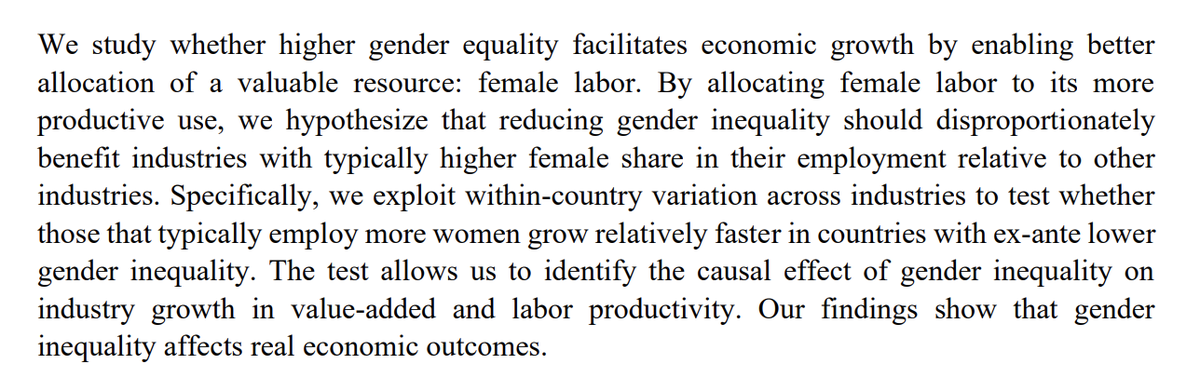

They use *within* country variation in female employment across industries, interacted with across-country (but industry-constant) measures of gender inequality, such as maternal survival and girls& #39; education.

The hypothesis is that if gender equality adds value to an economy, value-added in a *country* with greater gender equality should be relatively higher *for that country* in an *industry* that employs more women.

This smartly controls for the most obvious forms of reverse causality: Growth in a country& #39;s value-added could easily produce e.g. higher girls& #39; education, but it is harder to see how country-relative growth in a *sector& #39;s* value added could shape nationwide girls& #39; education.

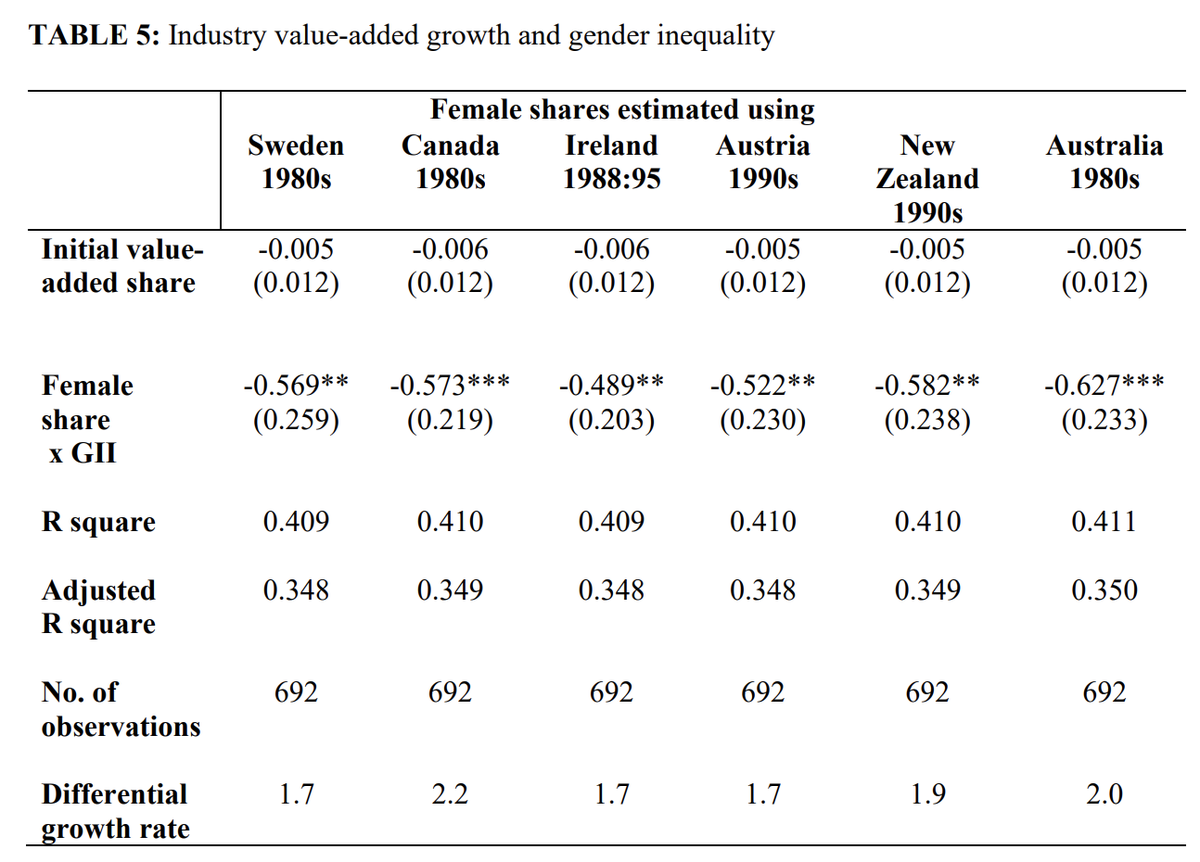

The negative coefficient on the interaction term implies that the relationship between gender *inequality* and sectoral value-added is more negative when that sector employs a greater share of women.

In other words, it is not just that countries with greater gender *inequality* have lower economic performance.

It is that sectors in a country with greater gender *inequality* perform worse when they are relatively more exposed to the limits that inequality places on women& #39;s ability to realize their economic potential, such as by harming their health and education.

There are things left to discuss, of course. Do we believe the Rajan-Zingales assumption that the relevant characteristics of industries are indeed fixed across countries?

Nevertheless this paper is a nice step forward on a very important question.

Nevertheless this paper is a nice step forward on a very important question.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter